ast April, it was not a question of choice for Zomato.

Five months down the line, the food delivery giant got the answer. By September 2020, Zomato had delivered 1.1 million grocery orders across 185 cities, points out CLSA in its brokerage report in April this year. “Thank you for giving us the opportunity to serve you during the lockdown," Zomato wrote in a blog last September, announcing the ‘signing off’ of Zomato Market. With a gradual lifting of the lockdown curbs, the company was getting back to its core business and focus: Food delivery. Though the company flirted with grocery delivery for half a dozen months, there were signs of a promising future.

Back in 2018, Zomato was committing itself a serious relationship by getting into B2B grocery business. It bought Bengaluru-based company WOTU, rebranded it as Hyperpure, and started supplying restaurants everything they needed: Vegetables, fruits, poultry, groceries, spices and dairy beverages. “We are trying to transform Zomato into a foods company, much on the lines of a farm-to-fork model," Deepinder Goyal said in an interview to Forbes India in July 2018. The co-founder explained the evolution of the company. In July 2008, Zomato was born as a food discovery and ratings platform. “In July 2013, we started walking. Now in July [2018] we will start running," he then stressed.

![]()

Three years later, Zomato is sprinting. The Gurugram-headquartered company, which is about to get listed this month, reportedly buys a 9.3 percent stake in online grocery startup Grofers for $100 million. The investment values Grofers at over $1 billion, and gives Zomato—which is reportedly seeking a valuation of $10 billion—a much-stronger blueprint and chance to make a dent in the grocery business. While Zomato declined to comment, Grofers did not reply to a set of questions sent by Forbes India.

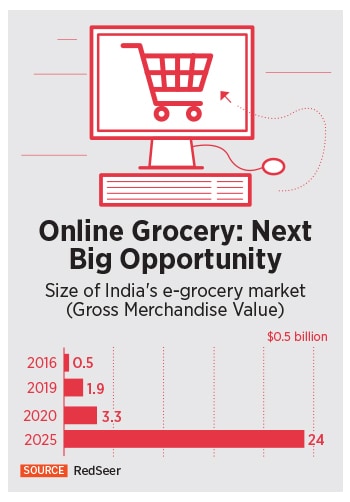

Industry watchers are not surprised with Zomato’s move broadly for two reasons. First, online grocery business has got a massive boost due to the pandemic. From $1.9 billion in GMV (gross merchandise value), the e-grocery market leapfrogged to $3.3 billion last year, according RedSeer. The contribution of fruit, vegetable and staples, the consulting firm pointed out in its report released early this year, stood at a staggering 47 percent. What is interesting, though, is the projection. By 2025, the e-grocery market is estimated to be valued at over $24 billion.

![]()

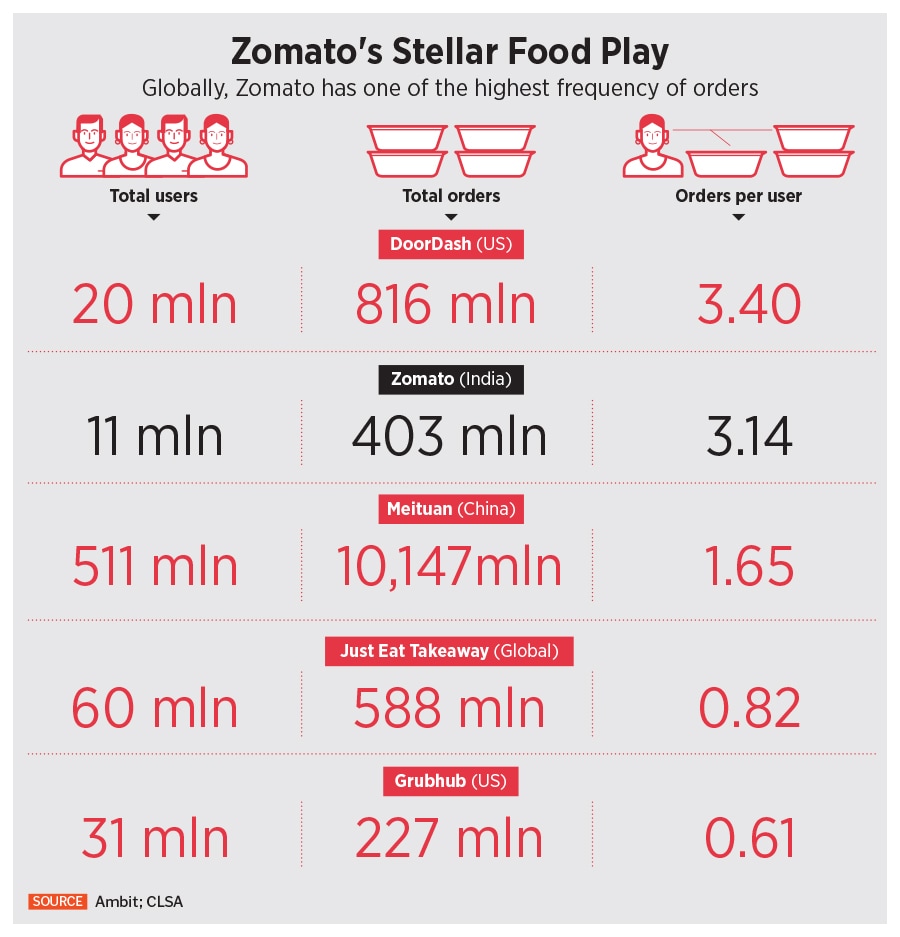

Second, food delivery alone won’t make Zomato a force to reckon with, especially after the listing. It would need more engines, if not one which can be as big and promising as food delivery, to fire. Reason: Low transacting consumers. Though Zomato, Ambit Capital Research points out in its brokerage report in May this year, has a high monthly active user (MAU) base of 42 million, the number for monthly transacting user (MTU) is just 11 million. What this means is that the online food delivery major has to provide more reasons and occasions for consumers to pay. Food alone won’t suffice.

There is another potential blip. The pandemic delivery tailwinds, especially from the latter part of the last year, is likely to abate once the raging pandemic subsides and vast majority of the population gets vaccinated. This, in turn, will not only result in a dip in online food volume and value order, but will also force online food delivery companies to look for new source of revenue.

If food delivery companies needed one more reason to look beyond food, then they must look at the ‘collateral’ damage of the pandemic on the urban population. “The effect of pandemic on lower middle class would be catastrophic," reckons the Ambit Capital Research report.

While 81 million of urban India is poor, a similar number of lower middle class people would be unlikely to afford food delivery services. “Around 150 million urban users are not the right target market for food delivery companies in the near to medium term, the study predicts. If one adds another grim data—women workforce participation in India stands at 20 percent unlike the US and China at 57 percent and 60 percent respectively—the picture becomes clear as to why food delivery companies would not find it easy to expand their catchment area over the next few years. What this means is they need to find other modes to earn income. Grocery might be an option.

![]()

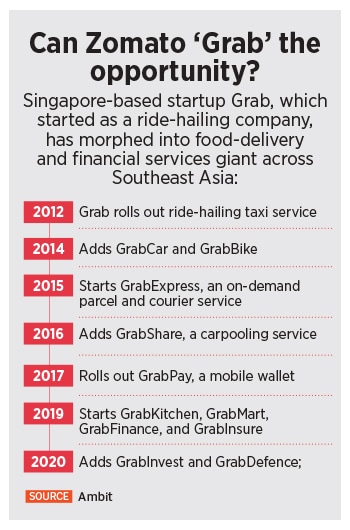

Globally, too, food players are diversifying. In its recent report on online food delivery in India, brokerage company CLSA points out how global players are getting into adjacent categories such as cloud kitchens, grocery and other essential deliveries by using high customer engagement, delivery expertise and data analytics on consumer insights. Online food delivery companies around the world are attempting to transform their single-purpose apps into multi-use ‘super apps’ with a host of convenience services for consumers. “Relatively high take rates in India demand that online food delivery platforms also expand their revenue bases," the CLSA report released in April says.

Zomato, for its part, is well aware of the problem, and the potential solution. One of the threats in the excruciatingly long list of risk factors mentioned in its draft red herring prospectus (DRHP) filed in April includes, “If we are unable to make acquisitions of and invest in complementary businesses, assets and technologies, or successfully integrate them into our business, our business, results of operations, cash flows and financial condition could be adversely affected." Buying a stake in Grofers—which was struggling to raise funds and also dumped its listing plans through SPAC that it was exploring early this year—gives Zomato a fighting chance to keep its growth story intact.

![]()

The going, though, won’t be easy for one simple reason. One plus one doesn’t always make two, reckon retail analysts. Food delivery, they point out, is not equivalent to grocery delivery. The dynamics are different, the market is different. The customer base of Zomato and Grofers, interestingly, is also different. While the former has built its business by having consumers who are ‘convenience’ oriented, the latter has been catering to users who are price sensitive, and would not settle for higher-priced products.

Absence of overlap is crucial because grocery is a high volume and wafer-thin margin business. “Grocery delivery is a very challenging business," says KS Narayanan, a food and beverage expert.

Grocery has been the mainstay of millions of general trade stores dotting streets across the country, where the supply chain is managed in a pretty cost-efficient manner due to lower overheads. “Given tight margins, the prospects of a profitable grocery delivery operation for an aggregator is very low," Narayanan points out.

![]()

Let’s take Grofers, for example. For the FY20 fiscal, total revenue reportedly stood at Rs176.79 crore, and losses were at Rs 637.49 crore. These numbers do not come anywhere close to BigBasket, India’s biggest e-grocery platform: Rs 3,822-crore revenue and Rs 611 crore losses for the same fiscal.

Though the headroom for growth is massive in grocery, one also has to look at the flip side. It is hard to make money and sustain the business. Even BigBasket, a decade-old player and the biggest in India’s e-grocery business, had to sell out recently. In May, Tata Digital bought 64.3 percent stake in BigBasket, reportedly at a post-money valuation of $1.8 billion.

The only thing common between Zomato and e-grocery platforms, says Narayanan, is on-demand delivery. However, with millions of locally-relevant stock-keeping units (SKUs) that are required in the case of grocery, it becomes challenging for an aggregator to stock and deliver.

Another potential impediment for Zomato is the intense fight in the grocery segment. “It has become big boys’ play," says Ankur Bisen, senior vice president (retail & consumer products division) at consulting firm Technopak.

With Tata, Reliance, Amazon and Walmart-owned Flipkart taking deep positions and getting hyper aggressive in the segment, there is not enough room for smaller or niche players. The Zomato-Grofers deal, Bisen points out, is a good example of two desperate players. For Grofers, with an aborted IPO listing plan and its failure to get more funds from its existing or new backers, an investment by Zomato gives it a new lease of life. For Zomato, looking at Grofers gives it an opportunity to take a long-term view. “Will the gambit pay off? It’s too early to say," he says.

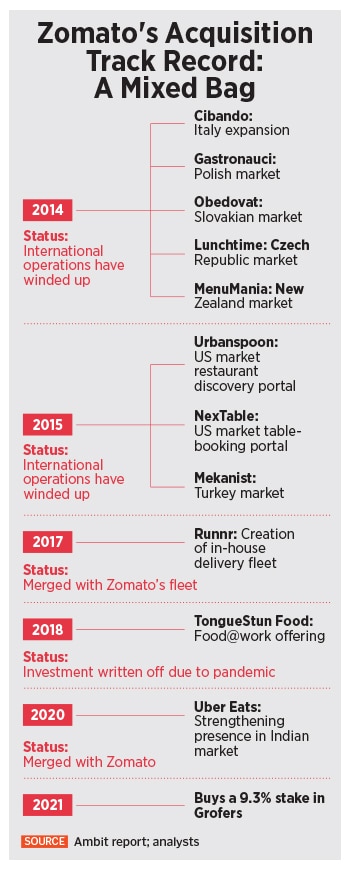

Against the mixed track record of Zomato in its acquisition strategies, Grofers’ deal too does not look too promising. “Zomato has struggled with its acquisitions," points out Ambit in its analyst report. “They tried to expand in multiple geographies but they failed," it adds, listing out prominent examples of large write-offs. The acquisition of Urbanspoon [a US restaurant information and recommendation service] in 2015 for over $50 million and shutting down its operations within five months was a big jolt for the company, the report highlights. Another US-based acquisition in 2015 was written off in 2020.

![]()

Back home, the acquisition of Bengaluru-based Tonguestun Food, an aggregator of caterers and restaurants for office canteens, bombed. Though the plan was to create an entire ecosystem around food, the execution proved to be a challenge. “The pandemic made things worse, and thus another write-off in FY20," the Ambit report points out, adding that the company wrote off its equity investments in multiple global subsidiaries. (See box ‘Zomato’s Acquisition Track Record: A Mixed Bag). With Zomato’s appetite to take risk remaining intact, can grocery change the narrative for India’s biggest online food delivery player?

The answer, perhaps, lies in the draft red herring prospectus (DRHP). “We may not be able to sustain our historical growth rates, and our historical performance may not be indicative of our future growth or financial results," reads the top risk factor outlined by Zomato. Given Goyal’s penchant for taking risk, grocery seems to be the best bet for entrepreneur who has handsomely delivered on the food front.

Deepinder Goyal, founder and CEO of Zomato. Photo by Amit Verma[br]

Deepinder Goyal, founder and CEO of Zomato. Photo by Amit Verma[br]