The IPO routes for India's internet unicorns

Will Sebi's new recommendations make public listings easier for India's internet-based startups?

On February 22, Zomato announced its latest—and potentially last—round of funding of $250 million from five investors, including Tiger Global Management and Kora Management. The online food delivery unicorn is now valued at $5.4 billion, a 1.4x jump from its valuation of $3.9 billion in January 2020, when it raised $660 million. The company is reportedly gearing up for an IPO this June.

“The fundraise adds to the war chest for acquisitions and price wars as the company readies for its initial public offering [IPO],” says Ankur Bansal, co-founder and director at BlackSoil, a credit platform for startups. “It has recently restructured its capital base to create 8.8 billion new shares and tripled its paid-up capital, indicating its intent in the near term.” Plans for the public listing seem to have been advanced due to Zomato’s better-than-expected performance during the Covid-19 pandemic. Zomato, however, reported a 160.6 percent increase in its FY20 losses, to Rs 2,451 crore from Rs 940 crore in FY19, while revenue increased from Rs 1,255 crore in FY19 to Rs 2,485 crore in FY20.

Zomato is part of a crop of internet-based companies, including Flipkart, Nykaa, PolicyBazaar and Paytm, which are planning their IPOs in the coming year or two. According to a report by HSBC Global Research, more than $60 billion has been invested in India’s internet-based startups over the past five years, with around $12 billion in 2020 alone. However, unlike traditional profit-making companies that list on Indian exchanges, these startups continue to be loss-making ventures. The Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi) keeps a close watch on pricing and valuations of IPOs, and the kind of companies coming into the market, with profitability being a key factor. But with the emergence of internet-based ventures over the last 10 years, things are changing.

Pranav Haldea, managing director of Prime Database, says, “These companies, which are funded by private equity [PE] and venture capital [VC] investors, require a huge amount of capital investment before they turn profitable. In line with that, Sebi has been modifying its regulations to encourage such companies to get listed in India.”

Last December, Sebi released a consultation paper on "Review of Framework of Innovators Growth Platform (IGP)", with recommendations from the Primary Market Advisory Committee (PMAC). In 2015, Sebi had introduced a similar segment called Institutional Trading Platform (ITP), but it failed to get any interest from startups. The current reforms in the IGP framework, when implemented, are expected to find far more interest among Indian startups and technology companies.“

“These startups are looking at IPOs to provide exits to their PE and VC investors. Being loss-making, most of these companies would plan to list in overseas markets, given the regulatory environment in India. However, Sebi is trying to get them to list here [through the IGP framework] so that Indian investors can participate as well,” adds Haldea.

Pepperfry, the Mumbai-based online furniture marketplace, is another startup planning its IPO. According to Ambareesh Murty, co-founder and CEO, the company almost broke even last August. With plans to list in the coming 15 to 18 months, it hopes to turn profitable soon. Neelesh Talathi, CFO, Pepperfry, believes the IGP could be a platform for innovative businesses, not just in India but also in South Asia. “This [the IGP framework] is a recognition that the only similarity between all these new businesses is that they"re all dissimilar,” he says. Pepperfry is open to listing on all exchanges, including the IGP, once the new reforms are implemented by Sebi.

IPOs, however, are not always a means to raise money for all companies for some, it is the achievement of a milestone in a company’s journey. At Freshworks, a software-as-a-service (SaaS) unicorn, which has just hit $300 million in annual recurring revenue and is growing at over 40 percent, founder and CEO Girish Mathrubootham has both time and money on his side. “See, we don"t have a definite timeframe,” he says. “But we are a VC-funded company and every VC-funded company knows that at some point, when the timing is right, you have to consider possible options.”

Mathrubootham points out that Freshworks is well-capitalised for now and doesn’t really need to raise more money. “We haven"t even touched the last round of funding… so if you look at the scale and growth, we can be public today,” he adds. But many companies go public much sooner than Freshworks, with $100 million or $200 million in revenues. “We are evaluating all our options. When we decide to go public, it will be a proud moment for all of us as probably the first Indian SaaS company to go public in the US.”

For InMobi Group’s adtech business, which is looking at an IPO this year, group co-founder Piyush Shah says, “You should think about our IPO against the backdrop of US-versus-China. All the large technology-based Chinese companies are not viable options for US investors anymore. For large investors in the US, I keep saying there is no other alternative but to look at India.”

****

Sebi’s recommendations

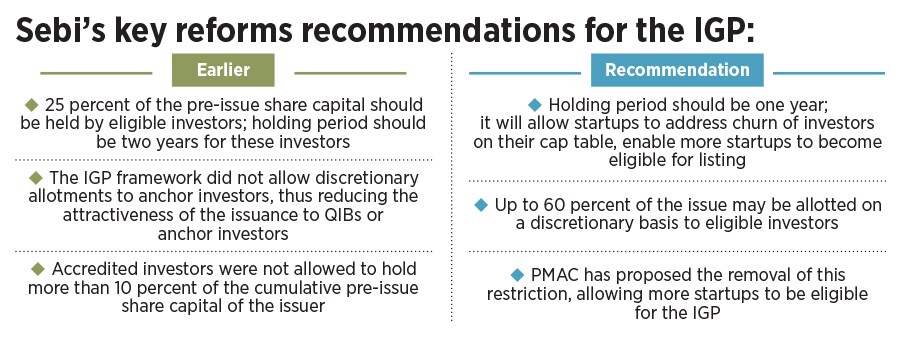

The recommendations that Sebi released last December aim to make the listing of internet-based ventures easier in India, and allow more Indian retail investors to participate in them. (See: Sebi’s key reforms recommendations for the IGP)

Earlier, apart from the requirement of 25 percent of the pre-issue share capital being held by eligible investors, Sebi’s regulations also prescribed a two-year holding period for them. Yogesh Singh, partner and national co-head corporate practice group, Trilegal, explains, “PMAC’s proposed relaxation of the holding period to one year will allow startups to address churn of investors on their cap table, resulting in many more startups becoming eligible for listing.”

Unlike requirements for the main board, earlier the IGP framework did not allow discretionary allotments to anchor investors. “Such restrictions reduced the attractiveness of the issuance to qualified institutional buyers [QIBs] or anchor investors. PMAC has now proposed that up to 60 percent of the issue may be allotted on a discretionary basis to eligible investors.” Singh adds.

Traditionally, Sebi"s Issue of Capital and Disclosure Requirements (ICDR) regulations only permit profit-making companies to list on the stock market. Singh of Trilegal explains, “In the normal course, an Indian listing would have required the issuer to have pre-tax profit of at least Rs 15 crore in three of the past five financial years. Few Indian tech startups have reached this level of maturity, and accordingly public market opportunities were largely inaccessible.” As per ICDR guidelines, Sebi only allows a loss-making entity to go public if 75 percent of its net public offer has been allotted to QIBs, including insurance, mutual fund companies, and alternative investment funds. This means only 25 percent of its net offer is available to investors and high-net worth individuals, therefore raising less funds from retail investors.

The earlier restrictions under the ITP/IGP alternatives, including in relation to issue size, trading lot sizes and eligible investors, did not present a compelling alternative either. “However, reforms proposed by the PMAC last December, if implemented, are likely to address many of the challenges under the IGP framework, and come to the fore as a serious alternative to overseas listing,” Singh adds.

****

Investor & startup sentiments

The IGP framework is likely to benefit startups—both large and small—and is therefore seen as a step in the right direction to change the startup landscape in India. “There is a lot of frenzy around this on both the startups’ and investors’ sides,” says Bansal of BlackSoil. Clearly, the investor appetite for a platform like this is huge, especially since the IGP is advocating for technology and innovation-led companies.

The IGP recommendations include norms for voluntary delisting and migration to the main board, both of which work in favour of startups. However, given that most tech startups are loss-making, how traditional Indian investors will perceive them is yet to be seen. “The mindset of most traditional investors is to check profitability. This will take some time to change. But that doesn"t mean that just because a company is loss-making they shouldn"t be listed,” adds Bansal.

The coronavirus pandemic has helped shift mindsets for a lot of traditional investors. “A lot of them realised the importance of digitisation and automation. When similar [US] companies like DoorDash can go for an IPO, why can"t Indian startups?” says Jatin Desai, managing partner, Inflexor Ventures. “One of the biggest challenges in our startup ecosystem is not enough exits, and they have to happen for the ecosystem to mature. Currently, exits happen when a company gets acquired by a larger global giant, like what happened with Walmart and Flipkart, or when smaller funds exit to larger funds. Secondly, domestic participation for investing in tech startups is low, since most of the large deals includes foreign investors.” For an early-stage investor like Inflexor Ventures, these are the two realistic routes for exits so far the hope is that the IGP or regular IPO would provide a third route.

“Most startups start with money from friends and family, then go on to raise capital from angel investors, then VCs and eventually from PE investors. By the end of this cycle, most of these investors end up holding a significant stake and want to see a return on their investments, which is what an IPO can provide,” says Haldea.

Would startups that are unicorns or bigger, like Paytm or Zomato, want to list on a secondary platform like the IGP? Karan Marwah, partner and head, capital markets advisory, KPMG in India clarifies, “It needs to be kept in mind that the IGP would only be suitable for early-stage startups. Once they achieve scale and higher valuations, they would need to graduate to the main boards.”

Talathi of Pepperfry believes the IGP is essential to encourage an innovative startup ecosystem. “We are wrong if we think of the IGP as a secondary platform it provides more flexibility to younger organisations to list.”

The last date to send public comments on the IGP framework was January 11, 2021, and it is expected to be currently under review, and be implemented soon. Forbes India tried contacting Sebi for a comment on the same, but did not receive any response.

Marwah of KPMG says, “We should consider allowing some exemptions from the additional listing requirements for internet-based startups in a manner similar to the Jobs Act in the US that allows businesses of a certain size significant relaxatioIns from filing and compliance requirements until they attain a certain threshold. This can allow these companies to list and graduate to the more stringent requirements expected of mature public companies in a phased manner.”

****

The lure of the US

According to Tracxn, there are 34 unicorns in India, as on February 4, 2021, including the likes of Glance, Paytm, BigBasket, Zomato, Swiggy, Nykaa and Udaan. Most of these are planning IPOs, regardless of the IGP’s implementation, some in India, but according to experts, most would be considering an overseas listing.

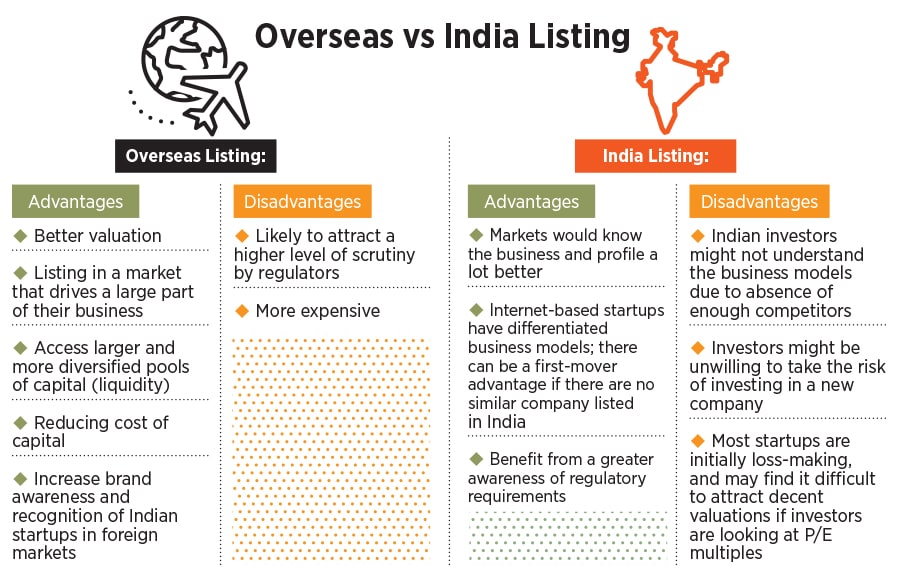

This is due to a number of reasons. R Srikanth, president, corporate finance and investor relations, Infibeam Avenues, which listed on the BSE and NSE in 2016-17, believes the main reason is valuation. “The Indian market is largely dependent on inflows from foreign financial institutions and local domestic financial institutions. In the US, the valuation methodology and metrics are completely different. Therefore, you will find an ocean of difference between overseas valuations, especially in the US, and India valuations.” Like Infibeam Avenues, a number of other internet-based companies such as MakeMyTrip, Bharat Matrimony and Indiamart have been listed. Unlike most others, Infibeam found it a lot easier to list, since, as Srikanth says, “Profit-making is a part of our DNA.”

Companies such as Freshworks and Flipkart are also reportedly planning IPOs in the US. For companies that are either incorporated in the US or have investors there, the option to list overseas seems more beneficial. Additionally, Singh of Trilegal says that tech IPOs that are bigger than a particular size, for instance $6-8 billion, are likely to be listed abroad on account of the depth and liquidity on offer, despite the IGP being implemented. “Overseas investors are perceived to understand technology companies and start-ups better, thus leading to better valuations," says Haldea.

Pepperfry always preferred an India IPO. “Irrespective of the IGP, Pepperfry has always looked at an India listing, since there is a lot of merit in it,” Talathi says. Despite the misbelief around Indian investors not being educated enough, he feels, “The Indian investor is as savvy as an investor outside of India, and is capable and very much willing to understand the business from multiple dimensions.”

According to Marwah, there is also a perception that companies listing overseas will attract a higher level of scrutiny by regulators in those markets, and can prove to be more expensive. “As a business that is so deeply connected with its customers and suppliers in India, I think it is a lot easier to sell your story to people who know you and your business model, than to sell your story to people who have only heard about you,” Talathi adds.

****

The SPAC option

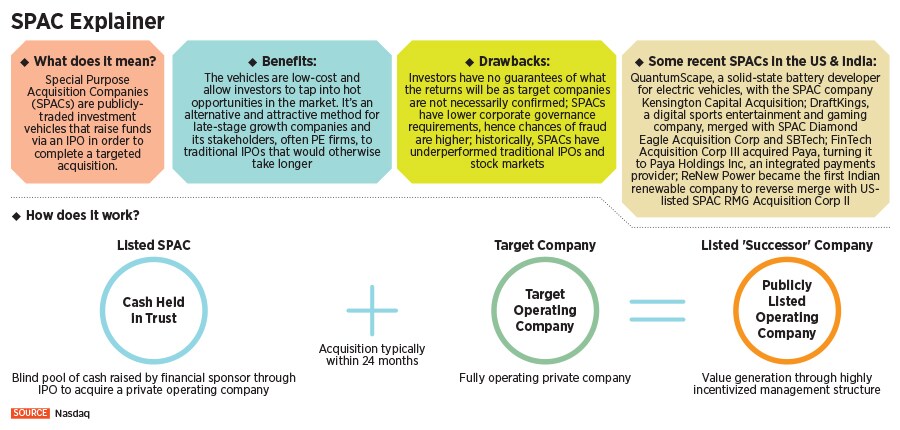

Despite Sebi implementing the IGP framework, companies like Zomato or Paytm, which are eligible to list on the board, are likely to choose an overseas listing, either directly (provided regulations permit) or through the special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) route. “SPAC is a shell company with no commercial operations, which is formed strictly to raise capital through an IPO for the purpose of acquiring or merging an existing unlisted company,” explains Amitabh Malhotra, head investment banking, HSBC India. As per a recent report, online grocery delivery service Grofers is in talks to make its public market debut through a merger with New York-based Cantor Fitzgerald’s SPAC or blank-cheque firm. It is expected to raise between $400 million and $500 million, at a valuation of $1 billion. “We cannot comment on rumours. Our focus continues to remain on growth and building technology that empowers the grocery ecosystem to make products more affordable and accessible for millions of Indian households,” Grofers said in response to queries from Forbes India.

Taking the SPAC route would mean no direct change in Grofers’ business model. However, the infusion of funds is likely to help it scale up and reduce its cash burn. Bansal of BlackSoil says, “The company’s loss has increased by 42 percent in FY20 to about Rs 637 crore, and a SPAC route will make sense for such loss-making startups, as it would be difficult to otherwise raise funds at favourable valuations from retail investors through a traditional IPO in India.”

In 2020, the US saw a frenzy of Nasdaq-listed SPACs, and new SPAC listings continue to pile up in 2021 as well. According to SPAC Research, 160 blank-cheque firms collectively worth $50.2 billion have listed in the US since the beginning of 2021. The trend seems to have grown popular with Indian companies and startups as well. On Wednesday, Goldman Sachs-backed ReNew Power announced it has become the first renewable energy company from India to reverse merge with a US-listed SPAC, RMG Acquisition Corp II, at $4.4 billion post-money valuation, excluding debt. “ReNew will be armed with more than enough capital to fully fund the company"s business plan projections for 2025 and beyond. This means ReNew will not need to raise any additional capital over the intermediate term, unless growth materially exceeds expectations or new business or accretive acquisition opportunities present themselves—of course, both of which would be high-class problems,” said Bob Mancini, CEO and director, RMG II, during an investor call.“

Over the next decade, ReNew plans to maintain its track record of market share growth, and contribution to the greening of the Indian power sector, and to help meet the Indian government’s ambitious renewable energy targets,” says Sumant Sinha, founder, chairman and CEO, ReNew Power. “Over time, we will expand our capabilities even further, with utility-scale battery storage, and customer-focussed intelligent energy solutions.”

A lot of businesses have taken a hit during the Covid-19 pandemic. Malhotra says, “Not everyone could raise more private capital or do an IPO, so SPAC is an avenue for them, should other things fall in place. SPACs have accelerated in this space because they have created an alternative avenue to achieve a lot of those objectives that are probably not being met due to the aftermath of Covid-19, immediately.” Though it might be an attractive method for capital raising for high growth companies, investors committing funds to an SPAC at its IPO have no guarantee of what the returns will be, as target companies are not necessarily identified.

Indian tech startups would prefer foreign SPACs over traditional IPOs for multiple reasons. Firstly, valuation. “A sector-specific acquisition team would value a tech business better than domestic retail investors. Further, SPACs are sponsored by international institutional investors which can provide Indian startups with global recognition and capital access,” says Bansal.

Even though the IGP might make raising SPACs easier in India, the real hurdles according to experts are the tax laws and regulatory compliances. Bansal explains: “As SPACs are essentially shell companies with no operating history, they are not allowed to be listed in India, where there are net worth and track record requirements. Further, SPAC investors should also have tax deferral options, where they are not taxed upon acquisition but at exit, as done for REITs and InvITs.”

Thus, apart from the successful implementation of the IGP, a separate framework must be created for SPACs in India, while protecting retail investors’ interests, much like in the US and other developed markets. Experts are of the view that SPACs might be the more suitable and faster route for the listing of Indian tech startups. “The government must recognise and enable such new structures to propel startups, which are the key to a $5 trillion economy,” says Bansal.

Internet-based startups have enough and more options to list, both in India and overseas. But is this ecosystem likely to be divided between small and mid-sized startups listing via the IGP and larger companies listing overseas via the SPAC route? Only time will tell.

— Additional inputs from Harichandan Arakali and Manu Balachandran

First Published: Mar 02, 2021, 15:30

Subscribe Now