They had heard about Yatri, an app in Kerala, built by Juspay, which allowed drivers to connect directly with passengers, bypassing aggregators. The app that the Karnataka auto drivers got was Namma Yatri, but it turned out to be more than an app. It would go on to change the app-based ride hailing segment in India.

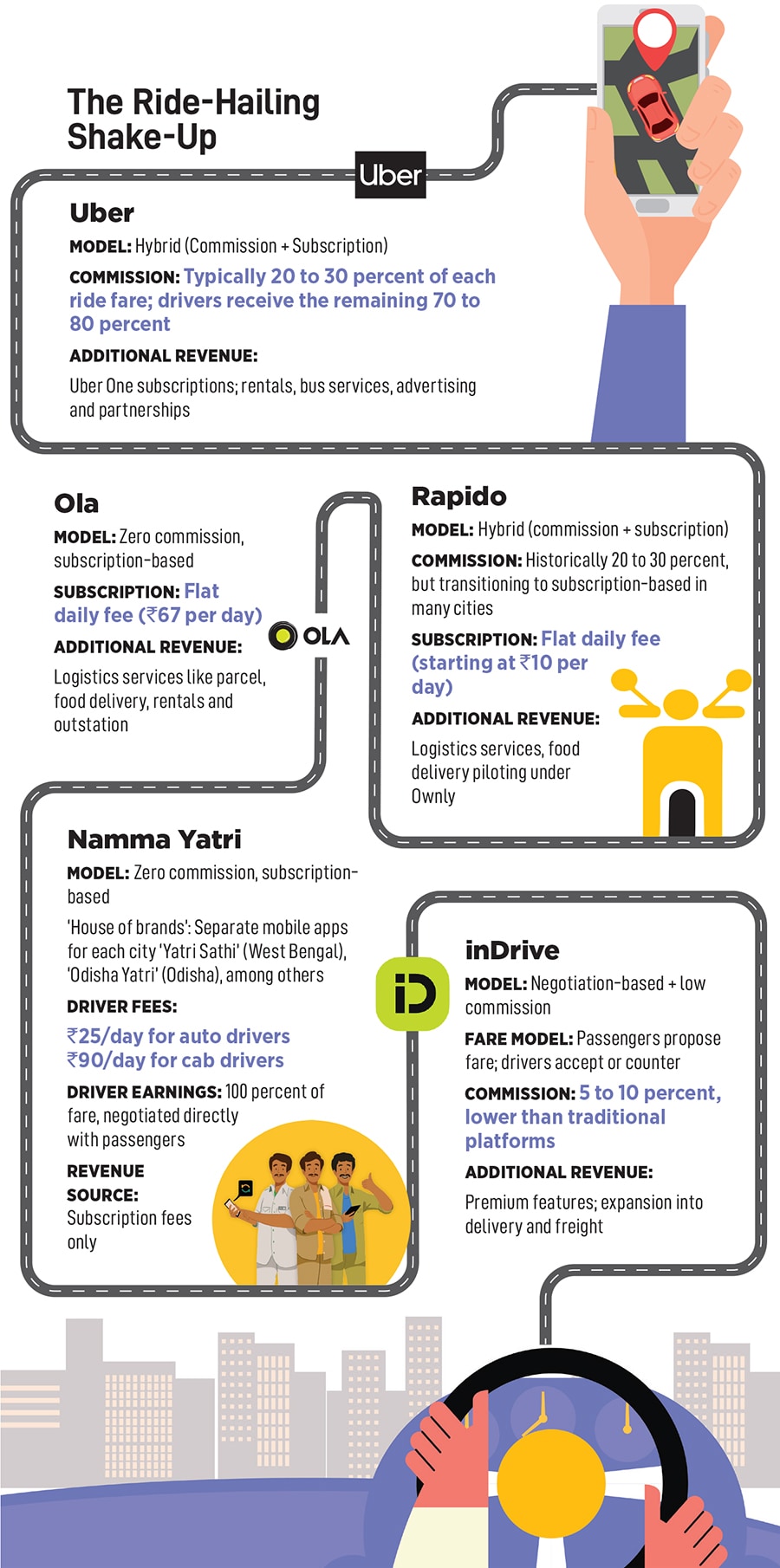

Launched in November 2022, Namma Yatri would require drivers to pay a flat daily fee of ₹25 for autos and ₹90 for cabs. They could keep all of the fares they earned. No commissions. No middlemen. Only subscription.

It was a model born not in a boardroom but on the streets. With zero marketing spend, word spread. Other cities began adopting the model under different names. Yatri Saathi in West Bengal, Odisha Yatri in Odisha, and Kerala Savaari in Kerala.

But the subscription model really tipped when Rapido embraced it.

Initially, Rapido took a stranglehold over the bike-taxi and auto segments using the same commission model that Ola and Uber used. But, as Namma Yatri’s subscription model gathered momentum, Rapido saw an opportunity and began pilots in select cities. The results were immediate: Improved driver satisfaction and better retention.

In 2023, Rapido entered the cab aggregation segment and threw down the gauntlet to Uber and Ola. Embracing the subscription model for drivers, replacing commissions, it has raced to a 14 to 18 percent market share in cabs, says brokerage house Motilal Oswal. Meantime, Uber remains perched at number 1 with a 50 percent market share.

Since the advent of app-based ride hailing in India in 2012, Ola had been number one. It was only in 2023 that Uber overtook it. Now Rapido has dismantled the duopoly.

According to market intelligence firm Sensor, Uber is the largest ride hailing app in India with 33.6 million average monthly active users during the January to October 2024 period, followed by Rapido’s 31.8 million, Ola with 28.6 million, and Namma Yatri with 1.2 million.

But do not count Ola out. It seems to be getting back in the game with a nationwide rollout of its zero-commission model across autos, bikes, and cabs.

Still, one could say that Rapido has dismantled the duopoly.

![]() Bike taxi riders on a hunger strike across Karnataka on June 29, demanding that thegovernment ban on bike taxis be lifted

Bike taxi riders on a hunger strike across Karnataka on June 29, demanding that thegovernment ban on bike taxis be lifted

Commission to subscription

“I would give credit to Namma Yatri. They had been tinkering with that [subscription] model in three-wheelers. We were literally in the process of also understanding how we could disrupt the existing ride sharing model. What Rapido has definitely done is, it has understood this concept to the core and actually implemented it pan India. We did not just implement it pan India, we scaled, because we understood what this meant to the ride sharing ecosystem," says Pavan Guntupalli, co-founder of Rapido.

Founded in 2015, Rapido homed in on the underserved bike taxi segment. Their idea was that “anyone with the intent of earning money, having some free time and access to a bike, should be able to join Rapido," says Guntupalli.

This was also the time when every player was trying to get drivers on a full-time basis. With just $2 million of funding from the likes of AdvantEdge, Astarc Ventures, and Rajan Anandan, among others in its early years, Rapido built a scalable model, by focussing on low-cost operations focussed on bike taxis. But it was only in the last three to four years that it has grown fast: 2.5 times year-on-year, as it fully embraced the subscription model, started to focus on tier 2 and 3 cities, and expanded way beyond bike-taxis into autos, cabs, and logistics.

![]()

“Our market research told us that over the last five years, cab fares had increased by 30 to 35 percent but driver earnings had dropped by close to 40 percent," says Guntupalli. He and his co-founders were clear from the get-go that they will be running a low-margin business. Their target market would always be the masses.

Kunal Khattar, founder of venture capital fund AdvantEgde, who wrote the first investor cheque for Rapido, explains: “Rapido was built with the DNA to deliver a ₹50 product. So, delivering a ₹150 or ₹250 product is easier. It is always easier to go from a small form factor to a large form factor, not the other way around."

Where does that leave Namma Yatri?

Cost advantage

“We still have cost as an advantage, and a lot of learnings—essentially tech which is affordable and scalable," says Magizhan Selvan, CEO and co-founder of Namma Yatri.

The core question the Namma Yatri team set out to answer was: How do you address something as fundamental as quasi-public transport—essential to how cities function—without artificially inflating prices or burning capital?

“Public mobility is a utility, not a luxury," says Karthik Reddy, co-founder and partner at Blume Ventures, which invested in Namma Yatri in 2024. “That’s where Namma Yatri stood out. It leverages the DPI (digital public infrastructure) movement and builds a true marketplace using low-cost, open tech protocols, rather than a managed marketplace."

Beyond popularising subscriptions, Namma Yatri introduced several other innovations which, according to its founders, have made the platform operationally profitable.

“We worked very hard on bringing down the tech cost," says Selvan. “Our goal from the very beginning was to build tech at utility pricing." It helped that the founders of Namma Yatri were also part of the tech team at Juspay and BHIM UPI. In addition to the daily subscription fees for drivers, they introduced a “per trip fee" model, which is ₹3.5 for autos and ₹9 for cabs. Different cities have tweaked this to suit their needs.

Adds Selvan: “We don’t do too much marketing, neither do we offer any discounts to customers."

![]()

New Playbook

As zero-commission and subscription-based models gained momentum, Uber, Ola, and inDrive found themselves at a crossroads.

“India is the third largest market by volume for Uber globally and one of the fastest growing," says Prabhjeet Singh, president of Uber India. Over the past decade, the global ride hailing giant has expanded its offerings in India to include autos, two-wheelers, inter-city travel, and even buses. “However," says Singh, “the reality is that the market is still incredibly under-penetrated, and a lot more needs to get done."

Today, Uber’s fastest growing categories are auto and moto, helping it reach new users who seek cost effective, last-mile connectivity to metro systems. Uber does more trips on two- and three-wheelers in India than on cabs. “This speaks volumes about the scale these segments have already achieved and gives you a clear sense of where the market is heading," says Singh.

While Uber continues to operate on a commission-based model globally, in India it has adopted a subscription-based approach for two- and three-wheelers. “We believe the term ‘zero commission’ does not fully capture the value a platform offers. At Uber, we operate a subscription-based model, where earners pay upfront for access to a set number of trips over a defined period. This effectively results in zero commission per trip, but the service fee is collected in advance," explains Singh.

![]()

Ola recently announced nationwide rollout of its zero-commission model, allowing more than a million drivers to retain all of their fare earnings, whether they drive autos, bikes, or cabs, by paying a fixed fee.

“The launch of the zero percent commission model pan-India marks a fundamental shift in the ride-hailing business," an Ola Consumer spokesperson said. “Removing commissions empowers driver-partners with much more ownership and opportunity. They are the backbone of the mobility ecosystem and giving them complete control of their earnings will help in creating a more resilient and sustainable ride-hailing network across the country."

InDrive has taken a different route. Unlike Uber and Ola, which set fixed prices and automatically assign drivers, inDrive lets riders and drivers negotiate the fare. Users propose a price for their ride, which nearby drivers can accept, counter, or ignore. inDrive provides a recommended fare based on real-time market conditions, which does not surge. Though it has not moved to a subscription model, inDrive says it has the lowest commissions in the industry of 10 to 11 percent in the 13 cities where it operates in India.

“Some companies with deep pockets can afford to run on such [zero commission] models temporarily they invest heavily to grow first and think about profits later. That’s one way to do business, and it’s not necessarily wrong. But our approach is different. We aim to grow the business profitably from the start, without wasting money," says Pratip Mazumdar, country manager and director, India, at inDrive.

Pricing and loyalty

In India’s ride hailing market, customers are not loyal to any one app. For riders, it is simple: They need a cab and do not care which app sends it. For drivers, the app that matters is the one that connects them to a rider quickly and gets them the best fare. There are no Uber drivers or Ola drivers, only drivers using multiple apps and most of them are known to have at least three open at all times.

“In such a market, there are only two ways to stand out," Mazumdar says. “Either you spend heavily to offer deep discounts and subsidies, or you build a platform that is fundamentally different—one that offers unique value to both riders and drivers." InDrive’s fare negotiation, he says, taps into India’s price-sensitive mindset and love for negotiation.

On the other hand, Namma Yatri champions what it calls empathetic pricing. “Rather than the algorithm fully deciding the pricing, can people be involved in deciding the price?" says Shan MS, co-founder, Namma Yatri. The platform anchors its pricing to government-mandated base fares and permits a 10 percent flexibility—usually of ₹10 to ₹20—on either side. Around 85 percent of all Namma Yatri trips require no adjustment to the suggested fare.

To maintain driver loyalty, platforms invest in community and welfare, including insurance, community meet-ups, etc. Based on driver feedback, Uber has introduced trip destination visibility, compensation for long pickups, and performance incentives for high acceptance and low cancellation. It also offers loyalty programmes and diverse digital payment options.

Rapido is working on fuel benefit programmes and other support measures to offset day-to-day expenses. “The goal is simple: Keep adding value," says Guntupalli.

![]() Shan MS (left) and Magizhan Selvan, co-founders, Namma YatriImage: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

Shan MS (left) and Magizhan Selvan, co-founders, Namma YatriImage: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

Hedging of bets

InDrive has been profitable in all its markets. But turning profitable in India is not easy. Says Mazumdar: “In many global markets, like Spain or parts of Latin America, what works in one city often works in another. But in India, things change every 500 km."

This hyperlocal diversity demands localised strategies and city-level operational excellence, often down to the neighborhood. Another difference is the nature of driver onboarding. In Brazil, for example, 80 to 85 percent of driver acquisition happens online. In India, it is the opposite—around 70 to 75 percent is offline. This highlights the need for hands-on training and support.

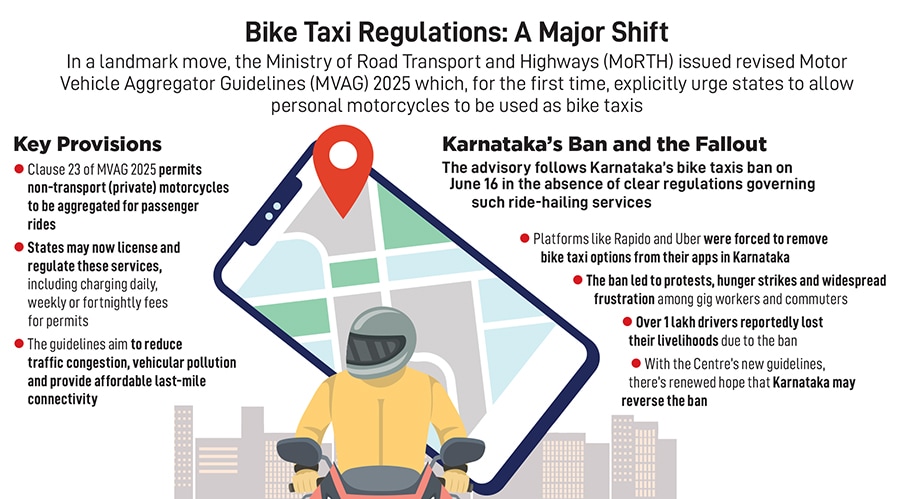

In addition, there are evolving regulations, such as the recent ban on bike taxis in Karnataka and the evolving rules about surge pricing. Under the new Motor Vehicle Aggregator Guidelines (MVAG) 2025, in the cab segment, aggregators like Ola and Uber are now allowed to implement surge pricing up to twice the base fare (as opposed to the earlier 1.5 times) and discounts up to 50 percent during off-peak hours. Drivers must receive at least 80 percent of the fare, unless the aggregator owns the vehicle, in which case the driver’s share drops to 60 percent. Additionally, drivers are entitled to ₹5 lakh in health insurance and ₹10 lakh in term insurance and are free to work across platforms.

Ride-sharing platforms are looking to hedge their bets by diversifying. Rapido, for instance, has partnered with multiple food tech and quick commerce platforms for deliveries. This has been the case for the past six to seven years, says Guntupalli. “For us the key is that the driver should be given whatever opportunities he gets to earn well. So, we are already doing deliveries in partnership with other platforms," he says.

Rapido has introduced ‘Parcel’, a courier service to send up to 10 kg within the city. But the more significant diversification, according to news reports, is Rapido’s entry into the food delivery space under the platform Ownly. “…we are currently piloting a food delivery app in Bengaluru," said a Rapido spokesperson in a statement.

Khattar of AdvantEdge says: “They have studied incumbents, identified gaps, and aim to enter as a third player—not to take 100 percent market share but to capture 5 to 10 percent."

Food delivery isn’t a discovery problem anymore. People order from the same restaurants. The challenge now is delivery efficiency. Rapido has 68 percent market share in two-wheeler taxis. “And 100 percent of food deliveries happen on two-wheelers. They have the highest supply, liquidity, and density—more than Zomato and Swiggy. That’s their moat," adds Khattar.

Globally, inDrive is expanding into new areas. “In some countries we have invested in dark stores and have even explored the idea of entering the grocery segment. While this isn’t something we are pursuing in India just yet, we are actively working on building the product," says Mazumdar. The broader vision is to gradually evolve into a global super app.

But the question remains, when there is a lot more scope for penetration, why this need to diversify? Despite players such as Uber and Ola and others having been around for years, user penetration is still at 19.2 percent in 2025, according to Statista. This is expected to touch 26.3 percent by 2030.

Mazumdar says these are not mutually exclusive. “If you are running a ride hailing business and you have solved the operational challenges, that same model can often be applied to other areas. So, it is not like we are expanding at the expense of our core ride hailing business — it is more an extension of it," he says.

This feels like natural progression and gives drivers more earning opportunities. “Whether you are moving a person or a package, it is still about getting from point A to point B. That’s why it makes sense—and if you look at quick commerce, it’s also a natural extension of logistics," says Mazumdar.

The diversification has not always worked. The Motilal Oswal report has this to say about Ola: “Much of this decline stems from a lack of focus. Ola’s founder, Bhavish Aggarwal, has prioritised side projects like Ola Electric, leaving the core cab business neglected."

Uber tried its hand at food delivery with Uber Eats in early 2020, just before the pandemic, but exited. “That transition helped us refocus on our core strength: Moving people and goods across diverse formats," says Singh. “We believe the ride-hailing market in India is still massively under-penetrated, with huge room for growth."

Uber’s more recent attempts at diversification are in tune with core mobility. For instance, buses, and courier services. It also plans to enter B2B logistics through a partnership with ONDC, where medium and large enterprises can use Uber for last-mile delivery.

Namma Yatri is looking at city services such as parking, public transport and others, which are key parts of mobility. “We have to move 8 billion people. So, taking up more will make us lose focus on mobility," says Shan. Recently, Namma Yatri partnered with the Chennai Unified Metropolitan Transport Authority to pilot Anna Ride Booking, a common mobility app integrating buses, Metro, and autos into a single ticketing system.

New battle lines

“Currently there are 2.5 million cabs that are offline [not on any app]," says Guntupalli of Rapido, adding that every time a driver starts working with a platform such as Rapido, his earnings increase by 25 to 30 percent.

Over the last year and a half, 15 percent of the cabs that joined Rapido have been first-time users of an app, meaning they moved from offline to online. “We want to continue increasing these. In the next five years, we want to try to convert a majority of them to online," says Guntupalli.

Rapido plans to touch 500 cities by the end of the year, up from 250 now, and is also keen on shared mobility.

Singh of Uber agrees that shared mobility will become truly multimodal and deeply integrated. “What began with cars has now expanded to two- and three-wheelers, and we envision a future where platforms like Uber serve as the operating system for daily movement—whether it is a short auto ride, a metro connection, or intercity travel. The goal is to offer a seamless, digital-first experience across all modes, from a single app," he says.

Uber Pool, a carpooling service, was paused during the Covid-19 pandemic. “While we paused it for safety reasons, we have since reintroduced shared mobility through high-capacity vehicles, including 12-, 18-, and 40-seater buses called ‘Uber Shuttle’. These are already live in cities like Delhi and Kolkata," says Singh.

However, the mobility battle is still being fought over only 10 percent of the total commute in a city. “The remaining 90 percent—fixed routes, short commutes, public transport—is largely ignored. If you can solve that cleverly, you are addressing a much bigger opportunity," says Reddy of Blume. “It’s a long game. Nobody has ever built a true mobility marketplace in India." That’s what Namma Yatri is hoping to build.

Gaurav Chhabra, principal, Kearney says the future of urban mobility in India will be: “Greater peer-to-peer features in platforms with more control to drivers and riders in ride selection and fare selection, consolidation of services providers and stabilisation of business model."

We are truly on our way.