Fresh groceries to education and healthcare: The startups catering to Bharat's d

Not every tech-led startup serves up organic food in eight minutes. Some choose the rough-and-tumble of country roads. And they are raising funds and earning revenues

About 110 km from Tiruchirappalli, in Tamil Nadu, lies Vadaku Kodivayal. It is a tiny village, home to 183 residents. It has no digital footprint. You will not find it on Google Maps.

Every morning, at 5:40, Vadaku Kodivayal’s sleepy lanes come alive as a man in a bright green T-shirt navigates his electric three-wheeler cart through them. A melodic jingle drifts from the cart’s loudspeakers, announcing the arrival of fresh groceries and daily essentials.

Nicknamed WoW—short for Wheelocity on Wheels—this cart is from Chennai-based Wheelocity, a startup using technology, electric vehicles (EV), and gig workers for last-mile delivery of fresh food and essential services in rural India. It began its journey by streamlining fresh food supply chains across urban India. But towards the end of 2023, the founders realised that though urban operations offered scale and efficiency, a greater impact could be created outside the big cities.

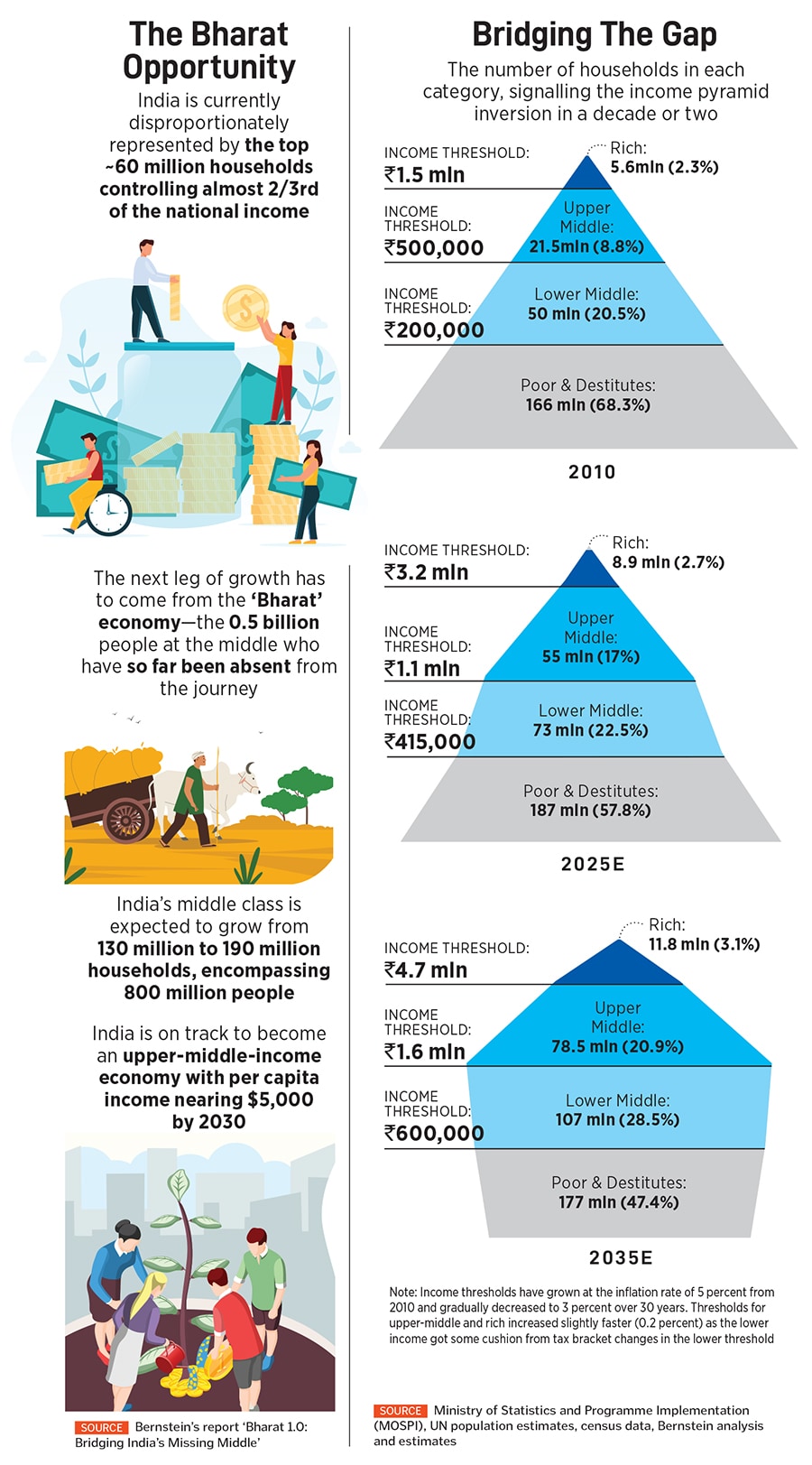

Wheelocity is one among a bunch of startups which has turned their backs on the hustle of big cities and taken the road less travelled. CureBay uses technology and asset-light e-clinics to for health care in underserved areas. Arivihan uses artificial intelligence (AI) to deliver personalised, multilingual and affordable education. SolarSquare makes solar energy accessible to middle class households in Tier II and III towns. CityMall leverages microentrepreneurs for hyperlocal ecommerce delivery. SumoSave offers wholesale groceries with sustainable packaging at affordable prices. And MagicPin digitises offline retail, connecting local merchants to nearby consumers through its hyperlocal platform.

Together, they could be scripting India’s next big consumption story—in the vast, underserved middle of the pyramid—stepping in to fill the gaps left by traditional players. Fuelling this consumption story is that small towns and villages, contract to popular belief, do have disposable income, along with the newly created digital infrastructure.

“The issue is that these markets are extremely access-deprived. We [those living in urban areas] are extremely spoilt. We get annoyed when we don’t get our deliveries in seven minutes. But these markets have to wait for seven days to go to a local haat and buy things," says Selvam VMS, co-founder and CEO of Wheelocity.

Anshoo Sharma, co-founder, MagicPinImage: Amit Verma

Anshoo Sharma, co-founder, MagicPinImage: Amit Verma

This is not the first wave of startups trying to build businesses that cater to what is usually called Bharat. But not many have succeeded so far. Selvam believes most founders design products for urban India and expect Bharat to simply download and use them. “The problem has never been on the demand side—it has always been on the supply side. As founders and product builders, we have failed this market," he says.

Building for Bharat comes with hurdles. Supply chain infrastructure is weak, demand is scattered and logistics are poor. Customer acquisition is not easy, either, because many people are not active on digital platforms and even if they are, expecting them to navigate complex app flows like urban users is unrealistic.

“Partial solutions don’t work for Bharat consumers. They want end-to-end services without having to make complex decisions or manage multiple vendors. For Bharat, models that do part of the job are not good enough. You have to do the full job," says Rahul Taneja, partner at venture capital firm Lightspeed.

Rural markets are highly diverse, requiring hyper-localised strategies and flexible product designs—what Selvam calls “an amoeba approach to product building".

This is why Wheelocity chose to take the ‘phygital’ approach—building a modern-day, tech-enabled ‘thelawala’ (Hindi for costermonger). Its fleet of more than 2,000 electric three-wheelers services 3,500 villages in Tamil Nadu, twice a day, delivering groceries, fresh produce, FMCG and apparel. Each vehicle in its fleet has Internet of Things-enabled weighing plates.

“The exact weight is captured digitally via the gig worker’s app, down to the last decimal," explains Selvam. This eliminates manual errors and prevents the typical 8 percent margin erosion seen in fresh produce. “Atomic innovations like these swung my profit and loss statement by 9.5 percent," he adds.

Mohit Kampani, founder & CEO, SumoSave RetailImage: Subrata Biswas for Forbes India

Mohit Kampani, founder & CEO, SumoSave RetailImage: Subrata Biswas for Forbes India

So far the majority of health care investments has gone into the top cities. “A majority of the population continues to rely on public infrastructure. Though they can afford it, they live in the emerging India, or Bharat, and have no access," explains Priyadarshi Mohapatra, founder and CEO, CureBay. As you move down the tiers, especially to Primary Health Centres (PHCs), the absence of doctors becomes stark. Nearly 70 percent of PHCs lack medical personnel, not due to lack of intent but due to a massive shortage.

When Mohapatra started mapping the patient journey, he realised that the supply chain was broken. Since people do not find doctors at PHCs, he explains, “they turn to local pharmacies, which are often run by traders rather than certified pharmacists. These outlets frequently dispense antibiotics without prescriptions, leading to widespread misuse and growing antibiotic resistance in rural India".

He discovered that cost was not the primary barrier to accessing district-level care, experience was. Patients and caregivers would travel far and often face exploitation by informal health care agents (commonly known as health care dalals, or middlemen) who intercept them at transport hubs and in hospital corridors, redirecting them to private setups with whom they have financial arrangements.

CureBay was built as a hybrid health care model with two distinct components. The first, the tech platform, “was the easy part", says Mohapatra. The real challenge was bringing quality health care to remote and underserved areas.

“We set up a network of asset-light e-clinics, each around 200 to 250 sq ft, staffed by a pharmacist and a nurse," he adds. These clinics are equipped with three key tools: Access to CureBay’s platform, medical-grade point-of-care devices for capturing vitals, and diagnostic tools for common tests such as haemoglobin, sugar, malaria and more.

When a patient arrives at an e-clinic, the staff records their symptoms and vitals, creating a digital pre-clinical note. This is followed by a doctor consultation, which is mostly digital but occasionally in-person. “We call these ‘assisted digital consultations’, a model that blends technology, touch and trust to deliver high-quality care at the last mile," says Mohapatra.

Using the e-prescription given by the doctor, a nurse or pharmacist helps the patient with the medicines and the diagnostics tests, either in-house or through a partner lab. “In this manner, almost 70 to 80 percent of a patient’s health care needs are taken care of, and only at ₹100 for the first-time consultation for the general physician," he adds. Currently, a ₹100-crore company, CureBay has served close to 18 million people so far and has 150 clinics between Odisha and Chhattisgarh.

In certain cases, if there is specialist or tertiary care required, CureBay helps schedule appointments with its partner hospitals. “This removes the health care dalals and information gaps," says Mohapatra.

Priyadarshi Mohapatra, founder and CEO, CureBay

Priyadarshi Mohapatra, founder and CEO, CureBay

CureBay has taken onboard retired and former government doctors, many of whom operate from their homes and occasionally travel to nearby clinics. “This approach helped us bridge language barriers, as both doctors and clinic staff are recruited locally and speak regional dialects," says Mohapatra.

On the tech front, CureBay has built vernacular capabilities, including a large language model (LLM) which supports Odia. A similar model will be deployed in other regions.

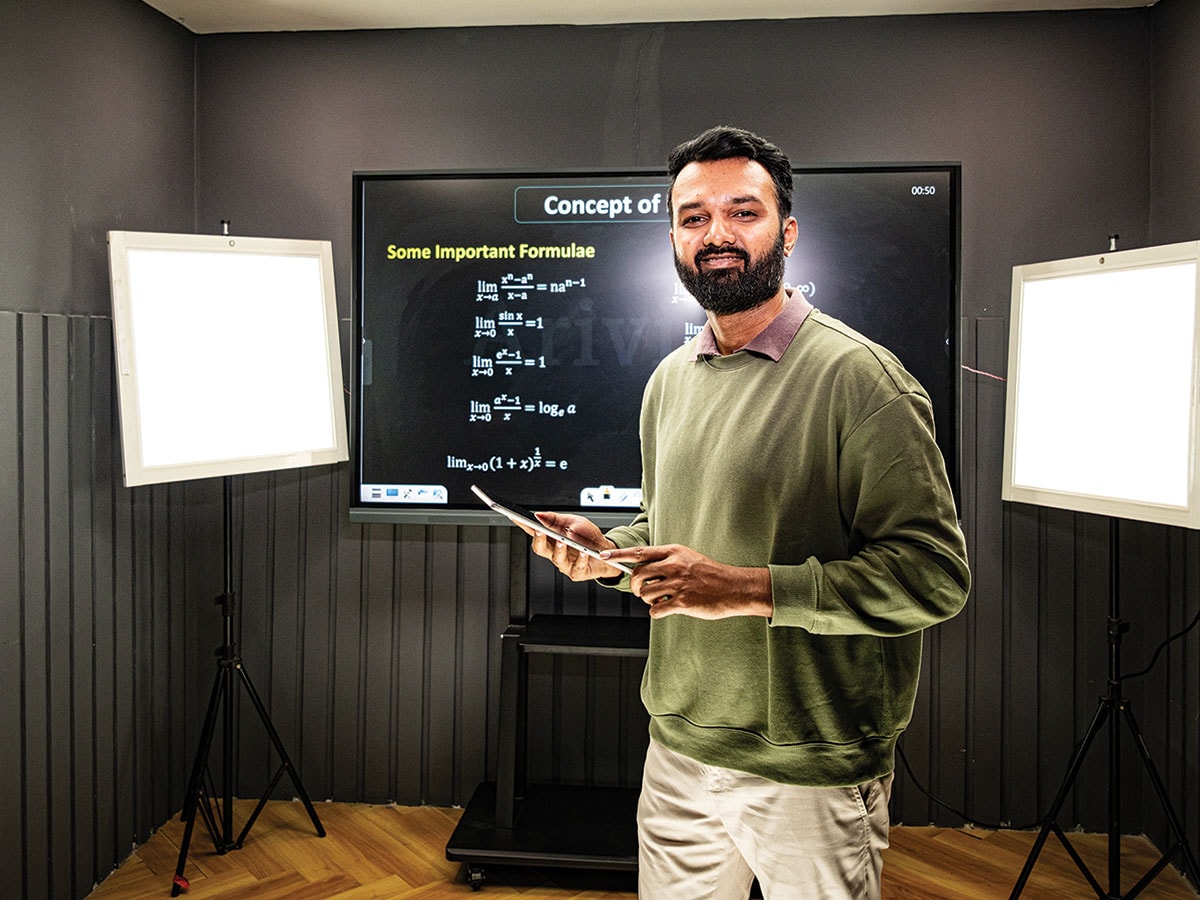

This emphasis on language, accessibility and contextual relevance is equally critical in education. While online education was growing, most platforms either lacked quality or engagement. “Offline coaching centres are the best preparation option for most students, but they are very expensive and, therefore, inaccessible to most," says Ritesh Singh, who, along with Sonu Kumar Prashant and Rushabh Kothari, set up Arivihan to provide students in Tier III and IV cities with affordable interactive education in regional languages.

But finding qualified tutors for every regional language was not easy. So the founding team built Arivihan as an AI-led edtech platform. “These are AI-based interactive lectures from experienced faculty that are personalised for each student. Additionally, students can ask queries through our built-in tutor bot for instant solutions, not just in text, but also in the video format," says Singh. The team has built the entire platform in English and Hindi and is set to go live with Bengali.

“Regional languages are a big challenge, which we believe can only be solved using AI, at scale," he adds. Currently, the platform is live in Tier III and IV cities in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, focusing on imparting coaching for Grade 12 state board and NEET examination preparation. “Most offline classes would cost upwards of ₹20,000, whereas we charge ₹3,000 only for the entire programme, for all subjects. It is a freemium model, where a few chapters are free for students to experience and the rest is paid content," says Singh.

Despite its low rates, Arivihan says it is on the path to profitability, thanks to its AI-led model, which significantly reduces operational costs. The Accel-backed startup sold around 15,000 subscriptions in the last academic year, and clocked a turnover of ₹3.2 crore. With a fresh round of funding of $4.17 million in July, Arivihan hopes to scale up the business a lot faster by moving into more states and languages. “The product building part is done, now it is all about execution," Singh says.

Shreya Mishra, co-founder, SolarSquare EnergyImage: Bajirao Pawar for Forbes India

Shreya Mishra, co-founder, SolarSquare EnergyImage: Bajirao Pawar for Forbes India

The Bharat consumers’ mindset is at the heart of India’s solar adoption story.

The starting investment for installing a solar panel for a 2 BHK is ₹2 lakh. For smaller households, the investment remains in the ₹2 lakh to ₹3 lakh range. But for larger houses it can go up to ₹4 lakh to ₹5 lakh or more.

“What is fascinating is that 70 percent of our consumers are two-wheeler households. They don’t yet own a car. At this price point [of solar panels], they could easily buy a second-hand car," says Shreya Mishra, co-founder, SolarSquare Energy, which with ₹350 crore in FY24 revenue, has raised over $53 million in funding.

Interestingly, 60 percent of its customers do not have an air conditioner (AC). For many, the trigger to go solar is the rising temperatures, especially during the exam season for children. They want to buy an AC but before that they choose to install solar. “An AC can increase the electricity bill by ₹10,000 to ₹20,000 annually. This reflects a very Indian value system: Savings and financial prudence come first," Mishra says.

SolarSquare offers a zero-investment financial product. “It is a five-year loan where the EMI is matched to the customer’s existing electricity bill. For example, if a household typically pays ₹3,000 a month for electricity, they can opt to pay a ₹3,000 EMI instead—for just five years," says Mishra. “Since this amount is budgeted in their monthly expenses, there’s no additional financial strain on the family."

After five years, the loan is paid off and the solar system continues to generate electricity for the next 20. Sixty percent of SolarSquare’s customers prefer taking a loan.

CityMall co-founders (from left): Naisheel Verdhan, Angad Vinod Kikla and Rahul Gill at their warehouse in Khandsa village, Gurugram, HaryanaImage: Madhu Kapparath

CityMall co-founders (from left): Naisheel Verdhan, Angad Vinod Kikla and Rahul Gill at their warehouse in Khandsa village, Gurugram, HaryanaImage: Madhu Kapparath

Outside the big cities, community connections and word-of-mouth matter more. “Everyone knows everyone in smaller towns. Our referral programme gets us close to a third of our revenue. Interestingly, referrals barely work in the metros," says Mishra.

Most startups looking to scale in Tier III and IV cities work closely with microentrepreneurs—individuals who run small-scale, often informal or semi-formal businesses, typically within their local communities. SolarSquare also works with local ambassadors such as hardware shop owners who can tap into these trust networks and make a commission on every order.

Similarly, Gurugram-based CityMall has been working closely with microentrepreneurs. Earlier, it engaged with them to bridge the trust gap in ecommerce, but now has them for last-mile fulfilment. “They offer low-cost, hyperlocal delivery. Without them, building our own delivery infrastructure would be expensive and inefficient," says Angad Kikla, co-founder, CityMall.

The company pays these microentrepreneurs (delivery partners) a commission for every delivery. “We deliver products to them in bulk. They do the bulk breaking, packing and delivering," says Kikla. These are micro-dark stores, but CityMall does not invest in the real estate or manpower. “We are a next-day delivery model, significantly cheaper than quick commerce or kirana stores," adds Kikla. Having a 100-percent online and comparatively asset-light model, he says, “We are making money on every order, unlike most others in this category." It does not charge any platform or convenience fee.

CityMall operates in 60 cities across Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and parts of the National Capital Region. Backed by Accel, Elevation Capital and General Catalyst, it claims to have grown more than three times in 15 months and is doubling its revenue year-on-year. In FY24, it clocked ₹427 crore in revenue.

Ritesh Singh, co-founder, Arivihan

Ritesh Singh, co-founder, Arivihan

Consumer demand in India is deeply fragmented even within short distances. For instance, in Kolkata, Doctor’s Choice is a popular mustard oil brand. But 40 kilometres away, in the Hooghly belt, Saloni dominates. This fragmentation applies to all categories.

MagicPin, a hyperlocal commerce platform, has built its model around this reality. “Retail in India is a trillion dollar market, and 90 percent of consumption still happens offline," says Anshoo Sharma, co-founder of MagicPin. “Our job is to bring these local markets alive on the user’s smartphone."

From small food joints to fashion outlets, MagicPin connects local merchants to digital consumers, enabling discovery, transactions, and even delivery—all within a few kilometers. “We are not competing with the small retailer, we’re helping them stand out," Sharma adds, “hence building on the concept of for Bharat, by Bharat."

From small food joints to fashion outlets, MagicPin connects local merchants to digital consumers, enabling discovery, transactions, and even delivery—all within a few kilometers. “We are not competing with the small retailer, we’re helping them stand out," Sharma adds, “hence building on the concept of for Bharat, by Bharat."

So far, organised retail has largely focussed on the top 40 cities, serving around 200 million consumers. But to unlock the next wave of growth, businesses must reach the next 200 million consumers—spread across 900 to 1,000 cities, says Mohit Kampani, founder & chief executive officer, SumoSave Retail.

A Bernstein report forecasts that while the top 10 cities will contribute $46 billion in incremental retail growth over the next decade, the next 30 cities alone will contribute $170 billion, presenting a much larger opportunity. “This group will be the fulcrum of India’s economic growth. Serving them will require a complete rethink of distribution strategies—more decentralised, more localised, and far more complex," explains Kampani.

SumoSave is building a retail model for middle-income consumers. “We think of ourselves as a modern ration ki dukaan," he says. The stores come in two formats—5,000 sq ft and 2,000 sq ft—and are positioned as full-fledged supermarkets, based in dense middle-income localities.

Their communication is in regional languages and there is no visual merchandising or complex promotional messaging. “We never say 25 percent off—instead, we write the discounted price, and keep pricing simple and transparent, with no complex cashbacks," says Kampani, who often prefers local brands to national brands.

Will quick commerce find its way to Bharat? Kampani thinks not. “Our busiest shopping hours are between 7 pm and 10 pm, with 50 percent of daily sales happening during this window," he says.

Despite the rise of digital payments, 60 percent of SumoSave’s transactions are still in cash. These consumers use digitisation selectively their core financial behaviour remains cash-driven. “That’s how they earn, budget and manage household expenses. It is a different world," says Kampani.

First Published: Aug 01, 2025, 14:28

Subscribe Now