Tewari had grappled with other, bigger problems before. In 2007, when he founded InMobi to change the way mobile advertising was done, there was no concept of a startup or a founder, leave alone funding. People thought he was crazy for giving up a career as a business analyst in the US to move to India and start his own company.

He managed to manoeuvre around the mindset and the misgivings, but the marriage market conundrum stumped him. “They could not get married," recalls Tewari. “When they said they worked at a startup, no one wanted to marry them."

That came in the way of hiring and retaining good people. So, Tewari did what well-meaning people do when they are not quite sure what to do. He called a press conference—InMobi’s first. Indeed, the intention was to find coverage in the media, but the end goal was to make the company credible and, in turn, present its employees as bankable marriage prospects.

Something must have worked. In 2011, InMobi became India’s first unicorn—a privately owned startup valued at more than $1 billion—at a time the term unicorn had yet to enter popular parlance in India.

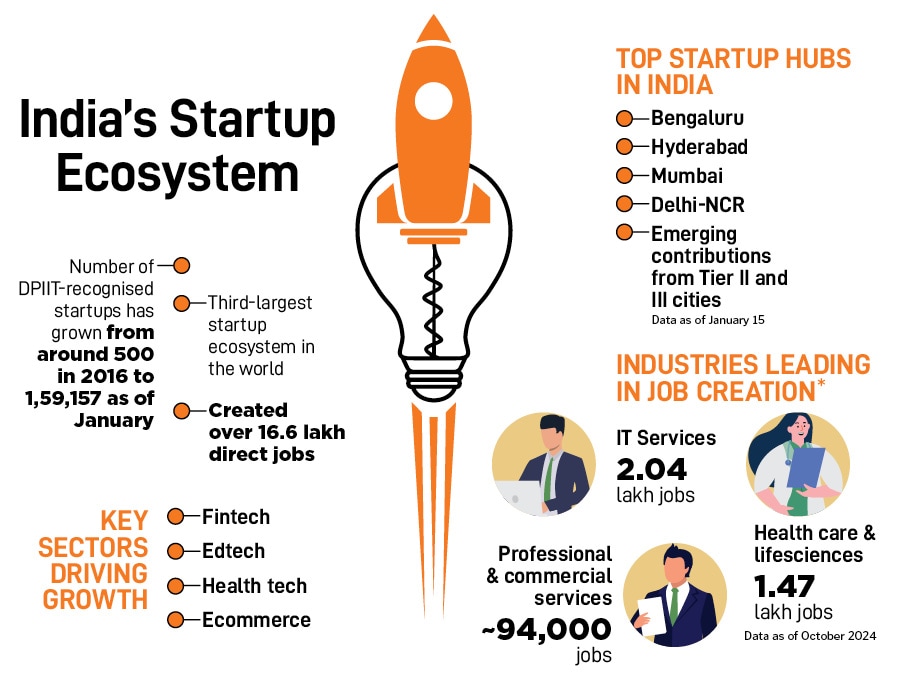

India’s startup ecosystem has come a long way since then. At last count, there were 140,000 officially recognised startups in the country, with more than 115 unicorns among them. These days successful founders are celebrated for creating value, wealth and the thing India needs most: Jobs. They get invited to meet important people, address large gatherings, and enjoy enormous following on social media. Backed by the country’s ever-burgeoning internet users and the shockingly high adoption of digital payments, they now dream of not just serving India but also the world. And they find life partners with ease.

![]()

But every now and then, something happens that roils the waters. A scandal (the most recent being BluSmart), a high-stakes flameout (think edtech), abysmal stock performance of freshly listed startups (more than one), issues of governance and culture, and so on. But the question that rankles the most is, are India’s feted startups just copycats and lifestyle warriors? Or, are they at the forefront of invention and innovation and not only getting valuations but also creating value?

Trade Minister Piyush Goyal spoke for many when he said at the Startup Mahakumbh in April: “Are we content just running shops? Should we aspire to be delivery boys and girls?" He urged startups to move beyond quick commerce and gig work and called for a shift toward deep innovation—semiconductors, artificial intelligence (AI), and global platforms. “Hyper-fast logistics and instant food deliveries may seem glamorous, but they are not shaping the future of the nation," he added.

Goyal’s comments drew swift rebuttals from startup founders and investors. Among them, Aadit Palicha, co-founder and CEO of quick commerce startup Zepto, extolled the contribution of consumer internet startups, such as his own, to economic growth and job creation. “Most technology-led innovation over the past two decades has originated from consumer internet companies. Who scaled cloud computing? Amazon (originally a consumer internet company). Who are the big players in AI today? Facebook, Google, Alibaba, Tencent etc (all started as consumer internet companies)," Palicha said in a post on X.

There is some merit in what Palicha says. But the question is, will India’s consumer internet startups one day become global tech giants? This must be seen in the context of the young status of India’s startup ecosystem (it was not long ago that InMobi’s people were failing to find spouses) compared to the one in the US (where as far back as the 1960s, technology startups were already dreaming big as well as becoming big) or China (which saw enormous government support and a surge in per capita income).

“India is only about 20 years into its startup journey. What the US achieved over six decades, we are just beginning to build," says Kunal Khattar, founder of venture capital fund AdvantEdge, who wrote the first cheque for Rapido, the rapidly surging cab and bike taxi aggregator. “Amazon could rely on FedEx. Flipkart had to build that infrastructure from scratch. It is 10 times harder here because we are often creating both the product and the ecosystem it needs to survive."

![]()

India-first innovation

In 2007, when Flipkart was born in a Bengaluru apartment, its founders often had to explain what ecommerce meant. The infrastructure was patchy, funding scarce and few founders aspired to do anything outside India.

When Razorpay’s Harshil Mathur and Shashank Kumar began raising funds in 2014, Kumar’s grandfather asked: “Why are people giving you money?" Mathur’s father wondered: “When do you have to return it?" Coming from banking backgrounds, they saw venture capital as loan, not equity.

Says Tewari of InMobi: “I think entrepreneurship is about exploring the world which is unknown. So that was our first bet, and I think it has worked out well."

What sets India apart is not just the scale of its market but also the specificity of its problems. For instance, Rapido was set up in 2015 with the simple idea to make daily commute affordable and accessible to the masses—especially in the smaller cities, where ride-sharing was expensive and limited.

“Our mission was to unlock large-scale employment by enabling anyone with a bike and the time to earn a livelihood," explains Pavan Guntupalli, co-founder of Rapido.

Similarly, when PhonePe started in 2015, the digital payments landscape was still an unfamiliar territory. “The startup ecosystem was buzzing with early ecommerce pioneers and wallet experiments, but we were essentially asking a billion people to fundamentally reimagine their relationship with money," a PhonePe spokesperson tells Forbes India in an email.

![]()

Though there was a surge of affordable smartphones and low-cost-high-speed internet, the human element—trust in cash—remained a challenge. The breakthrough came with United Payments Interface (UPI) in 2016. It was not just a payments solution, it was a trust-building exercise in a cash-first economy.

“Suddenly, we were not asking people to trust a startup with their money we were offering them a new way to use their existing bank relationship. PhonePe’s eventual success, greatly aided by the advent of the UPI platform, lay in its ability to address these trust deficits by offering a simple, interoperable, and real-time payment experience directly linked to bank accounts," says the spokesperson.

New-age tech giants such as Urban Company, Zepto, Swiggy, and others are thriving not by replicating global models but by reimagining them to suit India’s needs, driven by innovation rooted in local realities. They are connecting the informal economy to the formal, offline to online, and the underserved to opportunity.

But as India masters the art of solving for scale and specificity, a new frontier emerges—one that demands not just adaptation but also invention.

![]()

Coming of DeepTech

This is where deeptech enters the frame: Startups building foundational technologies in AI, semiconductors, electric vehicles and biotech. A new generation of Indian startups is laying the groundwork for breakthroughs that could rival the best in the world.

In 2023, a progressive farmer told Anoop Srikantaswamy that diesel was too expensive, but electricity was free for farming. That sparked Moonrider, a startup building affordable and rapidly charging electric tractors.

Exponent Energy, which is developing a fast-charging energy ecosystem for electric vehicles, offers batteries that charge in 15 minutes and last over 3,000 cycles. They are targeting commercial vehicles in India and enabling retrofitting of existing internal combustion vehicles.

Unlike consumer-facing platforms that scale fast and wide, deeptech ventures are built on years of research, experimentation, and—often—failure. But they also carry the potential to redefine India’s position in the global tech landscape.

“Deeptech companies take eight to 12 years to build. They need long-term money. That money is not available," says Mohandas Pai, chairman of Aarin Capital and former CFO and CHRO at Infosys. “We are in the midst of an AI revolution. We have to invest heavily to dominate this industry and make sure we don’t become a digital colony for the US."

Srikantaswamy, Moonrider’s founder and CEO, and Arun Vinayak, co-founder at Exponent Energy, agree: The market is ready, the talent is emerging, but the ecosystem—especially capital and policy—needs to catch up.

“The ‘Make in India for the world’ theme needs patient capital—six or seven years of R&D without any revenue. These sectors require a foundational level of engineering and technical development before they can scale," says Srikantaswamy.

Vinayak says India is still far behind China. “The Chinese government has been investing in deeptech and R&D for generations now. And they prioritised vocational training," he explains.

In India, vocational training is often looked down upon. Working in a factory is considered undesirable, and everyone aspires for white-collar jobs. “That mindset needs to shift. We need to become more comfortable with working in hardware, material science and related fields. Much of what India does is ‘dumb manufacturing’: Assembling or producing based on someone else’s technology. We don’t design or innovate the core tech ourselves, and that’s a crucial difference," adds Vinayak.

The landscape is shifting. Indian startups are no longer just following trends. According to Venture Intelligence, India’s deeptech ecosystem attracted $324 million across 35 deals in the first four months of 2025. That is more than double the amount during the same period last year. On June 9, deeptech electric mobility solutions provider Vecmocon Technologies announced the successful closure of its Series A funding round of $18 million. The round was led by Ecosystem Integrity Fund, with participation from Blume Ventures and Aavishkaar Capital.

Though the early signs of investor interest are encouraging, the capital required to sustain long-term innovation, especially in hardware-heavy IP-led sectors, is still scarce. As India’s deeptech momentum builds, the question looms: Who will fund the future?

![]()

The funding problem

Though India may have been a late entrant into the deeptech race, the momentum is building. Both public and private capital are showing renewed interest in backing frontier innovation.

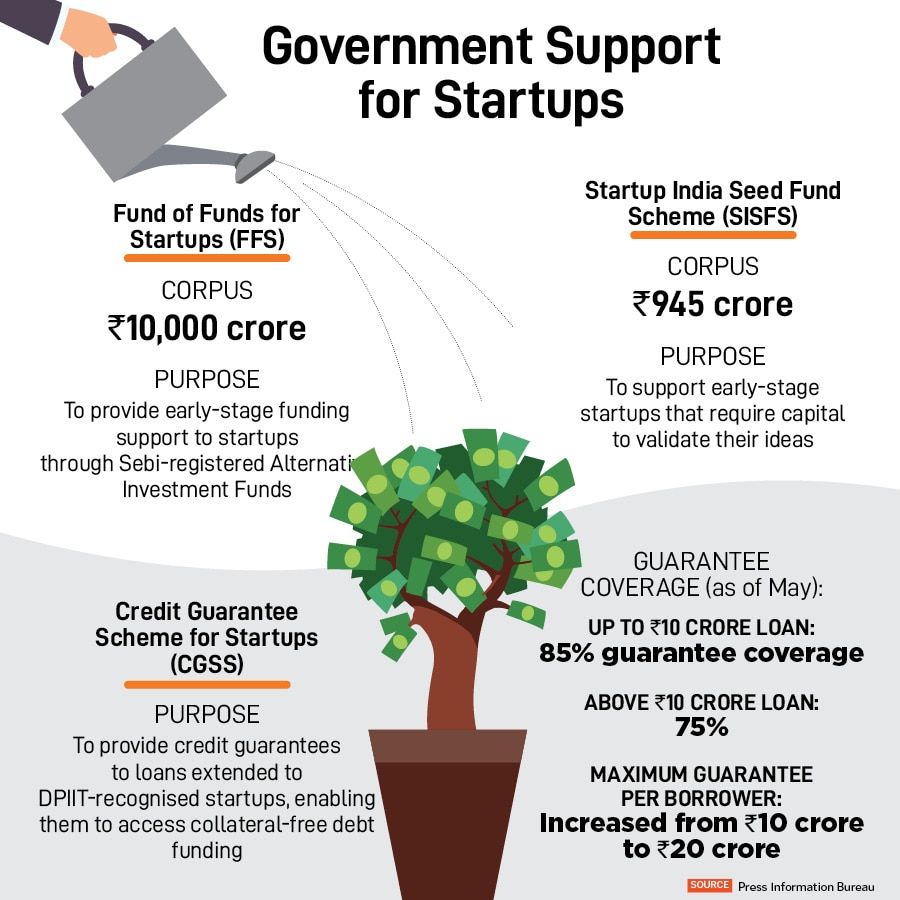

At the Startup Mahakumbh, trade minister Goyal announced the Second Fund of Funds for Startups with a corpus of ₹10,000 crore. A significant portion of the fund will be reserved for seed funding and to support deeptech innovation. “Through this fund, we aim to foster the development of cutting-edge technologies like AI, robotics, quantum computing, machine learning, precision manufacturing and biotech," he said. Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, during her Union Budget speech this year, announced a ₹20,000 crore investment to drive private sector-led research, development and innovation.

Sanjeev Bikhchandani, founder and executive vice chairman of Info Edge, welcomes these initiatives. “What’s great is that the government contributes only 25 to 30 percent to each fund, which forces the rest to be raised from private sources. This creates a 4x to 5x multiplier effect in mobilising domestic capital," he says.

Data from the earlier Fund of Funds shows the initial ₹10,000 crore has already catalysed more than ₹89,000 crore in startup investments.

Pai says the Fund of Funds is a great idea, but more can be done. “India spends ₹115 lakh crore annually across central and state governments. Allocating just ₹50,000 crore to ₹60,000 crore to startups and innovation would be a game changer. Our tax-to-GDP ratio is around 18 percent, translating to nearly $750 billion in annual tax revenue. We have the fiscal space, we just need the political will," he says.

As for private capital, Kunal Shah, founder and CEO of fintech unicorn Cred, strongly believes that leadership is followership. “In VC investing, they look for slope of success, competitive ability, understanding, insight and ability to lead. Hence, VC capital does follow," he says. Shah says raising capital for Cred was only possible because he was an experienced entrepreneur with a successful exit behind him. “We did not monetise the company for the first two-and-a-half to three years. This is only possible if you have the pedigree to say, ‘Trust me, I’m doing the right thing for building distribution first and then monetisation’."

The same principle applies to deeptech. “Where is the large deeptech founder ecosystem or the traction in terms of revenue or scale? Where is the depth of the market cap for us to invest in R&D? So, I think we are still very early in our deeptech journey," Shah says.

Moonrider’s Srikantaswamy agrees: “Right now, it is largely an investor’s market, and raising capital is extremely challenging. Everyone wants to observe your progress, but very few are willing to actually invest." He, therefore, decided to first bootstrap his way. And then, “instead of immediately approaching institutional investors, we reached out to exceptional founders as angel investors—people who had built and exited companies themselves. This helped us gain attention from institutional investors. And then we partnered with sector-focussed funds like AdvantEdge and Axilor", he says.

In several areas, the government has ‘missions’ driving progress. “With the establishment of IDEX, InSpace, the Quantum Mission, the AI Mission etc, the government has taken a definitive and welcome step for private-sector participation," says Padmaja Ruparel, co-founder, IAN Group. “We are seeing a catalytic effect. Funds have begun to raise additional capital for deeptech. Family offices and HNIs (high net-worth individuals) have started to write cheques, and banks have designed debt solutions for these companies."

But there is more to this story. Several new-age technology ventures still grapple with a shallow bench of experienced founders, limited market depth, and sluggish institutional support. As the sector begins to scale, a more uncomfortable issue surfaces: Governance lapses.

Governance gap

The Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi), the stock market regulator, has launched a probe into alleged financial misconduct by the founders of Gensol and BluSmart. The allegations include founder overreach, weak board oversight, and opaque financial practices—issues that crop up with alarming frequency in high-growth startups.

Startup failure is common. It can occur due to multiple reasons: Cash runs out, business model does not work, failure to scale or raise capital. But governance failure can occur even when there is no business failure.

“That is the kind of failure that is truly unpardonable," says Rahul Taneja, who is partner at Lightspeed, a large VC firm. “The first three types of failure are acceptable—they are part of the risk we take… I’d say 99 out of 100 startups do not work out the way they were originally imagined," he adds.

![]()

Byju’s has faced allegations of financial mismanagement, including delayed audits and non-compliance with filing norms. GoMechanic, in 2023, admitted to inflating revenues and fabricating partnerships, leading to mass layoffs and a distressed sale.

“It often comes down to greed or pressure. Sometimes founders are pushed by their investors. You commit to a certain growth trajectory, and then you get caught in that loop. You start with a small experiment, maybe a bit of window dressing, and before you know it, things spiral out of control," explains PB Fintech’s Alok Bansal.

Many new-age founders do not come with a process-and-control mindset and have not worked in jobs that are rooted in governance or compliance. “By nature, they are not wired for process discipline. That’s where the board and investors come in, to guide and support, not pressure them into cutting corners," adds Bansal.

Malintent is not a risk, it is a red flag. Taneja of Lightspeed adds: “You simply don’t want to be in business with people like that. And choosing the wrong raw material—the founders—leads to disaster. Occasionally, there will be a rotten apple. You just hope you are not backing one. That’s why it is critical to run deep due diligence before investing."

Tewari of InMobi agrees that governance lapses are just not acceptable. “The only thing I can say is that boards have not played their part. They can put their hands up and say, we were not aware—that can’t be true. These things don’t happen overnight," he says.

![]()

Chasing global scale

A growing number of Indian startups are no longer just building for India, they are building for the world. Tewari calls the global launch of his Glance AI across 140 countries “the UPI moment of fashion commerce". The goal, he says, is to create a tech-first product that can stand shoulder to shoulder with global giants such as Google and Meta. “It is not about resources anymore, it’s about the mindset."

In health tech, Qure.ai is using AI to transform global diagnostics, enabling early detection of diseases such as tuberculosis and lung cancer through chest X-rays and CT scans. Its tools are now deployed in more than 100 countries. Meanwhile, Razorpay has begun its international expansion, launching in Singapore and gaining traction in Malaysia as it eyes Southeast Asia as a growth market.

“We are producing large tech companies solving India’s unique problems. That is where the opportunity lies. Some of them will go on to solve global problems, too," says Bikhchandani.

![]()

So, what really needs to change?

For starters, India’s startups must shift from chasing valuations to creating value. “As long as you are solving a real problem, scaling responsibly, and not losing money at the unit economics level, you are on the right track," says Bansal of PB Fintech. “But you can’t burn ₹2 to earn ₹1 and have no line of sight on how that will ever improve. I don’t understand those models—that’s not building a business, that’s buying revenue. You are paying someone to show growth." Valuation, he adds, should be a by-product, not the goal.

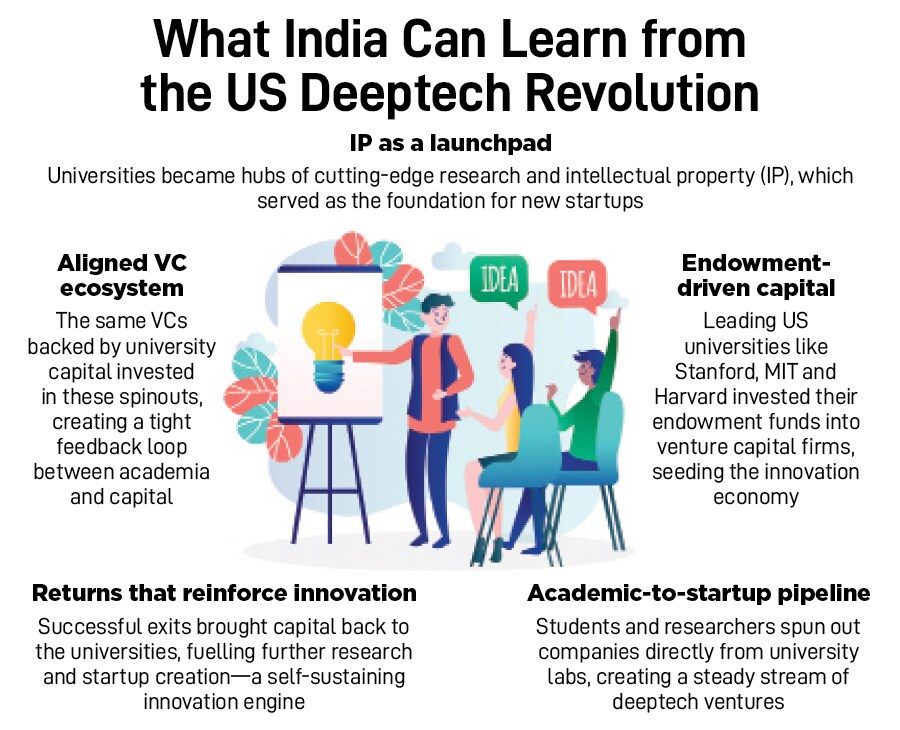

Strengthening India’s R&D ecosystem is critical. Kumar of Razorpay says: “There are some great R&D labs that are funded by the government in the US, China and Europe. This, as an ecosystem, does not exist in India. If you fund R&D labs, it will help attract better quality of talent, which today goes out of the country for PhD. The best people in India don’t stay in research, they go into startups or companies."

Beyond capital and R&D, India needs to build industry-ready talent, especially for deeptech and manufacturing. “There is a lack of people with experience in launching new products in emerging or nebulous technology areas. Software does not face many of the challenges that deeptech or hardware does," explains Vinayak. According to him, building design from lab to field is a completely different game, one that requires an understanding of material science and manufacturing.

Despite the challenges, India has achieved extraordinary success in building its startup ecosystem. Says Pai: “We have built this success with both our hands tied behind our back. But to go further, we need to invest in innovation. We need to fund our young people’s dreams. That requires capital, vision and policy support. It is time we get our act together."