Help at hand: How tech platforms are redefining domestic work

Urban India’s demand for ultra-fast home services is formalising domestic help through tech platforms like Snabbit, Pronto and Urban Company

On the eve of Diwali in 2023, Aayush Agarwal sat on seat 21B on a Kolkata-bound IndiGo flight, eyes closed, thoughts swirling. He had just resigned as chief of staff at Zepto and as he mentally sifted through his options—joining another startup, taking a break, exploring new roles—nothing felt right. And then, in a split second, something did. He remembered the countless times he had called his mother to fly down and help him find someone to clean his home in Mumbai (his work location). The frustration of not being able to find reliable help—even in a city like Mumbai—came rushing back. The irony was hard to ignore: In a world where you could book a flight in seconds, finding a trustworthy cleaner felt impossible.

That was the moment Snabbit was born—not out of ambition, but out of a personal pain point and a realisation that daily home services in India were stuck in the past.

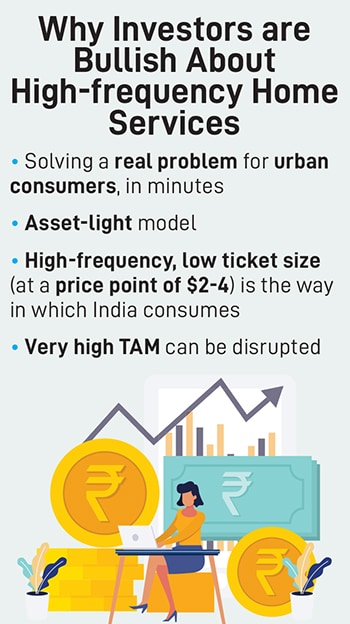

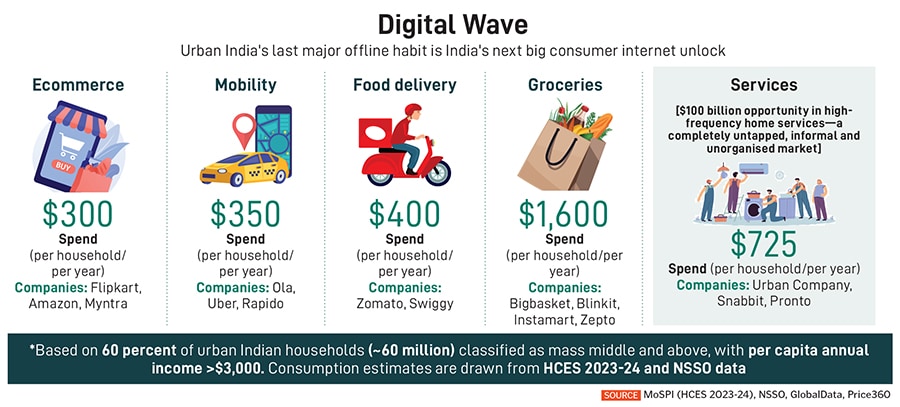

Technology has transformed sectors like ride-hailing, delivery, ecommerce and logistics—bringing structure, transparency and scale to previously fragmented markets. Now, players like Snabbit, Pronto and Urban Company’s Insta Help are doing the same for domestic help. Currently, the high-frequency home services industry in India is around $40 billion and growing fast. Industry experts believe it is likely to touch $100 billion in close to five years.

“I like to call it democratising a category,” says Agarwal, founder of Snabbit. “You take something informal—no price transparency, no feedback loop on quality—and completely reimagine it. Now, it’s just a click: Fixed rates and trained and verified professionals.” Beyond convenience, it’s also about dignity. The model brings respectability to the profession, shifting how society views this workforce—not as invisible help, but as skilled service providers.

At the heart of the demand for these services is the changing Indian urban consumer behaviour shaped by time scarcity. “In dual-income homes, every spare hour has a premium, and services that trade money for time win loyalty,” says Rajendra Kumar Srivastava, Novartis professor of marketing strategy & innovation, Indian School of Business (ISB). Urban life is fast-paced, especially for working parents. There’s a need for quick cleanups or meal preparations before guests arrive. These, Srivastava says, “are not once-a-month deep cleans, they are micro-tasks that repeat often, which can be serviced through a tech platform built for density, reliability and speed”.

At the other end, the rise of the high-frequency quick services model signals a deeper shift for India’s domestic workforce. Srivastava adds, “Historically locked into informal, single-employer arrangements… for many workers, platforms mean higher hourly earnings, reduced payment risk, and even access to training opportunities.”

As platforms like Pronto and Snabbit rewire how urban India accesses domestic help, a key divergence is emerging in their approach to frequency and flexibility. The question isn’t just who provides the service, but how it’s delivered: On demand, subscription or both.

Gurugram-based Pronto, founded by Anjali Sardana, is leaning into all three. Users can book help for cleaning, laundry or even chopping vegetables with three timing options—instant (within 10 minutes), scheduled or recurring. Professionals arrive trained, verified, and in uniform and for those who opt for daily services the same person can show up each day, offering consistency without rigidity.

Pronto’s real innovation lies in its shift-based model, which offers guaranteed hours to workers—a departure from the commission-based gig economy. This not only stabilises income for professionals (who reportedly earn 2-3x more in their first month), but also improves retention and service quality. The company plans to open 10 new hubs over the next 90 days. Over the next three months, Pronto also plans to hire 700 professionals and 50 corporate employees across operations and engineering.

“Workers and consumers are disadvantaged by the disorganisation in India’s domestic labour market,” Sardana said in a statement. “Workers suffer from income instability and consumers aren’t able to get the services they need. We are building a win-win-win business.”

Snabbit started with a subscription model, but quickly abandoned it. The reason? Consumer behaviour had shifted. Agarwal draws a parallel with milk delivery. “We all grew up with doodhwalas. But today, if I asked you to buy the same milk from a doodhwala, you’d probably say, ‘Why do I need that? I can get it in 10 minutes on an app’.”

In a world where flexibility trumps routine, subscription models—once the default—are losing ground. Snabbit’s shift-based system rewards professionals who stay logged in during peak hours, solving urgent, real-time problems. “Urgency comes with price inelasticity,” says Agarwal. “Customers are willing to pay a premium for on-demand immediate service made available in minutes through a single tap. The moment you go offline, you’re no longer offering an on-demand service—you lose bargaining power.”

He says on-demand behaviour is a natural outcome of democratisation. As categories become more tech-enabled, rigid schedules give way to flexible, tap-and-book convenience.

Unlike gig platforms that rely on quick onboarding and low-touch operations, Snabbit has built a high-touch, full-stack model tailored for domestic services—where trust and consistency matter more than speed alone. “We wanted to create a clear distinction between how ride hailing and food delivery partners operate and our experts,” says Agarwal. “Unlike food delivery or ride-hailing, our experts work inside customers’ homes. This makes Snabbit a uniquely high-trust platform, where reliability, training and safety standards are paramount.”

Snabbit’s onboarding process begins with sourcing, done through three channels: On-ground field recruitment in low-income neighbourhoods, digital outreach via platforms like Job Hai and WorkIndia, and referrals from existing workers. Once sourced, candidates go through a three-layer verification—Aadhaar validation, phone linkage and a third-party criminal background check via IDfy. “If anything is flagged, that person cannot go live on our app,” Agarwal says.

Next comes screening and training. Candidates are interviewed to assess intent and background, followed by a three-day training programme at physical centres. The curriculum covers not just task execution—like laundry or dishwashing—but also grooming, soft skills, behavioural training and tech literacy. “We teach them how to use Google Maps, our expert app, even how to ride an e-bike,” says Agarwal. Only those who pass the final assessment are onboarded.

Inspired by the Uber model, Snabbit’s approach is built on hyperlocal precision, predictive demand modelling and real-time availability. Instead of central hubs, it operates a decentralised network. It predicts demand in nano-markets (ultra-small clusters) and places service professionals at hotspots, which are imaginary points on the map near expected demand centres. “We might anticipate 10 orders from a certain society within a neighbourhood,” Agarwal explains. “So, we place professionals nearby and ensure they’re logged in by the set time. When a customer places an order, they’re matched instantly.”

Unlike delivery platforms where mobility is key, Snabbit’s professionals often walk to jobs and spend one to three hours inside homes. That means the network design has to be even more granular. “Micro markets aren’t enough, we need nano markets,” Agarwal says. “We build service radii of just 700 to 800 metres. our experts operate within that radius.”

To ensure availability, Snabbit uses geotagging. Professionals must log in from within a defined radius—typically 200 metres of a hotspot—to be eligible for bookings. Once live, a real-time algorithm matches them with incoming demand. “It’s like Uber,” Agarwal says. “Not every driver is constantly on a ride. But with enough density, the moment one ends, another begins. That’s how our model works too.”

The model is designed for high-frequency, short-duration tasks. And while not every professional is guaranteed a booking, the system improves with data, allowing Snabbit to forecast demand more accurately over time.

Also read: India's gig workers — Central to how cities function but still remain on fragile ground

At first glance, the domestic help service may seem worlds apart from grocery delivery, but the underlying consumer behaviour is similar. Just as quick commerce thrives on low-ticket size and high frequency, platforms like Snabbit and Pronto are tapping into the same rhythm for home services.

There’s a key difference, though: Extremely low capex. Unlike grocery delivery, which depends on dark stores, warehousing and logistics, this model is asset light. There’s no inventory, no working capital and no physical infrastructure beyond training centres.

“It’s not difficult to be profitable with this approach,” says Agarwal. “Our profitability comes from reducing inefficiencies, like idle time or long walking distances and shaping demand and supply accurately.” This lean setup allows platforms to scale quickly while keeping unit economics intact. The real investment is in technology and network design, ensuring that service professionals are placed close to demand and matched in real time.

The model also works because it aligns incentives across the board. Workers can choose their shift hours—ranging from four to 12 hours—and earn ₹12,000 to over ₹20,000 per month. That autonomy is attracting new supply, especially women. “It’s not just about higher income,” Agarwal says. “It’s about greater control over time. That’s why we’re seeing real democratisation on the supply side, and not just demand.”

Snabbit also offers minimum guarantees to its professionals. If the platform doesn’t earn enough commission from a job, it still pays the worker—prioritising earnings over margins. “We don’t want to make money by undercutting anyone,” Agarwal says. “The structural solution lies in efficiency.”

And that efficiency is driven by hyperlocal optimisation. If a worker can walk 200 metres instead of 400 metres between jobs, they can complete more tasks in the same time, thereby earning more without increasing prices. “We prefer sticking to a price range of ₹150 to ₹200 per hour, which is a sweet spot for Indian consumers,” adds Agarwal.

Experts believe this segment—high frequency, low-ticket size—is at the intersection of the total addressable market of a Rapido and Zepto, and the profitability model of Urban Company.

“The biggest digital consumer businesses in India have been built on high frequency and low average order value categories—from Zomato and Zepto to Meesho… the pattern is clear and each of these businesses demonstrates that the key to unlocking massive consumer TAM (Total Addressable Market) in India is through categories that drive high frequency use cases,” says Rahul Taneja, partner, Lightspeed. “Home services is the last bastion of large consumer categories for urban India where a digitally native business will get built, and early traction is validating this thesis.” Manish Advani, principal, Elevation Capital, agrees. “The lower complexity of task and high frequency use case enable scalability of players in this segment.”

Snabbit’s average customer transacts 30 times a year, Agarwal says. “That kind of frequency explodes the TAM. Even someone living in a chawl can say, ‘My mom is unwell, I’ll book someone for ₹150’. That’s India. That’s how consumption works here.”

Snabbit may have started with domestic help, but its ambitions stretch far beyond. The company is preparing to pilot a new vertical for home cooks starting October, a move that signals its intent to dominate the broader category of non-inventory, high-frequency services.

“Drivers, cooks, doctors—anything that’s high frequency. The sky is the limit,” says Agarwal. “We won’t do specialised inventory-based services like deep cleaning or spa setups. We want to do everything that is no inventory, high frequency, and low-ticket size.” Professor Srivastava feels this could be expanded to advanced services like child and elder care, but those would require even higher levels of trust and training.

This expansion reflects a broader shift in how platforms are thinking about service delivery. According to Srivastava, the real differentiator won’t be speed alone, but “locking in the supply side and the workers… that is more important in such a service delivery model”.

Srivastava believes the next frontier will be layering financial products—insurance, loans and wage-linked benefits to truly formalise the informal workforce.

After a year of quietly refining its model in Powai in Mumbai, backed by Nexus Venture Partners, Snabbit began scaling in early 2025. The first six months saw expansion into 27 micro markets across three cities, with plans to reach 200 micro markets in six months, targeting hubs like NCR, Pune and Mumbai. “The year 2024 was all about building the business model. There was no competition back then—no noise in the category,” Agarwal says. “Now, we’re growing at 20 to 25 percent week-on-week.”

The company has raised $25.5 million across three rounds, with only $3 to $3.5 million spent so far. A new fundraise is expected in one or two quarters, but Agarwal insists finding the right partner is more important than chasing valuation. “Valuation is just 5 to 10 percent here or there. What matters is conviction. Building a category-creation business isn’t easy… we’ll have our share of highs and lows. Having the right partners by our side is always more important.”

As the high-frequency home services space heats up, the question isn’t just who entered first, but who can execute faster, deeper and smarter. Snabbit believes it has a headstart.

“I think of this journey like a relay race,” says Agarwal. “Imagine there are four laps to run, and we’ve already completed the first lap ahead of everyone else—even before the race officially started.” Snabbit was one of the earliest players to build specifically for this category, and Agarwal claims its depth of understanding, tech stack and operational model give it a strong lead. But he’s clear about what it takes to win. “Ultimately, it all boils down to who executes better and faster,” he says.

In cities like Mumbai and Bengaluru, where both Snabbit and Urban Company operate, the battle is increasingly local. It’s not just about presence, but also about who’s winning in each micro market.

Snabbit’s and Pronto’s models are also structurally lean. Service professionals use e-bikes, not expensive vehicles, and there’s no separate delivery layer—the person who performs the service travels to the location. “So it’s not just low capex, it’s almost no capex. That’s the beauty of this model,” says Agarwal.

The lean infrastructure is something that excites investors. “House help is the highest frequency services category. Supply training and management will be a key moat,” says Suvir Sujan, managing director at Nexus Venture Partners, one of Snabbit’s earliest backers. “The Snabbit team’s vision and execution on the ground has been impressive.”

Urban Company isn’t far behind. And it’s betting on speed and density to win. Its Insta Help offering is built on the insight that urban consumers increasingly expect services to be as instant as their deliveries. “Historically, we’ve seen people liking same-day deliveries,” says co-founder Abhiraj Bhal. “There’s been a latent behaviour for more instant needs. Some categories just work on instant delivery. For instance, if your air conditioner breaks down, you want someone now, not after three days.”

Urban Company is rolling out pilots in cities like Bengaluru, where users can see professionals available within 30 to 45 minutes. “You’ll see a tab on the app showing all service professionals available within 30 minutes or an hour,” Bhal says. “It’s a high priority for the company.”

The challenge, however, is operational. Delivering instant service in a gig-based model requires scale and density, something Urban Company has built over years.

“It’s no cakewalk,” Bhal admits. “But consumer demand for instant gratification has coincided with our evolution toward micro market density—which makes it easier for us than for a newer or smaller company.”

So, who wins? It may come down to execution speed, local dominance and how well each platform balances scale with service quality. Snabbit claims to be doubling every month and prioritising growth over short-term profitability. Urban Company brings brand recognition, operational maturity and a proven playbook.

The race is on—and it’s being run in nano markets, one household at a time.

First Published: Sep 18, 2025, 12:36

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Sep 19, 2025 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)