When IndiGo ran out of pilots

The airline’s December fiasco was not a scheduling failure alone. Pilots spill the beans about the fractures in training, rostering, working conditions and the industry’s shrinking captain pool

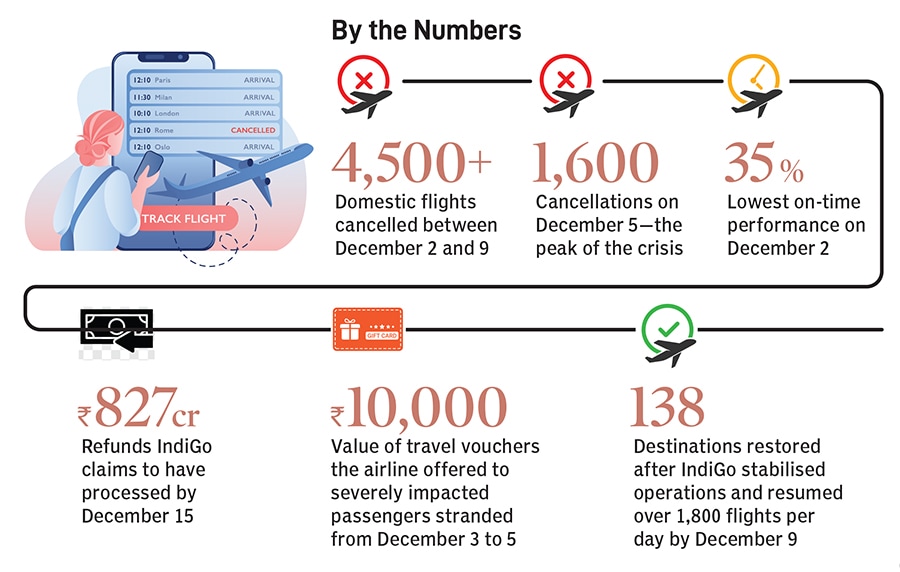

IndiGo suffered one of the most severe operational breakdowns in recent aviation history in December. The airline, which controls over 65 percent of India’s domestic market, buckled under the revised Flight Duty Time Limitation (FDTL) norms, which came into effect on November 1, leading to thousands of flight cancellations and inconvenience for lakhs of passengers. What began on December 2 escalated by December 5, when approximately 1,600 IndiGo flights were cancelled in a single day and the airline’s on-time performance (OTP) came down to 35 percent after maintaining nearly 90 percent in recent months.

The collapse reveals a deeper structural issue in Indian aviation: The long and slow erosion of pilot working conditions and the industry’s dependence on fatigue-inducing rosters optimised for utilisation rather than human physiology. “On an average, I flew 60 to 70 hours a month, but my total monthly duty time was often 140 to 150 hours, at times, even more. Discontent among the fraternity was growing as rostering became more aggressive,” a former IndiGo pilot who spent over 10 years with the airline told Forbes India. “You are required to report an hour before, but you are paid only for flight hours. Turnarounds and post-flight work are not the same.”

Apart from this, first officer entry salaries have either remained stagnant or gone down over the last decade. This, even as training costs have shot up exponentially, creating debt burdens for cadet pilots. An Akasa Air pilot with less than five years of experience reveals that the in-hand starting salary across airlines now is between ₹1.2 lakh and ₹1.5 lakh a month—a figure that, another pilot shares, was their starting package even in 2010.

Industry veteran Captain Shakti Lumba, who headed Alliance Air and retired as an IndiGo executive, says, “IndiGo was caught between a rock and a hard place. It had increased its winter schedule and didn’t have enough pilots to run it. The system started breaking down, whether it was communications or something else, everything went down. It was incapacitation.”

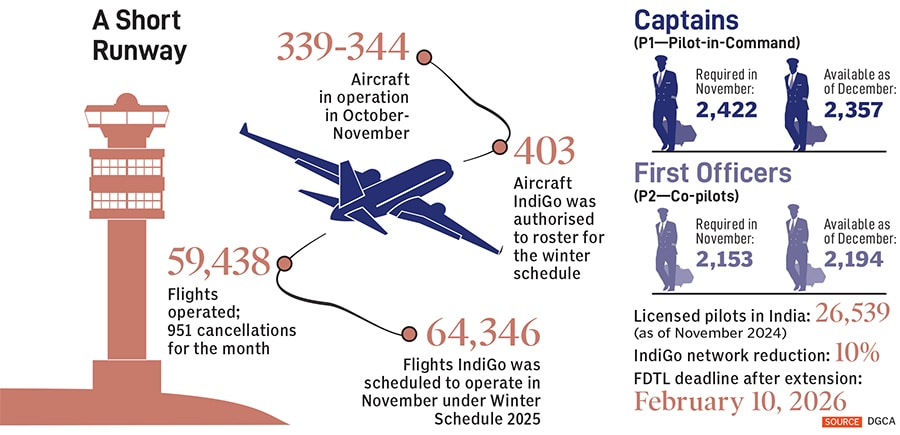

The disruption, though, was not sudden. IndiGo had got approval to operate 64,346 flights in November under the Winter Schedule 2025. However, government data shows it flew only 59,438 and cancelled 951. IndiGo did not fly the remaining planes that had the approval. Forbes India reached out to IndiGo, but the company declined to comment.

The Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) says IndiGo’s cancellations were triggered by “misjudgement and planning gaps”, a sharp increase in night-duty assignments and a failure to anticipate the number of captains required under the revised fatigue norms. It also confirms pilot roster estimates “exceeded their anticipation”, resulting in delays. The aviation regulator issued a showcause notice to IndiGo’s CEO and COO on December 6.

IndiGo’s winter schedule was built for peak traffic: Around 2,300 flights daily and high aircraft utilisation across major hubs. The revised FDTL rules redefined night duty, increased mandatory rest and capped night landings. And the airline could no longer stretch its existing pilot pool across the same network.

According to pilots Forbes India spoke with, the airline had been operating with a thin captain bench for months. Insiders say the company froze hiring last year despite knowing that it would need more pilots once the FDTL norms kicked in.

A veteran captain with more than 30 years of experience in a major Indian airline recalls a time when the profession was defined by heavy investment, high training standards and employer-funded career progression. “Once a pilot was recruited, all endorsements were bought by the industry. I was qualified on the Fokker 27, then the 737 and A320… I did not have to pay anything, I did not have to sign any bond,” he says.

That system has been replaced by one in which trainees shoulder the financial risk. Captain Lumba says the turning point was the rise of private carriers after deregulation, and particularly IndiGo’s scale. Airlines moved to cadet-pilot pipelines in which candidates pay for their commercial pilot licence (CPL) and type rating, often abroad, through training partners approved by the airline. The promise was simple: Complete the programme and get a job. However, the model expanded faster than the industry’s capacity to absorb new pilots.

The former IndiGo pilot quoted earlier says he spent around $50,000 (₹25-26 lakh based on the exchange rate at the time) for CPL training in Memphis, US, in the mid-2000s and roughly ₹50 lakh for an Airbus A320 type rating abroad before joining the Indian market leader. “As a first officer, my initial salary was around ₹1.4-1.5 lakh. It was a decent return because IndiGo was expanding fast,” he adds. “But for people who joined later, the economics looked much worse. Credit programmes now ask for ₹1.1-1.2 crore for CPL while the starting gross package has reduced substantially. The return on investment is questionable.”

Others who have undergone training say they have paid astronomical sums between ₹1.25-1.5 crore for first officers’ training before they got a chance to fly a commercial jet. Many take loans and find themselves immersed in debt for a large part of their careers.

In a written response to a parliamentary question on December 11, the government said CPL training fees in India are market-driven. It clarified the DGCA does not regulate the fee structures and that there is no proposal to introduce scholarships or financial assistance for minority, scheduled caste/scheduled tribe candidates or girls.

The cost-to-income mismatch is further exacerbated by employment bonds. Earlier cohorts faced two-year commitments tied to company-sponsored training. Newer cadet graduates face far heavier terms. The Akasa pilot mentioned earlier explains the bonds make sense when the company is funding a trainee’s type rating or advanced training; in such cases, a bond simply ensures that the pilot stays long enough for the airline to recover its investment.

The problem, pilots say, is bonds expanded sharply even as the cost burden shifted away from the airlines to individuals. The former IndiGo pilot says bonds rose to five years linked to payments of ₹50 lakh if the pilot left before completing it. For trainees who borrowed heavily to fund their CPL and type rating, the bond effectively locks them into the airline for a significant portion of their early career.

Notice periods add another layer of control. The former IndiGo pilot says a standard three-month requirement has expanded to six months across ranks. And there were attempts to push it to a year. “Six months is unusually restrictive... a well-run airline can forecast requirements within a month or two,” he explains.

As training costs shifted to individuals, experienced pilots began looking at greener pastures overseas. “The Middle East is attractive,” says another former IndiGo pilot. “Pilots I know who moved there often don’t want to come back.”

Better pay, predictable rosters and stronger bargaining structures pull experienced commanders away even as domestic demand intensifies. The Akasa pilot agrees, saying many of their peers were exploring opportunities abroad or considering leaving the profession.

Lumba believes that a real pilot shortage will force the industry to improve conditions. “It’s a classic case of supply and demand. If shortage hits, pay will rise, and more training providers will emerge,” he says.

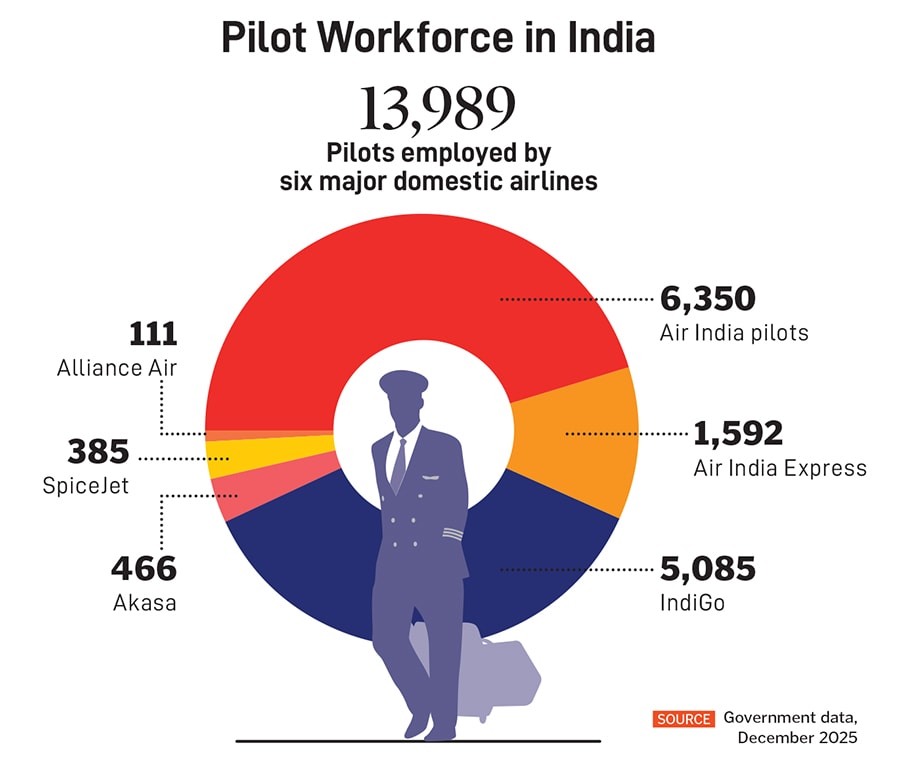

Media reports suggest IndiGo will need to hire 900 pilots by February. The question is where will the new pilots come from?

One pilot says getting first officers should be easy. The airline has a partnership with Canadian simulation and training firm CAE, which resulted in 941 cadets being inducted as junior first officers between 2011 and 2023. However, the problem lies with captain shortages. Command requires an Airline Transport Pilot Licence, thousands of hours of flying, and specific pilot-in-command experience that accumulates only over years. In the short term, airlines have limited options to acquire captains. They will have to accelerate upgrades for eligible first officers, attract captains from rival airlines or recruit from abroad under temporary authorisations.

Military pilots represent a valuable talent pool, but their movement into civil aviation is neither rapid nor routine. A retired senior Indian Air Force officer explains military experience is recognised when applying for a CPL, but conversion requires DGCA exams and meeting civil medical standards. “You can only join commercial airlines after you leave service,” he says, adding that India does not have a policy, common in parts of Europe, where military pilots operate commercial aircraft in case of a shortage. For those who do transition, experience is considered, but medical fitness is a limiting factor.

Hiring foreign pilots has also been restricted by policy. Temporary authorisations may cover shortfalls, but the government prefers to prioritise domestic workforce development, limiting the speed at which airlines can plug shortages.

At the heart of modern airline crew planning is the ‘optimiser’, a software engine that builds pilot rosters by maximising aircraft utilisation within regulatory limits. In principle, the optimiser allocates flying duties, standby periods and rest windows by processing vast amounts of operational data—aircraft schedules, airport slots, duty-time regulations and crew availability. Pilots lament that the tool is designed to prioritise efficiency rather than human physiology.

An Akasa pilot says the optimiser can assign rest periods at odd times, rotate crews between early-morning and late-night duties, or place standby shifts in ways that disrupt sleep cycles. Even designated rest periods may not be optimal when pilots find themselves rostered in cities away from home.

The United States Federal Aviation Administration’s scientific advisory panel shows that even high-quality rosters leave ‘residual’ fatigue because circadian rhythms cannot adjust quickly to rotating schedules. Extended wakefulness, irregular duties and compressed rest periods impair cognitive performance.

After the IndiGo fiasco, the government intervened swiftly. Temporary relaxations, including exemptions on night landings and adjustments to rest rules, allowed the airline to stabilise operations. IndiGo restored over 1,800 flights a day by December 9, claims it processed refunds of ₹827 crore and pledged compensation to travellers.

That does not take away from the problem staring at the sector. Workloads have increased as the industry scaled, rosters have tightened, salary progression in some categories has slowed and bonds have become heavier. Yet demand continues to rise: India remains one of the fastest-growing aviation markets in the world.

During the launch of the Electronic Personnel Licence in February, Civil Aviation Minister Ram Mohan Naidu had said India would need about 20,000 pilots in the near future. But growth without buffers comes with risks, as the IndiGo crisis has shown.

First Published: Dec 20, 2025, 10:41

Subscribe Now