The gig economy, reimagined: Inside Urban Company’s playbook

Urban Company’s DNA is changing from ‘service’ to ‘consumer’. What are the implications as it readies for life as a listed firm?

A decade ago, at Hotel Grand in New Delhi, Mridul Arora, partner at Elevation Capital, met the co-founders of Urban Company: Abhiraj Singh Bhal, Varun Khaitan and Raghav Chandra. Like most young people dreaming of building the next great startup, Arora found the trio to be full of dreams and promise. What’s more, he found them focussed on consumer pain points that were very real.

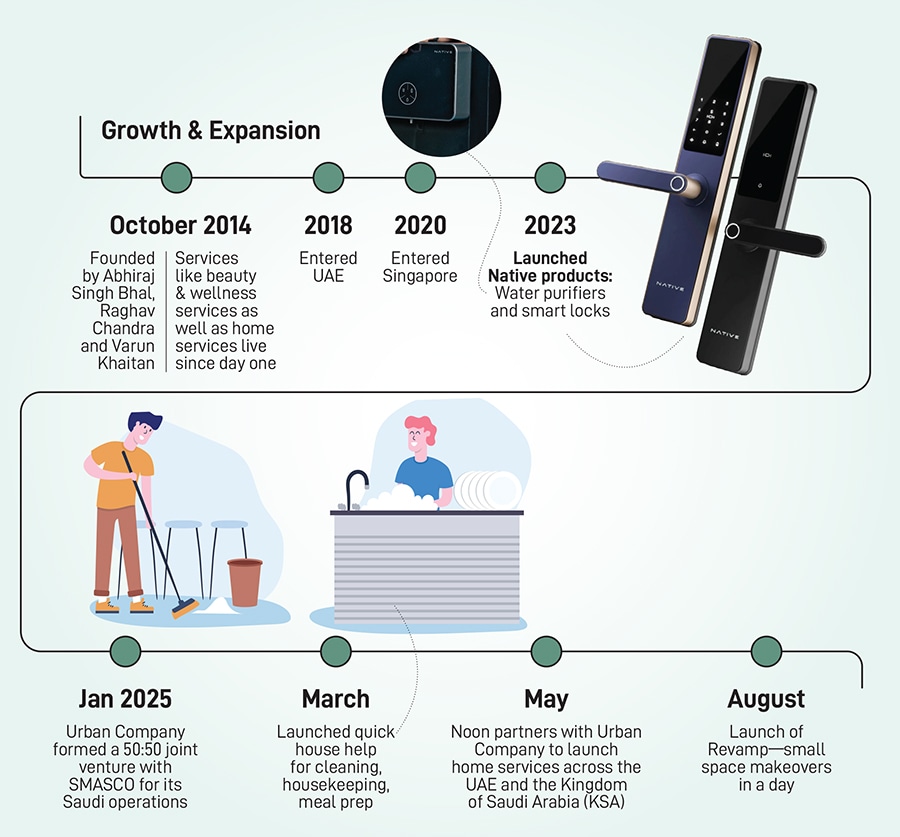

Back then, the startup was called Urban Clap, and its avowed mission was to bring providers of home services on a digital platform, raise the quality of their services, make the pricing transparent, bring in accountability, and make payment seamless. Over the years, as it rebranded itself as Urban Company—as it prepared to venture into international markets, it was important to have a more universally appealing brand and avoid the negative connotation of ‘clap’ in western slang. Its services grew to what in startup lingo is called “full stack” beauty and wellness and home services.

Back then—though it was not that long ago—urban dwellers’ nightmares consisted of occasions when they needed an electrician, carpenter or other such handymen. You knew them but struggled to get hold of them and struggled some more to get them to come and do a job. The pricing involved a mix of haggling and generosity. You went out of your way to make sure the fellow did not mind visiting your home again—should the next nightmare strike.

“We saw a very large market which was still unorganised, very fragmented and broken,” says Bhal, who is the CEO. Consumers were not getting the experience they were ready to pay for. Service providers were not part of the formal ecosystem and relied on local operators, or middlemen who controlled access and appropriated much of the margins.

Arora says: “Every micro market had local service providers, but reliability, quality and consistency were major issues. Urban Company’s team stood out for its ambition to solve this problem with technology.” Elevation Capital was one of the earliest backers of Urban Company, investing in it in December 2014 and, in the runup to its IPO (initial public offering), held 10.84 percent equity. It has invested a total of $14.7 million in the company to date.

The founders saw an opportunity that could be tapped by training the service providers, giving them the right tools, and bringing them into the formal ecosystem. This would also increase the service providers’ wage earnings, and high-performing ones would get life, accidental and health insurance as well as loans and other financial help.

Alongside, the rise of gig work has been restructuring the country’s workforce. Driven by digital connectivity and urbanisation, India’s gig workforce has ballooned from 8 million in 2020 to 12 million in 2025. Estimates suggest that this workforce, mostly young people aged between 18 and 23 and seeking a secondary income, will double in the next five years.

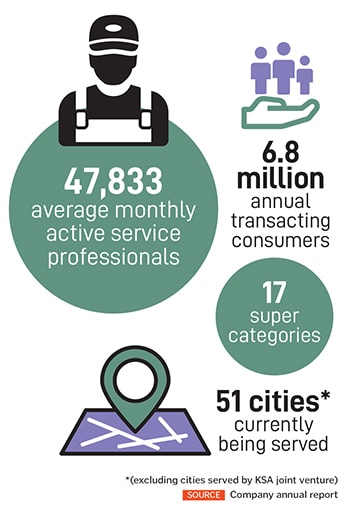

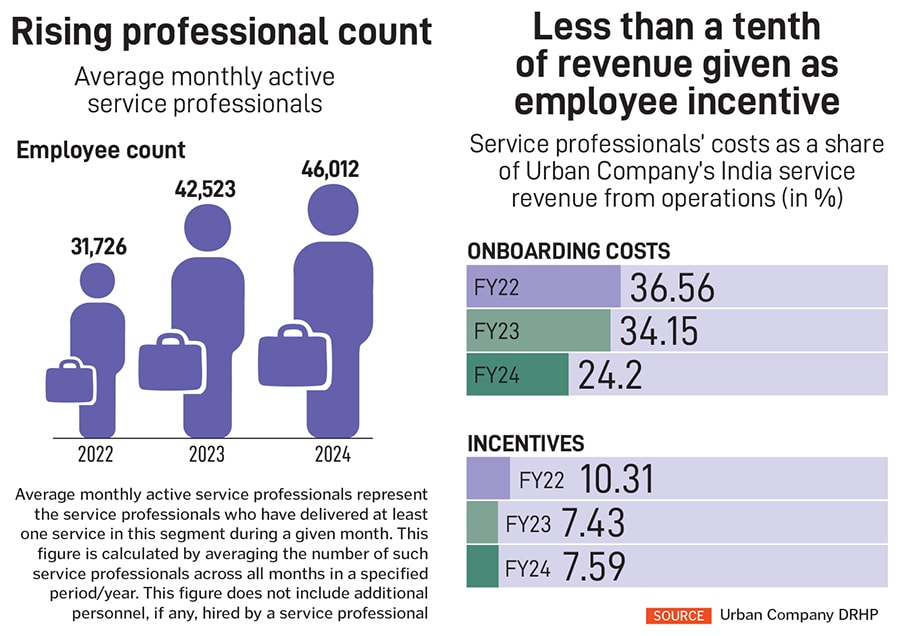

Meanwhile, Urban Company’s average monthly service professional count jumped 45 percent between 2022 and 2024 to 46,000. It claims to have 6.8 million annual transacting users across 17 super categories in 51 cities, with a total net transaction value of ₹3,271 crore (in India and overseas). Over time, it has rationalised its business streams, shutting down those that were difficult to scale and entering new ones. But some things remain unchanged.

“I was recently looking at our first investor pitch deck from 2014,” recalls Bhal, “and, interestingly, it started with the same vision statement—of being the player that organises the industry, brings in reliability for end-users, and formalises gig work.”

In March, Urban Company started InstaHelp to take its digital platform into that most unorganised of home services: House help. The intent is to make someone available for cleaning, cooking or housekeeping in quick time, while maintaining the ethos of transparency, accountability, pricing and payment. It started as Insta Maids, which had to be changed in the face of a social media furore.

“I think we could have been more thoughtful about the choice of name,” says Bhal, and, on a lighter note, adds: “I think we are a company that gets the brand name right the second time.”

He is now getting into a territory where second chances can be tricky, because the stakes are high and fortunes can change in the course of a day, maybe quicker. In the runup to it, Urban Company appears to be tinkering with its DNA by blending its service ethos with products.

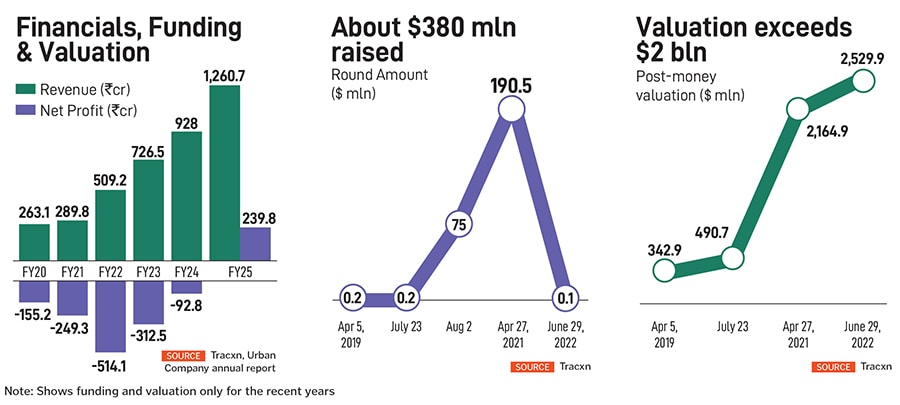

Urban Company’s IPO was slated to open on September 10, while this magazine would be getting printed, and close two days later. The price band is ₹98 to ₹103 a share for a float intended to raise ₹1,900 crore. Reports said its shares in the grey market werebeing quoted at premiums that would likely translate into listing gains of 18.5 to 27 percent over the upper end of the price band.

Days before the IPO was to open, Urban Company conducted secondary transactions totalling ₹500 crore, with Elevation Capital, Prosus, SBI Mutual Fund and Permira buying shares from Tiger Global and Accel—the latter two are large venture capital firms and early investors in the company. The transaction is reported to value the firm at ₹15,000 crore, which is close to the market capitalisation it is expected to have once it gets listed on stock exchanges after the IPO.

These are good tidings and can be seen as an endorsement for the tweaks in Urban Company’s fabric in recent times. It has had products since 2016-17, which were sold to the service professionals on its platform. These included facial tool kits, manicure and pedicure kits, and spare parts for water purifiers under the brand name, True Water.

“Over the last two to four years, we saw that there was a great adoption of these water filters and spare parts within our ecosystem of service providers,” says Bhal. The next logical step was to launch products for consumers at large. After two years of R&D, Urban Company launched its Native brand of water purifiers in October 2023.

“It is a product that does not require to be serviced for two years and can be controlled through smartphones—completely different from the traditional razor-and-blade model most purifier companies follow,” says Arora of Elevation Capital.

The Native brand has now been extended to smart locks. That looks like a definitive step towards becoming a consumer company. “If we thought of ourselves as a service company, we should have launched a product which, just like all the other products out there, needed continuous servicing, because it would allow us to make more money on the service, right? But we don’t think of ourselves as a service company,” says Bhal.

However, the founders do not think that the launch of Urban Company’s product line is a pivot. “This was a natural evolution and extension for us. We have always seen ourselves as a home services and solution company,” says Bhal.

Contrary to the buzz in the news media, he says there is no plan to add any more products to Urban Company’s basket in the near future. Already, though, Native is making its presence felt, bringing in ₹116 crore in revenues in 2024-25, or 9.2 percent of Urban Company’s total revenue last financial year.

“It is definitely growing fast, and we expect it to grow rapidly. But [it is] hard to predict how large it will become, because it is still early days for us,” says Khaitan, the co-founder, who is the COO.

The Native products now come from a contract manufacturer. “It is a dedicated line for us, so we are controlling the experience on the line, quality and testing,” says Bhal.

InstaHelp, according to the company, racked up a wait-list of more than 500,000 within days of its launch. “I remember there was an Instagram post announcing the launch and how you can book this service. There were 10,000-plus comments on it, and 90 percent of the comments were from people leaving their PIN code, asking us to launch there,” says Bhal.

Urban Company’s latest offering is Revamp, which promises to renovate a part of your house in a day. This includes at-home consultation. Materials are to be delivered in advance. The service is currently available in Mumbai, Delhi NCR, Bengaluru and Hyderabad. A day is indeed fast for renovating a house, even just one part of it.

Urban Company is focusing on speed in other areas as well. “There are some categories which just work for instant deliveries. For example, if your air conditioner broke down today, you want someone right now, not after three days. Or for a spa, I wake up on a weekend and if I want a little bit of pampering, I want someone now,” says Raghav Chandra, the co-founder, who is also the chief technology and product officer.

There are pilots running in select cities for Insta, which makes services available in 30 to 45 minutes. “This is a high priority for the company,” says Bhal.

Quick commerce for products is centered on dark stores, which players such as Zepto, Blinkit and Swiggy are setting up with extraordinary zeal. But how do you add speed to service? That will require professionals to be available in 30 to 45 minutes for a range of services.

According to Bhal, his company has the advantage of scale and density. “If you have density on your side, it is not that challenging,” he says.

Arora of Elevation Capital says it also has to do with the extensive recruiting and training of service professionals. “Today, they run one of the most extensive physical training infrastructures in the country. And they have standardised everything from uniforms to service protocols, and even built a dedicated products business unit,” he adds.

Urban Company stepped outside India in 2018, motivated by the realisation that the same needs and gaps existed in many other countries. It is now present in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Singapore, and Saudi Arabia. “In markets where similar platforms exist, we have opted for partnerships to scale faster and more efficiently,” says Khaitan.

Recently it tied up with West Asian ecommerce giant Noon to offer home services directly through the Noon app in the UAE and Saudi Arabia. “Urban Company gains access to a complementary audience while Noon expands its ecosystem beyond commerce and fintech into everyday services,” says Khaitan. “We are open to more such partnerships.”

Forays into Australia and the United States did not work out. “If I look back at the last 10 years of Urban Company, there have been many failures, just like there have been many success stories. It is part of the game of building a company. No risk, no reward,” says Bhal.

That does not appear to quell the company’s appetite for risk. “We will take risks,” says Khaitan. “We will do things that at the time may not logically make sense in a classical case study format… But we learn from every bet.”

Suchita Dutta, executive director of the Indian Staffing Federation, says the rise of gig work is a double-edged sword. While acknowledging that it financially empowers some workers, particularly women, she emphasises that it often diminishes quality of life due to uncertainty and lack of support.

“Workers face physical hazards such as road accidents and psychological stress from irregular pay, leading to burnout, anxiety, depression, poor sleep, and social isolation,” she says.

Anamitra Roy Chowdhury, assistant professor at the Centre for Informal Sector and Labour Studies, agrees, and stresses that lack of legal clarity is the biggest hurdle. “They (gig workers) are not legally identified as workers. They are considered independent partners and not employees of the platform. This is a big legal loophole,” he says.

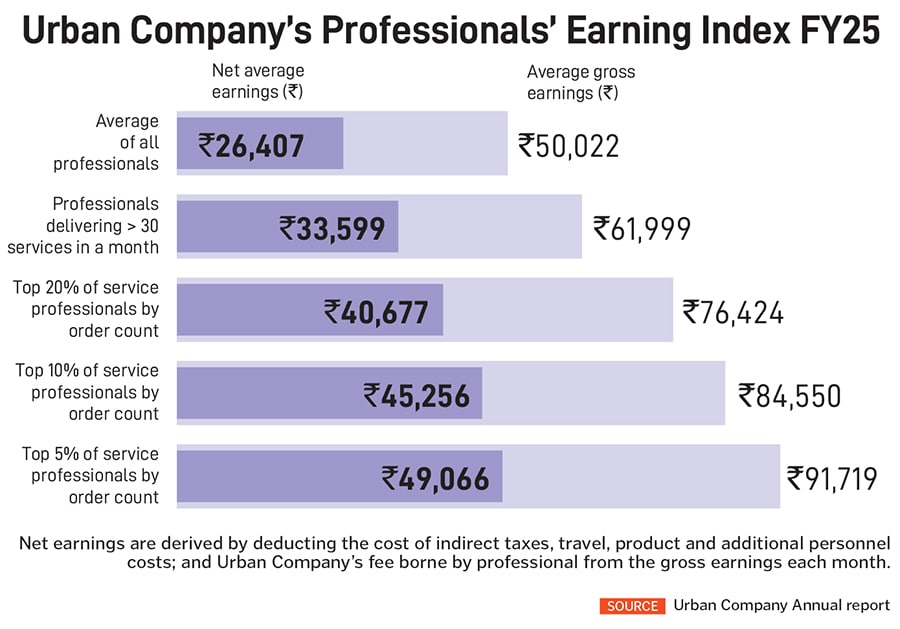

Urban Company typically charges 20 percent to 35 percent commission on each service booking, depending on the type of service, performance and earnings, and subscription or loyalty programmes.

Bhal says an average Urban Company service professional makes about ₹26,500 a month, net of expenses, or ₹3,18,000 a year. India’s per capita income is ₹2 lakh. That, according to Dutta, means an Urban Company professional is better placed than 78 percent of the gig workers in India.

Forging a structured regulatory framework, Dutta argues, is essential to balance flexibility with worker protection. This is critical to ensure fair wages, financial inclusion, and job creation, which could ultimately add 1.25 percent to India’s GDP. “India’s Code on Social Security 2020 is a step forward, but full implementation is needed to address health and economic vulnerabilities,” she says.

Urban Company has integrated artificial intelligence (AI) across its operations—from having customer support chatbots to multilingual voice bots for service professionals. “What the internet, the mobile phones, or smartphones did to us… I think right now, we are seeing the very early days of a paradigm shift,” says Chandra. “Partners are extremely happy. It is like the most empathetic listener you’ll have,” he adds, describing how GenAI-powered bots switch languages mid-conversation and offer real-time assistance.

AI guides service professionals through SOPs, audits service quality through photos, and recommends personalised training modules. “It is almost like the Iron Man suit… reminding them of the checklist to be followed, SOPs to be followed, capturing the inputs and telling them what can be corrected,” says Chandra.

With the benefits come challenges, posing awkward questions about low-skilled jobs and making upskilling a matter of survival. However, Chowdhury says gig work focussed on service delivery, like the beauticians of Urban Company, will likely remain unaffected, because they “cannot be replaced” by automation.

Dutta says platforms such as Urban Company will remain central to determining wages and conditions. “They should ensure transparent payments, safety training and accountability in triangular relationships,” she adds.

For users, gig platforms offer access to services that were previously inconsistent or unavailable. For service providers, flexibility is the key. They can choose the hours and days to work. This can help them plan their day and manage their other responsibilities, be it receiving children back from school or care for the elderly. For women, especially, the gig model offers a way to balance maternity breaks and family responsibilities with meaningful work.

“You ask them why they like Urban Company and earning is a very big part. And then flexibility is a very big part,” Khaitan adds.

The co-founders continue to think of their company as a startup. “We still think of ourselves as a company that has its best years ahead. Only 1 percent of the value creation has happened so far,” says Bhal.

First Published: Sep 16, 2025, 14:56

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Sep 19, 2025 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)