Incyte: The right chemistry

Incyte has one cancer blockbuster, and it's got Wall Street banking on another. Its secret: Embracing an older age of pharma

Incyte CEO Hervé Hoppenot counts on bleeding-edge tech like this NMR spectrometer, used to see individual molecules, to help his company invent new medicines

Incyte CEO Hervé Hoppenot counts on bleeding-edge tech like this NMR spectrometer, used to see individual molecules, to help his company invent new medicines

Image: Jamel Toppin for ForbesSusan Waite, 48, still remembers hearing her disease’s name, myelofibrosis, for the first time five years ago. “You Google,” she says. “I know you’re not supposed to, but everybody does. And at the time the average life expectancy was two-and-a-half years.”

This rare cancer was turning her bone marrow, which produces blood cells, into scar tissue, leaving her anaemic. She had one child in high school and two more in college, and was so tired she’d gone from being a social butterfly to a person who goes to bed right after dinner. Her spleen was so enlarged with blood cells that it hurt and prevented her from eating. Then her doctor offered her a pill called Jakafi, manufactured by a Wilmington, Delaware, company called Incyte. She felt better in days. After dinner at a restaurant, she insisted her husband stay out with her to hear a band play. Her spleen shrank. “I was able to eat full meals again,” she says. “It was exciting.” Now? She’s still a bit anaemic, but she’s doing well. “I feel almost normal,” she says.

Jakafi has transformed Incyte into one of Wall Street’s favourite stocks and a perennial subject of takeover speculation—in part because of Jakafi’s efficacy and in part because of its list price ($11,587 a month, indefinitely, usually covered by insurance). Last year, Incyte had a net income of $104 million on sales of $1.1 billion, up by 1,496 percent and 47 percent from the prior year. Its shares have sextupled over the past five years, and it has a $25 billion market capitalisation.

Incyte’s secret has been to stick to the traditional work of large pharmaceutical companies even as other firms have chased bright, shiny new technologies. Incyte’s 1,000 employees still work mostly in Delaware, a stick-in-the-mud stance at a time when companies from drug giant Merck to biotech firm Alexion are setting up shop in Boston to be closer to the hot zones of biology research. But more than that, Incyte is focussed on the basic chemistry of making drug molecules, a part of the drug-discovery process that many larger companies increasingly outsource.

Incyte already has two follow-ups: An arthritis medicine being developed with Eli Lilly that is approved in Europe and will be filed by early 2018 with the US Food & Drug Administration (FDA), and a second cancer drug, for which investor excitement is reaching a fever pitch. Hervé Hoppenot, the 57-year-old Big Pharma veteran who took over as Incyte’s chief executive in 2014, says he sees the company playing a role in a transformation of the way the health care system treats cancer.

Incyte was born out of one of the great names of American business: DuPont. In June 2001, the chemicals giant decided to sell its pharma division to Bristol-Myers Squibb for $7.8 billion. During the four months it took to close the deal, the division’s chief executive, Paul Friedman, started looking for another job.

Friedman connected with Julian Baker, a well-known biotech hedge-fund investor. Baker had a stake in a company called Incyte, which sold genetic information to drug companies. At the turn of the century, there was a tulip bubble around gene data, allowing companies like Incyte, Celera Genomics and Millennium Pharmaceuticals to raise huge amounts of money. At the end of 2001, Incyte had $508 million in cash. The deal Baker and Friedman struck was this: Friedman would take over as Incyte’s CEO but would build his research lab not near Incyte’s Palo Alto, California, headquarters but in Wilmington, where DuPont was based.

Friedman immediately began poaching DuPont’s best scientists. “People didn’t want to go to work at Bristol-Myers Squibb,” says Friedman, who is now chief executive of Madrigal Pharmaceuticals in West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, but still serves on Incyte’s board. “They wanted to find a new venue to work.” Swamy Yeleswaram, one of Incyte’s researchers, remembers getting the call. Friedman opened with: “So, Swamy, are you coming to Incyte?” Yeleswaram recalls that Friedman was annoyed that he didn’t immediately say yes. Much of Incyte’s core team, including current chief scientist Reid Huber and key inventors of all of Incyte’s drugs, were recruited from DuPont.

Incyte’s gene database was supposed to help this team invent new drugs. It didn’t work out that way. But one gene patent (which later turned out to be invalid) did point them in the right direction, toward a protein involved in the immune system called Janus kinase 2 (JAK2). Initially they hoped a drug targeting it would be effective against the blood cancer multiple myeloma.

In 2005, as Incyte was preparing the drug for clinical trials, three papers were published, in Nature, Blood and the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), showing that mutations in the gene for JAK2 were a central cause in both myelofibrosis and a related disorder, polycythemia vera, which causes a thickening of the blood. Within a day, the team had changed their plans, deciding to explore the efficacy of their new drug on these diseases.

Then came another speed bump. There were issues with both the side-effect profile and the intellectual property surrounding Incyte’s original JAK2 inhibitor. Friedman gave his team a week to come up with an alternative, and they used another JAK2 drug they’d originally planned to develop as a topical cream. By 2007, the drug was in clinical trials. In 2010, results published in NEJM showed half the patients who took the drug saw their spleen volume reduced by 50 percent. The FDA demanded more data that proved patients felt better, too. The drug, now named Jakafi, was approved in November 2011. In its first full year, it generated $136 million in sales.

Friedman decided to step down when the drug hit the market. (Incyte’s main building in Delaware is now named after him.) Hoppenot, who grew up in Champagne, France, and rose through the ranks at French pharma Rhône-Poulenc Rorer, was selected to replace him. At the time, he was the head of oncology at the Swiss drug giant Novartis, which had snapped up the right to sell Jakafi outside the US. Hoppenot says he couldn’t resist the opportunity to build a company around this cancer drug.

In 2016, Hoppenot purchased the European division of Ariad Pharmaceuticals of Cambridge, Massachusetts, including the rights to another blood cancer drug, to build out a European sales operation for Incyte’s future drugs. This past April, a rheumatoid arthritis drug Incyte had licensed to Eli Lilly was rejected by the FDA in a surprise to investors, Lilly said in August it would be able to resubmit the drug by January 2018.

Many of investors’ hopes for Incyte are riding on a new medicine, epacadostat, invented by Incyte’s in-house team. It is the brainchild of biologist Peggy Scherle, another recruit from DuPont. She became fascinated by a chemical pathway used by the developing foetus to protect itself from its mother’s immune system. Tumours apparently hijack the pathway to protect themselves. Incyte’s chemists tested 10,000 potential drugs to find one that could hit Scherle’s proposed target. Even then, it didn’t shrink tumour cells in the lab it merely kept them from growing.

But epacadostat seems to amplify the potency of two drugs made by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Merck: Opdivo (2016 sales: $3.8 billion) and Keytruda (2016 sales: $1.4 billion), both of which release the immune system to attack tumours. In clinical studies of the advanced form of the deadly skin cancer melanoma, patients seem to be more likely to see their tumours disappear with a combination of epacadostat and one of these drugs. A big Merck trial comparing the combination of Keytruda and epacadostat for melanoma will be completed in the first half of 2018. Even Roger Perlmutter, Merck’s head of R&D, is nervous. He thinks the trial will be successful but notes that no study has compared the combination of Keytruda and epacadostat with Keytruda and a placebo. “All the arguments now are from single-arm data with historical reference,” he warns. “That could turn out to be wrong.”

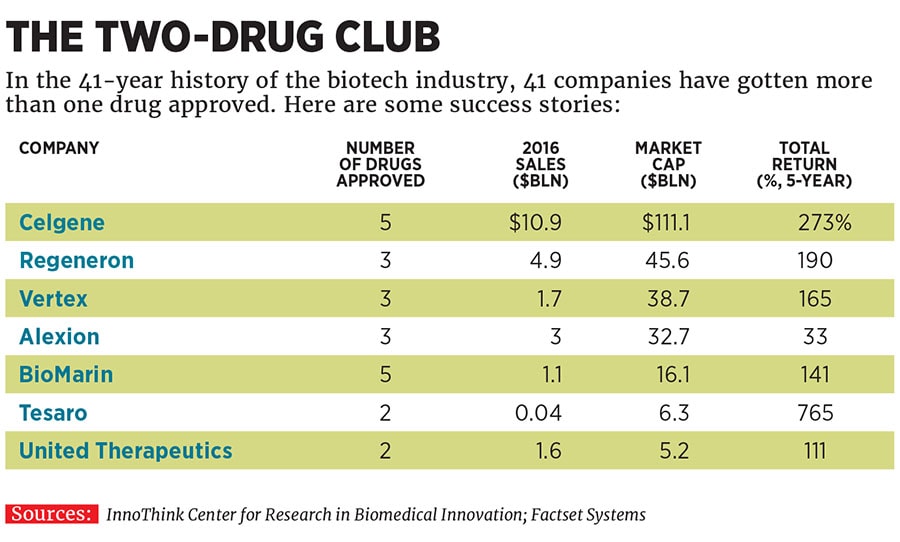

Incyte’s executives note that the epacadostat results have been consistent across studies in melanoma and lung cancer. If it does work, it will make Incyte one of the lucky few companies selling multiple blockbuster cancer drugs (see table), which fetch a high price on the US market. Hoppenot says that the US system can be “illogical and cruel”, forcing huge co-payments on patients for the drugs most likely to save lives, but insists that his drugs will be good for the health care system. He compares the revolution in cancer to the one that happened with HIV two decades ago, saying that drugs like the ones he has worked on at Incyte and Novartis will cost a lot but will justify themselves by emptying hospital wards. That would be a wonderful thing.

First Published: Nov 27, 2017, 07:41

Subscribe Now