Bharat Forge Bets Big on Defence: How Baba Kalyani is powering India's military

As India shifts from the world's top arms importer to a rising exporter, Bharat Forge is seizing the moment with artillery, drones, and cutting-edge tech

There are days when 76-year-old Baba Kalyani wishes he was younger.

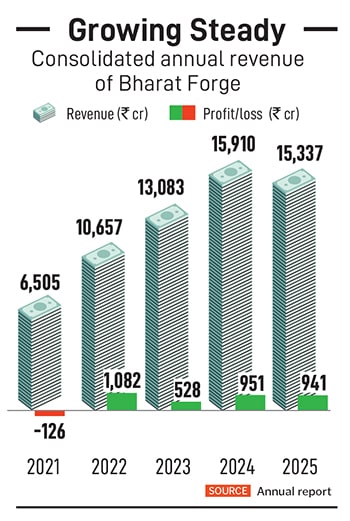

Kalyani is India’s 66th richest man, worth $3.9 billion, according to the 2025 Forbes World’s Billionaires List. The Kalyani group, of which he is chairman, includes Bharat Forge, India’s largest automotive component maker.

Yet, he is wistful.

“I wish I was 25 or 30 years younger," Kalyani tells Forbes India at Bharat Forge’s headquarters in Pune. “I could have done wonders."

Because of the people and their brain power.

“The young people today, especially those who have studied in good institutes, have tremendous brain power. The ecosystem is also fast developing. Had this ecosystem existed 25 or 30 years ago, it would have been amazing."

As if to make up for the lost time, Kalyani is a man in a hurry, rapidly opening newer frontiers. A swashbuckling office at Bharat Forge is dedicated to robotics and humanoids, hiring young graduates from top-tier engineering colleges in the country. The group has set up five verticals: Auto components, aerospace, industrial goods, electric vehicles (EV) and defence.

It is the fifth vertical, defence, under which Bharat Forge manufactures everything from protected vehicles to artillery and ammunition and tanks, that is redefining the group and preparing it for its next phase of growth. In Kalyani’s assessment, the defence vertical will likely eclipse Bharat Forge’s core auto components business as the largest in the group in terms of revenue. Bharat Forge has established a subsidiary, Kalyani Strategic Systems Limited, to focus on the defence business.

His son Amit, vice chairman and joint managing director of Bharat Forge, says: “We spun it off into a new company because that has its own cadence, requirements, technology, customer bases, and it is largely a business-to-government segment."

There is good reason for that.

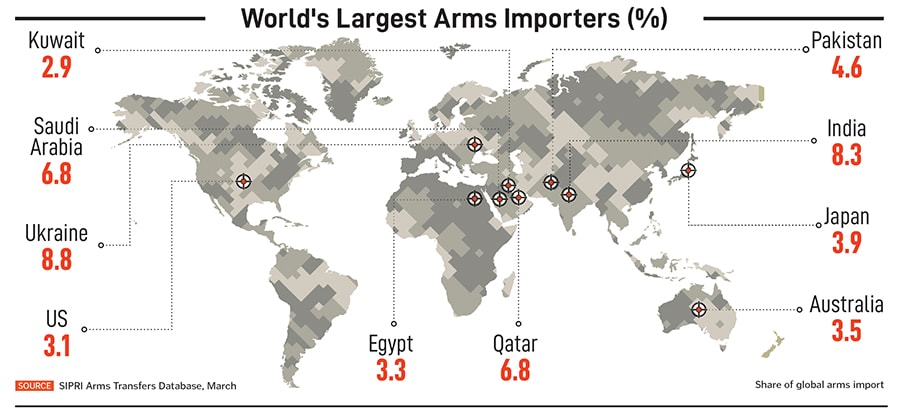

India has always been among the biggest importers of weapon systems. At present, it is the second largest, next only to the war-ravaged Ukraine. That must be seen against the backdrop of defence manufacturing in the country for decades being confined to public sector companies and ordnance boards—the latter were not even companies but more like government departments without balance sheets.

In May 2001, the government opened the defence sector to private companies with up to 100 percent participation. That started a trickle of private sector companies coming in which, over the years, turned into a torrent. The flow increased after 2023, with the government deciding to set up two defence industrial corridors, one each in Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. The corridors are meant to boost domestic production, streamline regulations, and promote collaborations among private and public sector companies as well as with international entities.

The opening up of the sector came with other decisions, among which the more potent one is that 75 percent of the orders placed by the armed forces must go to the domestic industry. Along the way, ordnance boards were corporatised.

As a result, though large public sectors giants such as Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd, Bharat Electronics, BEML (formerly Bharat Earth Movers Limited) and others continue to hold considerable sway, an array of big private sector names is now making defence systems. These include the Tata Group, Mahindra & Mahindra, Ashok Leyland, and Larsen & Toubro—in addition, of course, to Bharat Forge. That is not all there is a bevy of small enterprises and no less than 600 startups trying to do their bit in defence.

By most accounts, the private sector has come to comprise nearly a quarter of the country’s defence manufacturing.

All this, and more, manifested itself during Operation Sindoor. During India’s brief war with Pakistan in May, to avenge the Pahalgam terror attack, made-in-India defence equipment was seen to play a visible and decisive role. “The weapons made in India played a major role in reducing terrorist hideouts to rubble," Prime Minister Narendra Modi said on July 26. “Weapons made in India are still keeping the masters of terrorism awake at night."

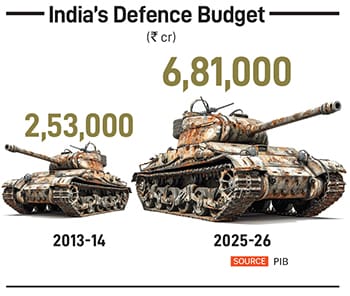

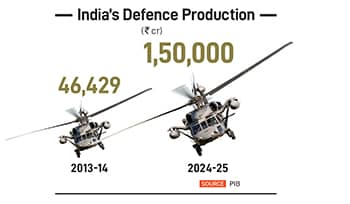

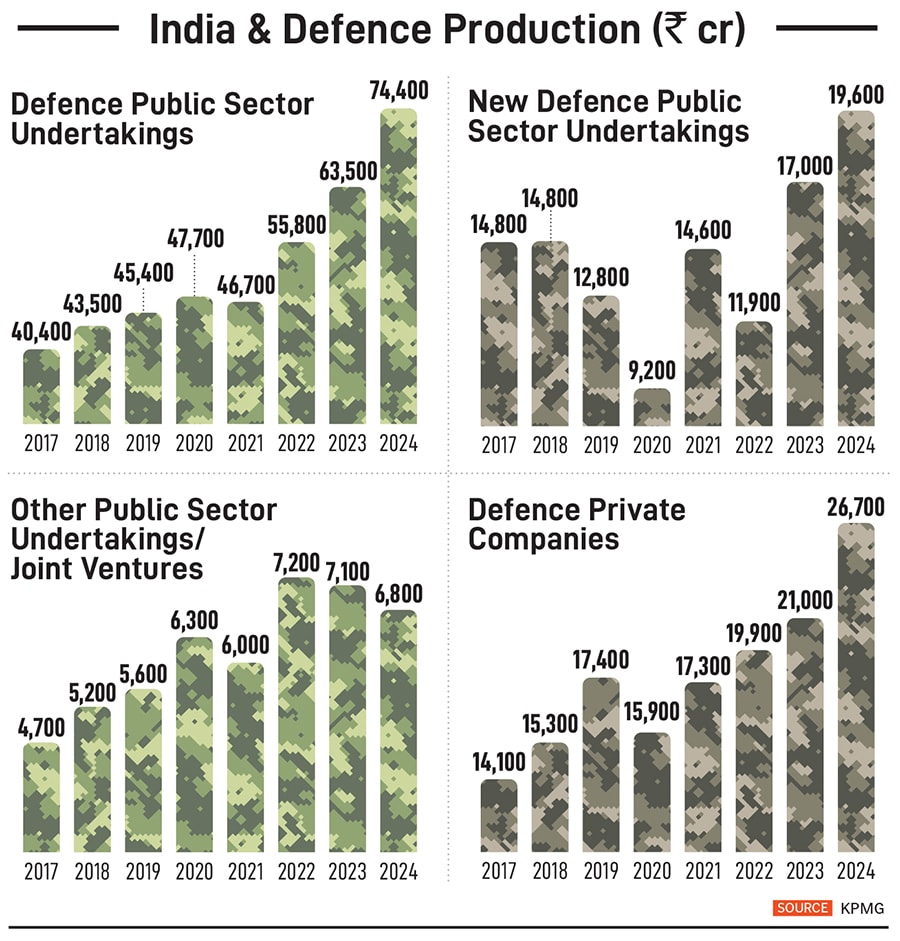

The defence industry’s role is not limited to one skirmish or the needs of only the Indian military. In 2025, defence production increased by 224 percent to ₹1.5 lakh crore from approximately ₹46,429 crore in 2015. Importantly, exports exceeded ₹23,500 crore, up 30 times in a decade.

Besides, India’s stated position is that Operation Sindoor is not over, merely on a pause. There is widespread expectation that Indian armed forces will be doing a lot of purchases and that the defence budget might rise above the 1.9 percent of gross domestic product as in the last Union Budget. Already, the defence ministry has opened a round of emergency purchases, which require fewer clearances.

“Historically, India relied heavily on foreign countries for its defence needs, with about 65 to 70 percent of defence equipment being imported," consultancy firm KPMG said in a report published in May. “During FY24-25, the Ministry of Defence signed a record 193 contracts worth over ₹209,050 crore, of which 177 contracts, or 92 percent of the total, were awarded to the domestic industry. Additionally, India’s imports decreased by 9.3 percent between 2015-19 and 2020-24."

No wonder, at the time this story was being finalised, the defence index of the National Stock Exchange, which has 18 companies, was at 7,800 on August 7, much higher than its 52-week low of 5,129 in February.

“In light of the evolving geopolitical and strategic landscape, the importance of import substitution for subsystems and components, as well as minimising external dependencies, has become increasingly significant," says Abhijit Apsingikar, senior defence analyst at London-based consultancy firm GlobalData. “Bharat Forge, along with other Indian companies, must place a strong emphasis on developing alternative supply chains to mitigate the risk of supply disruptions in the near future."

Kalyani studied at the Rashtriya Military School, Belgaum. “Many of my classmates retired as Generals and Air Marshals," he says. “Naturally, I have an affinity for things that are connected with the armed forces."

It wasn’t until 2010, though, when Bharat Forge was generating annual sales of more than $1 billion and had taken the lead in the country’s auto component manufacturing, that Kalyani decided to foray into the defence sector. Back then, the defence industry was taking baby steps towards setting up manufacturing facilities after decades of government control.

“There was no policy to make it happen," Kalyani says. “One day, a thought occurred to me. We are a forging and metallurgical company. All the artillery guns are forgings. The ordnance and barrel of a gun is forgings. So, I made the barrel for the Bofors gun, which was then made by the ordnance factories. That is how we started."

That was followed by the barrels for the T-55 tanks, a Soviet-made tank, and then the barrels for the T-72 tanks. The watershed moment came in 2012, when the Indian government held the Defence Expo in New Delhi, where Bharat Forge showcased its 155mm/52-calibre gun.

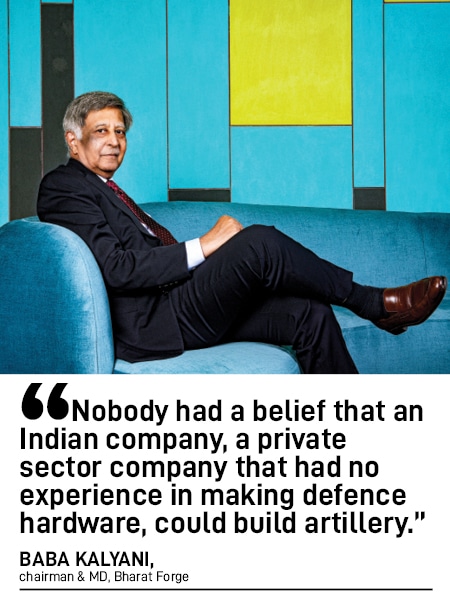

“We were probably the only Indian company that had shown full equipment at that time," Kalyani recalls. “Nobody had a belief that an Indian company, a private sector company that had no experience in making defence hardware, could build artillery."

That paved the way for Bharat Forge to be selected alongside Tata Advanced Systems Limited (TASL) in 2013 by India’s Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) for building the Advanced Towed Artillery Gun System (ATAGS) Howitzer. The DRDO is the defence R&D arm of the government.

It took more than 12 years to finally sign contracts for the procurement of 307 ATAGS 155mm/52 calibre guns and 327 high-mobility 6x6 gun towing vehicles, at a cost of around ₹6,900 crore, from Bharat Forge and TASL. That order, approved earlier this year, marked the first major artillery purchase since the 1987 Bofors deal.

In 2011, Kalyani was on a visit to the Cranfield University in the United Kingdom, the only university with a strategic relationship with the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL), the equivalent of India’s DRDO. In display at the university were artillery guns from across the world, made over the past 40 years. Kalyani met a professor, the head of the artillery division.

The professor told Kalyani of an artillery manufacturing plant being sold in Switzerland. “I saw the equipment list on the internet, and it was very interesting," Kalyani says. The next day, he was in Switzerland to meet the managing director of the plant being sold by RUAG (Rà¼stungsunternehmen Aktiengesellschaft Armaments Companies). “He said, ‘You can take everything that is here, but you won’t get any technical papers or technical details, any manufacturing process. That is your job’."

Kalyani signed a contract for 1.7 million Swiss francs to acquire the assets. Over the next few months, he sent engineers from Bharat Forge to disassemble the equipment and bring them to India. “Within a year, we had a complete plant to make artillery guns," Kalyani says. “Then we started putting the plant in production and started learning the processes because we had no knowledge of the processes. We tried to get people who had retired from the ordnance factories, and they made things happen in a short period of time."

From 2014, the tide began to turn, thanks to Prime Minister Modi’s Make in India programme to enhance manufacturing in the country. “He clearly understood that this is one area where India needs to get self-sufficient, because if you don’t get self-sufficient, and especially in periods like we are seeing today, anybody can choke you," says Kalyani.

The government soon introduced a change in policy for defence production, which has since been revised multiple times to allow for greater domestic participation. The new policy allowed licences to be in place within 15 days, compared to the long periods required earlier. “In the old days, you used to have a licence that was valid for one year," Kalyani says. “So, if you did not produce for one year, the licence lapsed. Defence is not a product that can be made in one year. The new government gave a perpetual licence."

Manohar Parrikar, who was the defence minister from 2014 to 2017, revised policies to allow the private sector to use defence facilities in the country to test their weapons, which was not allowed earlier, in addition to making the application process seamless. “So now you had a policy that was in place, you had ranges that got opened up," Kalyani says.

This was followed by the government’s decision to launch a revamped Defence Procurement Procedure (DPP) 2016, which was first introduced in 2013. The new policy introduced a Buy IDDM (Indian designed, developed, and manufactured) category and a refined “Make" procedure, under which the government funded part of the expenditure.

“Before 2020, India’s defence procurement was predominantly managed by defence PSUs, with the production of weapon systems, platforms and subsystems being strictly regulated," adds Apsingikar. “However, the reformed Defense Acquisition Procedure (DAP) enacted in 2020 opened the door for increased participation of the Indian private sector in the procurement of IDDM products."

Still, there are challenges, particularly in the domestic acquisition process. Take, for instance, the ATAGS. It went into development in 2013, but Bharat Forge received a firm order only this March. “In the meantime, we exported ATAGS to Europe last year," Kalyani says. Last year, Bharat Forge exported 100 guns, including 18 ATAGS, to countries in Europe, signalling the growing opportunity for exports. Europe, South Asia and Africa are considered potential markets for Indian-made defence systems.

The private sector, while vying for contracts, often finds itself up against PSU behemoths. “The Defence Public Sector Units (DPSUs) are privileged for defence contracts, especially for large high-risk projects," says Kartik Bommakanti, senior fellow at public policy think tank, Observer Research Foundation. “Consequently, contractual arrangements are not stable for the private sector, as opposed to the DPSUs, which have a steady revenue stream."

Bharat Forge is ploughing money into R&D. Its defence vertical, apart from artillery guns, has begun focusing on electronics, which are essential for unmanned systems, armoured vehicles, small arms, and underwater systems.

The Kalyani group has a joint venture with the Israeli state-owned Rafael Advanced Defence Systems to manufacture defence systems, including anti-tank guided missiles such as the Spike. Last year, Kalyani Strategic Systems acquired a 25 percent stake in Italian design company EdgeLab SpA, which specialises in the design and manufacture of Autonomous Underwater Vehicles.

Now, Bharat Forge is considering joining a consortium of Indian defence manufacturers to bid for making India’s indigenous fifth-generation stealth fighter, the Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA). In May, the government allowed the private sector to participate in this, alongside HAL. AMCA is a single-seat, twin-engine, all-weather, multi-role combat aircraft.

The company is also focusing on drones and unmanned aerial vehicles, as the art of global warfare witnesses a rapid shift. In June, for instance, Ukraine launched Operation Spiderweb, a covert drone attack deep inside Russia, which was the largest drone attack on Russian air bases. Drones were also used heavily during the India-Pakistan conflict in May.

“Although we have been making drones here for the last five years, their importance has gone up after Operation Sindoor and the Russia-Ukraine conflict," Kalyani says. India has fast-tracked the procurement of 87 Medium Altitude Long Endurance (MALE) drones for its armed forces, valued at ₹20,000 crore, for which Bharat Forge is gearing up to bid.

Meanwhile, the Kalyani Group is laying the foundations for a diversified business. That programme is often referred to as Bharat Forge 2.0. Much of that decision followed the Covid-19 pandemic, which caused supply chain disruptions around the globe.

“Bharat Forge 2.0 looks at our business holistically," says Amit. “Prior to that, we had the automotive business and the non-automotive business. And we thought many of the non-automotive businesses were getting a step-brotherly treatment. We thought about how to create a sharper focus on different customer segments and technologies. We knew that by just doing forgings, we were not going to be able to grow beyond a certain point."

Today, an aerospace vertical manufactures gas turbine engines, aero-frames, landing gear and critical engine components. The industrial business recently acquired Coimbatore-based JS Autocast Foundry India, which supplies critical machined ductile iron castings for wind, hydraulic, off-highway, and automotive applications. The division also makes forging components for wind and gas turbines.

“Over the last decade, Bharat Forge has developed new frontiers for growing beyond its core business, with investments in capabilities and capacities in place," brokerage firm Motilal Oswal said in a report in May. “The majority of Bharat Forge’s core segments, auto (both domestic and exports) and select industrials businesses, are currently witnessing a demand slowdown. Given this backdrop, its defence, JS Auto Cast, and aerospace segments are likely to be the growth pillars in the near term."

The core auto component business, meanwhile, contributes approximately 56 percent of the group’s revenues, down from 80 percent in 2007. “We are still strong in our fundamental business," Kalyani says. “But whether it is India or outside, the automotive industry is not doing very well. Sixty percent of exports today are destined for the US and Europe. Now, with US President Donald Trump’s tariffs, we do not know how supply chains will change."

The group has an e-mobility arm that provides EV solutions, ranging from sub-systems to complete electric powertrain kits. “The e-mobility business has been the slowest to take off because the EV market in India is largely passenger cars," Amit says. “It is platform technologies that have been developed by the OEMs through their own engineering efforts, either in India or in partnership with global companies."

The defence business, though, could be looking at growth of three to four times from ₹1,700 crore in the next four years. “I never looked at defence as risk capital," Kalyani says. “It was just passion. In our defence business, everything is designed by us. Every IP (intellectual property) is owned by us. And, therefore, we are able to export. Nobody else is able to export because they don’t own the IP."

With the defence sector finally showing signs of coming of age, it is natural that Kalyani would want to be 25 or 30 years younger. And the boy from Rashtriya Military School, Belgaum, would be loving every bit of it.

First Published: Aug 20, 2025, 14:25

Subscribe Now