A brief history of ghee in the US

America's taste for 'clarified butter' predates its love affair with it as a super-food by well over a century

Jonathan Franzen’s new novel, Purity, has a tiny smear of ghee on Page 37. The young Californian protagonist, Pip Tyler, asks three female colleagues, who are about to set off on their evening jog, if they have “a good recipe for vegan cake with whole-grain flour and not too much sugar”. At first they look stupefied, and then a comical conversation follows:

“Is butter vegan?” the third said.

“No, it’s animal,” the first said.

“But ghee. Isn’t ghee just fat with

no milk solids?”

“Animal fat, animal fat.”

“OK, thank you,” Pip said. “Have

a good run.”

It’s typical of Franzen, one of America’s shrewdest social novelists, to slip in this reference to a food that most Americans are unaware of but which has begun to attract a strong niche following. In the US, ghee is trending. Especially among millennial foodies smitten with super-foods like quinoa and kale, fair-trade organic produce, and Bulletproof Coffee, which is coffee blended with butter (or ghee) and a spoonful of coconut oil extract. It sounds expensive and ghastly, but it’s all the rage. At the hip new Bulletproof Coffee Café in Santa Monica, California, you can add ghee to your coffee for a dollar.

Ghee has also received a big boost from the Paleo diet, the latest food fad in the house, whose startling No. 1 guideline is that “a Paleo diet should be high in fat”. It provides recipes for ghee flavoured with garlic, ginger, mint-jalapeno and rosemary-thyme. Elsewhere, Michelin-starred restaurants advertise the use of ghee in their curries, and on Twitter, celebrity chef Alton Brown instructs his million-plus followers on the deceptively simple art of making it: “Do you know how to make clarified butter? Or know what ghee is? We’re big fans of both…,” he writes, embedding a link to a recipe.

Less well known is that the relationship between the US and ghee dates back to well over a century. Perhaps the earliest mention of ghee in American literature occurs in an 1831 Edgar Allan Poe short story, MS Found in a Bottle, which describes a trading ship in Java carrying “coir, jaggeree, ghee, cocoa-nuts, and a few cases of opium”. Another stray mention pops up in an 1895 letter Mark Twain wrote to Rudyard Kipling as he prepared to embark on a world tour that included a stop in India. Twain playfully commanded Kipling to “be on hand with a few bottles of ghee for I shall be thirsty”.

The first meaningful culinary mention of ghee is probably an 1863 recipe for “A Sinee Kabaub” in Godey’s Lady’s Book, the most popular magazine of the Civil War era. A neat illustration of chunks of beef threaded on a skewer (the concept of the kebab was also new) was accompanied by instructions to strew the meat with “a small quantity of fine curry-powder” and “expose the same before a clear, fierce charcoal fire, basting the whole with a bunch of fowls’ feathers introduced into fresh ghee till done brown”. At the bottom were instructions on how to make ghee.

What is unusual about this recipe is that it uses the word ghee instead of clarified butter. Civil war food historian Helen Veit says that she doesn’t remember seeing “ghee” in any 19th-century cookbook. “But then I realised that I’ve seen all sorts of 19th-century recipes calling for clarified butter,” she told ForbesLife India, “in recipes for fried eels, potted pigeon and sautéed bananas. Several recipes called for poaching eggs in a deep pan of swirling hot clarified butter—apparently the eggs came out buttery and as round as balls.”

By the early 20th century, larger groups of Indian immigrants—mainly seamen and students—had begun to arrive in New York, bringing their foods with them. The 1911 Grocer’s Encyclopedia published in New York City, which listed all sorts of exotic immigrant food, had an entry for ghee along with canned kangaroo tails, wasabi, brie, and penguin eggs. One of the most striking mentions of vegetable ghee or vanaspathi is to be found in Chains to Lose, the memoirs of Dada Khan, a resourceful seaman and freedom fighter who arrived illegally in the US and jumped ship in 1918. He records how he crawled through a duct of the ship to steal onions and potatoes from the storage area, and cooked them in spices and “vegetable ghee”.

By 1913, New York had its first restaurant serving Indian food.

The second and most bizarre chapter of the American ghee story unfolds in the 1950s. When the government found that dairy farmers were swimming in 260 million pounds of surplus butter, they floated a strange idea: Why not turn all that butter into ghee and sell it in India? A market was guaranteed, for, as one report stated: “Ghee is more a part of everyday life in India than the sandwich is in America.”

When about 30 firms expressed an interest in making ghee for the eastern markets, the US Department of Agriculture dispatched a dairy expert named Louis H Burgwald to India. Burgwald spent three weeks getting merchants to taste his samples of American ghee. The first lesson he learnt was there was no one ghee to fit all tastes. Calcutta and Madras liked cow ghee cooked at a high heat, while Bombay preferred buffalo ghee cooked at a low heat. Calcutta scorned Bombay ghee as raw and Bombay dismissed Calcutta ghee as burned. If these regional needs could be catered to, said an optimistic Burgwald, there was a good chance of exporting ghee to India. He then headed to Pakistan and Egypt, two other ghee-eating nations, before returning to the US, where newspaper headlines in May 1955 declared: “India to Import 500 tons of American Ghee.”

Eventually nothing really came of this grand plan but it had one delightful outcome. The New York Times commissioned RK Narayan in Mysore to write “a treatise for Westerners on what ghee is”. As one of India’s leading writers, Narayan was an obvious choice, but what the Times probably didn’t know was that the initial R in his name stood for Rasipuram, a town in Tamil Nadu known for its fragrant ghee. Narayan’s piece, enlivened by tart asides and gentle humour, was titled “Ghee is for Good”, which made no sense unless ghee was mispronounced as G. The subtitle explained, “Pronounced Gee, this butter product evokes that response in India.”

“A more improbable combination than ghee and the United States cannot be easily imagined,” Narayan wrote. “In one’s mind, the former was as far away from the latter as Everest from Niagara.” But since ghee was building bridges between the two countries, he continued, we “respect those who offer us a supply of this good stuff”.

He went on to grapple with that dreaded question the non-ghee native asks: What is ghee? “Ghee is, no doubt, clarified butter,” wrote Narayan, “but it is also something more, in the same way that wine is more than the juice of a squeezed grape. The origin of ghee is, no doubt, butter, but ghee is like a genius born to a dull parent… A perfectly boiled ghee is considered fit for the gods.” Ghee, he said, was a litmus test of integrity: One could measure the morals of a shopkeeper or the fine qualities of a host by the purity of ghee offered. Pure ghee, he said, “must be slightly yellow in colour and when solidified have the granulation of sand”. He concluded by crowning ghee with the ultimate superlative: “If I were asked to mention any single achievement of our country, I’d say it is the discovery of the process of changing butter into ghee.”

New Yorkers must have been terribly curious about this elixir that provoked such profound reverence in the writer. But at least some of them would have come across ghee in the glossary of Kamala Markandaya’s best-selling 1954 rural novel, Nectar in a Sieve. Many more would have grown up reading about “ghi” in the hugely popular children’s story The Story of Little Black Sambo. Written and illustrated in 1899 by Helen Bannerman, an Englishwoman whose husband was posted in India, the story revolves around an African boy’s adventure in an Indian jungle. Though terrified at being confronted with tigers, he keeps calm. It all ends well with the tigers dissolving into “a great big pool of melted butter (or ‘ghi’, as it is called in India) round the foot of the tree”. His father Jumbo scoops up the ghee and mother Mumbo uses it to make pancakes. For decades, the book was a library favourite, until the post-Civil Rights era of the 1970s, when concerted attention was drawn to the offensive name “Sambo” (a pejorative for Black children), as well the parents’ names and the caricatured illustrations, leading to calls for a ban. Sambo was subsequently revised into politically correct versions, with the boy’s named changed to Babaji or Sam.

Image: Indian immigrants- Getty Images

Clockwise from extreme left: As groups of Indian immigrants arrived in New York, ghee made its entry into the 1911 Grocer’s Encyclopedia Ancient Organics is an artisanal California company that boils its ghee on full-moon nights Sandeep Agarwal of Pure Indian Foods quit Wall Street to make shuddh ghee in New JerseyStarting from the 1960s, ghee has been stuck with an unhealthy tag and blamed for being an artery-clogging killer. In the last few years, however, ghee-makers and chefs have pushed back against that outdated judgment. At the vanguard of this gheevangelism are artisanal outfits making organic ghee in small handmade batches from the butter of grass-fed cows. Companies like Sandeep Agarwal’s Pure Indian Foods—which got Paleo to endorse ghee—and Ancient Organics charge twice as much as non-organic brands like Amul (the biggest ghee retailer in America), Swad, Deep and Laxmi. Both companies say the bulk of their consumers are not Indian-American, who prefer to stick to the brands listed above.

Sandeep Agarwal quit Wall Street and joined forces with his wife to make shuddh ghee in New Jersey. “We work with farmers who have organic cows,” he says. “I personally go and check if the cows are eating grass. Initially, we had to hire professional nutritionists to educate people about ghee. We had YouTube videos and I did a lot of demos at Whole Foods handing out samples and talking about its high smoking point. To explain what ghee was, we told people it tastes like movie-theatre popcorn.”

Eight years later, Pure Indian Foods is among the best-selling organic ghee brands on Amazon and available at Whole Foods stores in New York, New Jersey and Maryland. “We did not reach out to all the Whole Foods because we don’t make enough ghee,” says Agarwal. “My wife Nalini makes all the ghee herself on full-moon nights. It’s an art she knows instinctively when it’s done, so that the ghee is neither underdone nor burnt. I joke that the only way for us to make more ghee is for me to have many wives.”

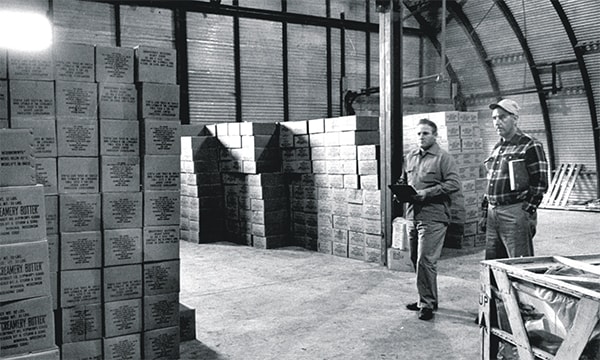

Image: Getty Images

Surplus butter stocks in the US in the 1950s led to plans of American ghee being exported to India. Nothing much came of itOn the other coast in California, Chief Gheewallah at Ancient Organics, Matteo Girard Maxon, also boils his ghee on an open flame on full-moon nights to the accompaniment of the Mahamrityunjaya mantra. “Americans have no idea what ghee is, and are very confused around fats,” says Maxon, who practices ayurveda. “Ghee is predominantly saturated fat, which is good fat.”

Over the last six years, demand had steadily climbed. “We’ve received a huge amount of attention after Bulletproof Coffee and the Paleo diet,” says Maxon. “I meet people who say, ‘I’ve heard of ghee, it’s what you put in Bulletproof Coffee.’ They have no idea, no context of this ancient cooking oil. On Amazon, we found lots of people googling for organic ghee and grass-fed ghee. Our main customers are women. There are enough people peppered all over the country to make for a strong online ghee market.”

Americans use ghee quite differently from the way it is used in traditional Indian cooking. People use it to sauté asparagus, pan-sear a chicken breast or poach salmon they drizzle it over lobsters or stir a spoonful into their morning oatmeal.

The website of OMGhee, a new organic ghee company in New Jersey run by two friends, Mitul Parekh and Simon Bennett, buzzes with recipes for everything from ghee zoodles (zucchini noodles) to ghee tacos. “About three years ago, I saw that ghee was high on the list of many nutritionists and athletes but no one knew where to get it or how to use it,” says Parekh. “I felt there was an opportunity to take ghee to a broader audience. In order to showcase its versatility, we show how it can be used in everything from Indian food to steak and potatoes to pasta.” Recipes are liked and tweeted by their followers, known as— what else—but #gheeks.

First Published: Dec 19, 2015, 06:45

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Sep 10, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)