A startup’s strength is the freedom to explore: Pawan Goenka

The IN-SPACe chairperson on bridging ISRO and startups, governing as an outsider, and why failure tolerance is the key for building India's private space ambitions

As founding chairperson of IN-SPACe, Pawan Goenka is helping to architect the bridge between the legacy of the Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro) and India’s growing private space ecosystem. In an interview with Forbes India, he reflects on why coming in as an “outsider” was his biggest strength, how the government works behind the scenes and why tolerance for failure is essential for building a global space power. Edited excerpts:

Q. It’s quite a shift from leading Mahindra to building a new space governance institution. When you made that move, did you know what you wanted to accomplish?

My answer might surprise you. When I was asked to take on this position, I had no clue about the space sector other than what you read as an interested layperson. Post my retirement, I had been doing some work with Minister Piyush Goyal on an MSME (Ministry of Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises) committee, so I had some exposure to government. Earlier, in my automotive days, through SIAM (Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers) and similar bodies, I had a lot of engagement with the government. So that’s how, perhaps, the government knew of me.

Q. What convinced you to take up the offer?

The offer came out of the blue, and I debated whether I should accept it. Then I was told that my biggest strength was precisely that I knew nothing about the space sector—but I did know about technology. I knew how to grow a business, what makes a company succeed, and of course, I understood R&D (research and development). They said they wanted someone who was not biased by the legacy of space, but who understood what needed to be done to make the private sector succeed in space. That’s how I came in.

Q. How did you onboard yourself into the ecosystem?

I did it simply by visiting all the Isro locations, talking to people there. I read about space technology, went into the history of what had happened in India, and, at the age of 67, I became a basic student again.

Q. As you immersed yourself in this new world, what stood out to you the most about India’s space capabilities and institutions?

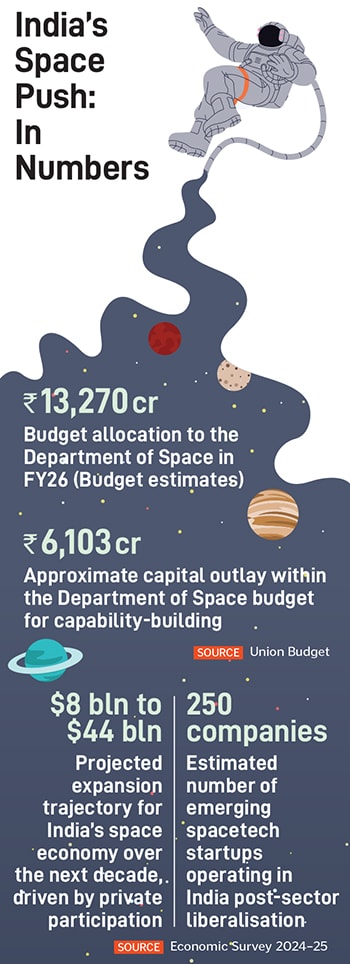

What surprised me was how deep Isro is in terms of technology and infrastructure. People at Isro understand space technology very well, and they are able to work with limited resources, because Isro’s budget is about Rs13,000 crore—around $1.5 billion—compared with the multiple tens of billions that agencies like NASA have. Yet Isro delivers a great deal.

The second surprise is how hard people in government work. The norm is people starting at 8 am and working till 10 pm, seven days a week. The term ‘work-life balance’, which is so popular in the corporate sector, is unheard of in government.

The third surprise was the process orientation in government. It’s better than that of any corporate I can think of. For everything, there is a defined process.

Q. How is the process and accountability in government different from running a large, listed company, structurally and culturally?

Running a government and running a big company are two different cups of tea. As CEO of Mahindra & Mahindra, I was responsible to a few lakh shareholders. As prime minister of India, you are responsible to 140 crore people. Any one of those 140 crore people can question you. If the government didn’t have those processes, it would become chaos.

Q. How did you shape IN-SPACe?

IN-SPACe itself is a startup and I’m employee number one. We started with 10 to 15 people, then 20, 30, 40… we’re a startup, which means we are defining our own path.

A startup’s strength is the freedom to explore, to fall down and not get beaten down for it, to get up and walk in a different direction if needed. The government cannot give the same extreme freedom, or everything would be chaotic, but there is enough freedom if you are willing to work within the system and push constructively.

For example, nobody told us we had to create a 10-year, $44 billion vision for the sector. Nobody told us we had to design particular schemes, or undertake technology transfer in the way we are doing. Nobody told us we had to set up the kind of skill development initiatives we’ve started. None of that is written in any booklet. These are all things we created over time.

Q. What kind of leadership and team did you feel IN-SPACe needed?

In a small organisation like IN-SPACe, a lot depends on the leadership team, and leadership does make a huge difference. That’s perhaps why the government went outside to get someone they thought could do this job well.

And I was very lucky with the people I was able to get from Isro in the first round of hiring. The-then Isro Chairman S Somanath was part of the interview panel for the senior people, along with me. He made sure I got the right people. Without that set of people, we wouldn’t have been able to do what we’ve done. Many of them are close to retirement and had never done this kind of work in their lives. So, the transition was not easy, but they all did extremely well.

We are a small group of 46 people now with a management team of five. We are constantly in dialogue about what is working, what is not, what companies are telling us and what we should do next.

Q. What is the strategic intent behind the Rs1,000 crore venture capital fund, and how do you see it working?

This is not a grant; it is a pool of money the government has set aside to invest in space. It will be invested like any other venture capital fund—by examining the business plan, the probability of success and the expected return.

The funds are clearly meant to help space startups by providing a dedicated channel of funding. This fund is focussed on the space sector, so its money has to go only to space companies. We’ve defined some parameters for that.

Importantly, IN-SPACe will not decide who gets the money. We will have no role in individual investment decisions. The fund manager will decide.

Q. What is IN-SPACe’s role once the fund is operational?

The first role is giving the money —being the investor. It is important that we, as the investor, do not influence who the fund invests in. We may offer some inputs for technical evaluation, but we will not drive decisions.

There will be a dedicated fund manager for this fund, with a team that does the work. There is a technical advisory committee and an investment committee; the investment committee must approve investments. Then there are trustees. In a sense, the fund manager reports to the trustees.

When we sign the agreement as an investor, we set expectations for returns, just as in the normal venture capital industry. It’s not different.

Q. Can a Rs1,000-crore fund (approximately $120 million) truly move the needle for India’s space startups?

By itself, $120 million is not enough to move the needle. But we are expecting a multiplier effect. We become the anchor investor in many such deals, and that anchor investment motivates others to invest.

Most investors will do their own due diligence, of course, but our participation becomes a sort of mark of approval.

Q. Where is demand for Indian space capabilities coming from today?

You can put suppliers into two buckets and buyers into three. For vendors, there is a large opportunity to get demand from outside India. There are at least 300 medium-sized vendors with good capability who need to sell their capabilities globally.

For government demand beyond Isro, the focus is not vendors but new-age companies. Upstream demand will primarily come from strategic users who need satellites launched for specific requirements. Other government departments will focus on data and applications.

The third source is the non-space industry in India using space technology in their business. Here, we have more work to do. For IN-SPACe now, the number one priority is: How do we generate demand?

Q. How can traditional sectors plug into space-based data and services?

A lot of decisions currently taken manually can be supported by space-based data and analytics. Fishing is a good example where, with space technology, accidents at sea—where boats drown or get into trouble—can be reduced. Another powerful application would be tracking potential fishing zones to find the best catch.

Agritech, maritime, mining, power—all these sectors can benefit. For mining, satellite data can help with understanding inventory and planning. Power utilities, including public sector units, can use it for identifying routes, planning transmission, monitoring corridors, and so on.

Right now, in aviation, we are also not using space-based communication and Internet of Things enough.

Q. What kind of bets do you think Indian spacetech founders should be making?

The beauty of startups is that they don’t know yet what doesn’t work. I know many things that don’t work; that can become a constraint.

Right now, our view is that we should not stop any startup even if there are ‘too many’. Not all will succeed, and even if they all do, the market will expand. However, where we find a gap, we intervene. If we find nobody is investing in a certain area, we will create schemes or incentives.

Q. That implies tolerance for failure. Is the system ready?

We are giving two kinds of money. One is investment through the venture capital fund. The other bucket is grants, where the licence to fail is explicit. When we give money, we don’t do it expecting failure. We choose people we think will succeed, but some will still fail. That’s the nature of innovation.

Q. In India’s space startup landscape, which problems are being tackled well today, and where are the big white spaces?

Startups succeed only if they are solving a problem better than existing solutions. Otherwise, there’s no uniqueness.

The problem being addressed well today is small satellites. In terms of launch vehicles, satellite manufacturing and the supporting ecosystem... quite a lot is happening. Today we can list a number of companies which are on their way to becoming global standards for satellite manufacturing. Many of our interventions are also oriented in that direction.

Q. On the global stage, what is India’s real edge beyond cost advantage?

Cost advantage cannot come at the cost of anything else. There is no space user who will buy from you just because you are cheaper, unless you are absolutely on par in quality and technology.

India’s advantage in space is that it is one of the very few technology sectors where India gets a seat at the head table globally. Isro’s failure rate for satellites is among the best in the world. That shows India has the capability and reliability.

The private sector must demonstrate the same quality. That’s why we are very cautious in approvals at IN-SPACe.

One thing I learnt in automotive is that if something fails in testing, it will fail in real life.

If we can maintain that quality, then the cost advantage will carry us far. Isro has set that stage. We are now aligning all the ducks.

First Published: Dec 24, 2025, 12:53

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Dec 26, 2025 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)