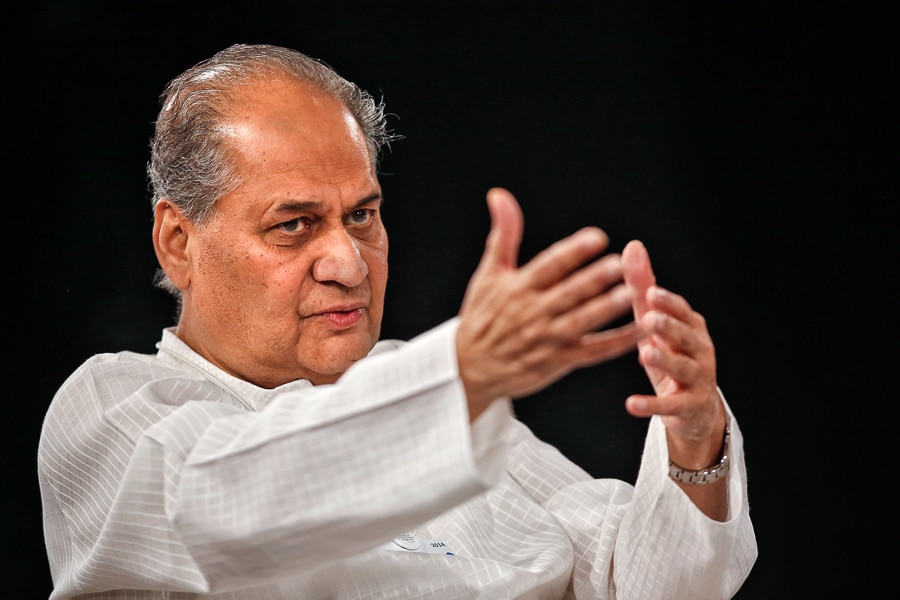

Rahul Bajaj: He punched, not below the belt

Most fights are fought to win, but Rahul Bajaj also fought a few because they needed to be fought

Image: Anindito Mukherjee/ Reuters

Image: Anindito Mukherjee/ Reuters

My first interaction with Rahul Bajaj in the early 90s was not a pleasant one. And I had only myself to blame. As a rookie sub-editor at a fortnightly business magazine trying to earn his spurs as a writer, I committed one of my first cardinal sins: Agreeing to write a cover story in a bid to snare an interview. There were a couple of problems with this route: One, as my editor drilled it in me subsequently—and as I do these days—you never promise a cover story even if it goes on to be one. The other problem was even though I thought Bajaj Auto was a worthy cover story with Rahul Bajaj gracing the cover, the editor had other ideas.

Sure enough, before making the road trip to Akurdi, Pune, days after the call to the Bajaj corner room from our solitary office STD line, the good editor duly informed me that he had at least two options for the cover. Bajaj was not one of them.

The interview with Bajaj began with me breaking the unpleasant news that Bajaj Auto was not going to be the cover story. What followed in the next few minutes will not be printed. Suffice it to say that one of India’s most powerful and influential industrialists—a name on a par in those days with Ambani, Goenka and Birla—was not quite pleased as punch and reminded me, among other things, that he was a pugilist in his younger days. He did so by throwing a punch that stopped inches short of my nose. The best part of the jab is that it made for a great photograph that set up the opening pages of the story—not to show Bajaj’s distaste for an evidently deceitful hack, but how the combative patriarch was gearing up to take on the multinational Johnny-come-latelies in the liberalised two-wheeler industry.

Bajaj, of course, did the interview, out of grace or the inability to resist the opportunity to make a splash is something I was never able to figure out. Maybe it was a bit of both.

In today’s media world in which public relation agencies front negotiations with journalists for stories, requests for cover stories are a norm. But, in the 90s, in the wake of the first flush of economic liberalisation, business journalism was just beginning to come into its own. As was the PR industry. Head honchos oversaw their own image.

Bajaj was a past master in PR, and the media loved him for his flamboyance and outspokenness. As Gita Piramal wrote in Business Maharajas, first published in 1996, “Over the past ten years, the lanky (6"1") and handsome (but balding) Marwari has been on the cover sixteen times in magazines as varied as Asiaweek and the Poona Digest. The Indian business press adores him because he has built Bajaj Auto (sales 1995: Rs22 billion) into the world"s fourth largest two-wheeler manufacturer. Non-business journalists keep tuning in to Pune"s BBC (Bajaj Broadcasting Corporation) for his unflinching frankness and varied opinion on every topic under the sun."

Bajaj never shied away from a slugfest when he reckoned he was fighting the good fight. There was the long-drawn-out feud with the Firodias over control of shares they held in each other’s companies, which moved from the boardroom to the stock market to the courts. Then there was the feud with partner Piaggio of Italy, an alliance that began in the early 60s with Bajaj assembling the iconic Vespa in India. The tie-up ended roughly a decade later when the Indira Gandhi government refused permission to extend its term. The bad blood came to the fore when, a decade later, Piaggio accused Bajaj of pilfering Piaggio designs in a California district court. The former partners eventually settled out of court and, as Piramal wrote in Business Maharajas, “If Bajaj didn’t lose, neither did he win."

The war also revealed Bajaj’s clinical ability to separate business from the personal. "Journalists like to dramatise but quite frankly there was no hate," he is quoted in Piramal’s book. “It was a serious business fight. In their position I might have done the same bloody thing."

Much has been said and written about Bajaj’s criticism of the current government (perhaps because he was the only one to do so), but the grandson of Gandhian Jamnalal Bajaj had plenty of past brushes with political powers. The Indira Gandhi regime refused Bajaj Auto permission to expand manufacturing, prompting the patriarch to thunder: "My blood used to boil. The country needed two-wheelers. There was a ten-year delivery period for Bajaj scooters. And l was not allowed to expand. What kind of socialism is that?" Bajaj Auto’s fat profit margins would also invite the suspicion of subsequent Congress regimes, but the raids proved futile.

Bajaj did not always find himself on the winning side—the famous tussle for Ashok Leyland when the Rover Group put its stake in the commercial vehicle maker up for sale went down to the wire, with the Hindujas eventually winning (the third bidder in the fray was Manu Chhabria). Then, in the first half of the 90s, in response to what he thought was an unlevel playing field courtesy of economic reform, Bajaj attempted to band together what came to be infamously known as the Bombay Club to shield domestic businesses from the foreigner. Sections of media flayed the move as protectionist, and most of the big industrialists of the time steered away from it.

Fights are mostly fought to win, but a few are also fought because they need to be fought, even if one does not end up on the side that is winning. That was Bajaj for you, a maverick who thrived in breaking the mould. He did that in the early 60s, when he moved the headquarters of Bajaj Auto from Mumbai to Akurdi, then an obscure village on the outskirts of Pune. At a chance meeting almost a decade after the eventful maiden one—I was there to meet son Rajiv to understand his motorcycle strategy to take on Hero Honda—the patriarch, now in his mid-60s, was in a nostalgic frame of mind. “I insisted that my children study with the workers" children in a village school, rather than sending them to one of those fancy ones in Pune," Bajaj told me.

Frank Sinatra’s My Way is a journey many of us would like to emulate but you cannot be blamed if you think the song was written for Bajaj. He lived a life that was full, travelled each and every highway…and more, much more, he did it his way.

First Published: Feb 14, 2022, 09:27

Subscribe Now