Frank Wang Tao has never been arrested. He pays his taxes on time. And he rarely drinks. But on the eve of a January sit-down with Forbes—his first public interview this year with a Western publication—the Chinese national who happens to be the world’s first drone billionaire found himself on the wrong end of American authorities.

A US government intelligence employee in Washington, DC, some 8,000 miles away from Wang’s perch in Shenzhen, had had a little too much to drink and took a friend’s four-propeller drone out for a spin in the wee hours. Inexperienced, he lost the aircraft in the dark and, after a brief search, called off his drunken hunt. By dawn that 1-foot-by-1-foot whirlybird was a global news story and subject of a Secret Service investigation—after crash- landing on the White House lawn.

Wang built that robot. He also created the one that a protester used last month to land a bottle of radioactive waste on the roof of the Japanese prime minister’s office and developed the one a smuggler used to sneak drugs, a mobile phone and weapons into a prison courtyard outside of London in March. The idea of people using your product to break laws and social boundaries would give most CEOs nightmares, but the inconspicuous mastermind behind the world’s drone revolution just shakes it off.

“I don’t think it’s a big deal,” shrugs the 34-year-old founder of Dajiang Innovation Technology Co (DJI), which accounts for 70 percent of the consumer drone market, according to Frost & Sullivan. His company spent the morning developing a software update it blasted out to all its drones, prohibiting them from flying inside a 15.5-mile-radius centred on downtown Washington, DC. “It’s a benign thing.”

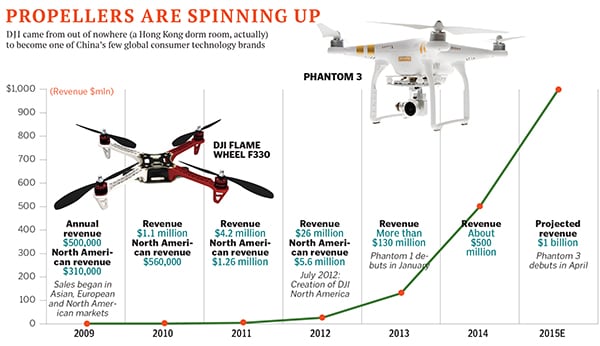

Or maybe it only looks that way to Wang because success has inured him to controversy. Last year DJI sold about 400,000 units—many of which were its signature Phantom model—and is on track to do more than $1 billion in sales this year, up from $500 million in 2014. Sources close to the company say DJI netted about $120 million in profit. Sales have either tripled or quadrupled every year between 2009 and 2014, and investors are betting that Wang can maintain that dominant position for years to come. In April the company raised $75 million from Accel Partners at a valuation of $10 billion. Wang, who owns about 45 percent, is now worth more than $4.5 billion. DJI’s chairman and two early employees are also paper billionaires from the deal. “DJI started the hobby unmanned aerial vehicle [UAV] market, and now everybody is trying to catch up,” says Frost & Sullivan analyst Michael Blades.

In the annals of technology it’s not often that one company can grab a dominant position in a market as it makes the leap from hobbyist to mainstream. Kodak caught that rogue wave with cameras. Dell and Compaq caught it with PCs, and GoPro with action cameras. Drone sceptics may have laughed at Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos’s vow to use UAVs to deliver packages, but drones are becoming a big deal. Widespread commercial use is already well under way: Drones broadcast live aerial footage at this year’s Golden Globes relief workers relied on them to map the destruction left behind by Nepal’s 7.8-magnitude earthquake in April farmers in Iowa are using them to monitor cornfields. Facebook will be using its own UAVs to provide wireless internet to rural Africa. DJI drones are being used on the sets of Game of Thrones and the newest Star Wars film. Now DJI needs to keep stoking the consumer market with better and cheaper flying machines, just as it did in January 2013 when its Phantom drone debuted, ready to fly out of the box at a price of $679. Before then you pretty much had to build your own drone for well north of $1,000 if you wanted a decent flier.

DJI faces the headwinds of cheaper rivals and rearguard bureaucrats at the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), which currently has a blanket ban on the commercial use of small drones without exemptions and has been slow to enact meaningful policy. A formidable challenge is brewing in 3D Robotics, a Berkeley, California company co-founded by former Wired magazine editor Chris Anderson and staffed by laid-off DJI employees. Among them is former DJI North America head Colin Guinn, who accused the Chinese company of screwing him over and called 3D Robotics the “David to DJI’s Goliath”. His new company, however, is fighting with more than slingshots—it has raised nearly $100 million. There’s also French manufacturer Parrot, which sold more than $90 million worth of drones in 2014, and a plethora of Chinese copycats eager to drive margins down for all. This year’s Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas saw dozens of barely hatched companies zipping their UAVs across Sin City’s cavernous conference halls.

With his circular glasses, tuft of chin stubble and golf cap that masks a receding hairline, Wang cuts an unlikely front man for a new consumer tech powerhouse. Still, he takes his role as seriously as when he launched DJI out of his Hong Kong dorm room in 2006. Wang is on a warpath—discarding former business partners, employees and friends—as he seeks to turn DJI into a top-ranked Chinese brand akin to smartphone maker Xiaomi and ecommerce powerhouse Alibaba. Unlike those two, however, DJI may become the first Chinese company to lead its industry. Its dominance has earned it comparisons with Apple—not that Wang has much use for the implicit praise.

Dashing into his office, he passes a Chinese-language sign on his door that reads ‘Those with brains only’ and ‘Do not bring in emotions’. The DJI CEO abides by those rules and is a sharp-tongued, head-over-heart leader who works more than 80 hours a week and keeps a twin-size wooden bed near his desk. Wang says he was a no-show at DJI’s April launch of its new Phantom 3 in New York because “the product was not as perfect” as he expected.

“I appreciate Steve Jobs’ ideas, but there is no one I truly admire,” he says in his native Mandarin. “All you need to do is to be smarter than others—there needs to be a distance from the masses. If you can create that distance, you will be successful.”

Frank Wang’s infatuation with the sky began in elementary school after he started devouring a comic book about the adventures of a red helicopter. Born in 1980, Wang grew up in Hangzhou, Alibaba’s home city on China’s central coast. The son of a teacher turned small-business owner and an engineer father, Wang spent most of his time reading about model airplanes, a pastime that offered more comfort than his middling grades. He dreamed of having his own “fairy”, a device that could fly and follow him with a camera. When he was 16 Wang received high marks on an exam and was rewarded with a long-coveted remote-controlled helicopter. He promptly crashed the complicated device and waited for months for replacement parts to arrive from Hong Kong.

Wang’s less-than-stellar academic performance thwarted his dream of landing at an elite American university. Rejected by his top choices, MIT and Stanford, he ended up at the Hong Kong University of Science & Technology, where he studied electronic engineering. He didn’t find his sense of purpose until his senior year, when he built a helicopter flight-control system. Wang devoted everything to his final group project, skipping classes and staying up until 5 am. While the hovering function for the onboard computer he built failed the night before the class presentation, his effort did not go to waste. Robotics professor Li Zexiang noticed Wang’s group leadership and technical understanding and brought the headstrong student into the school’s graduate programme. “I couldn’t tell that [Frank] was smarter than others,” says Li, who served as an early advisor and investor to DJI and now owns about 10 percent as its chairman. But “good performance [at work] was not necessarily comparable with good grades.”

Wang built prototypes of flight controllers out of his dorm room until 2006, when he and two classmates moved to the manufacturing hub of Shenzhen. They worked out of a three-bedroom apartment with Wang funding the venture using what was left of his university scholarship. DJI sold his $6,000 component to clients such as Chinese universities and state-owned power companies, which soldered them onto the frames of DIY drones. Those sales allowed Wang to pay for a small staff, while he and the other former HKUST students lived off what was left of their university scholarships. “I didn’t know how big the market could be,” Wang remembers. “Our idea was to just make the product, feed 10 to 20 people and have a team.”

The lack of an early vision and Wang’s personality would eventually cause strife within DJI’s ranks. There was constant churn among employees, with some feeling spurned by a demanding boss they felt was stingy with equity. By the end of two years almost all of the founding team had departed. Wang admits he can be an “abrasive perfectionist” and at the time managed to “piss [employees] off.”

Yet DJI chugged along, selling about 20 controllers a month. It survived off capital from Wang’s family friend Lu Di. In late 2006 Lu had put in about $90,000—the only money DJI has ever needed says Wang. Endearingly called a “penny-pincher” by DJI’s CEO, Lu managed the finances and today remains one of the largest shareholders, with 16 percent worth $1.6 billion, based on Forbes estimates. Also key to DJI’s development was Wang’s best friend from high school, Swift Xie Jia, who, in 2010, came in to run marketing and act as confidante. The man nicknamed “fat-headed fish” by Wang sold his apartment to invest in DJI and today holds a 14 percent stake worth an estimated $1.4 billion.

With his inner circle in place, Wang continued to build on product offerings and began selling to hobbyists abroad, who were emailing him from places such as Germany and New Zealand. In the US Wired editor Chris Anderson had started DIY Drones, a UAV-enthusiast message board, where users advocated for the move from single-rotor designs toward four-propeller quadcopters, which were cheaper and easier to program. DJI started making more advanced flight controllers with autopilot functions, which Wang then marketed at niche trade shows like a radio-controlled helicopter gathering in the 70,000-population town of Muncie, Indiana, in 2011.

It was in Muncie that Wang first met Colin Guinn, a well-built Texan, whose angular good looks once graced reality TV show The Amazing Race. Guinn, who ran an aerial cinematography startup, was looking for a way to shoot stabilised video from a UAV and had reached out to Wang by email to see if the young Chinese company had a solution. Wang was working on exactly what Guinn needed, a new kind of gimbal that used onboard accelerometers to adjust its orientation on the fly so the video frame remained still despite a drone’s shaky flying. Wang had gone through at least three gimbal prototypes—and one incapable intern—before he had a decent one. Wang figured out how to connect the drone’s motor to the gimbal so it wouldn’t need its own motor, cutting down on parts and weight. By 2011 the cost to make a flight controller had dropped to less than $400 from $2,000 in 2006.

After initially meeting DJI executives in Muncie in August 2011, Guinn flew out to Shenzhen and eventually formed DJI North America, an Austin, Texas, subsidiary aimed at delivering drones to the mass market, with Wang’s blessing. Guinn was given 48 percent ownership of the entity, with DJI retaining the remaining 52 percent. Guinn was put in charge of North American sales and much of its English-language marketing, quickly developing a new motto for the company: ‘The Future of Possible’. The relationship initially went well. Wang remembers Guinn as a “great salesman” whose “ideas sometimes inspired me”. By late 2012 DJI had put all the pieces together for a complete drone package: Software, propellers, frame, gimbal and remote control. The company unveiled the Phantom in January 2013, the first ready-to-fly, preassembled quadcopter that could be up in the air within an hour of its unboxing and wouldn’t break apart with its first crash. Its simplicity and ease-of-use unlocked the market beyond obsessed enthusiasts.

Yet things had already started falling apart between Wang and Guinn. DJI’s founder didn’t like that Guinn was taking credit for the development of the Phantom and was calling himself CEO of DJI Innovations, a title that still stands on his LinkedIn page. Sources also say that Guinn would often rush into setting up partnership agreements, particularly one with action-camera maker GoPro, which would have been an exclusive camera provider for DJI’s drones. Wang got cold feet in that deal and went against Guinn’s advice, subsequently angering GoPro, which is now rumoured to be developing its own drone.

Initially DJI was planning to only break even on the Phantom’s $679 retail price. “We made an entry-level product to prevent competitors from entering a price war,” says Wang. The Phantom, however, quickly became the company’s bestselling product, increasing revenue five-fold with little marketing. More important, it sold around the world, a trend that holds today as the company derives about 30 percent of revenue from the US, 30 percent from Europe and 30 percent from Asia, with the remainder from Latin America and Africa. That’s a source of pride for Wang. “Chinese people think imported products are good and made-in-China products are inferior. We’re always second class,” he says. “I’m unsatisfied with the overall environment, and I want to do something to change it.”

By May 2013 DJI attempted to buy out Guinn’s stake in DJI North America, offering DJI Global shares that would have given the American a paltry 0.3 percent stake, according to court documents. Guinn demurred, pointing out that it was his office’s work that led to 30 percent of Phantoms being sold in the US. DJI did not leave room for negotiation and by December had locked all of DJI North America’s employees out of their emails and redirected all customer payments to China headquarters. By New Year’s Eve the employees had been fired and arrangements were being made to liquidate the Austin office’s equipment. DJI ended that year with $130 million in revenue.

Guinn subsequently sued in early 2014, though the parties eventually settled out of court in August for an undisclosed amount under $10 million, according to sources. That’s slightly more than what the share-exchange deal would have been worth at the time, given that Sequoia Capital invested a little more than $30 million in mid-2014 at around a $1.6 billion valuation. “To say I had nothing to do with the Phantom would be hilarious, just as it would be to say I was the inventor of the Phantom would be hilarious,” says Guinn, who with many of his former colleagues joined 3D Robotics to take on their past employer.

![mg_81723_drone_280x210.jpg mg_81723_drone_280x210.jpg]()

The greatest threat to Wang’s dominance of the consumer drone market emanates from a sun-drenched fourth-storey office patio across the bay from Silicon Valley in Berkeley, where the engineers for 3D Robotics spent dozens of hours testing the latest code tweaks in their Phantom-killer, the Solo. Unveiled in April, the black drone whirs and buzzes around the roof with the sound of a thousand angry bees as 3D Robotics CEO Chris Anderson explains how his company is the Android to DJI’s Apple.

In admiring his quadcopter’s elegance and simplicity—which took cues from the Phantom—the affable Anderson explains that it is the software, not hardware, that is the key. Unlike DJI’s operating system, which is closed to developers, 3D Robotics made its OS open source to attract the interest of programmers and other companies such as the dozens of Chinese copycats undercutting DJI’s margins with even cheaper drones. If everyone is using our software, says 3D Robotics’ CEO, then we, not DJI, will control the market. “DJI started as a company back in the days when it was just a hobby for me, and to their credit they accelerated brilliantly,” he says. “Right now we’re playing on their home field, so we’re playing catch-up.”

3D Robotics, which has funding from the likes of Qualcomm and SanDisk, is well into its game of catch-up and has moved most of its manufacturing capacity from Tijuana, Mexico to Shenzhen. Guinn, who is the company’s chief revenue officer, is also exploring the same retail channels he built up with DJI and developed a partnership to put GoPros on 3D Robotics’ drones.

Wang dismisses their chances, sounding something like the big kid on the kindergarten playground. “It’s easier for them to fail,” he says. “They have money, but I have even more money and am bigger and have more people. When the market was small, they were small and I was small, too, and I beat them.” For all the drama between 3D Robotics and DJI, they face a common challenge in shaping public opinion and softening regulators. For every breathtaking video of a humpback whale migration or collapsing glacier taken from a drone, there’s a headline of a UAV being used by Isis or spying on a neighbour’s hot tub. Legitimate privacy and safety concerns have limited society from welcoming flying robots with open arms, and regulators, particularly the United States’ FAA, have been slow to enact meaningful regulations as a result. “There are no drones in the sky right now, and that is so weird,” says Anderson. “When you talk about a blue sky opportunity, we really are looking at one.”

Back in his office in Shenzhen, Wang is foretelling the future of the consumer drone industry, but his explanation is hard to follow as he wields a 450-year-old Japanese samurai sword on a hapless business card. “Japanese craftsmen are constantly striving for perfection,” he says, as the katana carves up the paper into pieces. “China has money, but its products are terrible, its service is terrible, and you have to pay a hefty price for anything that’s good.”

DJI is a long way from reaching the level of perfection in Wang’s Japanese artifact. The CEO openly acknowledges that his Phantom is “not a perfect product” and that some models have been known to fly away from users because of software malfunctions. “We do have room for improvement,” concedes Wang, who says that he’s adding to DJI’s 200-plus support staff.

Wang is also dealing with various levels of corporate espionage. He’s sure that a few of the Chinese drone startups to pop up in the past two years have done so with illegally obtained DJI designs. Wang has had to deal with at least two instances of internal spies, including one where a departing employee took blueprints and sold them to a competitor. That certainly doesn’t help in what Wang calls the “dog-eat-dog society” of Shenzhen, where cheap manufacturing will certainly see drones go the commoditised way of smartphones and laptops. Prices will certainly drop and the “boutiqueness of the market always gets driven out,” says Gartner analyst Gerald Van Hoy. “But DJI will do okay because they’ve established themselves in the market and they have recognition.”

Wang doesn’t want to share the skies with others, intent on maintaining DJI’s lead as drones expand into commercial applications like agriculture, construction and mapping. “Our main bottleneck for growth right now is the speed at which we come to realise answers to technical puzzles,” he says. “You can’t be satisfied with the present.”