Checkmate: Why don't we have more women grandmasters?

Divya Deshmukh recently became the fourth woman grandmaster in a country that has 89. What stops women from breaking through?

In 2002, when Koneru Humpy earned the title of a grandmaster (GM), the then-15-year-old was believed to have unlocked the Judit Polgar moment in Indian chess. Polgar, the Hungarian prodigy, had shattered the proverbial glass ceiling by breaking into the world’s top 10 in the open section, a feat that no woman has matched yet. Many had hoped that Humpy’s feat—of becoming India’s maiden woman GM after six male predecessors—would spark a wave of women storming the game’s elite ranks.

But a little over two decades on, the gender gap in chess remains yawning: Out of India’s 89 GMs, the highest rank a chess player can achieve, only four are women.

The latest among them is 19-year-old Divya Deshmukh, who just weeks ago became the youngest winner of the Women’s World Cup, defeating none other than Humpy, who started it all. Her GM title places the Nagpur teen not just among a rarefied cohort in India, but globally as well: She is only one of the 44 women to have earned the GM title awarded by FIDE, which means just about 2 percent of the world’s 1,866 GMs are women.

The gulf is visible even among those who’ve made it. Yifan Hou, the world’s top-ranked woman chess player, doesn’t even crack the top 100 in the open list, and has an over-200 ratings points deficit with Magnus Carlsen, the five-time world champion and World No. 1 while, Deshmukh, despite being the world No. 1 among girls, sits at No. 70 in the junior open section.

“World over, there is a struggle to produce strong women players. I have worked with a lot of good players, like Divya, R Vaishali [India’s third woman GM], when they were very young. I’ve noticed that the difference between boys and girls starts widening from the age of 9 or 10. So if they have the same rating at the age of 7, in a few years, the difference in their ratings widens to 200-300 points," says Ramesh RB, a GM and a trainer, who has coached Vaishali and R Praggnanandhaa, the first brother-sister grandmaster duo.

In 2002, Koneru Humpy became India"s first woman GM after six male predecessors. Humpy remains one of India"s leading chess players, winning the world rapid title in 2024 and finishing as the runner-up in the Women"s World Cup last month Image: PTI Photo via FIDE/Michal Walusza

In 2002, Koneru Humpy became India"s first woman GM after six male predecessors. Humpy remains one of India"s leading chess players, winning the world rapid title in 2024 and finishing as the runner-up in the Women"s World Cup last month Image: PTI Photo via FIDE/Michal Walusza

The Mind Game

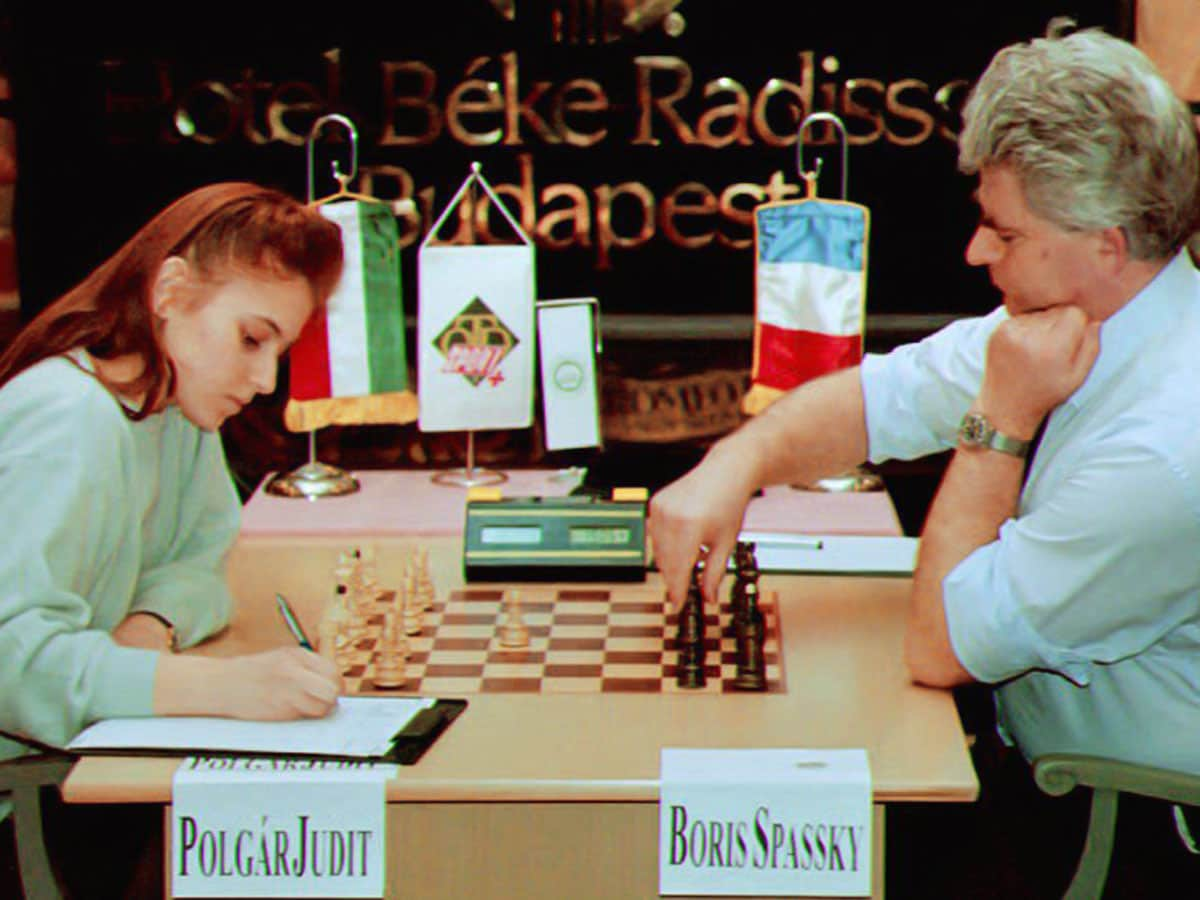

The argument has surfaced before, famously (or infamously) in 2015, when British GM Nigel Short, currently Fide’s director for chess development, sparked a furore by claiming that men were hardwired to be better at chess than women and that “we should gracefully accept it as a fact". Short’s comments had triggered severe backlash, including from Polgar, who has defeated not only Short, but also the likes of legends Garry Kasparov and Boris Spassky.

“Short was disparaging, and I speak from observation," says Ramesh. “I’ve attended seminars in the US and Europe where this widening gap is being discussed as well."

That men and women play chess differently is a sentiment that finds resonance among other veterans of the sport within India as well. Pravin Thipsay, the country’s third GM who has spent years training young players, feels men have a slight edge in the courage of decision-making on the chess board. “From the experience of training a number of kids, I feel women expect a higher degree of certainty in life, while chess involves unpredictability with every move. Polgar is an exception, but I will consider her a one-off," says Thipsay, a GM since 1997. “I have seen that after three to six months training, a boy always plays better chess than a girl even when they are of the same age and social background."

Both Thipsay and Ramesh say they can’t pinpoint the science behind the pattern, but they feel it could be because an error dents a girl’s confidence more. Ramesh recalls one of his students berating her calculation skills after losing to a higher-ranked player. “I was shocked, because I thought calculations were her strong point," he says. “But she dwelled on it, and lost the next match too in a similar manner. Her fears became a reality." For him, the difference is psychological: Girls tend to take losses more personally and have trouble moving on. “Boys don’t fear being judged if they’re wrong," he says.

How psychology leaves an imprint on the chess board is evident from the pressures that Swati Ghate, a Women’s Grandmaster (WGM, a title exclusively for women), faced during the 1998 Elista Chess Olympiad. Having scored 4.5 points in her first five games that put her in medal contention, Ghate faltered and lost the next four games in a row. “It was a pattern. I would have great starts and then crumble under pressure," says Ghate.

But mind over matter may not be the entire story. Sports psychologist Gayatri Vartak Madkekar, a former badminton international herself, agrees that while men have a better spatial awareness that might give them an edge in chess, women are naturally wired to process information more emotionally than logically. “But both these qualities can be developed over time," says Vartak Madkekar, the founder of Samiksha Sports. Her observations tie in well with what Hungarian educational psychologist Laszlo Polgar had proclaimed—that geniuses are made, and not born—while nurturing his three daughters, Susan, Sofia and Judit, to the heights of chess success. While Judit, the youngest, was the most successful, Susan, too, turned out to be a GM, while Sofia was an International Master (IM, a rank below GM).

“In my work with athletes," adds Vartak Madkekar, “I have seen it’s not just women who take losses personally, men do too." In a recent such example, the all-conquering Carlsen was seen banging the table in frustration after losing a match to world champion D Gukesh in the Norway Chess tournament 2025. “Just that, with women, getting over losses translates into its impact on confidence and slowly on self-esteem, like, I am not good enough," says Vartak Madkekar. “Some of these doubts are shaped by culture and environment… that’s how attitude within the sport has taught women to think over the years."

The Second Sex?

The inherent sexism Madkekar talks about hasn’t spared even some of the sport’s most elite. Polgar, among the most trailblazing chess players, was called a ‘circus puppet’ by Kasparov before her victory over him forced an about-turn and a public apology. In India, the Khadilkar sisters—Vasanti, Jayashree and Rohini—who swept the national championships for 10 consecutive years, beginning 1974, faced staunch resistance from the men, especially when they played in the open category and started winning. In an interview with Espn.in, Rohini, a five-time national champion, mentions: “Sometimes opponents would light cigarettes and blow smoke my way. I would be coughing and my eyes would sting."

While the overt hostility has faded, structural and systemic biases remain. Polgar says: “From the very beginning, if a coach sees a talented boy, he is told that he can become the best player like Carlsen, while a talented girl is told she can become a women’s champion. In reality, there are a few hundred rating points difference between the two achievements. If you set the bar low, it limits the girls’ potential at a young age."

A file photo of Judit Polgar playing Russian legend Boris Spassky in 1993. Polgar, who is the only woman to have broken into the top 10 of the open category, went on to win the game Image: Attila Kisbendek / AFP

A file photo of Judit Polgar playing Russian legend Boris Spassky in 1993. Polgar, who is the only woman to have broken into the top 10 of the open category, went on to win the game Image: Attila Kisbendek / AFP

Nisha Mohota, an IM and a multiple national champion, recalls hearing from a young trainee that he was told by his coach, in the presence of girls, that the latter weren’t good at chess. "When this happens over and over again, women are conditioned to think they are not as good as men," she says.

That stereotyping affects performance was proven through a 2008 study done by researchers at Italy’s University of Padua that matched 42 expert women chess players with similarly ranked male opponents online. It was seen that the women performed according to their potential when the gender of their opponents wasn’t revealed, but their performances slipped dramatically when they knew they were fighting men on the board.

“Among a man and a woman rated 2,500, I respect the latter more because she has had to sacrifice more, because, first, a woman has to fight her natural conciliatory instinct and switch to being aggressive on the board, and second, she has to fight the outside world," says Mohota. “Humpy and Harika have to leave behind a child to play chess. However much you argue, it’s not the same as a father leaving behind a kid."

In 2023, R Vaishali broke a 12-year wait to become the country’s third woman GM Image: CAPTION]

In 2023, R Vaishali broke a 12-year wait to become the country’s third woman GM Image: CAPTION]

That apart, a woman stands at a disadvantage even when you consider social attitudes. Take for example, chess requires a player to practise with a coach in privacy, and then travel to tournaments in the company of male coaches. “As the parent of a girl, there is always an apprehension of safety, which isn’t the case with boys," she says further. It’s not just the case in India, but abroad as well. At the Commonwealth championships, Thipsay recalls seeing the South African girls being accompanied by each of their mothers, while only one parent would accompany the team of boys.

Add to that the incentives. While Norway Chess became the first top-tier international tournament to offer equal prize money to both the men’s and women’s winners last year, and Indian national championships have also caught up on the prize purse, the discrepancy is stark when it comes to the world championships. Deshmukh pocketed a paycheque of $50,000 for winning the World Cup, while Gukesh, the men’s world champion, took home a total of $1.35 million.

Mohota recalls that she received zero support for training and foreign exposure when she reached a rating of 2,416, within sniffing distance of the GM threshold of 2,500, and was within the top 50 in the world among women, in 2007. “Chess is a very expensive sport. One of the national champions I know is still unemployed," she says. And while the pay parity gap has reduced over the years, all other inequalities remain where they are. “You can argue society has changed from that time, but has that change been enough? Are men and women really considered equal?" she asks.

[caption](File) Players take part in matches during the World Junior Chess Championship in Pune. Image: STRDEL / AFP

[caption](File) Players take part in matches during the World Junior Chess Championship in Pune. Image: STRDEL / AFP

Level-Playing Field

It’s no surprise, then, that the pool of women chess players is far smaller than men. According to FIDE, in 2023, around 10 percent of the rated players were women, crawling up from 8 percent in 2012. The gap is stark in the junior nationals too: The number of participants in the open categories of the under-9 and under-11 national championships this year stood at 317 and 452, respectively, while the numbers in the girls category were at 171 and 200.

“Right from a very early age, 70-80 percent of entrants in open competitions are boys. When you enter the field itself, there is an overwhelming difference in numbers that perhaps creates gender stereotypes," says Ramesh. At chess clubs run in Mumbai by Sagar Shah, IM and the founder of Chessbase India, among the most exhaustive resources on the sport in the country, women make up just about 25 percent on a good day.

Exposure, players argue, make a world of difference. Greater exposure from a young age makes men’s chess versatile—their openings are diverse, attacks unpredictable. While women, playing within a limited pool, develop a limited repertoire. “At a ratings level of around 2,200, a winning position against women holds. While against men, it’s not so certain," says WGM Swati Ghate. “With wider exposure, men have brought in a lot of ingenuity, while when I would prepare against women, I knew the predictable lines along which their games would go."

That raises the question: Should women-centric chess titles—WGM, WIMs etc—be eliminated and women’s-only tournaments scrapped? “Women’s chess as a division is obsolete in the modern era, though it must have started with good intention. The time has come to burst the bubble and think of new ideas," says Amruta Mokal, a former national champion and the co-founder of Chessbase India. “We need chess as a mixed gender game where women can fight with the best to gain confidence because that plays a key role in decision-making with every move. And it can’t happen without the support of good men. Judit has shown how mental strength can bring in a breakthrough."

But it shouldn’t be an overnight process and should allow women to transition, through a few decades, to a position of equal strength. As things stand now, most women GMs are unlikely to qualify for the open categories of the elite invitation tournaments based on ratings and performances. At the prestigious Tata Steel Chess Masters earlier this year, both Vaishali and Deshmukh ended up 9th and 12th respectively among 14 players in the challengers category. In the recently-concluded challengers category of the Chennai Grandmasters event, Harika Dronavalli and R Vaishali finished in the last two spots, up against eight male Indian players GM Nihal Sarin, who has an over-200 point ratings points lead over Deshmukh, the World Cup winner, hasn’t yet been able to make it to the Candidates, the qualification rounds for the open world championship. “If you abolish the women’s-only tournaments now, there will be no incentive for women to play and progress to the next level," says Thipsay.

New Wave Rising

When Kasparov took potshots at her, says Polgar, it came from the milieu he grew up in, where no woman excelled in the highest levels of chess. “The girls have to change that viewpoint, but they need the right environment and support system," says the Hungarian legend, who spurned women’s tournaments and played in the open category.

But she doesn’t think the time is ripe to eliminate women’s tournaments—it’s complicated and can’t be done with one fell swoop, she adds instead, why not try an experiment of abolishing women’s-only titles and introducing more titles on the pathway to GM. “Add some universal titles for lower Elo ratings for all. What I have experienced is that it’s not girls that want to take it easy, but it’s again societal pressure—with time and money being invested in turning kids into chess players, a title against their name adds validation for parents and coaches," she says. “So if we increase the number of universal titles en route to GM, girls can reach milestones while being on par with boys."

Of late, Indian women’s chess has been on a remarkable run. The women’s team clinched gold at the 2024 Budapest Olympiad, with Deshmukh and Vantika Agrawal adding individual gold medals to the tally. In 2023, R Vaishali broke a 12-year wait to become the country’s third woman GM, and then went on to play the Candidates along with Humpy, where they finished joint second. Late last year, Humpy became the world champion in the rapid format. Now with Deshmukh’s World Cup triumph and Humpy’s runner-up finish, there’s much to celebrate, and hope for a resurgence.

“In the 2022 Chess Olympiad in Chennai, Gukesh at 16 years and 2 months won the gold medal in board 1, Nodirbek Abdusattorov who is two years older to him won silver," says Thipsay, the head of the Indian delegation. “In the women’s section, it was veteran Pia Cramling of Sweden who won the gold in board 1. The Indian team had five players all of whom except Vaishali were above 30. Now, that is going to change with the likes of Deshmukh and Agrawal coming in."

With 89 GMs, it’s India rising in world chess. But for the country to truly become a superpower, the next frontier isn’t just more GMs—it’s making sure they aren’t all men.

First Published: Aug 22, 2025, 10:53

Subscribe Now- Home /

- Upfront /

- Take-one-big-story-of-the-day /

- Checkmate-why-dont-we-have-more-women-grandmasters