How ChrysCapital holds its own among the biggest global PE firms

It raised its 10th and largest fund of $2.2 billion—the largest India-focussed fund anyone has raised—in November. Now, it needs to break fresh ground

In 2007, the year ChrysCapital first wrote a cheque to Mankind Pharma, the drugmaker was in the public eye for its Manforce brand of condoms. It had become a full-fledged pharma company by the time the private equity (PE) firm exited in 2015.

Along the way, Mankind, nudged by ChrysCapital, got into chronic therapies and stepped out of its small-town comfort zone. Today, nearly a third of Mankind’s business comes from chronic therapies and metros bring in two-thirds of its revenues. The company also acquired Bollywood icon Amitabh Bachchan as its corporate brand ambassador, while actor Sunny Leone came on board as the face of its condom brand.

“Truly transformative,” says Mankind’s global CFO, Ashutosh Dhawan, describing the repositioning, “especially in shaping product strategy and sharpening our thinking on how to build big, profitable brands”.

Mankind was not the only party in this relationship to reap the benefits. ChrysCapital’s initial ₹100 crore investment yielded 11 times more in returns when it exited Mankind in 2015, selling its stake to Capital International.

“That growth did not happen by accident,” adds Dhawan. “ChrysCapital had strong domain knowledge in pharma, so it was able to guide and mentor us effectively.”

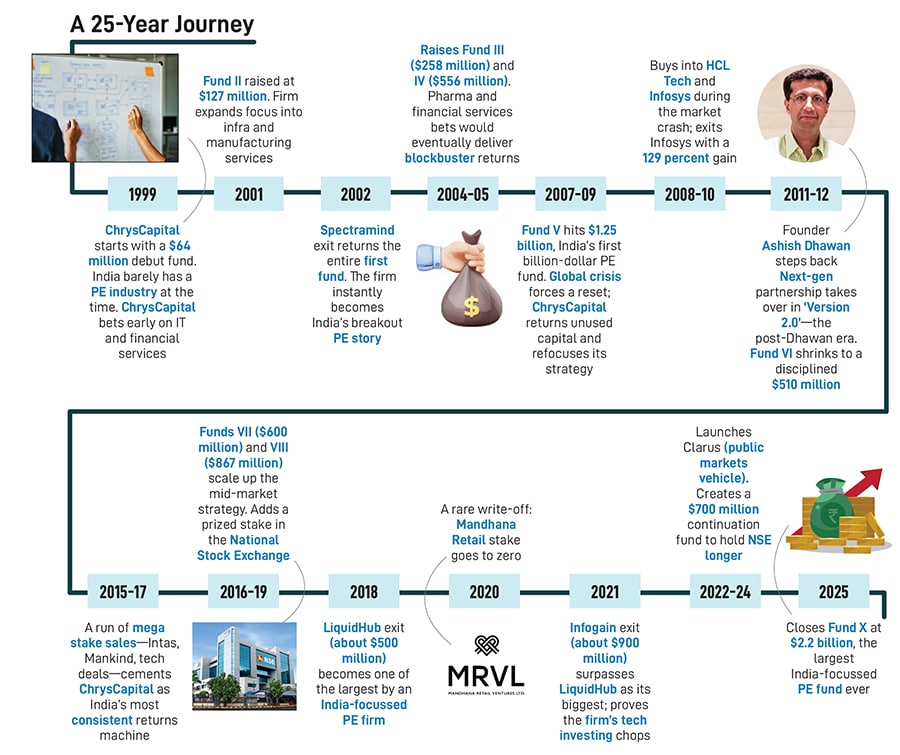

The PE firm returned to Mankind in 2018, picking up a 10 percent stake, trimmed its position in the company’s public float in 2023, and exited entirely by 2024. But it is ChrysCapital’s first stint with Mankind that presents a peek into the playbook the homegrown firm has followed—and helped write—as India’s PE sector took its first baby steps at the turn of the century, buoyed by the dotcom boom, rattled along through the global financial crisis of 2008, rode the waves of telecom and technology, and has now reached a place where deal sizes are larger, buyouts are burgeoning, and interest in India-focussed funds is at an all-time high.

A report by Equirus Capital says PE and venture capital (VC) investments in the country touched a three-year high of $26 billion in the first nine months of this calendar year, surpassing the combined figure for 2023 and 2024. This despite the high valuations commanded by the public markets, which tend to channel funds from PE to listed stocks.

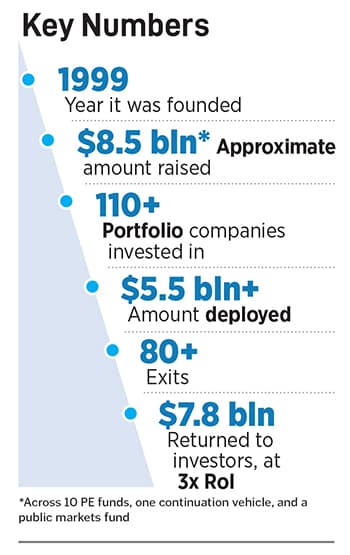

ChrysCapital, for its part, raised its 10th and largest fund of $2.2 billion—the largest India-focussed fund anyone has raised—in November. What’s more, this fund has become its first to attract money from Indian investors, in addition to the usual sovereign and endowment funds from abroad, enhancing the Indianness of its appeal, which it has leveraged during its rise to becoming the largest homegrown PE firm. With $8.5 billion raised across its 10 PE funds, a continuation vehicle, and a public markets fund, ChrysCapital holds its own among the biggest global names in the fray, such as Blackstone, KKR, Warburg Pincus, Carlyle and Temasek.

The year was 1999, the dotcom boom was in full swing, and New York’s financial district hummed with the promise of easy money. Ashish Dhawan was 29 and on a lucrative ascent at Goldman Sachs, the Wall Street giant. He chose to walk away and boarded a plane to India with the audacious idea of importing Silicon Valley’s VC playbook into a market still seen as untested terrain.

Together with his Harvard batchmate Raj Kondur, Dhawan co-founded ChrysCapital (then called Chrysalis Capital). After the dotcom bubble burst, it did not take the duo long to realise the VC model did not work for them. They quickly transitioned to PE and began a journey of growth that has continued despite Dhawan’s exit from the company in 2012. Kondur had left in 2002 to start a business process outsourcing firm called Nirvana Business Solutions.

Through its PE funds, the firm has deployed $5.5 billion in more than 110 companies. It has already returned $7.8 billion—a three-fold return on investment—to its investors through 80-odd exits.

But the last 25 years were not a breeze. When ChrysCapital started, it was an unknown name in an industry that itself was unknown in India.

“Twenty years ago, you had to really fight with the entrepreneur to get them to dilute stake. It was mostly, ‘Oh I only want to give 5 percent’, and us on the other hand going, ‘No, we want 10 percent’,” says Kunal Shroff, the firm’s managing partner.

For one, the ChrysCapital brass believes, the firm’s track record of transforming companies and enhancing value began to resonate with entrepreneurs. Second, succession happened at family businesses. The new generation does not automatically want to take over the business and run it, especially where the group’s best days may be behind it. Third, ChrysCapital got better at it.

“When we started, there were a lot of things we were learning on the go,” says Sanjay Kukreja, partner and CIO.

More entrepreneurs are now willing to give up larger stakes. Almost half of the deals in ChrysCapital’s ninth fund have resulted either in giving it control or joint control. Along the way, ChrysCapital developed sector-specific expertise.

Also Read: India’s private equity machine powers up

Working with PE is a challenging, exciting and stimulating experience, says an executive who has worked with PE firms.

When a PE firm invests in a company, it usually focuses on three areas: One is profitable growth. Second is governance, which enhances valuation, raising the value of the PE firm’s holding above the price it paid. The third thing, says the executive, is a sense of accountability for the promoter, which is important because in family businesses, it is sometimes difficult for the professionals to question the promoter. “But PE brings in best practices, mainly by benchmarking your actions against what rivals are doing,” says the executive.

When ChrysCapital works with a company, a big focus area is inorganic growth. “We have done more than 50 M&A (mergers and acquisitions) transactions in our portfolio companies with a very high degree of success,” says Kukreja.

In 2016, ChrysCapital wanted Intas, the pharma company, to acquire Actavis to strengthen its play in the retail markets of the UK and Ireland. “They told us: Aap log dekh lo (you guys evaluate it and decide),” says Shroff, highlighting the trust entrepreneurs place in the PE firm.

ChrysCapital also got Intas to invest in newer areas like biopharma. These interventions change companies. When ChrysCapital entered Hero Fincorp, it was a strong NBFC (non-banking financial company). The firm suggested a move into housing finance; today, that business is the same size as Hero Fincorp’s entire operation at the time of ChrysCapital’s investment.

“Our goal is to ensure the company we exit five years later is a very different one from the company we enter,” says Kukreja.

Awfis provides a more recent example. Amit Ramani, chairman and MD at Awfis Space Solutions, says: “Chrys came in around 2019, at a time when we were moving from a classic startup phase to a more scaled, growth-stage company. That transition is tricky for any founder—you are still building, but the expectations on structure, governance and predictability go up sharply.”

ChrysCapital’s biggest contribution, he says, was helping Awfis think from first principles, which is a set of the most fundamental and important reasons for doing or believing something. Corporate strategists use this technique to break down complicated problems and generate original solutions.

“They pushed us to be very clear on unit economics, returns on every rupee deployed, and what levers really matter for sustainable growth. That led to sharper choices—diversifying the business thoughtfully, building multiple lines like managed offices and design and build, and being more disciplined in how and where we expanded,” says Ramani.

ChrysCapital encouraged the flexible workspace operator to upgrade leadership, tighten governance and put in place incentives for the team to align with long-term value creation, not just short-term targets. In many ways, says Ramani, ChrysCapital helped Awfis shift from a “fast-growing startup” to an “enduring platform”. That was critical in getting Awfis ready for the public markets.

Also Read: ChrysCapital closes new fund with record $2.2 billion raise

ChrysCapital began as a generalist VC investor, but by 2015 realised specialisation was essential, says Rishi Sahai, managing director at Cogence Advisors, a mid-market investment bank. “Their biggest successes—Mankind, Eris Lifesciences, Intas and other pharma-health care bets—came after they developed deep domain expertise in those areas, which have now become their defining edge,” he says.

Success also comes from knowing what to avoid. The focus remains on three things: Return on capital employed, alignment with the entrepreneur and sector expertise, and avoiding anything that does not meet these criteria.

ChrysCapital has a portfolio value creation team called Enhancin, which is a bunch of people who sit with companies where the firm has invested once or twice a week to help them work through issues. Sanjiv Kaul, a partner at the firm, says ChrysCapital realised seven to eight years ago that merely working with the entrepreneur at the board level was not going to bring in the changes required to drive profitability, which was critical to bump up valuation and allow ChrysCapital a successful exit. That led to the birth of Enhancin.

This team does cost optimisation, supply chain management, board governance, M&A activities and even helps recruit CXOs—not only at the companies ChrysCapital controls but also where it is an investor without having control.

“In every sector we have almost about 200 folks whom we know and who we can bring to the table,” says Kaul.

Fifteen companies in ChrysCapital’s portfolio have floated initial public offers and more are in the pipeline.

During this prolonged exuberance in the stock markets, when limited partners (LPs)—people and entities who park their money with PEs, VCs and other funds—can invest directly and profitably in listed stocks, what is ChrysCapital’s appeal?

Shroff’s answer—met with chuckles all around the table—was disarmingly simple: “It is Gaurav Ahuja.”

Ahuja, one of the partners at the firm, is all seriousness. “Our flagship is the PE practice, but we also have a public market fund for people who are looking for more liquid strategies.” They can choose either based on their risk appetite.

The public markets fund—Clarus—was launched in March 2023 and has consistently outperformed the benchmark indices. “We have delivered four to five percentage points of alpha, which is actually quite good, given how good the market has been over the past two-and-a-half-years,” says Shroff.

Ahuja says investors come to ChrysCapital for three things: Longevity of the fund, stability of the team and consistency. “And we have delivered that even though we went through a founder transition.”

That founder transition—Dhawan’s departure 13 years ago—could have rattled the firm. Instead, it became an unlikely proof of strength.

“The firm has built institutional rigour and operated with open communication and transparent disclosures on a par with many global firms from the very beginning,” says Sunil Mishra, partner, Primary Investments Asia, Adams Street Partners, a Chicago-headquartered private markets investment manager which invests as an LP with ChrysCap. Adams Street has $65 billion in assets and has invested more than $1 billion in India over the last 20 years across a dozen PE and VC firms.

It was one of the first global fund of funds to invest in ChrysCap, in 2004. “This was Adams Street’s first investment in Asia and in India. We actually got to know the team when they were raising their first fund in 1999,” adds Mishra.

For global PEs, the minimum ticket size for investing in India is $500 million and above. Smaller domestic PEs, which have raised $300-500 million funds, can do deals worth $25-50 million. ChrysCapital sits somewhere in the middle, with an average ticket size of $150 million.

But there are challenges.

Pharma and health care, one of the areas where ChrysCapital has a high degree of expertise, is getting better with an infusion of PE money. It is also an area that touches lives directly and yet health care infrastructure is woefully inadequate in the country. PEs are accelerating the formalisation of the sector and scaling it up.

However, India does not have infinite pharma companies or hospitals worth investing in. “Also, the global mega-funds—Blackstone, Carlyle—have deeper pockets and can afford to take bigger bites. So ChrysCapital sometimes ends up sharing good deals, instead of owning them entirely,” says Sahai of Cogence. “That is why you increasingly see them explore adjacencies—education financing, selective consumer bets like Lenskart, and digital-enabled businesses.”

These are opportunistic moves, not core to the long-term strategy. But ChrysCapital has a tailwind in regulation. “Regulations (around raising capital) have changed, and are still changing,” says Ashley Menezes, partner and COO at the firm. He goes on to list the positives: “Institutional capital is 50 percent of our domestic fund. It has potential to be a lot more. Family offices will grow as well, but there are still some bottlenecks. But it is changing. The good thing is, the regulator recognises PE as a big contributor and is having those conversations with the large PE groups on what can be done to enable raising of capital.”

Growth comes from scaling up Clarus, the public markets fund, from continuing to do well in PE, and from scaling that over time in a measured way, says Shroff. “And then potentially thinking of areas where we have a right to win within the broader alternative space. That is the longer-term journey for us.”

ChrysCapital has built its reputation on deep domain expertise. But it needs to evolve from being a pure-play PE fund into a broader asset manager, says Sahai. “The natural next step for them is private credit. They should also look at hybrid return profiles, more control and buyouts. They also must diversify geographically.”

Within ChrysCapital, the partners agree evolution is necessary, though abrupt shifts are unlikely. “We will keep learning from our mistakes and other people’s successes, and evolve,” says Shroff.

Manufacturing, once an occasional bet, is back on the table as India gains global tailwinds. “We are working along those lines,” says Shroff. He, however, adds: “It won’t be any major shift between one fund and the other, but changes based on our learnings.”

Kukreja strikes a more ebullient note. “I hope over the next 10 years, India and Indian institutions discover PE, just the way they did equity in the previous 10,” he says.

First Published: Dec 16, 2025, 16:37

Subscribe Now