According to TeamLease, the manufacturing sector employs about 11.4 percent of India’s workforce, while the construction sector accounts for around 13 percent. In comparison, gig work constitutes 2-3 percent the country’s total workforce, but is playing an increasingly important role by offering flexible job opportunities, quick absorption for young and migrant workers, easy payments, and low or no skill requirements. According to Niti Aayog, India’s gig workforce is expected to reach around 2.35 crore by 2030, with roughly 20 lakh new workers likely to be added in 2026.

The gig economy allows workers to complement formal-economy jobs, such as entry-level employment in the MSME sector, with most delivery partners also signing up on multiple quick commerce platforms. For instance, according to Deepinder Goyal, CEO of Eternal, the average Zomato partner worked “38 days in the year and 7 hours per working day,” with only “2.3 percent of partners” working more than 250 days annually.

The gig economy, explains Balasubramanian A, senior vice president, TeamLease Services, “has moved beyond simply absorbing unemployment and underemployment to becoming a structural driver that has increased the national Labour Force Participation Rate [LFPR].” This absorption acts as a "formalisation bridge", he says, capturing workers who might otherwise remain in the informal economy and raising India's LFPR from 49.8 percent in 2018 to over 60 percent at present.

Also Read: The 10 minute question: Innovation or an unnecessary hazard?

How 10-minute deliveries work

A day after the delivery workers’ strike, on January 1, Goyal defended the 10-minute delivery model, claiming that it relies on the density of dark stores in given areas and short-distance routing, rather than speeding delivery workers.

“Our 10-minute delivery promise is enabled by the density of stores around your homes. It’s not enabled by asking delivery partners to drive fast. Delivery partners don’t even have a timer on their app to indicate what was the original time promised to the customer,” Goyal wrote in a series of posts on X. “Delivery partners are not overworked on our platforms.” Goyal added that Blinkit’s average delivery distance in 2025 was “2.03 km”, with average speeds of about “16 kmph”, which is similar to food deliveries that take longer.

Paytm founder Vijay Shekhar Sharma echoed Goyal, likening quick commerce to a proximity-based service rather than a race against time. “I wonder why people don’t get this? It’s like calling a car which is near you/10 mins away,” he wrote on X, adding that the model functions as a modern, tech-enabled assembly line for service delivery.

![]()

At the centre of this assembly line sits a piece of infrastructure most consumers never see: The dark store. These small, tech-enabled warehouses are designed for sorting, packing, and dispatching online orders at high speed. Every element of a dark store is built for efficiency—from high density inventory layouts to warehouse management systems (WMS) that guide workers in real time.

These warehouses are optimised for volume and speed. Fast-moving items are stored closest to the dispatch zone, while slower-moving goods are placed deeper inside. Each item is tagged, scanned, and tracked, enabling platforms to maintain detailed visibility across inventory and fulfilment requirements.

Sanjeev Bikhchandani, founder of InfoEdge and an early investor in Zomato, also weighed in on the debate, urging critics to examine how close these dark stores are to residential areas. “In my case it is 400 metres. That is how I get the delivery in under 10 minutes. The riders are not forced to take risks. Very often they are on transport that cannot go at speed and very often they do not even go onto a main road,” he wrote on X.

However, specialists in the labour sector caution that designing speed out of the delivery layer does not automatically neutralise the risk that workers face while operating in a highly competitive, capital-driven ecosystem. Kamal Karanth, co-founder of staffing firm Xpheno, says, “De-risking working conditions, in the context of quick commerce platforms, would mean changing their business models and losing edge against competition. In an aggressive, funded startups ecosystem, it will be a huge ask to slowdown to safe operating levels,” He adds that safeguards or structural changes can only come in the form of government-regulated and monitored speed and timeline promises. “Given the scale and spread, this would also be a huge undertaking to ensure businesses operate within prescribed 'speed limits' in their operations.”

In his pushback against criticism of 10-minute deliveries, Goyal highlighted that, “In 2025, average earnings per hour (EPH), excluding tips, for a delivery partner on Zomato were Rs102,” up from Rs 92 in 2024. He added that if a partner works “10 hours/day, 26 days/month, this translates to about Rs 26,500/month in gross earnings,” or roughly Rs 21,000 after fuel and maintenance costs. These earnings include “total hours logged in, including the time when the partner might be waiting to receive an order”.

Compared to the earnings of delivery workers, the Central Government’s minimum wage for unskilled workers (construction, sweeping, cleaning, loading/unloading, housekeeping, etc) is Rs 783 per day; in an 8-hour workday, this translates to Rs 95–100 per hour.

“Income levels alone are insufficient because gig earnings can be attractive in peak periods but volatile month-to-month; therefore, income stability and predictability matter as much as headline pay,” explains Balasubramanian. Hours worked and work intensity are equally important, as many gig workers compensate for variable pay by extending working hours, which affects sustainability and well-being.

The case against 10-minute deliveries

The ongoing debate also raises the question about the necessity of 10-minutes deliveries. “‘Ultra-fast’ is the real problem. We must not make unrealistic and unwanted promises and then push an entire work system to hustle relentlessly,” says Chandrasekhar Sripada, clinical professor (OB), Indian School of Business. “Yes, an ambulance or emergency health care should ideally reach in 10 minutes, but not ice cream or a beauty product.” He strongly feels there is no point in creating such business models and then trying to adjust them to address safety and welfare.

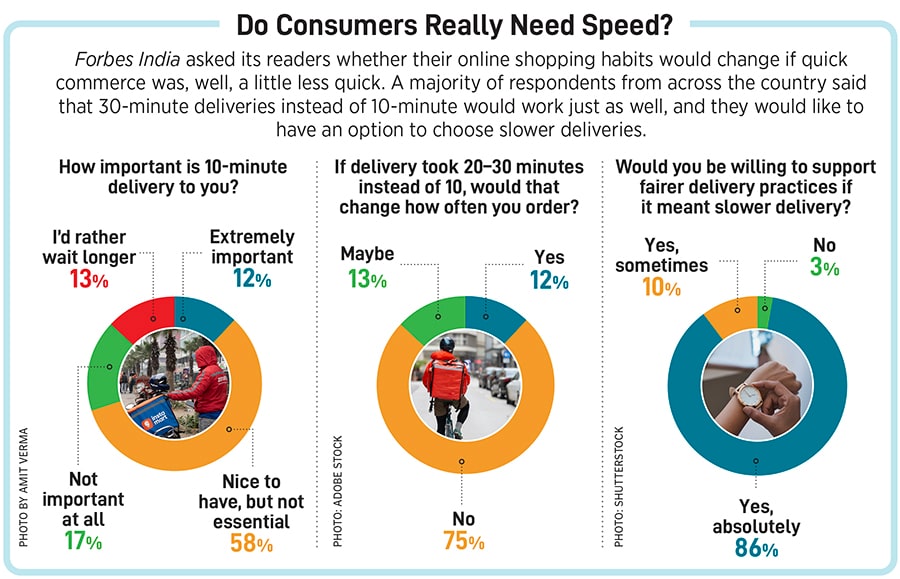

A Forbes India survey asked consumers if they really need 10-minute deliveries: 58 percent of respondents said such deliveries were “nice to have, but not essential”, while 75 percent said they would not change their frequency of orders if deliveries took between 20 and 30 minutes, instead of 10 minutes.

Naveen Malpani, partner and consumer and retail industry leader at Grant Thornton Bharat, believes in the evolution of a hybrid model that distinguishes between urgent deliveries and non-critical ones: “Ultra-fast fulfilment will remain relevant for urgency-led, high-velocity missions, while slightly longer and more predictable delivery windows support broader assortments and higher basket values. The long-term opportunity lies not in universally compressing delivery timelines, but in using immediacy to unlock deeper, more valuable consumer baskets.”

At present, workers in the 10-minute delivery ecosystem report pressures that stem from the way earnings are structured; there is anxiety arising from income volatility, since earnings are directly linked to number of hours worked, individual effort and platform incentives. But there is uncertainty at every level, because incentives are dynamic, algorithm-driven and influenced by market conditions.

That said, there is increased flexibility in scheduling work hours on some platforms. Madhav Krishna, founder and CEO of Vahan.ai, says, “Earlier, particularly in delivery services, workers were often expected to commit to full-day or eight-hour shifts. Today, most platforms operate on slot-based systems, allowing workers to choose two- to four-hour shifts, which provides greater flexibility.”

He adds that workers who operate across multiple platforms align their work with peak demand periods. For instance, they may work in the bike taxi sector during morning commute hours, and then shift to e-commerce deliveries in the afternoon, and food deliveries in the evening. “Such workers can earn Rs 50,000 to Rs 60,000 or more per month. From this perspective, flexibility within the gig economy has demonstrably expanded,” he explains.

However, ground realities may be quite different. Factors such as incentives being based on face-less algorithms, peak-hour requirements, and acceptance-rate pressures can limit any real choice that workers can have over when and how much they chose to work. For workers, flexibility is meaningful only if they can earn predictable income without being forced into longer or less desirable hours. “The response is not to dismiss flexibility claims, but to redefine flexibility as a balance between real choice, earnings predictability, and worker protections,” Balasubramanian says.

For a large share of workers, particularly food delivery workers, gig work functions as supplemental income rather than a primary source of livelihood. Bornali Bhandari, professor at National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER), says, “For 50 percent of the workers, it was always income supplementation. It was never a full-time livelihood.”

A study by Bhandari and her team found that workers who feel high stress levels, didn’t experience any career growth or progress, and faced difficulties in changing their delivery zones were more likely to exit the platform. However, “workers who joined the platform due to higher income, flexible work/hours, flexible seasons and previous job loss were more likely to stay in the platform.” The study also found that skilled workers eventually tend to opt out of platform-based gig work, and treat it as a stop-gap arrangement. Consequently, as NCAER found, a worker stays with a platform for an average of only 14.3 months.

Regulations and social security

The Code on Social Security (CSS), 2020 extends social security coverage to gig and platform workers—categories that sit outside traditional employer-employee relationships but perform services coordinated through digital marketplaces. The CSS tasks the central government with framing social security schemes to provide benefits, including life and disability cover, accident insurance, health and maternity benefits, and old-age protection. “The Code also provides for setting up of a Gig and Platform Workers’ Social Security Fund, and notified aggregators’ contribution to the fund shall be between 1 and 2 percent, as maybe notified by the central government, of the aggregator’s annual turnover,” says Krishna Shah, advocate, Gujarat High Court.

The National Social Security Board, which will be set up under CSS, is tasked with monitoring the administration of such schemes. However, “this board, will be made up of five representatives of the aggregators as well as five representatives of the gig and platform workers as the central government may nominate,” adds Shah.

The question that remains unanswered is, who will pay for these benefits? “It is likely that the financial burden will be shared by consumers and the government, as most platforms operate with limited margins; platforms may contribute partially. The sustainability of this model will depend on how these costs are distributed,” says Krishna.