Why IPOs present more than an exit opportunity for startup investors

The recipe for investors to exit startups in India and book returns has acquired a distinctive desi flavour, seasoned by initial public offerings

New York-based Tiger Global, egged on by its star executive Lee Fixel, first invested in Flipkart in 2009, when it was still an online bookseller. The valuation was $42 million. Over the next eight years, Tiger’s investment in the Indian startup rose to $1.2 billion.

When Walmart acquired 77 percent equity in Flipkart in 2018 for $16 billion, it renewed venture capital (VC) investors’ faith in India as a land of returns. This faith had begun to waver because no VC had made much money from Indian startups by that time. And Flipkart itself, about 18 months before the Walmart deal, was seen as a company cowering under the heat of competition from Amazon.

However, the Walmart-Flipkart deal as well as the subsequent turn of events have made investors realise that India is charting a distinctive course that VC firms are still coming to terms with. The VC playbook, as drafted in the world’s most developed startup ecosystem, the US, says nine out of 10 investments would fail. But the 10th, the one to succeed, will give such a high return—90- to 100-times the investment—that it would make up for the failures.

That is not what is happening in India. For instance, Tiger, by the time it fully exited Flipkart in 2023, walked away with cumulative proceeds of about $5 billion.

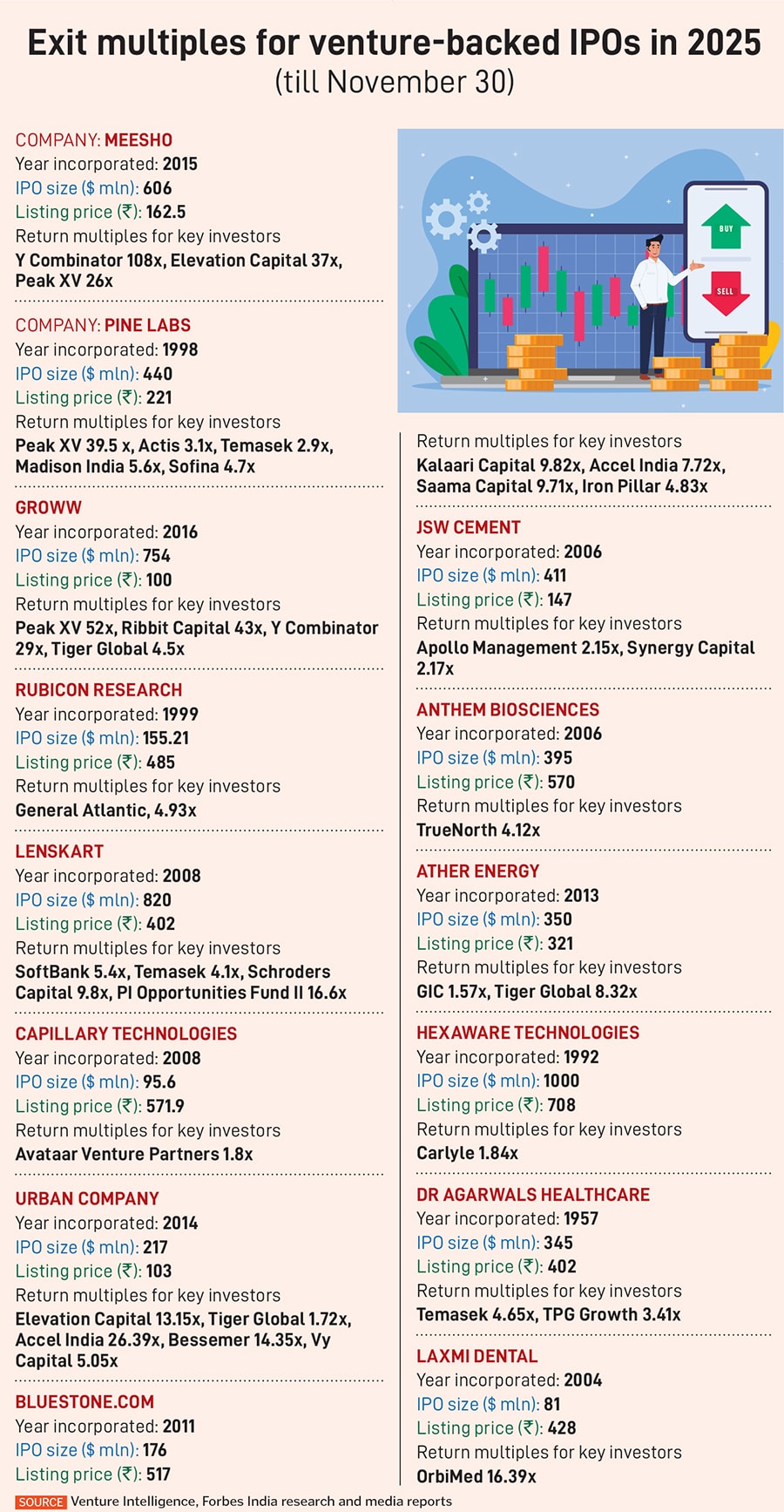

Indeed, the last few months have seen impressive returns for VCs from Indian startups. Pine Labs reportedly gave Peak XV 39x returns. Accel India is said to have made 29x returns from Urban Company. Elevation Capital made 37x from Meesho and 19x from Urban Company.

If you look elsewhere, the x figure tapers off. And one more thing: The returns in Pine Labs, Urban Company, and Meesho were realised during their initial public offers, or IPOs.“A large number of exits [in India] have happened through IPOs, whereas in the US, in tech, probably 70 to 80 percent of exits happened due to sales to strategic or mid-market private equity, which is not yet a well-developed ecosystem in India for the tech industry,” says Anuj Bhargava, managing director-India at Lightspeed India Partners. He points out that the bar to IPO in India is slightly lower compared to what the market expects in the US. “Unless you are a $500 million company in the US, you cannot even think of an IPO. In India you can IPO at one-fifth or one-tenth the size.”

The impetus for startup IPOs also comes from the Securities and Exchange Board of India. The markets regulator last year tweaked rules governing employee stock options and compulsorily convertible securities to encourage startups to list in India.

“Indian public markets allow listings at valuations as low as about $700 million, unlike the US, where companies often need valuations around $10 billion to attract research and analyst coverage. As a result, US companies valued at roughly $6 billion often pursue M&A for exits. India’s lower threshold reduces the incentive to sell and enables companies to raise public capital instead, while giving investors an exit path beyond limited M&A activity,” explains Ashutosh Sharma, head of India ecosystem at Prosus.

Eighteen new-age technology companies made their public market debuts in 2025. The momentum is likely to continue in 2026, with big names such as PhonePe, Razorpay, NSE, boAt, and others awaiting their turn.

These new-age tech IPOs are different from the first wave led by the likes of Eternal (previously known as Zomato), Nykaa, Delhivery, and others between 2021 and 2023 in terms of the time taken to list on public markets as well as the greater emphasis on profitability being showed in the runup to the more recent floats.

In a market where liquidity for investors through mergers and acquisitions (M&A) is sparse and secondary transactions are feasible only for early-stage investors, public market listing has emerged as the chosen option for ringing in the right returns. Early-stage bets by venture capital firms Accel India, Peak XV, Elevation Capital, and Lightspeed India Partners have recorded multi-bagger exits in 2025.

For startup entrepreneurs in the fray, IPOs present more than an exit opportunity; they have become a means to raise capital at better valuations, in addition to creating a national brand. Take, for example, coaching and test prep platform Physics Wallah, which made its public market debut in November 2025. Ahead of the listing, co-founder Prateek Maheshwari had told Forbes India that the decision to target the public markets was founder-driven.

“We are a hyper-growth cash-generating company and started preparing for a public listing in September 2024. We wanted to list while young to share our growth with retail investors. Being a listed company gives us an opportunity to become a pan-India brand across multiple languages and geographies,” Maheshwari had said.

The company, founded in 2020, is an exception; the bulk of the startup IPOs in 2025 was of companies with 10 to 15 years’ vintage, offering liquidity to early and growth investors. Of the ₹3,480 crore Physics Wallah raised from retail investors, only ₹380 crore made up the Offer-for-Sale (OFS) portion, in which the founders sold their shares, while no investor sought an exit. The remaining ₹3,100 crore was fresh capital raised by the company to power its growth.

However, there were other listings in 2025, such as of Lenskart and Groww, where the OFS made up for nearly 70 percent and 84 percent of the issue sizes. These numbers show the difference between companies tapping the public markets for growth capital, such as Physics Wallah and Meesho, and the profitable hyper-scalers such as Lenskart and Groww, where the opportunity is used to give an exit to investors on the cap table.

Also Read: Warburg Pincus in India recalibrates its PE strategy

A clear shift in the way markets operate and the macroeconomic conditions have made the Indian public markets attractive over the years.

“The supply of large-scale technology companies has increased as companies founded in the 2014-15 wave have scaled for an IPO. On the demand side, public markets are now receptive to these types of companies, which might not be profitable. Third is the growing domestic investor base, which has made capital available for more public listings,” says Abhinav Chaturvedi, partner at Accel India.

Companies listing in the public markets in India today are no longer dependent on foreign institutional investors (FIIs). FII flows into Indian markets have been volatile over the last three years due to global economic developments, while the share of domestic institutional investors (DIIs) such as mutual funds, insurers and banks has picked up. According to recent exchange data, DIIs invested about ₹7.1 lakh crore in Indian equities in 2025—up 35 percent from 2024.

According to data from Prime Database, mutual funds (MFs) have invested around ₹22,750 crore in initial public offerings (IPOs) in 2025, accounting for nearly 19 percent of the total ₹1.22 lakh crore raised from the primary market this year. The increase in investment was nearly 12 percent from the contribution of ₹20,351 crore by MFs in IPOs in 2024—a historic high.

The rise in digital distribution and India stack tools like Aadhaar-linked KYC make it easier for retail investors to participate in IPOs. These factors contribute to the robustness of Indian public markets.

“Investors are looking at where the alpha will come from. This is driving interest in the tech story. If you look at US public markets, technology companies are a large part of the market cap. In China as well, tech is becoming substantial. In India, all the new-age technology companies put together make up a small part of the public market cap, but this segment is growing rapidly. As more VC-funded companies scale and go public, tech market cap will continue to grow,” says GV Ravishankar, managing director at Peak XV.

Given the buoyancy in Indian public markets, IPOs are the best-case exit scenario for investors in a country where the M&A ecosystem is yet to pick up speed and secondary exits are just about starting to grow.

“Across the 18 mainboard new-age tech companies, which went public in 2025, the ratio of OFS to fresh issuance was 55 percent to 45 percent. It is not disproportionately skewed and depends on the cycle the company is in,” says Akshay Gupta, director at corporate advisory and investment banking firm, Prime Securities.

Gupta compares the IPO structures of wealth tech platform Groww and value-commerce platform Meesho. “Groww is a market leader, hugely profitable and scale, with more than 10 million users. It does not need more cash to continue on its growth path and that was obvious from the bulk share of OFS in its issue size,” he says. In contrast, Meesho, despite being a market leader, needs more capital to grow and turn profitable and revised its OFS, reducing it to only 20 percent of the total issue size ahead of the listing.

“Yes, OFS is also a function of funds coming to an end and therefore needing to exit, but that can be achieved through secondary sales in follow-on rounds or by selling to a private equity investor,” adds Gupta. He says the trend is likely to continue in 2026, as long as Indian public markets continue to offer robust returns.

Typically, an early-stage investor would exit to hedge funds, sovereign funds, pension funds and growth arm of private equity (PE) funds. Closer to IPO, large family offices, pre-IPO funds and wealth platforms offer liquidity opportunity to early investors, says Bhargava of Lightspeed India.

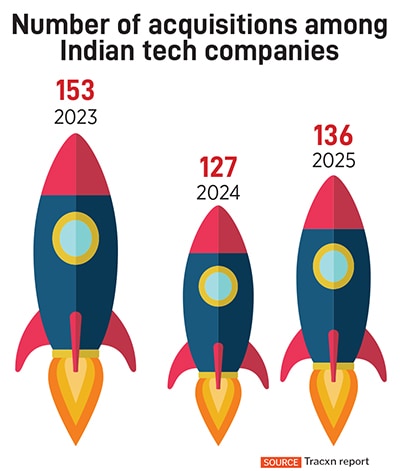

“M&A as a method to exit hasn’t been very active in India historically, though the trend is now changing. Traditional buyers in India such as large conglomerates have a different lens of looking at new-age companies. However, there are large Indian technology companies and global strategics who are also potential buyers,” says Bhargava. When you have a well-functioning M&A market, along with well-functioning capital markets, he says, is when you can call it an evolved ecosystem.

This leaves secondary transactions and public listings as other options for exit for venture capital (VC) investors. Secondary transactions or secondaries are transfer of ownership of existing stocks between a seller (in this case investor) and buyer (new investor, who is joining the cap table) without changing the company’s balance sheet or issuing new shares. However, a common complaint against both avenues remains that these take time to execute, and in both cases, the buyer often expects a discount on the valuation.

“There are companies where secondary funds are willing to pay a premium for a position ahead of the IPO but these are the sellers’ market and fewer in number,” says a growth investor on condition of anonymity. He adds that acquisitions in the Indian markets often take many quarters to a year to close, especially between domestic firms.

Over the last year, multiple technology startups, including Flipkart, Groww, Pine Labs, Razorpay and PhonePe, have moved back domicile to India, driven by regulatory reforms, and to tap into the domestic public markets. One of the key reasons is the lower entry barrier compared to its peers in the US.

According to private company data and analysis specialist Venture Intelligence and other estimates, the average IPO size for VC- and PE-backed technology companies in 2025 stood at approximately $426 million. However, returns from IPO events are also lower compared to their US peers. “The absolute size of some winners in the US is different from that in India, as is the median size of equity offering from the companies going public. The size of the entry cheque in Indian companies is also lower, and India has seen some good exit outcomes,” says Bhargava of Lightspeed.

Sharma of Prosus adds that the Indian tech IPO market is younger compared to the US, lacking decades of compounding businesses, and thus the post-IPO upside in these two regions are not comparable.

“Not all companies that are listed have predictable performances,” observes Ravishankar of Peak XV.

He adds that startups are sometimes not prepared for life as a publicly listed company and end up treating public markets like private markets. In these situations, business predictability becomes key and scale is important to ensure analyst coverage and access to larger public markets investors.

“We have just started witnessing tech startup IPOs in India and VC funds are still working on improving their playbooks to support companies as they transition from private to public. Most importantly, going public is a milestone, not a destination… it is practically an irreversible step,” says Ravishankar. He adds that public markets need predictable execution and no negative surprises. “We have seen 20-plus companies in our portfolio go public in the last five years, but that’s only a subset of the companies that want to go public.”

Peak XV asks its portfolio companies whether they have predictability of revenues and earnings in their businesses.

Second, they have to be comfortable with the idea of facing public scrutiny and hard questions.

Third, founders should have the maturity to focus on building for the long term instead of worrying about short-term stock performance. VC firms often end up creating separate teams to handhold entrepreneurs in their portfolio through the process of preparing for the outcomes.

Often startups preparing for an IPO are blindsided by the amount of paperwork and diligence required to set their house in order. Prashant Gupta, partner and national practice head-capital markets at law firm Shardul Amarchand Mangaldas & Co, says these processes require 12 to 24 months.

“Companies do not realise the amount of effort it takes to do an IPO, the documentation needed, or financials and audit which are different from regular audits,” says Gupta. “There is also the question of founder incentives, which takes a long time to sort out. Often it can derail the entire IPO process because what the founder expects versus what the investors are willing to give are completely different. So, when companies come to us 12 to 24 months ahead of the IPO, we can help them prepare better.”

“Indian founders over the last year have shown that they can build enduring, disciplined businesses leading to companies with fundamentals strong enough to go public and perform in the markets. The recent wave of listings has been shaped by founders who prioritised sustainable growth, realistic valuations and governance built for scale, which is why public-market reception has been strong. More such mature, long-term companies are now coming through the pipeline,” says Anand Daniel, partner, Accel.

According to him, the momentum is only just beginning. “Globally, IPO activity is one of the highest in India today, and Indian startup IPOs will take an even bigger share of global listings going forward,” he adds.

First Published: Feb 09, 2026, 17:47

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Feb 06, 2026 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)