Stem Cells Industry: The Battle Within

Fearing that unscrupulous use may hijack this promising field, stakeholders are racing to regulate its applications. Are they swift enough?

“We don’t do clinical trials, we provide commercial stem-cell therapy,” says an executive of a Pune-based company on the phone when we inquire about participating in one to avail the treatment that its website boldly speaks of. “If you can’t come in person, send us your case study in email and we’ll advise you how many infusions of stem cells your patient would require,” he suggests.

The company’s website says it has provided 1,000 infusions to patients and is a ‘leader’ in stem-cells ‘therapy’. The so-called therapy costs upwards of Rs 2-3 lakh, the executive discloses on persuasion.

This Pune clinic is only one among the many that peddle the unproven stem-cell therapy. They are supposed to enrol patients under a proper clinical trial instead they get by with merely adding the word ‘experimental’ to their offerings. You won’t find these clinics on the clinical trial registry of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), where they must enlist.

Now, contrast this liberally-delivered, unregulated treatment with what Stempeutics Research in Bangalore is trying to do. For seven years, the startup, promoted by the Manipal Group and led by chief executive BN Manohar, has been at the bench studying stem cells in its labs in India and Malaysia. With a series of clinical trials, government approvals, 24 patents, 41 journal publications and Rs 125 crore in investment, the company is finally close to launching one of its three—the least regulated one at that—stem cells-based products in 2013.

These two starkly opposite sides of how this new field of regenerative medicine is developing in India point to two problems that could derail the entire thing:

1. Regulatory hurdles that hit the growth of a nascent industry: The science behind it is advancing rapidly and the medical and commercial prospects are so promising that experts fear the regulatory gaps and delays are hurting the level playing field for entrepreneurs and investors who are fleeing to countries like Malaysia and Singapore. (While it takes just 60-90 days to get regulatory clearances in Malaysia, it may take 12-18 months in India.) Says Nitin Deshmukh, chief executive of Kotak Private Equity and an executive member of the biotech industry body, ABLE (Association of Biotechnology Led Enterprises) council: “Many of our companies are shifting their research and development and IP registration to Malaysia and Singapore. They even want to license outside India.” Visibly angry and disappointed, he says he has stopped investing in life sciences companies as they have no future in India. “Clinical trial is the bedrock of this industry if that is not streamlined how will companies progress?”

Says Nitin Deshmukh, chief executive of Kotak Private Equity and an executive member of the biotech industry body, ABLE (Association of Biotechnology Led Enterprises) council: “Many of our companies are shifting their research and development and IP registration to Malaysia and Singapore. They even want to license outside India.” Visibly angry and disappointed, he says he has stopped investing in life sciences companies as they have no future in India. “Clinical trial is the bedrock of this industry if that is not streamlined how will companies progress?”

The regulatory gaps and delays in life sciences have come to such a frustrating state that ABLE has sent a representation, rather an SOS, to the government in the new year.

2. The sector could lose credibility: Experts also fear if someone were to file a PIL against the unregulated use of stem cells and if judicial activism were to set in, as it has in agriculture with genetically modified crops, regenerative medicine in India could get snuffed out.

The only reason it has not blown up as a major health care problem or come under greater public scrutiny is because in most cases the therapies offered are not harmful in the short term, says Dr Alok Srivastava, head, Centre for Stem Cell Research at Christian Medical College in Vellore. But for a biological ‘drug’ that isn’t metabolised or excreted from the body, long-term monitoring is critical, as cells keep multiplying.

“Patients are administered some cells and asked to wait for response, which almost never comes if scientifically evaluated, but only a few have come to any significant harm,” says Dr Srivastava. “The real problem will come if there are many unexpected adverse effects which will bring disrepute to the field and reduce the support to this science from the community.”

KNOCKING AT THE POTENTIAL

At the Stempeutics Research facility in Whitefield, Bangalore, Manohar holds two sample vials in his hands. They look like regular injections except that instead of a drug, they’d contain millions of stem cells when they are eventually shipped to hospitals and clinics for use.

The company started out in 2006, a few years after embryonic stem cells arrived onto the international biomedical scene with a splash, only to go down a sobering path when US President George Bush stopped federal funding on moral grounds. By then, adult stem cells were showing promise and Stempeutics chose that route. It uses a type of cells from bone marrow, called mesenchymal stem cells, which can grow into different types of cells, to develop an off-the-shelf product. The product, called Stempeucel, is currently undergoing phase two trial for three diseases: Osteoarthritis, critical limb ischemia (CLI, a condition that restricts blood flow to the limbs and causes acute pain) and liver cirrhosis, a chronic liver disease caused by alcoholism.

Of these, the CLI study is under fast track as the government is also keen to bring such a product to the market. “It’s an open label study so we can see the outcome I can tell you that we have terrific results,” says Manohar. The final phase of most of these studies will be completed in 2013 and by end 2014 or early 2015, Stempeutics plans to roll out its products.

It is the only company in India which has adhered to all national and international protocols and has a credible product pipeline, says Satish Totey, chief executive of Kasiak Research in Mumbai, a holding company of Bharat Serums & Vaccine. Totey was one of the founding members of Stempeutics who also set up its Malaysian unit. Three years ago Totey returned to Mumbai to set up Kasiak, which is developing products and services in the same field.

Incidentally, Kasiak is following a strategy similar to Stempeutics’: To escape the regulatory delays, the company is now shifting much of its work, including contract manufacturing of cellular products, to Malaysia.

“I am burning Rs 80 lakh per month in India the promoters have already invested Rs 25-30 crore. I need to invest another Rs 30 crore before Kasiak can get some revenue,” he says. “Look, it’ll be 10 years before Stempeutics finally starts earning decently.”

But Stempeutics’ investors have been patient, with their eyes on the long term. They brought Cipla as a strategic investor in 2009, which has infused Rs 60 crore so far and holds 49 percent stake. This has helped, but the startup needs an additional Rs 75 crore of investment till 2015. By then, it expects the revenue to kick in. The global market is also expected to mature around that time. Just one product, say, for osteoarthritis, could open up $100 million worth of market every year for Stempeutics, estimates Manohar. Some 30 percent of people above 60 years of age suffer from osteoarthritis, most of whom get prescribed knee replacement.

Cutting edge as this field may be, Manohar believes keeping it affordable will be key to its adoption.

“For all our products, we’ll target a price that is certainly a third or a quarter of what multinationals would offer and/or is half the cost of standard care,” he says. If knee replacement today costs Rs 2.5-3 lakh, Stempeucel treatment would restrict itself to about Rs 1.5 lakh.

But before he gets there, he wants to commercialise products that have a shorter and easier regulatory path. One is an anti-ageing/anti-wrinkle cream, Stempeucare—an over-the-counter product, which it is developing with Dabur. The second is a device, Stempeutron, to make on-demand stem cells to be used in various cosmetic or reconstructive surgeries. (At least 1.2 lakh breast augmentations take place in India every year.)

The device is Manohar’s pet project. An engineer who spent 12 years in GE before coming to Stempeutics, he knew that the company needed to tap the autologous stem cells (using person’s own cells) market as well. A point-of-care device that takes one’s fat tissues and gives a cocktail of cells to be injected back into the person for reconstruction is a step in the direction that medical science is moving—that of personalised medicine.

In all likelihood, Manohar will succeed in grossing some revenue until the killer-app kicks-in in 2015, but his urgency for regulation is visible. “While we work till science matures, others [stem cells clinics] are making money from day one,” he says. He gets requests from many “VIPs” for stem cells that he politely declines, he says.

Manohar’s refusal is rooted in science it just isn’t ready yet.

THE DEPTHS OF THE PROBLEM

In October 2012, Shinya Yamanaka shared the Nobel Prize with John Gurdon for the discovery that adult cells can be converted to stem cells—thus, laying the foundation of regenerative medicine. In his first interview after the ceremony, Yamanaka cautioned the world to not fall for stem-cells therapies offered by rogue clinics in countries like India, China and Russia. As if in a well- (or ill-) timed move, a multi-speciality hospital in Bangalore invited the press to announce it was already offering a “world class” therapy for advanced vascular necrosis (where restricted blood supply causes bone death) and paraded a few patients.

Srivastava says the question to ask is: Have these claimed successes been medically tested by independent physicians? “Personal testimonies are not scientific data and this distinction needs to be made when reporting these stories,” he says. (Some clinics, like Geeta Shroff’s NuTech Mediworld in Delhi, are beginning to understand this read end part of the story.

“Its clinical use has become explosive in India, and is already going out of hand. Our [regulatory] system has been very slow,” says Polani B Seshagiri, professor at the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore and in-charge of its stem cells laboratory. What you get in the country currently is not yet stem-cells ‘therapy’. Strictly speaking, it is ‘clinical trial’ and anybody offering it ought to follow the rules of a trial, he says. Seshagiri has been on various expert committees of the ICMR.

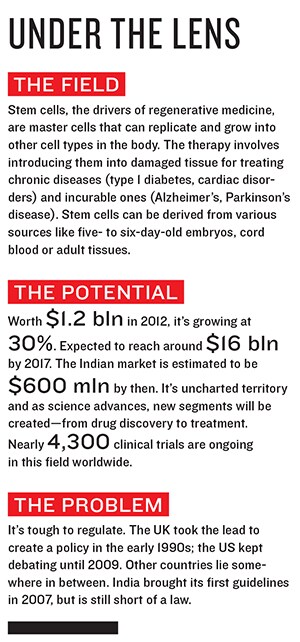

“There are dozens of clinics and hospitals offering yet-to-be-proven therapies even advertising them on SMSes we are aware of that,” admits an ICMR official. But, in the absence of a law, the loopholes of the existing guidelines are routinely exploited. (India brought its first guidelines in 2007, but is still short of a law.)

In reality, it’s more complex than that. Cell therapy is in a category of its own and cannot truly be equated with drugs or organ transplants. Therefore, the current laws are inadequate, says Srivastava.

Moreover, under the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association, physicians can offer unproven treatments if other options have been exhausted. Though a long compliance list accompanies such decisions, they are hardly adhered to by clinics that offer these as commercial treatments.

Between the huge unmet human need for treatment of incurable diseases and the hype around the possibilities of these therapies on one side, and the opportunistic and unscrupulous physicians exploiting the situation on the other, good science struggles to move forward, says Srivastava. “In India,” he says, “the problem is compounded by the relatively unregulated state of the health care system itself.”

But now, different agencies seem to be racing to stop exploitation of vulnerable patients.

“Even as you go to press, the process of registration of clinics and institutions using stem cells is on,” says Srivastava. “We will also proactively approach those who advertise their services and successes and ask them to be registered and report their activities,” he adds. Srivastava chairs the recently formed National Apex Committee on Stem Cell Research and Therapy (NAC-SCRT), which is working with the Medical Council of India and the Drug Controller’s office, the two agencies with executive powers, to bring cell therapy under regulation.

CUTTING THROUGH THE HAZE

In the midst of all this, a national taskforce has revised the 2007 guidelines, particularly to accommodate the science and technique that Nobel laureate Shinya Yamanaka demonstrated—a mechanism by which any adult cell is turned into near-embryonic stem cells, called induced pluripotent stem cells. These guidelines have been framed after holding public debates in five zones of the country. It’s certainly an improvement as Britain has shown how consistent dialogue with the public about the developments, challenges and uncertainties in stem-cells research make legislation more acceptable.

In the UK, a strong regulatory system has encouraged inward investment, reduced risk and supported the development of regenerative medicines well, says Stephen Minger, global head of research and development for the cell technologies business of GE Healthcare Life Sciences. An advocate of early regulation, Minger, who has also worked in various medical schools, relocated from California to London when the US stem cells environment became uncertain. In 2009, he joined GE when he thought the time was right for commercialisation.

In yet another pioneering step, he says, the UK government set up an agency called Cell Therapy Catapult in 2012 to bridge the gap between business, academia, research and government. Once established, funding for the Catapult will come from business-funded R&D contracts, collaboratively applied R&D projects funded jointly by the public and private sector, and core public funding, says Minger. He has been closely associated with Indian institutions and believes the UK model can be replicated (as it has been in Australia and Canada) so that the international marketplace is regulated and the “reputation of regenerative medicine is not compromised”.

In the next few weeks, the 2012 guidelines will be sent to the ministry of health for legislation. The logical agency to regulate the sector is the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization through the Drugs Controller General of India (DCGI). But since they do not have adequate capacity or expertise, a new committee has been established under it, called the CBBTDEC, to process cellular therapy-related applications.

“To provide a path for progress with clinical stem-cells research in India during this period when the regulatory agency develops expertise and capacity and single path gets established, the ICMR and DBT, which have funded most of the academic clinical studies, have developed alternate paths for their review and approval based on the existing guidelines,” says Srivastava. The privately sponsored studies also follow a similar path through the DCGI and ICMR.

It is up to the government how it wants to enforce the guidelines, says VM Katoch, director general of ICMR, who also heads CBBTDEC. He has a short-cut solution though. It can be done swiftly if within the existing laws responsibilities are assigned to the Medical Council and the Drug Controller the former can regulate the procedures in hospitals, the latter can regulate products. (It’s another matter though that the MCI has never penalised any doctor or hospital.)

As a first step, all clinical trials are being registered on the ICMR registry. (http://ctri.nic.in/Clinicaltrials/login.php). The idea is to inform people, who choose to try this experimental treatment, to look up this registry and ensure the legitimacy of the clinic.

This is needed as there’s chaos all around, says Totey. “You only need to look at the last few pages of local papers like Mumbai Mirror, which are full of advertisements for stem-cells therapy.”

If 2012 saw approval of the first two stem-cells drugs in Canada and Korea, 2013 is likely to see even more advances. A speedy regulatory regime is the only sustainable competitive advantage that India can offer to companies and researchers.

“Clinical trial is the bedrock of this industry if that is not streamlined how will companies progress?”

**********************

Controversial Medicine

Working with the scientific community and peer review is the only way to get credibilityAt NuTech Mediworld in south Delhi, Geeta Shroff sits amidst a bunch of blue and green books—self-published case studies of the nearly 1,100 patients she has treated with embryonic stem cells in the last 10 years.

An infertility expert with access to embryos, Shroff jumped into stem-cells adventurism much before guidelines for stem-cells research (or therapy) were in place in India. In 2013, as she waits for her patent to be granted in some of the regulated markets, she is preparing for the brutal world of peer-reviewed publication.

“I want my technology to be part of mainstream medicine,” she says. “I also want to license my technology for producing off-the-shelf embryonic stem-cell products.” This looks improbable. It would have required systematic clinical trials, preceded by pre-clinical animal studies, which Shroff “doesn’t believe in”.

Polani Sheshadri, who heads Indian Institute of Science’s stem cells lab, has seen some of her books. He says they don’t comprise scientific studies they are merely “compendium of information”.

Many experts say Shroff has exploited the gaps in the Indian medical regulatory system, which does not specify which agency will regulate what and who has the executive authority to penalise a company, clinic or hospital peddling these therapies.

But if Shroff wants the scientific stamp, she’d need to work with the community. That’s how medicine advances, by peer review. Or else, even her patients would skulk in doubt. Like 46-year-old Ron Bailey.

A native of California, Bailey damaged his spinal cord in an accident and has been coming to NuTech for four years, paying out of pocket for this treatment. I ask if he believes he has benefited from this therapy. He looks up from his wheelchair, unsure and uncomfortable: “I can’t say whether it is stem cells or my working harder on the physiotherapy…but I have to try unorthodox therapy, my parents are old and can’t be around for long to look after me.”

To listen to the interview with Geeta Shroff , Click Here

First Published: Feb 12, 2013, 06:10

Subscribe Now