A Different Stroke from Jeev Milka Singh

The year 2012 saw him become India's most successful golfer. Now he wants to give back

Forbes India Celebrity 100 No. 70

At the play-off hole of the 2012 Scottish Open, his position on the penultimate shot wasn’t great and his fingers and wrists were hurting. His opponent Francesco Molinari, the Italian Ryder Cup star, who had led the European Tour event for the first three days, fluffed his putt. “Drive for show, putt for dough,” they say. After the Who’s Who of golf, including defending champ Luke Donald, Phil Mickelson and Ernie Els, failed to take their chance, Jeev Milkha Singh calmly stroked his way into history, becoming the first Indian to win four European Tour events.

The &euro518,046 he won at the Scottish Open contributed a large chunk towards his 2011-12 earnings of &euro845,947 (his career earnings stand at &euro6,331,225) and shows just how far Singh and Indian golf have indeed come in the last 20 years. In 1992, says Singh’s close friend and senior golf journalist Joy Chakravarty, Indian players were happy playing for local Rs 25,000 tournaments culminating in the $100,000 Indian Open.

Singh—the first Indian to make it into the top 30—is now ranked among the top 100 golfers in the world and has many great years left on the tour. But he’s changing course. The next decade in his career is going to be about being a facilitator for golf growth in India.

Singh’s plan is three-pronged: He’s going to help nurture India’s next golf stars through a top-quality academy he wants to lend his name to golf course developments and give more and more urban Indians access to the game and he wants to continue to grow the number and stature of Asian tour events in India, giving Indian talent the chance to compete against a full field of the region’s finest.

Teeing Up the Next Generation

For starters, Singh has given out almost 40 golf sets to promising youngsters and caddies in his city, Chandigarh, over the past eight years the next couple of years will see his contribution to Indian golf go to the next level. Some of the motivation for doing this is deeply personal.

As a boy, he used to play with kids more talented than him, but they were turned away from golf by their parents because they came from business houses and were expected to join the family business. He wants to change this. His parents—Olympic athlete Milkha Singh and former captain of the Indian women’s volleyball team Nirmal Kaur—supported him, but stressed how important it is for young golfers to have an education.

Behind the scenes, he has been preparing to open a golf academy and school in Chandigarh. Following the model created by English golfer Lee Westwood, he wishes to partner with an established national school to run the academic and administrative side of things, while he would bring in his contacts and expertise to run the golf academy. Westwood’s Golf Schools are now present in the UK and the USA and offer programmes ranging from four-year residential high school options for 14- 19-year-olds to two-year diploma programmes (equivalent to A-levels) for 16-year-olds in conjunction with Leeds City College to regular weekly/weekend training programmes.

Shivas Nath, one of the founders of Evolution Golf and business development head for Nicklaus Design and academies in India, runs three golf academies in India and says that there are broadly two models an academy can follow. The simpler, low-cost route involves signing up with an existing club and introducing junior members and non-members to the game through a programme tailored to be fun for youngsters.

The second path is to create a high-end Nicklaus Academy-style finishing school which is ahead of the curve, for teenagers looking to become young professionals. These involve high-tech performance measurement gadgetry, multiple types of training surfaces and a global brand. “There have to be enough residents via homes and schools in a 10 km radius, since this is the limit parents are willing to let their children drive to pursue any activity,” says Nath. A lesson at one of the 20 Nicklaus Academies around the world costs $100. It is this model that Jeev Milkha Singh is looking to emulate.

“I want to create a place where 50 kids can come and stay, train and learn,” Singh says. “These academies require considerably more investment for land, landscaping, staff training, technology and facilities but patrons pay for the ‘signature brand’.”

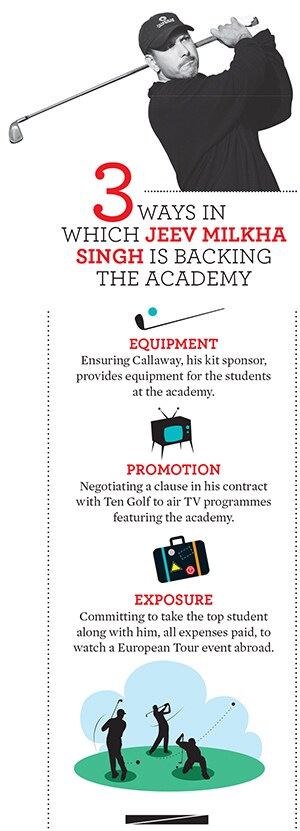

It won’t be easy, but Singh has shown he means business. He’s in talks with potential partners like the Punjab government and the Who’s Who of Indian business houses. He’s already put his weight behind the project in a number of ways.

“Besides,” says Joy Chakravarty, “Jeev is at the stage in his career where if there’s a junior tournament in Japan or the USA, he can get on the phone to the organisers and get his top three students in.” Singh has also committed to taking the entire academy to watch the Indian Open. Maybe only five of the class of 50 will get sponsors and become professionals, but he wants to make sure the others have a solid education to fall back on.Digraj Singh, a close friend of Jeev Milkha Singh’s and owner of Digraj Golf Inc, knows that pros like Westwood have powerful management teams behind them Jeev Milkha Singh will need to find the right support team. “The infrastructure investment is a big capital cost but that’s not what Jeev should be providing,” he says. “His family, especially his father, know how to raise champions and to inculcate the winning mentality. It’s the intellectual property that Jeev can provide which is incredibly rare—that’s his real investment.”

Horses for Courses

The other route for professionals looking to transition is course design and golf tourism—the Greg Norman/Jack Nicklaus route. Digraj Singh says that golf courses by themselves rarely make commercial sense. It’s only when a top player helps design one and lends his name to the real estate scheme, that the property becomes valuable.

A world class golf course means hotels, resorts, housing and other real estate development nearby. The course at Unitech Grande in Noida, designed by Norman, is the centrepiece of some 90 residential towers, for example. Jeev Milkha Singh designed the Kensville Golf Course, 40 km from Ahmedabad, which is seeing rapid growth: The fifth phase of plot-planning is already in the works! It is a path he’s looking to explore further.

The premium attached to living near a golf course is considerably higher in India than other developed countries. “In the US, close to 70 percent of home buyers on golf course developments are non-golfers. In India that number is 95 percent,” says John Cope, who has been developing golf courses around the world for 30 years and was the lead designer for the first Nicklaus Design golf course that opened in Ahmedabad last year. “Unlike Europe, where golf real estate was reliant on speculative investors and international buyers, in India, there is huge domestic demand from buyers looking to purchase second homes,” says golf legend Tony Jacklin. “This means that developers can build high-quality gated communities based on the real estate and membership business model.”

The main challenge for golf in India is acquiring large parcels of land since in many cases the tracts belong to multiple owners. The way around this is by clearing the misconception that you need a 400-acre, 18-hole championship course to play golf. Jack Nicklaus is on record stating, “We have people coming to us with 40 acres, 60 acres and 80 acres of land and an intent to do a golf course.” By using golf balls that travel different distances, developers can make far more efficient use of the space they have. Nicklaus wants the golf ball to fit the property and not the other way around.

Playing Host

Having played with golf legends who have hosted their own tournaments, Singh began planning an invitational in April 2012. It came to fruition in December in the form of the Shubhkamna Champions Tournament and by all accounts was a success. Singh’s presence as host as well as the apt timing of the event was enough to attract the 30 best Indian golfers (including Daniel Chopra, a Swede of Indian origin). Shiv Kapur won the tournament, but Singh believes Indian golf was the real victor.

He has even bigger plans for this year Singh is working on making the tournament a full field Asian Tour event, co-sanctioned by the Professional Golf Tour of India. He’s in talks with the Kensville Golf Course to have another such event there. Expanding a sport so alien to India will take time, but in Jeev Milkha Singh, we have an ambassador who will stay the course.

First Published: Feb 02, 2013, 07:10

Subscribe Now