The release of China’s version of a new map claiming Indian territories will only serve to exacerbate the military stand-offs involving thousands of soldiers on both sides of the frontier along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in the western Himalayas. On December 9, 2022, Chinese troops tried to transgress the LAC and dislodge an Indian post in the Yangtse area near Tawang sector. This led to clashes with Indian troops, leaving dozens with what the Indian army described as “minor injuries". The deployment of aerial platforms including drones by China in the region had preceded its attempts to unilaterally change the status quo in the Yangtse area.

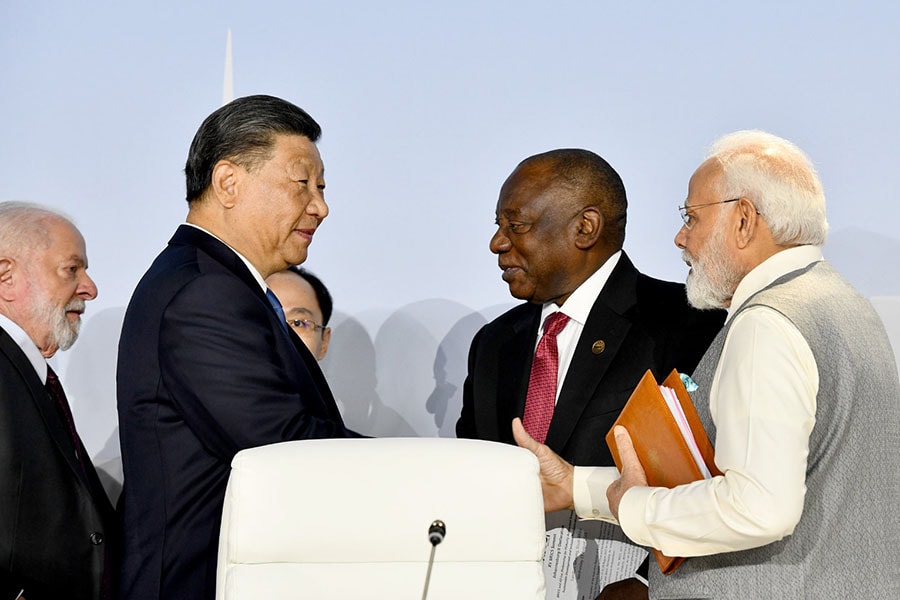

New Delhi’s protest over the map comes only days after Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi spoke with China"s President Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the 15th BRICS summit in Johannesburg last week. Modi is known to have highlighted concerns about the disputed Himalayan frontier and agreed on early disengagement and de-escalation of military tensions along the borders at Ladakh, according to reports.

The root cause of the fresh tensions is the McMahon Line, a poorly demarcated 885 km long-disputed boundary in the Northeast—a line that is continually shifted by rivers, lakes and snowcaps, one that runs from the eastern border of Bhutan along the crest of the Himalayas and passes the great bend in the Brahmaputra river emerging from the Tibetan plateau and flows into the Assam Valley.

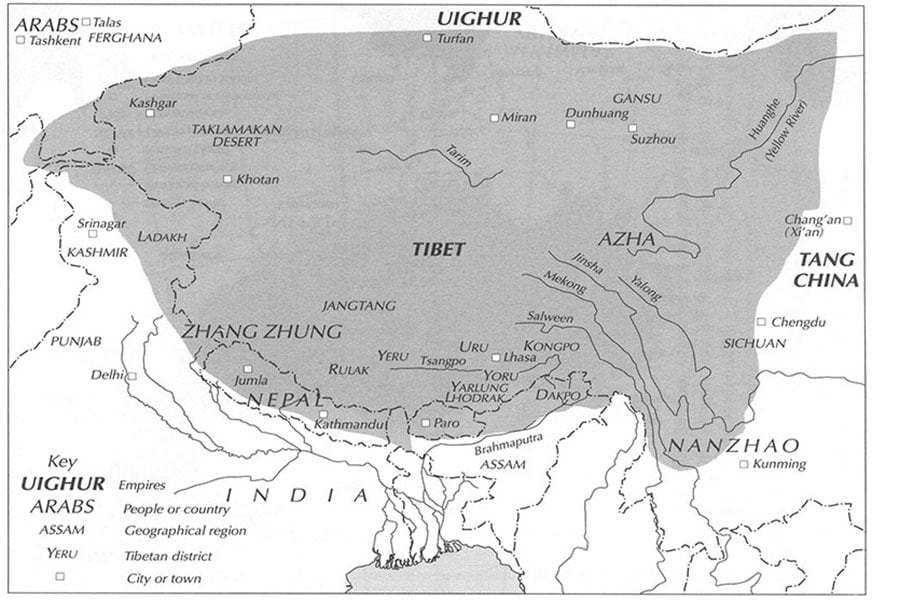

![]() Map of the Tibetan Empire (in grey), late 8th-early 9th century from Kapstein, Matthew. The Tibetans, Blackwell, 2006

Map of the Tibetan Empire (in grey), late 8th-early 9th century from Kapstein, Matthew. The Tibetans, Blackwell, 2006

The countries claiming a slice of the vast Tibetan Plateau—chiefly China and India—are aware of the might of a Tibetan Empire that once stretched over a territory far greater than its modern boundaries. Home to many diverse ethnic groups and pastoral nomads, the Tibetan kingdom was a significant power in Central Asia from the 7th to the 9th century. Three centuries later, the Tibetan Empire, troubled with conflicts on its borders—especially with the Chinese Tang Dynasty—and increasing religious strife from pro-Buddhist and pro-Bon factions, quickly disintegrated, its fragmented territories populated with an endless range of ethnicities and small kingdoms.

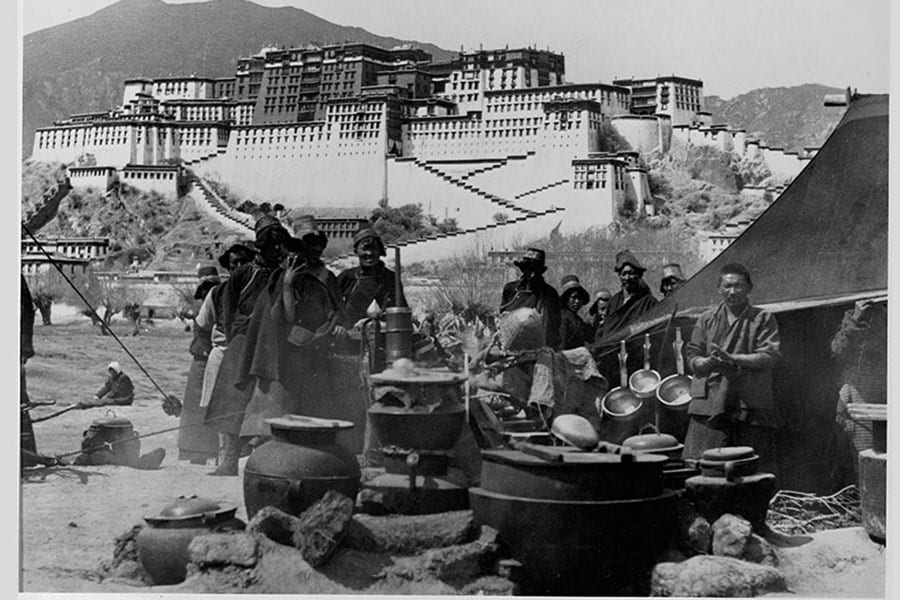

![]() Tibetans stand by a tent, with the Potala, the palace of the Dalai Lama, behind them circa 1901. Image: LOC/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

Tibetans stand by a tent, with the Potala, the palace of the Dalai Lama, behind them circa 1901. Image: LOC/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

The contemporary dispute over Tibet is rooted in religious and political disputes starting in the 13th century. China claims that Tibet has been an inalienable part of the country under the Mongol dynasty since the 13th century. Tibetan scholars counter that China was a region then, ruled by either the Mongol or Manchu empire. Scholars also say that Tibet was a protectorate, wherein Tibetans offered spiritual guidance to emperors in return for political protection. When the British, in an attempt to open relations with Tibet, conquered it in 1903-04, a Manchu-ruled China countered the British with attempts to increase control over Tibet’s administration. When the Manchu dynasty collapsed in 1912, Tibet declared independence and all Chinese officials and residents in Lhasa were expelled by the Tibetan government. Thereafter, Tibet functioned as an independent nation even while its international status remained unsettled.

![]() British, Tibetan and Chinese delegates at the Simla_Conference in 1913. Image: Alamy/Dinodia

British, Tibetan and Chinese delegates at the Simla_Conference in 1913. Image: Alamy/Dinodia

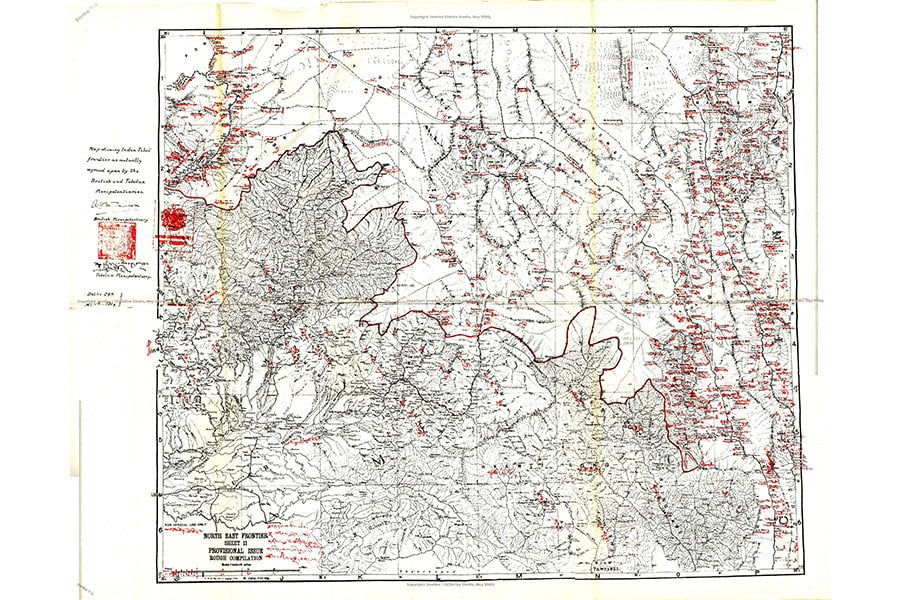

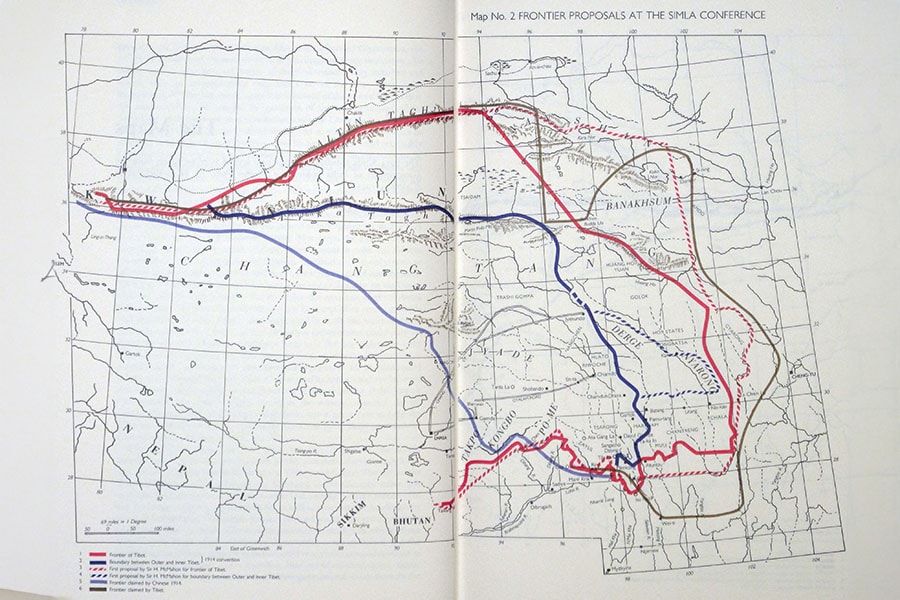

On 13 October 1913, the chief British negotiator Lt. Col Henry McMahon met with China’s representative Ivan Chen, and Tibetan PM Lonchen Shatra (sent by the Dalai Lama) in Simla to begin deliberations on two themes—(a) Tibet’s status (‘autonomy under limited authority of China’) and, (b) to draw the border limits of Tibet. The British, who were hosting the convention, wanted a defined boundary for Tibet, not just with India, but also with China. As the southern limits of Tibet flanking India’s northeast were an unsurveyed grey area, McMahon was awaiting survey reports from expeditions, admitting that he was “at a loss as to what really was Tibet".

![]() A map by British diplomat and Tibetologist Hugh Richardson. The light blue line represents the frontier claimed by China, while the dark grey line represents the frontier claimed by Tibet, and the bold blue line shows the boundary between outer and inner Tibet proposed at the 1914 Simla Convention.Image: Public Domain/Wiki

A map by British diplomat and Tibetologist Hugh Richardson. The light blue line represents the frontier claimed by China, while the dark grey line represents the frontier claimed by Tibet, and the bold blue line shows the boundary between outer and inner Tibet proposed at the 1914 Simla Convention.Image: Public Domain/Wiki

Over the next few months, McMahon proposed the division of Tibet into two zones—by drawing lines on a skeleton map to mark Inner Tibet (by a blue line) and Outer Tibet (by a red line), but China wasn’t accepting it. The meets dragged on for many months in Simla and Delhi. Finally, Ivan Chen proceeded to initial the draft and maps, only to inform McMahon later that his government had refused to accept—“repudiated"—his signing of the convention. Thus, McMahon and the Tibetan delegate agreed on an Indo-Tibet boundary on March 24-25 1914, while the Chinese delegate opted to stay out. McMahon drew a line in red ink on a small-scale map along the crest of the Himalayas which separated northeast India from Tibet.

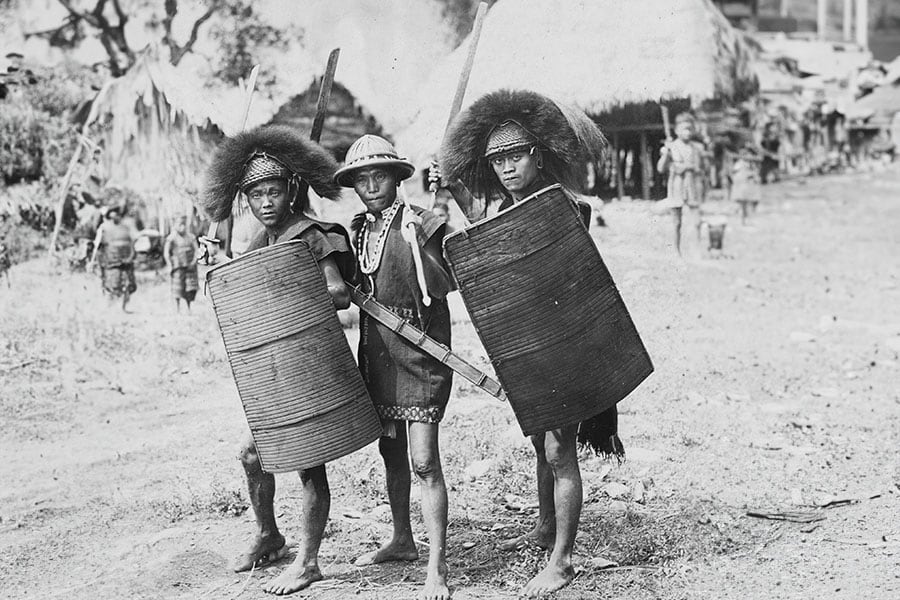

![]() Young tribes people in the North East Frontier Tract, circa 1930. Photo by Hulton-Deutsch/Corbis via Getty Images)

Young tribes people in the North East Frontier Tract, circa 1930. Photo by Hulton-Deutsch/Corbis via Getty Images)

From 1914 onwards, the British Indian government made agreements with the northeast indigenous peoples in the Himalayas to set up North East Frontier Tracts, bifurcating, amalgamating, and renaming areas over many decades until 1972, when the tracts together became a union territory and was named Arunachal Pradesh. On February 20, 1987, it was declared a full-fledged state of India. Culturally, largely Tibetan, Arunachal Pradesh is a savage territory for battle, with mountain passes as high as 15,000 feet still covered in snowdrifts as late as May, and thickly forested slopes lower down.

![]() Chen Yi, vice premier of China (saluting, second from right) visits Tibet to organise Tibet’s inclusion in the Communist Chinese framework. Reviewing local troops with Yi are the Dalai Lama, spiritual leader, and Panchen Lama, May 1956. Image: Bettmann/Getty

Chen Yi, vice premier of China (saluting, second from right) visits Tibet to organise Tibet’s inclusion in the Communist Chinese framework. Reviewing local troops with Yi are the Dalai Lama, spiritual leader, and Panchen Lama, May 1956. Image: Bettmann/Getty

After founding the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the new communist government in China sought reunification with Tibet and invaded it in 1950. A year later, the Dalai Lama’s representatives signed a seventeen-point agreement with Beijing, granting China sovereignty over Tibet for the first time. The agreement stated that the central authorities “will not alter the existing political system in Tibet" or “the established status, functions and powers of the Dalai Lama". The Chinese government points to this agreement to prove Tibet is part of Chinese territory while refusing to be bound by any treaties signed between Tibet and Britain, including the 1914 Simla convention where the British recognised Tibet as an autonomous area under the suzerainty of China.

![]() Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama (centre, on a white horse) escapes from Tibet to India, on February 1, 1959. Image: Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama (centre, on a white horse) escapes from Tibet to India, on February 1, 1959. Image: Universal Images Group via Getty Images

At the outset of the 1959 Tibetan uprising against the Chinese, fearing for his life, the Dalai Lama and his retinue fled Tibet with the help of CIA"s Special Activities Division, crossing into India on March 30, 1959, reaching Tezpur in Assam. It set the stage for a number of violent border skirmishes between India and China from 1959 to 1962, triggered by India"s granting asylum to the Dalai Lama.

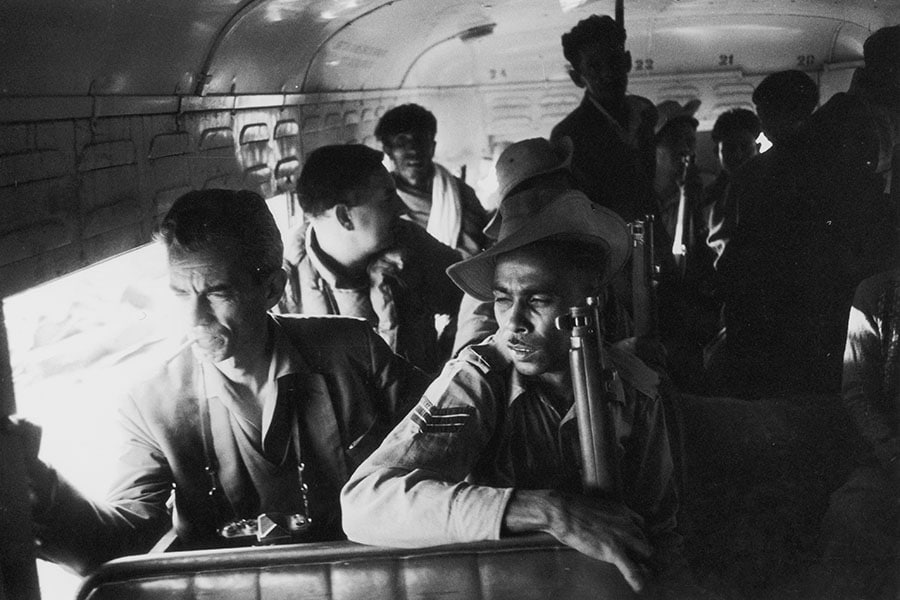

![]() Soldiers of the Assam Rifles arrive by train at Tezpur in India, during border clashes with China, circa November 1962. Image: Terry Fincher/Express/Getty Images

Soldiers of the Assam Rifles arrive by train at Tezpur in India, during border clashes with China, circa November 1962. Image: Terry Fincher/Express/Getty Images

The McMahon Line had become a point of contention. But India never expected China to attack, and when they did, on October 20, 1962, advancing on the western (Aksai Chin) and eastern sector(Arunachal), the outcome was humiliating for the Indian troops, outnumbered and killed by large battalions of war-ready Chinese troops who made inroads up to the outskirts of Tezpur in Assam. The attacks marked the beginning of the Sino-Indian War, which ended unexpectedly a month later when China declared a unilateral ceasefire and withdrew to its former positions behind the McMahon Line.

![]() This video frame grab taken from footage recorded in mid-June 2020 shows Chinese (foreground) and Indian soldiers during the incident where troops from both countries clashed in the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in the Galwan Valley, in the Karakoram Mountains in the Himalayas. Image: CCTV/AFP

This video frame grab taken from footage recorded in mid-June 2020 shows Chinese (foreground) and Indian soldiers during the incident where troops from both countries clashed in the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in the Galwan Valley, in the Karakoram Mountains in the Himalayas. Image: CCTV/AFP

The escalation of simmering tensions between the two armies is at an all-time high. Accusing India of crossing the border onto the Chinese side, a deadly 2020 clash with Chinese troops in the Galwan Valley near Aksai Chin, fought with sticks and clubs, not guns, left 20 Indian troops dead. On December 9, 2022, hundreds of Indian and Chinese forces clashed along LAC near Tawang, with both forces sustaining injuries.

![]() A tunnel under construction at the Sela pass in the Tawang, Arunachal Pradesh, April 2, 2023. Freshly laid roads, bridges, upgraded military camps, and new civilian infrastructure dot the winding high Himalayan route to the Indian frontier village of Zemithang. Image: Arun Sankar / AFP

A tunnel under construction at the Sela pass in the Tawang, Arunachal Pradesh, April 2, 2023. Freshly laid roads, bridges, upgraded military camps, and new civilian infrastructure dot the winding high Himalayan route to the Indian frontier village of Zemithang. Image: Arun Sankar / AFP

Unable to disengage across key areas of the disputed border, the two nations today are competing to build infrastructure along the LAC. India issued a gazette notification recently to begin work on the 2,000-km long Arunachal Frontier highway border highway, that follows the McMahon Line, to be built at the cost of Rs40,000 crore. The Border & Roads Organisation is presently constructing nine tunnels, including the 2.53-km long Sela tunnel, which will offer all-weather connectivity between Guwahati in Assam to Tawang in Arunachal, and will be the highest bi-lane tunnel in the world once completed. India has launched a $585 million "vibrant villages" scheme for civilians along the border.

China, meanwhile will soon begin construction on an ambitious new railway line connecting Xinjiang and Tibet that will run close to the Line of Actual Control (LAC) and through the disputed Aksai Chin region, according to a new railway plan released by the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) government. Beijing also announced its plans to upgrade two Tibetan towns—Milin and Cuona—on the border with Arunachal Pradesh to city status, linked by rail and airport.

![]() A view of the busy Qingdao Port handling containers headed for the Middle East, Africa, India, and Pakistan, in Shandong province, China, on August 30, 2023. Image: CFOTO/Future Publishing via Getty Images

A view of the busy Qingdao Port handling containers headed for the Middle East, Africa, India, and Pakistan, in Shandong province, China, on August 30, 2023. Image: CFOTO/Future Publishing via Getty Images

Despite frosty border relations, China is one of India"s biggest trading partners. India’s bilateral trade with China reached a record $135.98 billion in 2022, according to Chinese Customs data, driven by surging Indian imports of Chinese goods that were up by more than 21% last year. China"s exports to India climbed to $118.5 billion, a year-on-year increase of 21.7%. China’s imports from India dwindled to $17.48 billion, a year-on-year decline of 37.9. The trade deficit for India stood at $101.02 billion, crossing the 2021 figure of $69.38 billion.

Now, if only McMahon and the representatives at the 1914 Simla convention grappling with the drawing of border lines had thought long and hard about the saying ‘good fences make good neighbours’...

Sources: Council on Foreign Relations, Contested Lands: India, China and the Boundary Dispute by Maroof Raza/Westland, DW, BBC, China’s India War by Bertil Lintner/OUP