How the Apollo, Cooper Deal Was Botched

The $2.5 billion Apollo-Cooper marriage was called off before they could say 'I do'. Both parties are aggrieved, and everyone, it seems, is to blame. Together, they would have become the 7th largest t

Neeraj Kanwar was having a moment. On a holiday. In London. On December 30, 2013.

The 40-year-old managing director of the $2.4 billion Apollo Tyres, India’s largest tyre company, Kanwar had had a tumultuous year. Travelling for over 130 days, he had been holed up mostly in the US where Apollo Tyres was painstakingly trying to acquire Cooper Tire & Co. It was a year when he had spent most of his time explaining, negotiating and strategising escape routes out of one crisis to another when he was surrounded by people he didn’t quite trust, one of whom even took him to court and questioned his integrity in business. In a two-decade-long professional career, his integrity was the one thing he took immense pride in. When alone, it was also a year that often forced him to contemplate his next move, in business, in the courts.

But back in the comfort of his London home, surrounded by his two children and wife, during lunch, Kanwar was having a moment—of introspection, reflection. The year was finally coming to an end and he was glad. It was then that his mobile phone rang. The call was from a colleague in the US. “Hi, Neeraj. Cooper has called off the merger. Just announced,” he was told.

Kanwar didn’t react immediately. This was yet another ‘surprise’ in a year full of surprises. He got off the call quickly. Lunch had not yet been served. He got up to find a quiet corner. And called his dad.

Coming of age

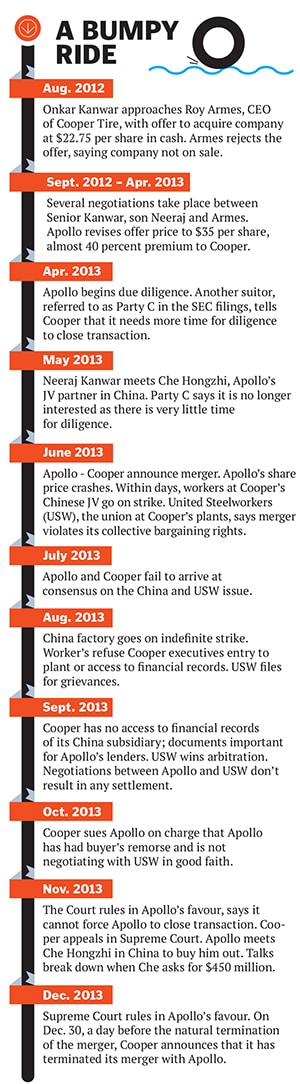

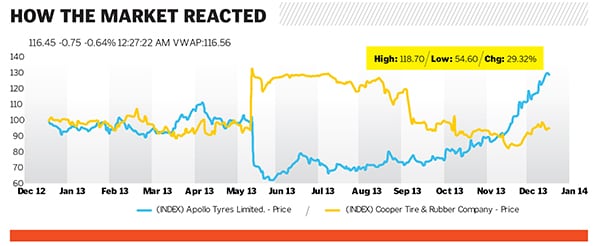

The Apollo-Cooper merger was announced on June 12, 2013. A day after the announcement, the price of the Apollo Tyres stock, which is traded on the National Stock Exchange of India and the Bombay Stock Exchange, dropped from the previous day’s close of Rs 92 to Rs 68.60 per share. A day later, it reached its 52-week low on concerns that Apollo was taking on too much debt to pay Cooper—nearly $2.5 billion.  The Apollo management had expected this reaction. In fact, they had anticipated that the stock would actually touch Rs 50.

The Apollo management had expected this reaction. In fact, they had anticipated that the stock would actually touch Rs 50.

That barrier was not breached but, still, Kanwar wanted to send out a message that he knew what he was getting into.

On June 14, a Friday, Apollo called a press conference at the Leela hotel in Chanakyapuri, New Delhi. Kanwar took centre stage, making a presentation, answering questions and always looking confident. His father Onkar Kanwar, 71, made a few statements and answered some questions but was happy to take the backseat. It was clear that the deal had also signalled a transition at Apollo.

The Cooper deal was Neeraj’s coming of age moment. The senior Kanwar said of his son, “Watch out for him. He also has the fire in the belly like I had in my younger days.”

Neeraj was convinced that the Apollo-Cooper merger would result in the perfect global tyre company. From a geographical perspective, Apollo was already big in India, Europe and Africa. Cooper was established in North America and China. In terms of products, Apollo had made inroads into getting contracts with car companies like Volkswagen and General Motors. Cooper had significant presence and experience in the replacement tyre market. Compared to their individual insignificant market position (Cooper at No. 11 and Apollo at No. 17), after the merger, the combined entity would become the seventh largest tyre company in the world.

It would be fair to say that the vision has been shaped by the father. In the 1980s, Onkar Kanwar got the chance to study Cooper Tire & Rubber Co, an American tyre major. Focussed on replacement tyres, Cooper was a hugely profitable company. Kanwar’s Apollo Tyres had a technical collaboration with General Tire International Co and on every visit to the US, the Indian businessman would hear about Cooper Tire. “They were making a lot of money. Coming back to India, I would tell my people to study this company,” Kanwar told reporters of the time when Apollo was still a fledgling company, having just escaped closure in the previous decade.

Analysts and journalists, though, were not convinced. So Neeraj tried to temper the mood, saying, “Only $450 million of the total $2.5 billion debt for the deal would be serviced by its India business. The remaining debt of $2.1 billion is a non-recourse debt, taken on cash flows of Cooper and Vredestein [the European subsidiary of Apollo Tyres].” It didn’t matter. The Apollo share price fell by another 5.6 percent that day. The Kanwars, however, were positive that the market would eventually realise the value in the deal. Father and son had already booked tickets to the US to close all the remaining formalities with Cooper. For them, it was a done deal. They couldn’t have been more wrong.

Sitting in a factory in Rongcheng, a city in the extreme north east of China, a 51-year-old Chinese man had been keenly following the events which unfolded after the announcement by Apollo and Cooper. And he was seething with anger.

Trouble in paradise

Neeraj flew into Beijing to meet Che Hongzhi on May 15, four weeks before the formal announcement of the merger.

Che, who is commonly referred to as Chairman Che, is the chairman of the Chengshan Group in China, which employs about 7,000 people in the city of Rongcheng. A former Communist Party member to boot, it would be fair to say that Che is a highly influential person. Cooper Tire has a joint venture with the Chengshan Group called Cooper Chengshan Tire Co, in which Cooper is the majority shareholder with a stake of 65 percent. Signed in 2006, this joint venture along with another facility (not part of this JV) contributes about 25 percent to Cooper’s global annual sales turnover.

In the course of due diligence, Neeraj wanted to meet Che to ensure both partners understood each other and, more importantly, that Che was comfortable about working together in the future. Except that the meeting turned out to be a disaster.

Che didn’t speak any English. Neeraj didn’t speak Chinese. Both had brought along translators. Since the meeting was set up by Cooper, two senior officials from the company were in attendance—Hal Miller, president of international business, and Allen Tsaur, vice president of Asia operations. Neeraj was accompanied by his legal advisor, a representative from Sullivan & Cromwell. Neeraj told Che about Apollo being in advanced talks to acquire Cooper, about how both companies are a great fit and how the China business is a critical part of the deal.

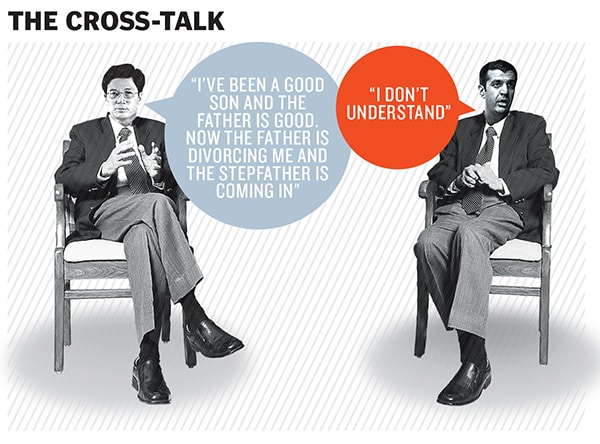

Che listened patiently but wasn’t pleased. “I’ve been a good son and the father is good. Now the father is divorcing me and the stepfather is coming in,” he said. Neeraj was baffled. He continued to outline the benefits of the merger but Che kept on repeating his issue with the “stepfather”. Che’s parting line: What was in this for him? If the merger was to go through, he would like to be compensated.

As revealing as this statement was, Neeraj tried not to make much of it. Meanwhile, none of these questions came up for discussion: Was Che comfortable with working with Apollo? If not, could the issues be ironed out? If he wanted an exit, how much was he expecting for his share? If Che were to exit, could Apollo run the subsidiary in China on its own?

Four weeks later, Neeraj went ahead and announced the merger anyway.

It wasn’t a wise thing to do. And little did Neeraj know that Che had plans of his own. On June 15, three days after the announcement, Che was in the US at the invitation of Cooper, with a bid of his own to acquire the company. He bid $38 per share, $3 more than Apollo had. Cooper had its own reasons to believe that Che’s financing sources were not as committed as Apollo’s. Despite the higher bid, it decided to go ahead with Apollo. Che left the US feeling insulted.

On June 18, a few days after Che’s sudden stunt in the US, the union at Cooper Chengshan Tire Company (CCT) sent an open letter to all Cooper employees criticising the merger. It said the acquisition was too highly leveraged and questioned Cooper’s ability to meet the needs of its workers and customers. This was the beginning of what would be a chain of events that would ultimately put the whole deal in jeopardy. On June 21, the 5,000-odd workers at the plant went on a strike. They got back to work a week later but stopped manufacturing any Cooper-branded tyres. Both Cooper and Apollo realised that the disruption in China needed immediate attention. Since neither had seen this coming, it was now an open question of who would bell the cat.

On July 1, Cooper and Apollo’s representatives met in the US to discuss a possible China strategy. Apollo stated upfront that this was Cooper’s problem. Neeraj was not going to meet Che again. Cooper must convince Che to agree to the merger. There could be no talk of compensation. He must be talked into coming on board. Roy Armes, the CEO of Cooper, along with his representatives, met Che in China on July 10. But the meeting was a non-starter. Che was disappointed and frustrated when he learned that Armes had turned up with nothing concrete to offer. Armes went back to the US empty handed.

A day later, CCT’s union sent a letter to Standard Chartered Bank, one of the bankers for Apollo, asking that it reconsider its decision to finance the transaction because of “significant reputational risks to your bank amid such a complex situation!” The next day, the union put out an advertisement in The Wall Street Journal questioning “who can guarantee the success of integration between Chinese culture and Indian culture?” The same day, the CCT union went on strike again. The plant was shut indefinitely. A few weeks later, Cooper’s managers were barred from entering the plant. They had no access to CCT’s financial books or records.

The father had lost control over the son. And that’s when the blame game began.

The Spat – Part I

However naïve this may seem, Apollo says that it took Cooper at face value that throughout diligence, Cooper maintained that it had excellent relations with its partner in China and there would be no problem. “Roy Armes and his whole team told us there will be no problem. Even if the guy is a little upset, we will manage it. We have a great relationship with him we’ve worked together for seven years,” says Sunam Sarkar, chief financial officer of Apollo Tyres.

Sarkar should know. He’s been part of the deal since day one. “To even conceive that the 65 percent shareholder of a company would not have access to his own plant and to his own financial records was, honestly, completely beyond conception,” he adds.

Cooper, on the other hand, alleges that Apollo knew that Che was expecting to be compensated. That should have been included in the offer price made for Cooper. And it wasn’t.

It gets worse. Even as all this was happening, Apollo had no clue that Che was one of the bidders in the race to acquire Cooper Tire. Subsequently, when Apollo did get to know (as late as October, but more on that later), the company alleges that this was one of the real reasons for Che’s anger. “Part of his anger was monetary and part of it was his face because he was asked to bid and he bid higher, but Cooper didn’t consider it,” says Sarkar.

Cooper denies any of this happened. “This meeting [on June 15 between the Cooper Chengshan Tire joint venture partner and Cooper executives] did not take place. No bid was received from Chengshan Group after the merger agreement was signed,” the company told Forbes India in an emailed statement.

But there is no debate on the fact that China was a critical part of the deal. And now it was in a limbo.

Experts believe that Apollo has no reason to feel cheated. Brian Quinn, a professor of law at Boston Law College, who has followed the case closely, says that under Federal law the directors of Cooper have an obligation to listen and evaluate any proposal that comes their way till the time they extinguish the rights of stockholders. “In the US these situations happen all the time. That might rub people the wrong way, but it is permitted under the law,” he told Forbes India.

To complicate matters further, time was of the essence. While entering into the deal, Cooper and Apollo had set themselves a deadline of December 31 to close the transaction. Debt financing was dependent on Cooper providing all the financial records by mid-November, with certain SAS 100-reviewed (that is, audited) records. With the China facility out of bounds, Cooper was worried. A question being asked around was, ‘are things slowing down?’

“What is strange is that this transaction had a very short fuse. Just six months,” says Quinn. “In normal domestic US transactions, people give themselves a year, even 18 months, for difficult deals. In this case it looks like the partners felt that either there are no issues or if there are, it doesn’t matter. We will get it done.”

Through June, July and August, Cooper and Apollo continued to talk to each other to try and solve the CCT issue. They couldn’t. That’s when another issue which had been simmering under the radar flared up.

On August 1, United Steelworkers (USW), the union representing employees at Cooper’s Findlay, Ohio, and Texarkana, Arkansas, plants, filed grievances, alleging that Cooper had violated its collective bargaining agreements by entering into the merger.

If the deal has to go through, Apollo must negotiate a new contract with the union. They had sat through a few meetings with Cooper and Apollo but nothing concrete had emerged. So they would go to court.

Forbes India reached out to David Jury of the United Steelworkers Union to answer a set of questions. On a call, he said, “I am the legal representative of USW with Cooper. Please don’t call me again.”

Trouble at home

Cooper Tire and USW don’t have a history of getting along well. During the economic downturn of 2008, when fuel prices shot up and US car sales came to a screeching halt, Cooper found itself in the middle of a crisis. To tide over the tough economic environment, it faced a tough decision to shut down one of its four plants in the country. That’s when 1,050 members of the USW union in Findlay, Ohio, agreed to give the company $30 million in concessions, in the form of pay cuts for new hires and reduced bonuses to keep the plant open. Subsequently, when the company’s fortunes improved, in October 2011, USW appealed to the management to increase wages. Cooper said that if the plant had to remain cost competitive, that was not possible. The workers were not happy. Starting late November 2012, the Findlay plant remained in lockout for three months.

In that context, USW first made its displeasure (about the merger) known to Cooper executives in a meeting on July 8, 2013.

Cooper explained to them the merits of the merger and tried to dissuade them from filing any grievance. On July 24, Sarkar along with other Apollo representatives travelled to Nashville, Tennessee, where the union has a regional head office, to meet with the USW. Sarkar says that it was a good meeting and he was surprised to see that USW had done its homework. “They spoke to our union leaders here in Kochi and they spoke to the works council in Europe to find out more about Apollo,” says Sarkar. “They told us in as many words that we have done our diligence on Apollo and we are very comfortable dealing with them. We are actually glad that a company like you is taking over.”

Nevertheless, the meeting didn’t result in any settlement. Like with Che in China, Apollo hadn’t come to the table with a compensation offer in mind. Instead, the company wanted to understand what it was getting into before committing to anything. On August 1, USW filed for grievances. Both Cooper and Apollo opposed the grievances and decided that any further negotiation between them and USW would take place only after arbitration, which they were sure of winning.

But five weeks later, on September 13, James Oldham, the arbitrator, ruled in favour of USW. The ruling said that Apollo must reach collective bargaining agreements with 2,500 USW locals at Cooper’s plants in Findlay, Ohio, and Texarkana, Arkansas, before it can proceed with its acquisition of Cooper. The deal was on hold. Cooper was anxious because time was running out. Apollo was surprised. All bets were off.

The Spat – Part II

Again as part of due diligence, in early 2013, a particular clause in the union legal agreement between Cooper and USW suggested that it was possible that post the merger announcement, the union might raise a red flag—they could have a say both in terms of fresh demands and a change of control in management. “There was a possibility assigned to it. When we raised it with the Cooper management, they said that in their view it didn’t apply at all and they were very confident that they would be able to settle with USW,” says Sarkar. If not, they were prepared to go for arbitration, which they were completely confident of winning, he adds, pointing out that no settlement value was factored in the $35 per share offer Apollo made for Cooper.

Cooper claims that during the extensive diligence, the company had informed Apollo of its historical, tumultuous relationship with USW and its likely reaction to the merger. Both parties had jointly agreed that first, it was unlikely that USW would go into arbitration and second, if it did then they would contest it. Both parties had agreed on the way forward. Relations between the two deteriorated further post arbitration.

The arbitrator ruled in favour of USW, and Onkar Kanwar, Neeraj and Sarkar quickly packed their bags for the US. The news reached them on a Saturday. On September 16, a Monday, both took a 2 am flight from New Delhi to New York. The next day they met with Cooper’s executives to discuss the negotiation strategy. That meeting didn’t go particularly well. Cooper claims that the first thing Apollo wanted to discuss was not the negotiating strategy with USW, but that the merger agreement would need to be re-negotiated considering the incremental costs which had come up—namely Che and USW. Apollo denies any such discussion took place at this point.On September 19, the sparring partners travelled to Nashville again to negotiate with USW. The union had ten demands, which included coverage of two other plants (not unionised) and one-time bonuses for all union members among several other conditions. By Apollo’s estimate, the additional cost of meeting those demands was about $130-140 million. Before the negotiations began, Apollo claims that Cooper’s estimate was just $10 million.

At the meeting, there were about 30 people representing USW and eight people from Apollo and Cooper. The union put forward their demands. The Apollo-Cooper party would then break out to consult among themselves the implications of those demands.

The proceedings continued the whole of Thursday and spilled over to Friday. By late evening on Friday (September 20), Cooper’s representatives started fretting. Stanley Weiner, partner at Jones Day, an expert in labour matters, and Cooper’s counsel, started pushing Neeraj to agree to the union’s demands, at any cost. “Their behaviour at that meeting was hugely dysfunctional because their lawyer aggressively was trying to get us to agree to whatever USW was asking for,” says Sarkar.

The company had scheduled a board meeting of its directors on September 30 to approve the merger. They wanted Apollo to settle with USW at any cost. Cooper felt that Apollo was not negotiating in good faith and was trying to delay closing the transaction.

Sarkar contends that Apollo was merely trying to find a way to work together, especially since the amount—$150 million—was not small change. “It is a question of affordability, long-term business sustainability, because whatever we agreed to would then go into union contracts which forever would have an implication on the company,” he says. “We hadn’t ruled out anything. We recruited an actuarial specialist to advise us. I think any prudent businessman would have done the same. You can’t commit to costs which you don’t fully understand.”

Negotiations between Apollo and USW continued the whole of the next week. Apollo though told Cooper to keep out of the discussions. Their impatience wasn’t helping. “At the end of the day, the arbitrator had given the responsibility to Apollo and USW to agree on a way forward,” says Sarkar. Even though there was no resolution on the USW front, on September 30, the Cooper board cleared the merger. On October 2, Apollo and Cooper executives met again in New York.

The meeting began with the latest update on the USW situation. Roy Armes, the CEO of Cooper, wasn’t happy that his executives weren’t allowed to be a part of the negotiations. Neeraj said that if Apollo had to settle with USW, it would cost the company an additional $150 million. That translates roughly into a $2.5-a-share downward revision of the $35 per share offer price (65 million Cooper shares outstanding). “We need to revise the price,” said Neeraj.

Armes was furious. “I am being asked to pay for something which I can’t even negotiate… I can go back to my board for a buck but 2.5 bucks is a lot,” Armes is believed to have said. And like many other meetings between these two partners, this one too ended in ambiguity. Armes’s parting line to Neeraj, according to Apollo sources, was: “You will see a lot of legality flying around because we have to protect our shareholder interest but I wouldn’t worry about that.”

Two days later, on October 4, Cooper sued Apollo in the Chancery Court of Delaware. The charge: Apollo had buyer’s remorse. It had breached the parties’ merger agreement by not using “reasonable best efforts” to close the transaction, but instead was trying to re-negotiate the deal price after labour unrest at various Cooper manufacturing facilities increased the likely cost of acquisition for Apollo. Cooper also sought an immediate implementation of the merger agreement, much before the closing date of December 31.

The legal suit was the final blow in this saga of distrust between the two partners. Once the matter was in the hands of lawyers, all communication between the two partners ceased.

Did Apollo see it coming? Sarkar says it was out of the blue. “Physically there was nothing more we could have done. Cooper didn’t have their financials in place and they knew that the banks needed the financials to be able to go to market. But they wanted to force this transaction,” he says. The trial lasted about a month. On November 8, the Chancery Court of Delaware, Judge Sam Glasscock III ruled that Apollo had not breached the terms of its $2.5 billion deal to buy Cooper Tire. The ruling also rejected Cooper’s buyer’s remorse claim and that Apollo was dragging its feet on closing the deal.

Sarkar says Cooper completely misread Apollo’s intentions. “It was the difference between the American professional mentality and the Indian promoter mentality. The American professional management thought, oh, Apollo’s share price has crashed by 40 percent so these people will have a rethink on the deal,” he says. “That’s not the case. Promoter management always looks at longer term strategic benefits. Unfortunately in our case, American professional managements, who are so quarter-to-quarter focussed, saw it purely as, ‘oh, these guys must be having buyer’s remorse’.”

Cooper still believed it had a strong case, so it filed an appeal to the Delaware Supreme Court. And strange as this may seem, Apollo still wanted Cooper.

The last rescue act

Rongcheng, located close to the Yellow Sea, doesn’t have an airport. The nearest is in a town called Weihai which is about a 45-minute drive away. The city is quite enterprising, though, and among the industries there is a large shipbuilding yard which is state-owned, an Arcelor steel coil plant and a few tyre companies.

On the night of November 11, three days after the court ruling, Onkar Kanwar, Neeraj and Sarkar left on a Singapore Airlines flight for Beijing. From Beijing they flew to Weihai. They got to Rongcheng at 11 AM on September 13. They checked into a government hotel, had lunch and began waiting anxiously for a special guest—Chairman Che. Che along with his translator, lawyer and two other company executives arrived at 2.30 pm. It was a fairly difficult start to the meeting, say Apollo representatives present there.

“You people have insulted me,” he began.

Senior Kanwar took charge. “Legally, Apollo was not even allowed to have any direct interface with you given the fact that Cooper is your shareholder. The transaction we are doing is only a change in shareholding at the American level,” he said. “And everything else below that remains exactly as it is. But if we have hurt you or insulted you in any way, I apologise on behalf of Cooper, on behalf of us.”By the end of the three-hour-long meeting, Che had mellowed down. He claimed that he had been taken for a ride by Cooper. A few years back, he had sold his 15 percent stake in the joint venture to Cooper and all he got was $18 million. The other pinprick was being rejected despite a higher bid than Apollo. Their meeting ended with Che inviting the Apollo team to come and visit his tyre plant the next day. On November 14, Apollo executives along with Che took a long tour of the factory.

Their next meeting was with the mayor of Rongcheng. It was followed by lunch and another meeting to discuss the way forward.

Che laid out the options on the table. A 65:35 status quo joint venture, where Apollo would own 65 percent was out of question. Option 1: Going forward, he would like to have a majority stake in the venture, from 35 to 70 percent. Option 2: Apollo should buy him out and run the plant themselves. Apollo liked Option 2. But Sarkar says that there was a huge difference in valuation expectations. “Our range was $142 to $200 million. He started at $500 million. We asked for a basis for that. But he said no, this is what my company is worth,” he says. After some deliberations, he came down to $450 million.

But that was it. Apollo left the negotiation table. It was not a price the company was willing to pay. “Finding a way doesn’t mean finding a way at any cost. It doesn’t mean we will give USW $150 million. It doesn’t mean we will give Chairman Che $400 million bucks. It has to be finding a sensible way forward,” says Sarkar.

On December 16, the Delaware Supreme Court dismissed Cooper’s appeal.

On December 18, Armes called Onkar Kanwar with a suggestion that both partners hold a conference call to discuss a post December 31 scenario. “Let’s find another way to do this,” he said. The group got on to the call. A suggestion for extending the December 31 deadline was immediately rejected since the very nature of the acquisition had changed. What they agreed on is that a small team be formed at the earliest to look at the contours of a new deal. A four-member team was decided on. From Apollo: Sunam Sarkar and Gaurav Kumar, group head, corporate strategy and finance. From Cooper: Brad Hughes, vice president and CFO, and Hal Miller, president, the International Tire business.

This small group didn’t have a single meeting post that call. The holiday season was upon them. On December 30, 7 am, Ohio time, Cooper announced that it had called off its merger with Apollo.

A few minutes later, Neeraj Kanwar, in London, got the call. He said he was surprised and disappointed by the news.

The moment for the deal had passed.

(Additional reporting by Prince Mathews Thomas)

This story has been constructed from court documents, Securities and Exchange Commission filings by Cooper Tire, conversations with Apollo Tyre executives and independent experts. Despite repeated attempts, Cooper refused to engage, saying they “will not have any additional comment at this time”.

First Published: Jan 31, 2014, 07:25

Subscribe Now