What's Cooking in the Prestige Kitchen?

How TTK Group's TT Jagannathan battled competition and product fatigue with constant innovation and consumer proximity

Seven years ago, while cooking in his kitchen, TT Jagannathan, the TTK Group boss, had wondered why people don’t use microwave ovens to cook rice. The answer was immediate and obvious—the process would make the rice dry. He took that thought to his office—a nondescript high-rise on Bangalore’s Brigade Road—and discussed it with the members of his research and development department. For the next five years, a team worked on designing a microwave pressure cooker that would yield the same results as a regular pressure cooker. In late 2011, it launched the product in Japan, which has a huge appetite for both rice and technology. It turned out to be a big hit. (It even got a patent in Japan for the product earlier this year.)

Aggressive marketing had worked. But there was a less obvious reason too: Fukushima. The nuclear disaster that hit the country earlier that year had created huge demand for energy efficient appliances—including microwave pressure cookers.

This was a case of disaster helping business. Jagannathan has experienced the other side of the coin too, when disasters can also be, well, disasters. Consider the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center. Around that time, TTK Prestige was selling its pressure cookers in the US under a brand name that was Indian, yet familiar to American customers—Manttra. This business, under the direct supervision of Jagannathan, was showing promise. But the tragic events of that day resulted in an economic slowdown that led to several bankruptcies, including that of 16 of the 27 partners that TTK had at the time. The company lost money and, eventually, decided to shut down the US business.

The scenario at home was no better. The unorganised sector was eating into Prestige’s market share. Excise duty and sales tax added up to over 50 percent, making branded products such as Prestige and Hawkins too costly. “And it is neither a rocket nor an iPhone. Anyone could make it, and they did,” Jagannathan says. One way out was to add features that the mass players couldn’t. He decided to launch a smart cooker with advanced aspects. That flopped in the market, not least because one of the parts was defective. The company had to recall those pieces. By 2002, its losses were half of its net worth, its debt was four times its equity, and it was in a segment that had stagnated.

This was especially painful for Jagannathan. Prestige is the flagship company of the TTK Group, founded by TT Krishnamachari in 1926 before he went on to serve as a finance minister in Jawaharlal Nehru’s Cabinet. In the 1970s, when almost every company in the group (which has interests in a variety of segments including pharmaceuticals and health care services) was losing money, Prestige held strong in fact, its cash reserves had helped fund the turnaround of others.

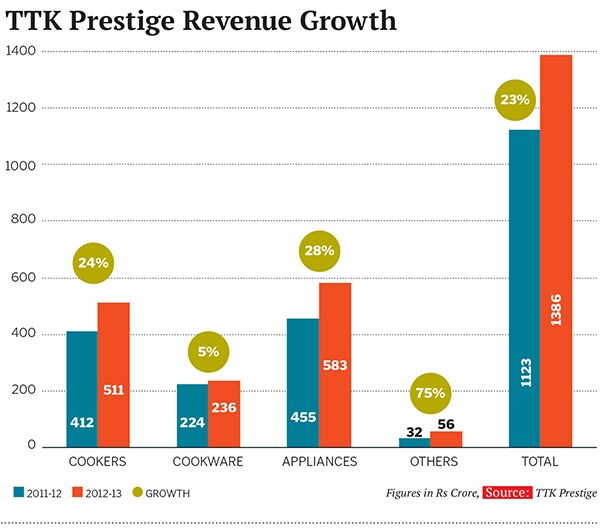

Cut to 2013 and Prestige has gone beyond pressure cookers. It now makes a range of kitchen appliances—from mixers to microwave ovens to iron boxes. It is a major player in retail too—it will have 500 outlets by the end of this year, and double the number in the next three years. And the picture only gets rosier. Its five-year growth rate is 33 percent against the sector’s growth of 12 percent. Its operating margin, at 13.6 percent, is above the sector average. And the markets have acknowledged the growth: In the last five years, its share price has gone up by 2,300 percent, earning higher slots in the Forbes India Rich List in the last two years. Jagannathan does not feature in the most recent list since the stock, after much yo-yoing, is just five percent over what it was during the same period last year. But that does not diminish the way Jagannathan has turned around TTK Prestige, quietly, without much fanfare. His path involved going back to basics, some unconventional thinking, using insights from the social sector, working with the government, and, above all, an unwavering focus on innovation.

Most media profiles of the 66-year-old Jagannathan focus on his love for cooking, the time he spends in the kitchen and how that helps him in product development (a role he took up in Prestige from day one, partly because of his training as an engineer at IIT, Madras). But Jagannathan is also an inveterate traveller who spends 15 days in a month on the move, mostly visiting dealers, spending the time in shops and talking to customers. He was just back from a trip to Kerala when he spoke to Forbes India, and he had met 79 dealers in those two weeks.

He prefers to get his own intelligence since, he says, surveys, can be made to tell you what you want to hear. The alternative is to develop one’s gut feel. In that he is not different from his father. He took big bets with very little information, just based on his instincts. But the results were mixed. TTK entered areas much before others. For instance, it made ball point pens even when it was not accepted in legal documents it got into condom manufacturing, a business that went on for several years without making money till the government introduced contraception programmes and became a big buyer. Worse, TTK didn’t have the money to sustain these initiatives till the markets developed. Jagannathan has learned from those experiences—and his own views are complemented and challenged by others. “We are like chatur muha brahmas [the Hindu deity Brahma, with four heads facing in different directions],” he says of his top team. “We all look in different directions, and don’t agree on everything.” For example, he was against inner lid pressure cookers and gave his go-ahead only half-heartedly. It turned out to be a good call.

He prefers to get his own intelligence since, he says, surveys, can be made to tell you what you want to hear. The alternative is to develop one’s gut feel. In that he is not different from his father. He took big bets with very little information, just based on his instincts. But the results were mixed. TTK entered areas much before others. For instance, it made ball point pens even when it was not accepted in legal documents it got into condom manufacturing, a business that went on for several years without making money till the government introduced contraception programmes and became a big buyer. Worse, TTK didn’t have the money to sustain these initiatives till the markets developed. Jagannathan has learned from those experiences—and his own views are complemented and challenged by others. “We are like chatur muha brahmas [the Hindu deity Brahma, with four heads facing in different directions],” he says of his top team. “We all look in different directions, and don’t agree on everything.” For example, he was against inner lid pressure cookers and gave his go-ahead only half-heartedly. It turned out to be a good call. But the one thing he does do? Listen to customers. When TTK was still suffering losses, he visited a free school that his family runs near Kumbakonam, Tamil Nadu. The village had a population of about 5,000 people, almost all of them farmers and, many, illiterate. About 3,500 children (including those from neighbouring villages) attended the school. He decided to step out and talk to the parents in their homes. He found that none of the households had a pressure cooker, and almost everyone had a mixer. This was a surprise to him because he had always assumed that a pressure cooker was the first purchase made after marriage. He asked around in other places and heard the same story everywhere. That is when he realised that you can cook without a pressure cooker, but you can’t grind without a mixer. And Prestige was only into pressure cookers.

But the one thing he does do? Listen to customers. When TTK was still suffering losses, he visited a free school that his family runs near Kumbakonam, Tamil Nadu. The village had a population of about 5,000 people, almost all of them farmers and, many, illiterate. About 3,500 children (including those from neighbouring villages) attended the school. He decided to step out and talk to the parents in their homes. He found that none of the households had a pressure cooker, and almost everyone had a mixer. This was a surprise to him because he had always assumed that a pressure cooker was the first purchase made after marriage. He asked around in other places and heard the same story everywhere. That is when he realised that you can cook without a pressure cooker, but you can’t grind without a mixer. And Prestige was only into pressure cookers.

Much of the path that Prestige took thereafter emerged from that insight. Jagannathan came back to Bangalore and called for a strategy session. It was held in a rundown hotel, and the executives arrived in a bus, not a car. (Jagannathan’s focus, when he took over the company at barely 25, mostly revolved around cost-cutting. The tightfistedness endures even today. He always flies economy, and insists on others following his example.) The next several hours were spent discussing the way forward. It became clear to them that the only sustainable path for Prestige was to expand to appliances—mixers, toasters, kettles and so on—even as they make their operations more efficient. The top management divided work among itself. For example, negotiating with the unions and the government went to K Shankaran, director, TTK Prestige. Jagannathan retained product development—only, the scope had become much wider.

More recently, at another get-together in Kovalam, Kerala, his top team worked on a statement that would guide the company through the next few years. It believes it came up with something simple yet powerful: A Prestige in Every Kitchen. It is powerful because Chandu Kalro, COO, Prestige, says it creates a much bigger market. “We have felt the pain of being a big fish in a small pond moving to a bigger market gives us a lot of freedom,” he says.

Even today, few relate TTK Prestige to the term unconventional. Its office on Brigade Road in Bangalore, nestled on the 11th floor of a high-rise, won’t pass muster as modern. The foyers in the offices of the top management resemble a retail shop—they are too busy to care about the aesthetics. “The fact is that a lot of things that we did were unconventional,” says Jagannathan. On top of that list would be the decision to get into retailing. This was not meant to be an additional revenue stream or a step to fill the gaps in the network. The move was prompted by the distributors’ lack of belief in the new products.

That made Jagannathan do what he does best. He went straight to the customers and tried to sell his wares to them. The results were encouraging. The first full-fledged Prestige Smart Kitchen opened in Coimbatore to a positive reception. “Then interesting things started happening. The traditional pathra kadais [utensil shops] never stocked appliances. Now, after seeing their customers step into a Prestige showroom, they wanted to stock our appliances too,” he says.

Not only did it generate credibility, it got Prestige closer to the customer too. “Owning retail stores is just one element of a multi-distribution approach that any consumer product company in India has. It allows companies to move closer to the consumer, understand market needs and get better realisation,” says Ankur Bisen, a vice president at Technopak Advisors.

More recently, even as there are signs that the economy will weaken, TTK Prestige has stepped up investment to increase its production capacity and expand its retail network. It has also signed on Bollywood actors Abhishek Bachchan and Aishwarya Rai Bachchan to promote the brand.

Critics point out that these steps don’t always work. An executive from a competitor said Prestige made a serious attempt at getting into modular kitchens, which continues to be a growth segment. “But they never got that right. The customers were unhappy and they burnt their fingers,” he says. Similarly, post the turnaround, the company made a big deal about selling its wares through unconventional channels such as NGOs. It seemed to be a great idea on paper however, it never quite worked out.

But you win some and you lose some. That’s how it works in business.

Jagannathan was never interested in running a business. He was on his way to get his PhD from Cornell he had already landed a job at thinktank Rand Corporation and wanted to settle down in the US for good. When his parents asked him to come back, he requested them to move Westward instead. “My father didn’t agree, because the group had taken money from depositors. If he had to file for bankruptcy… that would mean betraying them. He insisted that I come back, and turn it around,” says Jagannathan. Part of the reason why he had to return was that his elder brother was an alcoholic. He died when he was still young. (As a result, his widow took up alcohol rehabilitation as a social cause, got herself formally trained and set up a hospital. TTK Hospital is considered to be the best in its field in South India.)

If it is a family business, it is not just business, says K Venkat Subramanyam, an investment banker who has worked with business families in the south.

“What you do always extends beyond your business—you deal with the government, you deal with society,” he says. (Remember that Jagannathan’s big insight that mixers have a bigger market than cookers had hit him when he was doing the rounds in a free school.)

So, even as it was fighting fires—it also had to deal with a long-drawn labour negotiation—TTK took it upon itself to lobby the government to bring down the excise duty in 2002. Shankaran made frequent trips to New Delhi to make a case for the organised sector.

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was in power then, with Atal Behari Vajpayee as the prime minister. Shankaran not only collected reams of data to show how the high duty was hurting the company, he also quoted an eloquent parliamentarian who was against the imposition of excise duty when it first came up for discussion: Vajpayee himself.

The government soon rationalised the excise duty.

While the external shocks (and cushions) can change the dynamics of a business, its success boils down to good execution—and a practical approach to innovation. “A product innovation platform is the most important growth driver. Such innovations will surely help Prestige capture the imagination of an evolving India and will keep Prestige's growth potential intact,” says Bisen of Technopak. “It is not so important to judge the performance of every innovation outcome. Some may succeed and some may not. The process and the approach to innovation is important and, in that sense, Prestige is a good example.”

Nothing highlights this as much as the time Jagannathan himself spends on these two activities—and the fact that 80 percent of its revenues (see TTK Prestige Revenue Growth) come from the products they had introduced in the last three years. He spends 15 days a month visiting his customers and dealers and two days a week on product development. He gets some of his ideas from working in a kitchen, and passes them on to his team.

A few years ago, while trying to knead flour for roti, he felt there might be a market for a convenient kneader. While these were available for Rs 5,000, they were separate devices and occupied additional space in the kitchen. His idea: Why not bring it out as an attachment for the mixer? It turned out to be a huge success.

Similarly, the microwave pressure cooker, which grew out of his ruminations in the kitchen and became a big hit in Japan, is doing well in the US too. There, Prestige has a tie-up with QVC and it is picking up steam. The first tranche of 80,000 pieces got sold in 10 days. TTK is in the process of sending the second tranche of 14,000 pieces.

But its reception in India was instructive. The microwave cooker was a flop. The lesson was learnt. “People don’t want to cook in plastic here,” Jagannathan says.

Lessons like these keep him on his toes. “Look, what we are doing is not rocket science. What we do today, anyone can do tomorrow. The only way to keep growing is to keep innovating,” he says.

In the last five years, TTK could gain market share over Hawkins because there wasn’t much product innovation from the latter especially in induction-friendly and stainless steel pressure cookers and cookware. But that is set to change even as Hawkins is stepping on the gas.

And, in the appliances segment, TTK has to compete with foreign players.

With the economy slowing down, it also has to contend with unbranded producers/cheaper brands since wallets tend to overpower the lure of brands in customer decisions in an uncertain environment.

For growth, then, constant innovation might be necessary, but not sufficient. That is yet another challenge for the battle-inured Jagannathan.

First Published: Nov 28, 2013, 06:36

Subscribe Now