Can e-cigarettes survive the war against vaping?

E-cigarettes were supposed to save lives and revitalise the smoking industry. But anti-smoking zealots, government regulators and Big Tobacco seem determined to snuff out the market—and any entreprene

In the winter of 2008, Jan Verleur was living on the outskirts of Prague, working on a novel about three failed internet entrepreneurs who invest their dwindling capital in an ecstasy-smuggling ring. It wasn’t autobiographical, but Verleur, 36, was writing from experience with failed ventures. His most recent had been an ambitious pornography business that lost $22 million of investors’ money, including $1.6 million of his own.

One day, as he was picking up a pack of smokes at a Vietnamese convenience store, he noticed a box of e-cigarettes. He tried one, and it leaked liquid into his mouth. “The technology wasn’t ready for market,” he says, “but the idea struck me as amazing.” Soon after, Dan Recio, his buddy and colleague in the porn business, persuaded him to return to the US and take another crack at making money by satisfying a different human craving.

The nascent e-cig market was wide open. Startup costs were low, and regulation was non-existent. The potential payoff looked huge: Vaping seemed poised to grow into an enormous global market for a healthier product. Invented in 2003 by a Chinese pharmacist whose father had died of lung cancer, e-cigarettes use lithium-ion batteries to heat nicotine-laced liquid, turning it into a vapour that has only traces of some of the 60-plus carcinogens in cigarette smoke. At first, Verleur and Recio’s Miami-based company, VMR, looked to be riding a big, beautiful wave.

But the industry has shifted dramatically in the six years since Verleur and thousands of other entrepreneurs jumped in. Demand for e-cigs has turned out to be smaller than at first expected. It grew from virtually nothing a decade ago to an estimated $3.7 billion in the US last year, according to ECigIntelligence, a British outfit that supplies information to the industry. But Nielsen reports that sales in convenience stores and big retailers like Wal-Mart have started to contract, shrinking 6.2 percent in the 52 weeks that ended on March 26. Nielsen doesn’t capture sales online or in America’s 10,000 vape shops, but last year, those channels were flat for VMR, which logged 2015 revenue of $50 million. All told, e-cig sales still pale in comparison with the $92 billion US cigarette market.

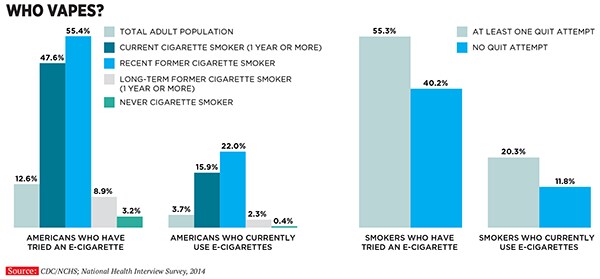

Many smokers try e-cigs once and abandon them, disappointed that vapour doesn’t taste or feel the same as real smoke, and gives a slower nicotine hit. “There is a lot of trial and a lot of rejection,” says tobacco analyst Vivien Azer, of Cowen and Company, in New York. “I’m not convinced the e-cigarette market will grow at all.”

Meanwhile, the forces arrayed against the many little players trying to grab a piece of that smaller-than-expected pie are daunting. Vaping entrepreneurs are up against a three-headed monster—Big Tobacco, the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) and an army of anti-smoking zealots—which is able and more than willing to wipe them out.

Tobacco giants like Reynolds and Altria have leveraged their fat balance sheets, huge sales forces and established distribution channels to enter the e-cig market and now own the top four brands in the US. Vaping cognoscenti say those are inferior devices that don’t really threaten Big Tobacco’s core product, traditional cigarettes (the tobacco companies insist they are committed to their cigarette alternatives).

More ominous for smaller players like Verleur: The FDA is expected to announce regulations soon that will treat e-cigs as tobacco products. If a draft rule released by the FDA in 2014 stands, thousands of e-cig products on the market will have to go through an onerous pre-approval process that e-cig companies say could cost them as much as $2 million per item. (The FDA puts the figure at $330,000.) VMR, which sells mostly online, offers more than 500 types of e-liquids, vaporisers and e-cig accessories, so fully complying with the new regulations will cost it anywhere from $175 million to $1 billion. Daniel Walsh, CEO of Purebacco, an e-liquid maker in Gaylord, Michigan, which sells more than 200 selections, calls the impending rules “Vapocalypse”.

The FDA has been egged on by anti-smoking groups like the American Lung Association and the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, which have taken a hard line against vaping. Ignoring or minimising the fact that millions of smokers have used e-cigs to quit or cut down, the anti-smoking lobby instead obsesses over the minimal health risks of vaping. They prefer that would-be quitters stick with patches and gum, which work as little as 7 percent of the time. Some 70 percent of American smokers say they want to quit, and 480,000 people died last year of smoking-related illness.In an emailed statement, FDA spokesman Michael Felberbaum says, “The FDA’s responsibility is to protect Americans from tobacco-related disease and death,” insisting that the agency’s objective is to learn as much as it can about e-cigs before approving them rather than put anyone out of business. Yet the proposed rules require that companies present research findings on the impact of every product on the population and gauge the likelihood that ex-smokers will start vaping, a near-impossible task for small players like VMR.

Joel Nitzkin, former co-chair of the Tobacco Control Task Force of the American Association of Public Health Physicians, who is now a fellow at a free-market think tank called R Street Institute, says of the FDA, “They think they’re on a mission from god. The horrific part is that they’re going to maintain cigarettes as the lead nicotine-delivery product in American society.” What’s more, he says, “they are refusing either to tell the public or allow manufacturers and vendors to tell the public about the difference in risks between e-cigarettes and tobacco cigarettes.” Indeed, even if a vaping company can jump through the FDA’s proposed regulatory hoops, it won’t be allowed to claim its products pose less harm than traditional cigarettes.No one suggests that e-cigs are completely safe. They deliver nicotine, which can interfere with brain development in young people, harm a developing foetus and pose risks to people with cardiovascular disease. E-cig vapour contains a dozen or so of the carcinogens found in cigarette smoke, though at very low levels. As an August 2015 report from Public Health England, an arm of the UK’s health service, reported last year, e-cigs are 95 percent safer than cigarettes. This April, the Royal College of Physicians cited that figure and urged smokers to switch to vaping.

But the British evidence hasn’t swayed anti-smoking advocates like the American Lung Association’s assistant vice president of national advocacy, Erika Sward. “Cigarettes are the nuclear option,” she says. “That doesn’t make conventional warfare any less deadly.”

Media reports have fed the idea that e-cigs pose all sorts of dangers. In January 2015, the New England Journal of Medicine published a study that showed toxic levels of formaldehyde could be produced by a high-powered vaporiser. The report also noted that no one would ever heat e-liquid to that temperature. Likewise, when a Harvard study showed the presence of the chemical diacetyl in 75 percent of e-liquids, there were headlines about e-cigs causing irreversible scarring of the lungs, despite the fact that diacetyl is present in extremely low doses. The toxic chemical is hundreds of times more plentiful in traditional cigarettes.

Since Verleur started VMR, the American e-cig market has stratified into two broad segments: “Cigalikes,” which mimic traditional cigarettes, and “mods,” which are more powerful and satisfying.

Cigalikes, which include VUSE (Reynolds), MarkTen (Altria), blu (Imperial Tobacco) and Logic (JTI), are the Budweisers and Millers of the vapour market, sold in convenience stores and chain retailers. They are packaged to look like cigarettes, with a long, tubular battery making up the body, a cartridge of fluid where the filter would go and, on the tip, an LED that glows when in use. A VUSE startup kit costs $10 for a vaporiser, a battery charger and a cartridge of liquid that roughly equals a pack of cigarettes. Replacement cartridges are $6 for a pack of two.

Mods are more like craft brews. There are thousands of them, and they’re typically modified to accommodate more powerful batteries, for a greater volume of vapour and a more satisfying experience. Mods are open systems, meaning that the vaper buys bottles of nicotine liquid and fills the tank herself. Most are made by mom-and-pop entrepreneurs and small companies like VMR. They sell mainly in vape shops, which stock e-liquids that cost as little as $1.20 for the equivalent of a pack of cigarettes.

Big Tobacco brands have light-years to travel before their e-cigs make anywhere near the money combustibles do. Extrapolating from Nielsen-tracked retail sales numbers, the four top brands combined were responsible for just $300 million in US revenue last year, barely a rounding error in an industry where, in the same period, Reynolds alone brought in nearly $11 billion. Also e-cigs yield little if any profit. VUSE, the No 1 brand, which Reynolds introduced in 2014, was still in the red at the end of last year. Among the reasons for the poor performance, says tobacco analyst Vivien Azer: E-cigs’ relatively high manufacturing cost and heavy discounting to attract customers. By contrast, gross margins on Reynolds’s traditional tobacco products were 44 percent last year, according to Azer. (Reynolds declines to comment except to say that it is continuing to invest in VUSE.)

At VMR, Verleur has pushed to attract both the masses and the connoisseurs, offering cigalikes, mods and multiple e-liquids in convenience stores, online and in vape shops. A quarter of his business is overseas, where he sells in 30 countries. In December, he sold a 51 percent stake to a Chinese company, Huabao, in exchange for entrée to a largely untapped market, where some 315 million smokers spend more than $200 billion a year on cigarettes. Controlled by billionaire Chu Lam Yiu, Huabao had $558 million in revenue last year. The company supplies tobacco flavouring to the state cigarette monopoly and already sells e-cigs to the Chinese market. Huabao paid $23 million and left Verleur in control as chairman and CEO. (The deal includes a golden parachute that he says will pay him more than $23 million should he be ousted.) The three-headed monster has hounded him into business exile.

These days, Verleur shuttles back and forth between China and Florida. He lives half the year in a hotel in Shenzhen, where VMR has 60 full-time employees and contracts with 3,000 workers in two factories. The rest of the time he’s in Miami, where he says he’s “homeless” after splitting up with the mother of his third child. (“I’m a hard person to have a relationship with.”)

Before he hit on e-cigs, Verleur displayed a knack for sales and hit-or-miss entrepreneurship. As a freshman at Penn State, he says, he made as much as $30,000 a month selling $1,000 Cutco knife sets before dropping out. Next he got a job in Orlando with a company that sold web-design services. Then he followed a Cuban girlfriend to Miami, where he started and shut down a series of businesses, including one that sold sales-intelligence software and another that supplied Indian tech workers to American companies. “There were times when I’d have a million-dollar year,” he says, “and other times I’d lose a couple hundred grand.”

Or more. In 2003, he tried to build an online venture he hoped would become “the HBO of porn.” It produced its own internet programming, including a reality show called The Brothel, at studios in Miami and Prague. He planned to sell sex toys and lingerie on the shows and to pipe live porn into hotel rooms. “If I had endless capital, I think we’d be the largest adult entertainment company in the world today.”

When he got around to e-cigs, in 2010, he figured he’d be most successful online. Recio and he invested $7,500 each, as did a third partner. Within a year, VMR had moved into a ten-storey glass-and-steel office building in Miami, and revenue hit $19 million. Two years later, revenue ballooned to $75 million and the head count was at 180, split among Miami, Shenzhen, a distribution centre in Prague and small offices in Hamburg, London, Moscow and Hong Kong. Then came two years of declining sales and growing concerns about regulation.

By 2013, there were rumblings that online sales of e-cigs might be banned in the US. Verleur responded by selling a limited number of products in brick-and-mortar stores, despite much lower margins. Meanwhile, competitors, including NJoy, which had attracted investors like billionaires Sean Parker and Peter Thiel, were growing fast. Last December, anxious to strengthen his position before the FDA made its long-awaited move on regs, Verleur sold half of VMR to Huabao.

Verleur says he’s hopeful that the FDA’s regs will ultimately be softened. He’s sure, though, that it will soon be prohibitively expensive for VMR and other small players to introduce new, better products. “Big Tobacco wants to stop innovation in its tracks and make sure no one comes out with something that will collapse its empire,” he says.

Verleur himself remains a slave to the empire. Vaping has helped him cut down his two-pack-a-day habit. But he still smokes. “I have four or five a day,” he says. His brand? “Marlboro, my arch-nemesis.”

First Published: Jun 21, 2016, 08:03

Subscribe Now