A train chugs along the tracks. A man seated inside one of its compartments engages in a one-sided, animated conversation with a subject that’s not immediately visible. He talks about the book he’s reading, discusses his family and even suggests board games that they could play together. As the journey draws to a close, it turns out the man’s been talking to a bucket this whole time. A narrator’s voice kicks in: “Kuchh log balti hote hain yaar, aur balti nahin bolti. Bolta hai India, Ibibo.com par (some people are buckets and buckets don’t speak. But India does, on Ibibo.com).”

It was 2008, and this commercial was a regular fixture on Indian television. But behind the absurdly amusing advertisement, part of an expensive publicity campaign by Ibibo.com, lay an uncomfortable realisation.

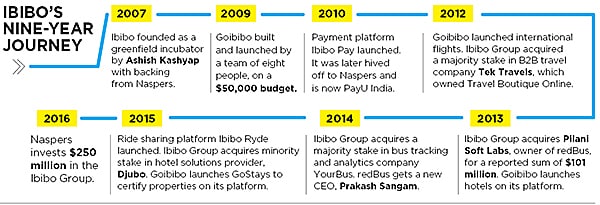

Founded in 2007 by former Google India head Ashish Kashyap, Ibibo began as a greenfield (incubator) operation in Gurgaon with financial backing from South African internet and media giant Naspers. A number of ventures would emerge from it, including an online gaming platform and a payment solutions provider.

In 2008, though, the most significant of these was a social media platform. It had, however, become increasingly clear to Kashyap and his team that a social media company, with the emergence of Facebook and existing competition, would struggle to find takers. Besides, digital ad revenues in India, on which such a service would depend, weren’t high enough. It was time to look for alternatives.

Soon after, in 2009, a team of eight people began work on an online travel platform, in a manner typical of Kashyap’s approach to organisation building: Create separate self-sufficient units and put constraints (they were provided with an initial sum of $50,000) on them to optimise performance. “The core idea was to put together an entrepreneurial, high-energy team and allow it to create,” says Kashyap who is the group CEO. The result was an online travel portal called Goibibo.com.

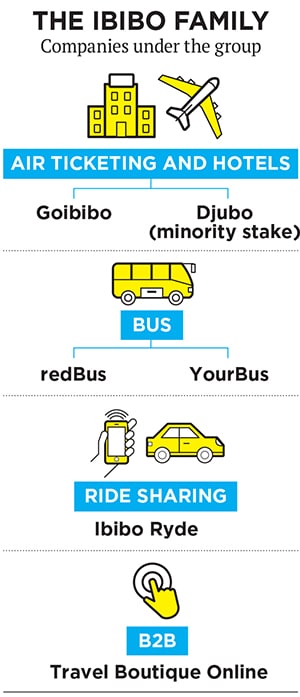

It has been seven years since, and Kashyap, 43, seated in a boardroom at the Ibibo Group headquarters for our meeting, has the look of a man in control. Reason: Despite being a late entrant into the online travel industry, the Ibibo Group, with its two major entities, Goibibo and online bus reservation platform redBus, has evolved into one of the largest players in the Indian online travel market. Its employee strength has grown from around 60 just two years ago to about 1,600. The number of hotels on its platform doubled over the past year to 43,000. Its topline more than doubled from Rs 114 crore in FY2014 to Rs 243 crore in FY2015 (though losses widened from Rs 117 crore to Rs 377 crore), according to the company’s latest filings with the Registrar of Companies. (The revenue numbers do not include revenues from redBus and business-to-business travel portal Travel Boutique Online.)

Now, Kashyap finds himself at perhaps the most important juncture in his decade-long entrepreneurial journey. Earlier this year, in a display of confidence in the Indian online travel market, parent Naspers announced it will be investing $250 million (around Rs 1,678 crore) in the Ibibo Group. The move is particularly significant considering that it follows Chinese travel giant Ctrip’s $180 million investment into MakeMyTrip in January 2016. To add to the already high stakes, the coveted hotels segment has now seen Goibibo emerge as the largest challenger to MakeMyTrip’s hegemony.

Between October and December 2015, Goibibo had the highest volume share of hotel bookings among Indian online travel agencies (OTAs) according to a Morgan Stanley research report released earlier this year. Another report by British research firm Millward Brown reportedly put it at second spot with an 18.9 percent market share, against MakeMyTrip’s 25 percent. Going by even the more modest of the two estimates, the company has come a long way. Consider that in 2009, when most of its competitors including Yatra.com, Cleartrip and MakeMyTrip were already present in the Indian market, Goibibo was an eight-person project.

Ask Kashyap whether he found this intimidating when starting out, and he just shrugs, saying, “The way I looked at it, online travel was a sector which was significantly broken, perhaps even more broken than product commerce.”

He then launches into a point-by-point critique of what he saw as fundamental problems with OTAs. While the user interfaces were attractive, the workflow of these websites was flawed. This would lead to frequent booking errors. After a cancellation, customers would have to wait upwards of a month to receive their refund. “The basic problem of trust, fulfillment and reliability hadn’t been solved,” he says.

There was also, he believed, a fundamental problem with existing business models. “Ecommerce is a low-margin business, which means that you have to have low, fixed-cost structures,” he says. That was why he found it surprising that most OTAs had physical retail outlets. Franchisee outlets and a large work force seemed to him to be the antithesis of what an online company should be doing. And so, having set out to address these apparent gaps, Goibibo was “quietly” launched in 2009.

Unlike many new-age internet entrepreneurs, Kashyap refrains from delving into origin stories and anecdotes. There are no elaborate tales about his struggles. He’d rather talk about the mechanics of building an operation and the all-important “problem” that needs solving. But to get it out of the way, he rattles out his resume with practised ease. Born and brought up in Delhi, Kashyap graduated in economics from the University of Delhi and later attended Insead, France. Before founding Ibibo, he headed Google India for a year and a half and prior to that he ran the ecommerce business for Indiatimes.com. “It was driven by a problem,” he says of his zeal to get Indian travel online. Through the course of our conversation, the problem-opportunity-solution triad appears frequently.

The other important theme that emerges is just as straightforward: Iteration. Over the years, travel was not the only market that Ibibo attempted a foray into. For a company that began as a greenfield project, experimentation came naturally. Inevitably, not all of the attempts were successful.

Ibibo Games, which created the popular online game Teen Patti, no longer exists. Its payments platform, Ibibo Pay (which later became PayU India), was sold back to Naspers, of which Ibibo Group is now a subsidiary. And then there was the ill-fated social media platform, Ibibo.com.

The company also acquired the online auto classifieds startup Gaadi.com in 2011 for $2 million. It was sold to CarDekho three years later for $11 million. Ecommerce firm Tradus, which unlike the others was not built by the team from scratch but was simply run by the Ibibo Group, shut operations in 2015. The latter was part of Naspers’s larger bet on Indian ecommerce, which also includes investments in Flipkart.

While the company’s early failures may have raised some concerns, “Ibibo and Naspers have done better than Rocket Internet and potentially even Tiger Global and SoftBank in India,” says Kashyap Deorah, serial investor, entrepreneur and author of the book The Golden Tap: The Inside Story of Hyper-funded Indian Startups.

For instance, he says, Naspers is conspicuous by its absence in the food tech space where many others have burnt their fingers. As for Ibibo, “there were times of exuberance, with them saying ‘don’t be a balti’, and trying to create a social network. But they learned their lesson early and stuck to their guns.”

There was evidence of this even in Goibibo’s early years. “We did not bite the cake in one go,” says Sanjay Bhasin, co-founder and CEO, Goibibo. Instead of spreading itself thin across several verticals, Goibibo went one step at a time. Till 2012, the company only sold domestic air tickets and worked on basics—improving the speed at which the transactions took place and minimising the number of clicks it took to book a ticket, among other things. In 2011, it also introduced instant refunds, which, according to Bhasin, was a first among Indian OTAs. The following year, the company launched international flights on its platform and acquired Travel Boutique Online. Even then, the company was still very much on the sidelines of online travel in India. But that was set to change.

Goibibo began selling bus tickets on its platform in 2012, the same year that it launched international flights. By then, Phanindra Sama, Charan Padmaraju and Sudhakar Pasupunuri, three friends from Birla Institute of Technology and Science, Pilani, had already built redBus into India’s largest bus reservation platform.

Not surprisingly, when Goibibo made a foray into bus reservation, Kashyap proposed they partner with redBus. The partnership set the stage for what would be one of the biggest deals in the Indian startup ecosystem at the time. “The traction on Goibibo for bus ticketing with strong unit economics and the fact that redBus was a market leader, attracted us to fully acquire it,” explains Kashyap. redBus was acquired for a reported figure of $101 million in 2013. “It was in line with Naspers’s theme of betting on travel in India,” says Deorah. “It looked like India travelled a lot by bus and here were guys who had created a back-end platform for bus inventory.” It seemed like a cinch. But the move took many by surprise.

As the euphoria around the deal began to subside, reports emerged that senior executives in redBus were unaware of the impending sale and many of them left the company after differences over the awarding of employee stock options (Esops). Among them were Alok Goyal, redBus’s chief operating officer, and Satish Gidugu, the chief technology officer. “It was a unique phase for me in my journey,” remarks Kashyap. “There were challenges ranging from people, technology, culture and energy.” To cope with these, he decided to become more hands-on with the running of redBus. Kashyap also brought in Anoop Menon, one of Goibibo’s co-founders, as the redBus CTO and, upon Sama’s eventual exit in 2014, appointed Prakash Sangam, a former Airtel executive, CEO.

![mg_87339_ibibo_group_new_280x210.jpg mg_87339_ibibo_group_new_280x210.jpg]()

“When we took over, we had a startup with a proven business model, but we had to scale it up,” says Sangam. Since redBus was a startup, he points out, a lot of the technology was patched up to keep up with the volumes. The technological core was strengthened, and this shows in the results: redBus has continued to dominate the bus reservation segment with a claimed market share of 70 percent. The number of transactions, the company claims, has increased from around 600,000 a month, at the time of acquisition, to 2.1 million a month at present.

And there’s room for growth in a market where online penetration hovers between 15 and 20 percent, says Sangam. Besides, redBus is also present in Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia, and has big expansion plans ahead. “We’re furiously working on expanding in the next 3-4 months,” he says.

Another important acquisition in this context has been YourBus.in, a bus tracking platform that was acquired in 2014. “Four thousand buses on redBus are now tracked in real time,” says Kashyap. “Mobile has been one of the key growth drivers. Fifty-five percent of the transactions are taking place on mobile.”

With redBus’s volatility now a thing of the past, it is no longer on top of Kashyap’s mind. For now, his sights, and those of every other OTA in India, are set on the meatiest chunk of the travel pie: Hotels.

It is peak tourist season in Shimla, about 400 kilometres from where we’re seated. Vinayak Jishtu, a hotelier who runs a 20-room budget hotel in the hill town, prepares to welcome a fresh set of guests. “They come about once every month,” he says, of the “OTA people”. “They discuss rates, yields and commission percentages and try to get as many of our rooms as possible onto their platform.” You could call them foot soldiers in an ongoing revolution in Indian online travel. They trudge up to hotels of all kinds, maintain relationships with existing partners and, where needed, educate hoteliers about their customers and the potential of tech-enabled hospitality.

It is no secret that in the online travel space, hotels are where the money is. In 2014, online hotel bookings in India stood at $800 million, according to Phocuswright, a travel, tourism and hospitality research firm. Also, while air ticketing margins hover at about 5 percent, according to industry estimates, hotels can exceed 15 percent.

The commissions from airlines, meanwhile, have been steadily slimming over the years, explains Ashish Basil, partner, Transaction Advisory Services at consulting firm Ernst & Young India. “To overcome the fall in commission revenues, many of the OTAs, much before the budget hotel aggregation hype, had started focusing on the hotel and accommodation industry. That’s where the margins were,” he says.

True to form, Goibibo was a late entrant into the hotels segment, only arriving on the scene in 2013. Earlier that year, Kashyap had experienced first-hand the impact that inadequacies in the hotel reservations space could have. “I had booked a hotel on an OTA, printed the hotel booking voucher (like an e-ticket) and drove to Manali to spend the weekend,” he says. When he got there, he was denied a room. “The reason cited by the hotel manager was that they were sold out.”

The fundamental problems here were not hard to identify. The hotels weren’t using any technology and the customers did not find the platforms reliable, thanks in large part to experiences like his.

But addressing them wasn’t going to be easy. The supply of hotels in India is largely dominated by independent property owners, points out Chetan Kapoor, research analyst at Phocuswright. The previously mentioned Millward Brown report suggests that only 25 percent of all hotel reservations in India are made online. Of these, 7 percent are made through hotel websites and 18 percent are booked through OTAs.

“An airline purchase is based on a logo and a price. Hotels have a lot of parameters that consumers must evaluate. Due to the lack of standardisation and extreme fragmentation, OTAs have the opportunity to add greater value in this purchase process,” says Sandeep Murthy, partner at venture capital firm Lightbox and a board member at the OTA Cleartrip.

It is no surprise then that one of the first things that Kashyap and his team did with regard to hotels was to develop an application for hotel owners called Ingoibibo. It allowed them to manage inventory and receive data about yield, pricing as well as their performance compared to competitors. “We divided the country into 2,000 hyperlocal areas and put a ground team together to educate thousands of hotels in these hyper locations to adopt this application,” says Kashyap.

Besides the obvious benefits of a simplified inventory system and dynamic pricing, there was one other thing that Kashyap was looking to foster among hotel owners. By providing them with real-time information about other hotels in their vicinity, he says, “the competition effect drove a positive paranoia amongst the hotels.” This paranoia, Kashyap believes, was important. While the company offered a carrot with improved occupancy rates and possible better prices, the threat of losing out to the competition acted as the proverbial stick.

![mg_87335_ibibo_280x210.jpg mg_87335_ibibo_280x210.jpg]()

In a throwback to its time as a social media company, Goibibo also developed its own picture-based ratings and reviews component. It was a departure from the standard practice of letting customers use TripAdvisor for the ratings and reviews of hotels. It further increased the positive paranoia, Kashyap quips. It has also recently launched a ‘questions and answers’ section to enable customers to interact with each other.

All of these innovations are aimed at creating “double-sided network effects”, says Kashyap. ‘Network effect’, two words that internet companies adore, essentially refer to the growth in the value of a product with an increase in the number of people who use it. The double-sided bit refers to the fact that it applies not just to Goibibo’s consumers but also its suppliers—the hotel owners.

The challenge of a fragmented hotel segment remains. “The fundamental challenge is reaching some level of standardisation,” says GT Thomas Phillippe, partner at law firm Khaitan & Co, who is part of the firm’s ecommerce practice. “They’ll need to have some kind of control over the inventory that they’re selling.” In this regard, Goibibo has introduced GoStays, which is an attempt to certify properties and ensure that they have certain basic amenities. “We are using algorithms, our ground network and power of crowds to certify these unknown properties and at the same time deliver a reliable and standardised booking experience.”

Hotels, then, are at the centre of everything that the Ibibo Group does. In fact, according to figures shared by them, hotels contributed 41 percent to its gross sales, which stood at $1.67 billion in 2015. Air ticketing was a close second at 39 percent, while bus ticketing contributed 20 percent.

Besides its hotels push, the group has gone back to its ‘greenfield’ DNA to create another startup called ibibo Ryde. It’s a long-distance ride sharing platform, which has been created by a small team with the same restraints that were put on the one that created Goibibo.

In a departure from industry norm, Ibibo Group has a number of separate brands under its umbrella, occasionally with separate mobile apps. But there is a lot of integration on the back-end, says Kashyap. “Hotels published on Goibibo extend to redBus, bus listings aggregated by redBus extend to Goibibo and Travel Boutique Online and ibiboRyde inventory is published on redBus.”

Nine years after it began, Kashyap’s greenfield operation is now a large corporation. But its original purpose, it would seem, has been served. Though the Ibibo Group is now a pure-play travel and transportation company, it has seen the birth and occasional demise of quite a few ventures over time. When Goibibo first entered the online travel space, “they made life quite difficult for the incumbents,” says Murthy of Lightbox. “Any entrant into a market will start by competing using discounts.” And that was the case with Goibibo too. But, he says, in the long term, what will matter is the value that a brand builds for its customers.

Ask Kashyap about what lies ahead, and his answer is calculated: “The aim is to have a large percentage of accommodation owners to use our technology on one hand and to have consumers use our platform to make a booking, on the other.”

At the same time, online travel in India remains a crowded space, with both local players like Cleartrip and Yatra.com, as well as foreign ones like Expedia and Booking.com. Oyo Rooms is also considered a threat as evidenced from its exclusion by OTAs from their platforms. While Goibibo may have excelled in the hotels segment, MakeMyTrip remains the biggest bully on the yard. The Nasdaq-listed company’s net revenues for the fourth quarter of FY2015, which stood at $36.36 million (about Rs 250 crore), exceeded Ibibo Group’s revenues for that entire financial year (excluding redBus and Travel Boutique Online). And with the investment from Ctrip, it is set to fight hard to keep the top spot.

But if money can talk, then for now, Kashyap has a $250-million mouth. And though he speaks with restraint, he means serious business.