Dave Duffield is the software industry’s eternal teenager. Consider the way the 73-year-old smashed up his first company car. “It was in the 1960s,” Duffield ruefully tells me. “I was a young techie in a hurry.” After quitting a safe job at IBM, he hawked his own software for scheduling final exams more efficiently, zooming between college campuses in a Porsche Carrera loaded with punch cards in the back. At least, that was the plan for a few weeks. “I was in Binghamton [New York] on a freeway exit,” says Duffield. “It was foggy, and the tire slipped. I went through a telephone pole.”

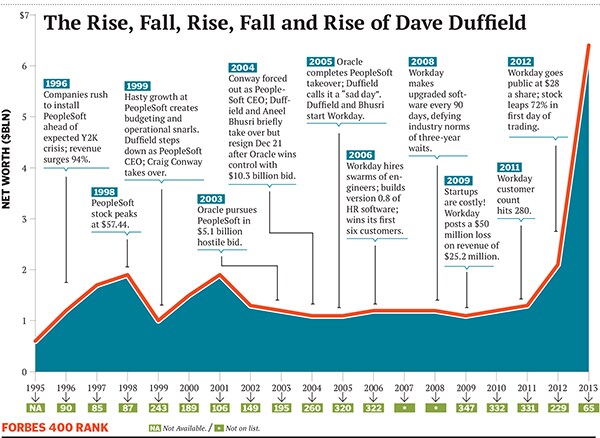

Duffield never slowed down. With his fourth startup he made his debut on The Forbes 400 in 1995, having amassed a $600 million fortune as the founder of PeopleSoft, which provided easy-to-use software for corporate personnel. PeopleSoft’s employees were as enthused as its customers—it won acclaim as one of America’s best places to work—but Duffield’s freewheeling style created a series of stumbles. In early 2005 PeopleSoft was swallowed up in a hostile takeover by Oracle, for $10.3 billion, leaving Duffield rich, morose and out of work.

PeopleSoft senior executives “had some sort of post-traumatic Oracle disorder”, recalls Salesforce.com CEO Marc Benioff, who met periodically with Duffield and his lieutenants to share strategy tips and rally their spirits. “They reminded me of a dog that got hit over the head too many times.” Duffield can smile now. His fifth startup is outpacing his fourth: Workday delivers human resource and financial software, just like PeopleSoft, but it does so in the world of the internet cloud, not traditional installations in corporate data centres. Workday has attracted customers such as LinkedIn and Thomson Reuters: Providing them with easier installation, faster updates, spiffier features and all the sleek graphics and iPad usability that consumer internet companies have made so popular. Even though the Pleasanton, California, company has yet to turn a profit, cloud-crazy investors have rewarded Workday with a $13 billion stock market valuation. Duffield’s 40 percent stake, combined with his previous investment portfolio, is worth $6.4 billion, more than triple what it was last year. Duffield has had the steepest rise on this year’s Forbes 400. How did the old guy do it?

The tech sector, unique among American industry, worships youth over experience. Disruption, the belief goes, comes from new generations of digital natives who are unburdened with knowing how things were or are. In 1998 Microsoft founder Bill Gates declared that his biggest worry was “someone in a garage inventing something I haven’t thought about”. No kidding. Google’s young founders, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, were just getting rolling at the time. A decade later it was the Google guys’ turn to be spooked, by Harvard dropout Mark Zuckerberg and the social media tornado he was creating with Facebook. Even Zuckerberg (now a doddering 29) is watching his back these days.

Tech’s white-haired veterans tend to shift to the quiet safety of angel investing and a few board seats. The evolution into older irrelevancy is soothed with the delights of a ski house in Tahoe, a rich suntan or a Porsche collection. Duffield fits all these into his life. But since 2005 he has been on a nonstop crusade to turn Workday into a winner.

In recent months Duffield has been spotted again on college campuses, from Florida to Illinois, pitching new Workday software that’s meant to make universities run better. His traveling habits have changed a bit: With a private jet he keeps the Porsches in the garage the primitive punch cards have been supplanted by invisible fiber-optic links. Yet the entrepreneur’s delight in signing contracts and wooing new prospects never fades.

Ask Duffield how he stays ahead of the kids and his first answer is coy: Don’t eat too much. “I just don’t like being overweight,” says the man who can still slip into 32-inch-waist Levis with ease. His latest success starts with a willingness to chase the big opportunity, he says. Helping the cause is extra wisdom gleaned from many years of experience. Most important, Duffield says, is finding the right partner—in this case, 47-year-old Aneel Bhusri.

Duffield and Bhusri met 20 years ago, when the younger man was wrapping up his MBA at Stanford and toying with the idea of heading east for a venture capital job. Don’t do it, Duffield told him over a beer. Come explore ways we can make PeopleSoft grow. Duffield’s starting pay of $70,000 was barely half what Bhusri could have made in consulting or on Wall Street. But Bhusri took the job anyway, excited about the fast-paced opportunities that Duffield offered. Smart call. Bhusri is nearly a billionaire himself, serving as co-chief executive with Duffield and holding a 6.9 percent stake in Workday.

Year by year the two men have been adjusting the way they split Workday’s command. A few years ago, Duffield says, it was 50-50. Now, “Aneel is 80 percent of the CEO job, and I’m 20 percent.” Bhusri demurs, but the best perspective comes from Workday director Skip Battle. “It will always be the Dave and Aneel Show to the outside world, because of Dave’s age and visibility,” Battle says. “But if you were buying key-man insurance, you’d pay the highest premium for Aneel.”

What’s most striking is that Bhusri—the relative youngster—has become the grown-up in this rela- tionship. He’s the careful driver with the map, setting Workday’s strategy and making sure it gets there. The contrast is obvious at Workday’s customer events, where Bhusri opens the show with a fact-filled update on products. When Duffield takes the stage, he hurls snack food into the audience and provides a peek at his— gasp!—purple “skivvies” to bear out the point that they were bought from Primark, a Workday customer.

By revenue Workday is still a pip- squeak in enterprise software. The entrenched giants are Oracle and SAP, with combined annual revenue of about $50 billion. Workday’s current annual run rate is only $400 million, not even 1 percent of the big guys’ pace. What gets investors so excited is the possibility that little Workday might have a lasting edge in defining the future of enterprise software.

Morgan Stanley software analyst Jennifer Swanson Lowe surveys Oracle customers to see what their next move might be. In her last such poll, in May, 10 percent of Oracle users said they plan to switch to Workday—and another 29 percent said they want to take a closer look at the new guy’s offerings. Her conclusion: “Workday’s growing mind-share could be a strong tailwind for growth.” A Goldman Sachs forecast has Workday crossing the $1 billion revenue mark in two-and-a-half years.

The old guard isn’t standing still. After dismissing cloud mania as “nonsense” in 2009, Oracle CEO Larry Ellison recently has become a cloud enthusiast, buying full-page magazine ads to tell people about his company’s many initiatives in this area.

It’s a similar story at SAP, where co-CEO Bill McDermott this summer talked about potential customers “radically shifting their businesses to the cloud”.

Duffield and Bhusri see the world like the twenty-something bomb-throwers they are assuredly not: Workday’s brief history and small size isn’t a handicap—it’s a huge advantage.

“You have to start with a clean sheet of paper,” Bhusri explains. “There’s just no way around it. Every time you see a new paradigm emerge, it’s always new vendors that lead it. I can’t think of one case where an incumbent led a paradigm shift. There are too many obstacles with legacy [computer] code and thousands of customers. It’s really hard to move.”

Even PeopleSoft couldn’t avoid big-company torpor in its final years. To Duffield’s chagrin a 1999 attempt to create radically new software petered out. By 2004 something as simple as upgrading customers to the next generation of software stopped being simple. Bureaucracy and bloat got so bad that Bhusri became convinced that enterprise software was ready for a new way of doing things. Oracle’s hostile raid left them no other choice.

The seeds for Dave Duffield’s vindication were sown over brunch at Truckee, California. It was February 2005, and Ellison had simultaneously stripped Duffield and Bhusri of their positions and filled their pockets with cash. Bhusri was the provocateur, laying out the case for a new company that would sell a single version of cloud-based software. Also on tap: Big changes in systems architecture and user interfaces that would make the software much easier to update and much friendlier to use. If the two men succeeded, they might create something bigger and better than PeopleSoft. If they failed, “we’d have ended up with a smoking crater”, Bhusri later observed.

Duffield—the eternal risk-taker— couldn’t resist. A few weeks later he decamped from the Incline Village, Nevada, mansion that he had intended to retire in and relocated to his old working grounds 20 miles east of San Francisco. “I think I’ve got one more in me,” Duffield told a long-time PeopleSoft deputy, Stan Swete, when they bumped into each other at an East Bay grocery store.

Word spread quickly among the old PeopleSoft crew that Dave was back. Within weeks engineers who had built their careers with Duffield were setting up Ikea folding tables in makeshift offices. Duffield became the firm’s sugar daddy, covering first-year costs with a $15 million personal cheque. The less liquid Bhusri pitched in a few million later on. In this case experience paid: Workday’s earliest customers consisted mostly of midsize-company CEOs who knew the founders. “They bought the friendship, not the software,” Duffield now says.

Duffield also helped set the same competitive, fun-loving culture that had been a big part of PeopleSoft’s early success. He bought pool tables for Workday’s East Bay and San Francisco offices. (He had been a champion pool player as an under-graduate at Cornell.) He celebrated each new child born to a Workday employee, keeping a running tally of all the Work-babies.

Duffield has 10 kids himself, three biological and seven adopted, and starts his day by running to school with his 3-year-old daughter. And he taunted Workday’s bigger rivals with mischief such as YouTube videos mocking SAP and Oracle.

All the while Workday’s engineers were building software powerful enough for a Forbes Global 2000 giant, even if the company didn’t yet have such customers. That meant making it easy to record employees’ religion in Britain, blood type in India, disability status in Germany or familial home district in China. Says Karen Beaman, an early Workday employee, “Our data structures had to accommodate both global and local needs.”

Workday’s earliest software wasn’t pretty, but every 90 days a better ver- sion emerged. Upgrades were smooth, especially when compared with pre- Workday tussles as customers reaped the benefits Bhusri foresaw from using the same centrally maintained code. As Workday grew, its more ad- vanced versions passed muster with the Global 2000. Chiquita Brands and Flextronics came on board. The likes of Philips, Time Warner and Hewlett-Packard followed.

Bhusri, a part-time venture capitalist at Greylock Partners when he isn’t spending time at Workday, became known as the company’s product expert. Some of his insights come from Silicon Valley, others from chats with customers or front-line engineers. “Aneel has this deep intellectual curiosity,” says Reid Hoffman, a Greylock partner and the chairman of LinkedIn. “He’s like a fisherman, casting for ideas. And he’s very encouraging, so people tell him a lot.”

One early test came when Duffield declared he didn’t want Workday to build a payroll system. Too complicated, he said, and they hadn’t worked well at PeopleSoft. Bhusri consented for a bit but warned, “We’re going to have to do it before long. Customers will insist on it.” He and Duffield made a small bet about who might be right. Workday’s seventh customer, McKee Foods, took the must-have stance that Bhusri had predicted. Payroll became part of the Workday lineup.

![mg_72293_dave_duffield_280x210.jpg mg_72293_dave_duffield_280x210.jpg]()

More often Bhusri and Duffield have tugged Workday in the same di- rection. In April 2010 Bhusri became a first-day buyer of the first iPad—and called Duffield to tell him: “This is going to be huge. It’s a game-changer for us.” Duffield got his own iPad soon afterward and concurred. Before long Workday had a 10-person mobile team, reporting to Bhusri, that devised a slew of HR functions that were meant for the iPad alone. Tasks like filing expenses, approving new hires or analysing regional profitability can now all be done while on the go.

Workday’s mobile chief, Joe Korngiebel, explains that iPad friendly software isn’t just a convenience it also greatly increases employees’ willingness to do tasks themselves, rather than jamming HR and finance departments with unwanted paperwork. That lowers customers’ overall operating costs, making Workday a more compelling buy. And the faster that Workday racks up subscriptions, the better its business looks.

Workday’s software isn’t cheap. A three-year subscription to the com- pany’s HR or financial suite can run $100 to $200 annually per employee. Contracts of $800,000 a year are common multi-million-dollar orders are increasingly part of the mix.

Customers can save as much as 40 percent versus traditional software on overall costs, Workday contends, because upgrade and installation fees are so much lower. Deloitte, which does a lot of Workday installations, says savings for big companies do exist, but they are more likely to be in the 10 percent-to-30 percent range.

With its big engineering and sales costs, Workday posted a $36 million loss in the quarter ended July 31, on revenue of $108 million. But investors seem willing to focus on more lenient metrics that give the company credit for subscription revenue that won’t be collected for months or years. Bulls also note the company has more than $1 billion in cash, thanks to two big convertible bond sales and its October 2012 IPO.

Workday raised a hefty $250 mil- lion in equity before going public, and while Duffield took his big position early—when the risks were greatest and the stock cheapest—an interesting assortment of big-name investors pumped more money into the company at higher valuations shortly before the IPO. They include Bhusri’s colleagues at Greylock, Morgan Stanley, T Rowe Price and New Enterprise Associates, and tech legends Michael Dell and Jeff Bezos.

As Bhusri tells it, he button-holed Bezos one year at Allen & Co’s summer get-together in Sun Valley, Idaho. After 15 minutes Bezos told him: “Fine. I’ll invest.”

“Don’t you want to hear more?” Bhusri asked.

“No,” Bezos replied. “I’ve heard all I need.”

Workday’s oldest salesman, Duffield, remains its most effective. “We met for two hours the first time, and Dave was as humble and authentic a person as I could have hoped for,” says David Armstrong, president of Broward College in Florida. Duffield didn’t just offer charm he also invited Armstrong to suggest product ideas.

That’s led to brainstorming about software that can automatically text students who might be falling behind to urge them to get extra tutoring. It also led to a multimillion-dollar contract.

“If you truly listen to what people are saying, you’ll find out what’s on their mind that they want to be comfortable with,” says Duffield. “And then you’ll be more effective in addressing their concerns.” Simple advice, but it’s often the difference between outstanding salespeople and ones who can’t understand why they’re having such a hard time closing the deal.

As Workday grows, Duffield’s role will likely shift toward mentor- ing, boardroom oversight and special projects. “I could see myself reporting to Aneel in a couple years,” Duffield says. His younger partner shoots back: “And it’s my job to try to postpone that switch for as many years as possible.”

One worry that Duffield and Bhusri won’t have this time around is the risk of a hostile takeover. While their company has lots of investors, as a practical matter, the two co-founders are the only owners that matter. Their holdings are concentrated in supervoting Class B shares, which give them 72 percent voting control of the company.

They didn’t have anything like that at PeopleSoft, and they say they’ve learned their lesson. This time around, says Duffield, “we control the voting rights in spades”. And he has no plans to go anywhere anytime soon.