The optometrist who beat the odds to become a billionaire

Amid stock market booms and busts, and game-changing innovations from ETFs to algorithmic trading, a Florida optometrist could be the greatest inventor you never heard of

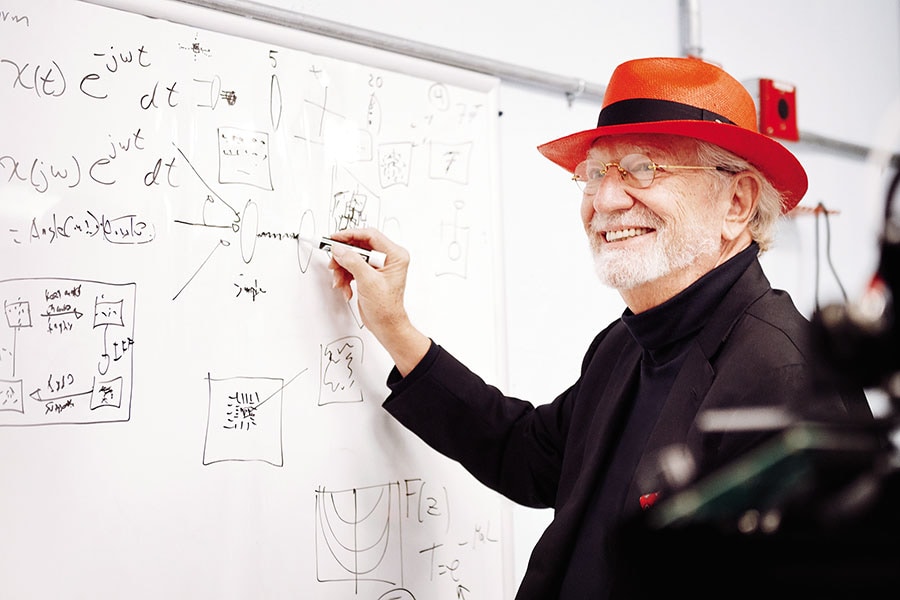

Dr Herbert Wertheim occasionally lectures on engineering at Florida International University. He should be teaching finance

Dr Herbert Wertheim occasionally lectures on engineering at Florida International University. He should be teaching finance

Image: Jamel Toppin for Forbes

It’s 9 pm on the last Saturday night of the 2018 Art Basel in Miami Beach. On the first floor of the palatial Versace mansion, the well-dressed and well-Botoxed are dancing to remixes of Michael Jackson’s ‘Beat It’ and posing for Instagram by the mosaic-tiled emerald pool.

Upstairs, in a VIP room decorated in a mélange of styles that marry classical Greek and Roman touches, a well-dressed septuagenarian named Herbert Wertheim is sitting in front of a plate of smoked-salmon toast topped with gold leaf and shaved truffles, and scrolling through photos on his iPhone—scenes from what could only be described as a wonderful life. There are fan photos of him cooking pasta fagioli with Martha Stewart, on the slopes with Buzz Aldrin and fishing in Antarctica. There are many with his wife of 49 years, Nicole, on the luxurious World Yacht, where the Wertheims now live part of each year. He calls these extracurricular activities “Herbie time”.

If it weren’t for his trademark bright-red fedora, Wertheim, who is an optometrist and small businessman, would look like the typical senior living it up in South Florida.

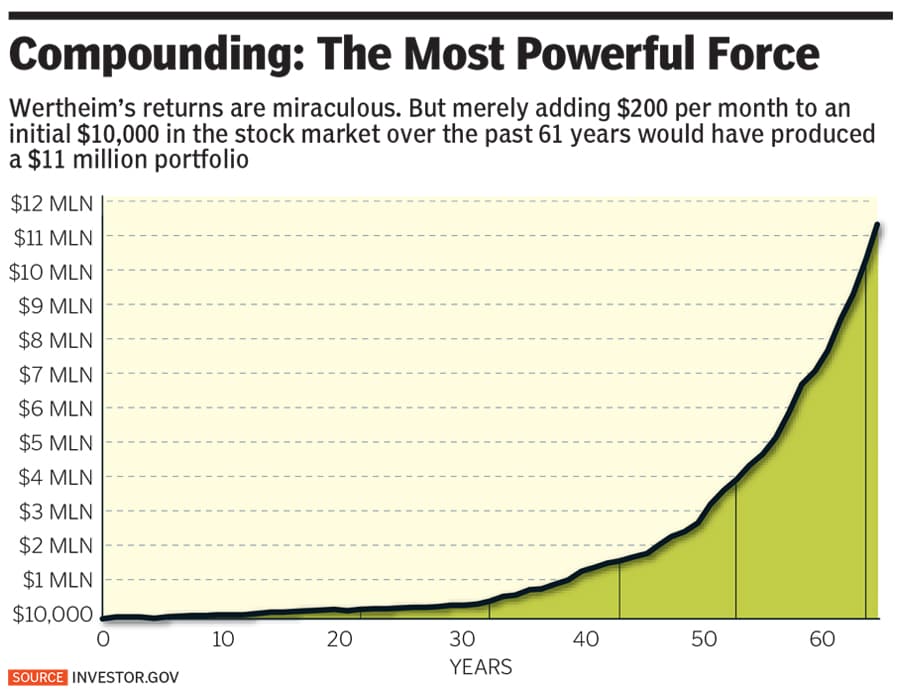

But Wertheim, 79, has no need for early-bird specials. What the photos don’t reveal is that Dr Herbie, as he is known to friends, is a self-made billionaire worth $2.3 billion by Forbes’s reckoning—not including the $100 million he has donated to Florida’s public universities. His fortune comes not from some flash of entrepreneurial brilliance or dogged devotion to career, but from a lifetime of prudent do-it-yourself buy-and-hold investing.

Herb Wertheim may be the greatest individual investor the world has never heard of, and he has the Fidelity statements to prove it. Leafing through printouts he has brought to a meeting, you can see hundreds of millions of dollars in stocks like Apple and Microsoft, purchased decades ago during their IPOs. A $800 million-plus position in Heico, a $1.8 billion (revenue) airplane-parts manufacturer, dates to 1992. There are dozens of other holdings, ranging from GE and Google to BP and Bank of America. If there’s a common theme to Wertheim’s investing, it’s a preference for industry and technology companies and dividend payers. His financial success—and the fantastic life his portfolio has afforded his family—is a testament to the power of compounding as well as to the resilience of American innovation over the last half-century.

“My thing is,” Wertheim says as he reflects on his long career, “I wanted to be able to have free time. To me, having time is the most precious thing.”

*****

Born in Philadelphia at the end of the Great Depression, Wertheim is the son of Jewish immigrants who fled Nazi Germany. In 1945 his parents moved to Hollywood, Florida, and lived in an apartment above the family’s bakery. A dyslexic, Wertheim struggled in school and soon found himself skipping class.

“In those days, they just called you dumb,” he remembers. “I would sit in the corner sometimes with a dunce cap on.”During his teens, in the 1950s, an abusive father prompted Wertheim to run away periodically. He spent much of his time hanging around with the local Seminole Indians, hunting and fishing in the Everglades and selling game, like frog legs, to locals. He also hitchhiked around Florida picking oranges and grapefruits.

Eventually, his parents had enough. At 16, he stood in front of a judge facing truancy charges. Lucky for Wertheim, the judge took pity on him, offering him a choice between the US Navy and state reformatory. Wertheim enlisted in 1956 and was stationed in San Diego. He was only 17.

“That’s where my life changed,” he says. “They give you tests all the time to see how smart you are, and out of 135 in our class, I think I was in the top—especially in the areas of mechanics and organisation.”

With a newfound confidence, Wertheim studied physics and chemistry in the Navy before working in naval aviation. This is about the time Wertheim began investing in stocks. It was the Cold War, the military-industrial complex was humming and American industry was on the move. The Dow Jones Industrial Average had finally recovered from the losses it suffered more than two decades before during the Crash of 1929, and aerospace stocks were leading the market.

Wertheim made his first investment at 18, using his Navy stipend to buy stock in Lear Jet, which at the time was known for making aviation products during WWII.

Wertheim met its founder, Bill Lear, during a visit to a Sikorsky Aircraft factory in Connecticut, where the Navy’s S58 helicopters were manufactured. Wertheim was attracted to Lear’s inventions, like the first auto-pilot systems. (Later, the company would invent the 8-track tape and pioneer the business-jet market.)

“You take what you earn with the sweat of your brow, then you take a percentage of that and you invest it in other people’s labour,” Wertheim says of his near-religious devotion to tithing his wages into the stock market.

Once out of the Navy, Wertheim sold encyclopaedias door-to-door before attending Brevard Community College and then the University of Florida, where he studied engineering but never graduated. In addition to taking classes, he worked for Nasa—then in its first few years—in a division that improved instrumentation for manned flights. This fuelled an interest in the eye and instruments optimised for vision.

In 1963 he received a scholarship to attend the Southern College of Optometry in Memphis and after graduation opened up a practice in South Florida. For 12 years he toiled away, seeing patients who were mostly working-class and who sometimes paid their bills with bushels of mangoes and avocados. Wertheim spent his evenings tinkering on inventions, and in 1969, he invented an eyeglass tint for plastic lenses that would filter out and absorb dangerous UV rays, helping to prevent cataracts.The Vietnam War was underway, and plastics had become the material of choice for eyeglasses and sunglasses. Demand for Wertheim’s tint grew, and he sold it in a royalty deal for $22,000. But because of contractual breaches, the royalties never materialised.

So in 1970 Wertheim decided to get more serious about his inventions and set up a new company, Brain Power Inc. He founded it as a technology consulting firm, but Wertheim soon returned to his habit of researching and tinkering, developing tints, dyes and other technologies for eyewear.

A year later he concocted one of the world’s first neutralisers, a chemical that restored lenses back to their original clear state. This meant opticians no longer needed to carry large inventories of different-coloured lenses or dispose of lenses that were improperly tinted. “I was still seeing patients, I had a little lab,” recalls Wertheim. He showed his wife a coffee can containing his chemical concoction and said, ‘Nicole, what’s in this can is going to make us millionaires’.”

It did. Between that chemical and the numerous other products Wertheim invented for lenses—some tints for aesthetics, others to help ease the symptoms of neurological disorders like epilepsy and still others to improve UV protection—BPI became one of the world’s largest manufacturers of optical tints, selling to companies like Bausch & Lomb, Zeiss and Polaroid. The company also began making lab equipment, cleaners and accessories for opticians, optometrists and ophthalmologists. Today BPI has more than 100 patents and copyrights in the area of optics, 49 employees and annual revenues of about $25 million.

In less than two decades, Wertheim had gone from ne’er-do-well to inventor and entrepreneur. BPI never achieved hypergrowth, but it provided a steady net income amounting to some $10 million a year, according to Wertheim, more than enough to feed his passion for investing and the good life.

“I didn’t want to have a big business,” he says. “But today, I have a 5 or a 6 or an 8 billion-dollar corporation, each of which I own 10 percent of.”

*****

With BPI cash flowing into Wertheim’s brokerage account, he went to work buying stocks and honing a strategy that can best be described as a mix of Warren Buffett and Peter Lynch, with a touch of Jack Bogle, given that he dislikes fees and primarily uses two discounters, Fidelity and Schwab, to manage his massive portfolio.With Lear Jet (later known as Lear Siegler) in the late 1950s, for example, Wertheim was practicing “invest in what you know”, the strategy popularised by the famous Fidelity Magellan fund manager Peter Lynch in his 1989 book One Up on Wall Street.

Instead of concentrating on the metrics in financial statements, Wertheim is devoted to reading patents and spends two six-hour blocks each week poring over technical tomes. “What’s more important to me is, what is your intellectual capital to be able to grow?” Thanks to his engineering background, the technical nature of optometry and his experience as an inventor, the patent library is Wertheim’s comfort zone. Stocks he invested in based on their impressive patent portfolios include IBM, 3M and Intel.

Like Warren Buffett, Wertheim believes firmly in doubling down when his high-conviction picks go against him. He says that if you put your faith in a company’s intellectual property, it doesn’t matter too much if the market goes south for a bit—the product, he believes, has lasting value.

“If you like something at $13 a share, you should like it at $12, $11 or $10 a share,” Wertheim says. “If a stock continues to go down, and you believe in it and did your research, then you buy more. You are actually getting a better deal.” Whenever possible, he adds, dividends are useful in cushioning the pain of stocks that drift down or go sideways.

“My goal is to buy and almost never sell,” he says, parroting a Buffettism. “I let it appreciate as much as it can and use the dividends to move forward.” In this way Wertheim, like the Oracle of Omaha, seldom reinvests dividends but instead uses the cash flow from his portfolio to either fund his lifestyle or make new investments.

Wertheim points to Microsoft, a stock he has held since its IPO in 1986. “I knew a lot about computers and had been involved in building them,” he says. BPI had been using Apple IIe’s, but after Microsoft released its Windows operating system in 1985, Wertheim became convinced it would be a winner. “Only Microsoft had an operating system that could compete with Apple,” he recalls. The Microsoft shares he bought during the IPO, which have been paying dividends since 2003, are now worth more than $160 million. His 1.25 million shares of Apple, some purchased during its 1980 IPO and some when the stock was languishing at $10 in the 1990s, are worth $195 million.

Not all of the hundreds of stocks he has owned have fared so well. He invested big in BlackBerry. “I believed in the new management and the recovery story,” says Wertheim, who will generally sell if a position reverses on him by 25 percent. “I watched substantial profits disappear month after month until I decided enough was enough.”

Wertheim sometimes uses leverage, but mostly in a limited way when buying high-yielding stocks. “By using the dividends to offset [the cost of] margin interest, the government is helping you increase your portfolio value,” he explains.

But in 1982 Wertheim got caught in a margin call after Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker raised the federal funds rate from 12 percent to 20 percent and the market sank 20 percent. The episode cost him $50 million and taught Wertheim a valuable lesson about the dangers of leverage and mark-to-market accounting. Like most other active investors, Wertheim strives for tax efficiency. In order to harvest tax losses in his portfolio, he doubles down on his losers to avoid the IRS’ wash-sale penalties. “If I have a large loss in a stock I like,” he says, “I will purchase more, usually twice to three times the original purchase, and wait the 30 days to sell the original position and book the tax loss.”

As with Buffett, Wertheim says finding companies with strong management has been key to his success. A great example of this is Heico, a family-run aerospace and electronics company based in Hollywood, Florida.

*****

Wertheim became friendly with Laurans “Larry” Mendelson during the 1970s, after Wertheim bought a condominium in a building Mendelson owned and docked his boat next to Mendelson’s on Coral Gables Waterway. “He has two daughters around the same age as my two sons,” Mendelson says. “We got to know each other socially.”A CPA by training, Mendelson was a successful real estate investor who had studied at Columbia Business School under David Dodd, co-author with Benjamin Graham of the seminal book on value investing, Security Analysis. Inspired by the wave of dealmakers getting rich from LBOs in the 1980s, the Mendelsons were looking to find an undervalued, underperforming industrial company to take over.

After they settled on Heico, at the time a small airline-parts maker, Wertheim used his aeronautical knowledge to informally help the family analyse its business and went on to purchase shares of the company—a penny stock priced as low as 33 cents.

“At that time Heico was a disaster, but he came up and understood what we would do to make it a non-disaster,” says Mendelson.

Heico was making narrow-body jet-engine combustors, which the FAA mandated be replaced on a regular basis after a plane caught fire on a runway in 1985. Under the Mendelsons, Heico expanded its line of replacement parts, which undercut established original-equipment manufacturers like United Technologies’ Pratt & Whitney and GE. After Germany’s Lufthansa acquired a minority stake in the company in 1997, airline manufacturers and Wall Street took notice, and its share price rose sixfold to more than $2. But this was just the beginning. Heico enjoyed a proverbial moat as one of only a few FAA-approved airplane replacement-parts manufacturers. This translated into steadily growing orders as Heico expanded its product mix and as demand for air travel increased. For the last 28 years, Heico’s sales have compounded at a rate of 16 percent per year and its net profits at 19 percent.

Today, Heico trades for $80, and buy-and-hold Herbie is its largest individual shareholder. His original $5 million investment is worth more than $800 million.

*****

As Wertheim enters his 80th year, Herbie time has become his chief preoccupation. Besides his $16 million oceanfront home in Coral Gables, Wertheim has a 90-acre ranch near Vail, Colorado, a spectacular four-storey home overlooking the Thames in London and two sprawling estates in southern California. He spends many winters with his wife and family vacationing aboard World Yacht, the planet’s largest luxurious residential ship continuously circumnavigating the globe, where he owns two luxury apartments.

A signee of Bill Gates and Warren Buffett’s Giving Pledge, Wertheim has committed to giving away at least half his wealth, and he intends the bulk of the donations to go to public education—the very system of which he is a product.

“I would not have achieved the education and opportunities that I have had without the help of our public-university education system,” he wrote when he signed the pledge.

Stroll around Florida International University’s main campus, just minutes from Wertheim’s Coral Gables home, and you can’t help but notice buildings emblazoned with his name: The Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine, the Nicole Wertheim College of Nursing & Health Sciences, the Herbert & Nicole Wertheim Performing Arts Center and the Wertheim Conservatory. He has given $50 million to FIU and committed another $50 million to the University of Florida. Last year he pledged $25 million to the University of California, San Diego, to help create a school of public health. Beyond education, Wertheim says he’s given to hundreds of domestic and foreign non-profits, including the Miami Zoo and the Vail, Colorado, public radio station.

The former truant and class dunce still gets giddy when he sees his name on the university buildings, asking passersby to take photos—posing in his signature red hat and new Nikes. At the medical school, he put on a stethoscope, excited to test out the latest medical dummies, which breathe, sweat and even talk. In a room designed to study obstetrics, he tries his hand at an ultrasound machine. At a lab that he helps fund, he is enamoured with laser imaging and how it can help measure retinal temperature in the eye. At the FIU performing arts center bearing his name, he suggests adding an outdoor amphitheatre.

“He’s inspirational in the way he challenges people to think big and imagine what’s possible,” says Cammy Abernathy, dean of the Herbert Wertheim College of Engineering at the University of Florida.

Wertheim recently doubled down on British energy giant BP and now owns over one million shares. But rather than dwell on its sagging, crude-dependent stock chart, he’s betting on its hydrogen fuel cells and enjoying its 6 percent dividend yield while he waits for the company to recover.

“They have important intellectual property in that area,” he says of the cells, which create electricity by using hydrogen as fuel, a technology he believes is the future of both air and road transportation. “We’re going to move to a hydrogen economy.”

Contrarian Wertheim also likes the troubled stock of General Electric he owns over 15 million shares and has been picking up more. He says he is making a long-term bet on GE’s intellectual property the 126-year-old company has more than 179,000 patents and growing. Wertheim is especially jazzed about some patents that involve the 3-D printing of metal engine parts.

“You can’t look at what their sales are. You can’t look at anything. What is the future?” he says. “I feel very, very comfortable with GE because of their technology.”

And Wertheim isn’t in any rush. Playing the long game is what he does best.

First Published: Apr 02, 2020, 16:29

Subscribe Now