'Likes' lead to nothing-and other hard-learned lessons of social media marketing

A decade-and-a-half after the dawn of social media marketing, brands are still learning what works and what doesn't with consumers

It can be tough to pinpoint a direct connection between a social media chat about a product with the actual purchase of that product

Image: Shutterstock

Seventeen years after the dawn of social media marketing, this medium continues to be an intriguing puzzle—a place where brands are investing more time and money, but are still struggling to determine what works well and where the returns on investment can be found.

Social media spending has increased by 200 percent in the past eight years, rising from 3.5 percent of marketing budgets in 2009 to 10.5 percent in February 2017, according to The CMO Survey 2017. And that upward climb is expected to continue: Marketers say they will expand their social media spending by 90 percent over the next five years, or 18.5 percent of the total by then.

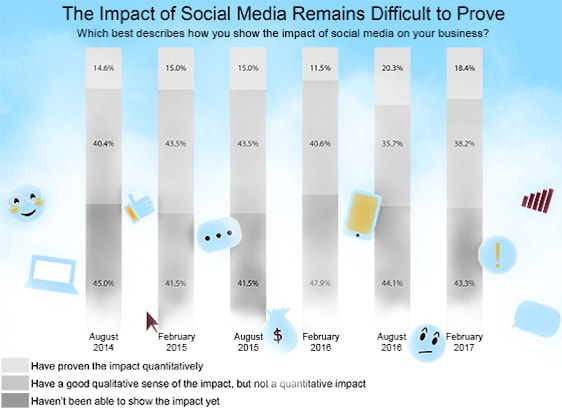

“All brands, big and small, are firmly in social media today,” says Jill J. Avery, senior lecturer at Harvard Business School. “Social media has become a mainstream tactic.” Marketing professionals are not sure that social media marketing is effective. Graphic by Blair Storie-Johnson (Source: “The CMO Survey 2017”).Is this ever-increasing focus on social paying off? Forty-three percent of respondents said in the CMO Survey that they have not been able to show the impact of social media on their businesses. After all, it can be tough to pinpoint a direct connection between a social media chat about a product with the actual purchase of that product.

Marketing professionals are not sure that social media marketing is effective. Graphic by Blair Storie-Johnson (Source: “The CMO Survey 2017”).Is this ever-increasing focus on social paying off? Forty-three percent of respondents said in the CMO Survey that they have not been able to show the impact of social media on their businesses. After all, it can be tough to pinpoint a direct connection between a social media chat about a product with the actual purchase of that product.

“The biggest challenge right now is that all this money is shifting into digital marketing, but there are still a lot of questions about return on investment,” Avery says. “Social media marketers are feeling pressure to show ROI.”

Still, since those first Facebook ads were posted in 2004, social media has proven itself a valuable tool for helping companies create consumer perceptions about particular brands (Old Spice) and has even sparked social movements (Ice Bucket Challenge). More recently, it has allowed companies to reap creative ideas on product improvements directly from their customers (Lay's flavored potato chips). And it has also managed to get brands into trouble (United Breaks Guitars).

As marketers have experimented, what have they learned about what works on social? We sat down with four marketing experts on the Harvard Business School faculty to find out.

WHERE BRANDS HAVE GONE WRONG

Here’s a look at some of the social media missteps brands have taken over the past decade–and the lessons we’ve learned from them.

Prioritizing technology over substance

Maybe it’s because the medium seems so ephemeral, but digital brand managers are too often intent on creating short-term promotions rather than conveying long-lasting brand values in the minds of consumers, says Sunil Gupta, the Edward W. Carter Professor of Business Administration.

As an example, take a look at location-based mobile marketing. “You walk past a restaurant, and McDonald’s sends you a 50-percent-off coupon,” Gupta says. “We’ve been doing that forever with a poster in the window I can have a guy stand in the doorway and hand you coupons. What’s the difference? We get caught up in the activity and never stop to ask: What is the benchmark?”

Early on, many brands made the mistake of focusing on collecting reams of likes on Facebook, yet Gupta says those likes haven’t amounted to much—certainly not a whole lot of purchases. “Do likes lead to loyal consumers or do loyal consumers tend to like a brand on Facebook? Do these likes lead to anything?” he asks. “What we found with our research was that likes lead to nothing.”

Not social enough

Commercial appeals often fall flat on social networks, which many consumers believe should be a place for conversations strictly among people they know. “If you and I are having a conversation and someone pulls up a third chair and says, ‘Buy my product,’ it’s annoying,” says Gupta.

Brands should instead look to create a conversation with a broader message that connects with consumers. For instance, Dove’s Real Beauty campaign wasn’t focused merely on the benefits of a bar of soap, but tapped into the deeper themes of body image and self-esteem that resonated with women.

“If a brand wants to create a conversation with you, the message of the brand has to be broader than just the function of the product itself,” Gupta says. “In social media, functional messages don’t work. I’m not interested in talking to my friends about a brand. So how can you weave the message into a bigger social conversation and still make it relevant to the brand?”

Forgetting that on the Web, consumers control your brand

With traditional marketing, brand managers took time to carefully craft messages placed in newspapers, television, and radio—and they had some control over who saw or heard that ad.

Now, marketing is much less manageable, with consumers taking charge of social media discussions about brands. Social gives customers a megaphone, Gupta says, allowing them to weigh in on every message a brand posts—all for plenty of public eyes to see.

Inappropriate messaging

Cheerios attempted to express sympathy after Prince died, but its “Rest in peace” tweet received a vicious backlash—and was later deleted—after the brand dared to dot the “i” in that message with a single Cheerio.

“This was a death that was felt very deeply by the fan culture of Prince, and that’s not a time for a heavy marketing sell,” Avery says. “A common tactic right now is for brands to look at what’s hot, what’s trending, and what’s in the news and they shackle their brands to it. If you’re just tacking your brand onto a current event that has no relationship to your brand or consumer, it’s dangerous because it can feel false, opportunistic, and inappropriate.”

Failing to understand how quickly things can go wrong

One viral video on Facebook can do serious damage to a company’s reputation, as United Airlines undoubtedly learned when a Facebook video surfaced of a passenger being dragged off an airplane.

“Social media has changed consumers’ expectations with the way they communicate with brands,” says Leslie K. John, Marvin Bower Associate Professor. “I have friends who have had a bad customer experience, and they immediately turn to Twitter.”

Some companies worry about even stepping into the social space for fear of how customers will react, but Gupta questions whether that’s a sign these companies really have a more general image problem that needs to be addressed.

“A health care company might say we wouldn’t have a social media conversation with consumers because consumers would say bad things about us,” Gupta says. “So, then you should ask: Why would they say those things? Is your company bad? If your (company) is lousy, a negative message will resonate with other people.”

WHERE BRANDS HAVE GONE RIGHT

Respond to complaints—and make it quick

Brands should react to social media negativity the same way firefighters manage forest fires, particularly when they’re not sure where the next spark will come from, Gupta says. “You ask these guys: How do you manage lightning strikes when you can’t predict them?” he says. “They have two simple rules: Make sure your forest is not dry, and if lightning strikes, act very quickly.” By ensuring that a forest is not dry, Gupta means companies should make sure they are perceived positively before a crisis occurs.

The Transportation Security Administration works to keep its forest dry by doing quite a bit of listening on Twitter. To ease congested lines at airports, for example, TSA workers answer questions online about items that can or can’t be carried aboard planes—a bit of helpful pre-planning communication many flyers appreciate.

When companies do screw up, social can make things worse or make things better in a hurry.

“In social media, seconds count,” Avery says. “If a company doesn’t respond in real time, other consumers will pile on and it spirals out of control.”

If a company has a positive reputation, customers will often defend a brand that’s feeling social media heat. A popular brand like Apple will have plenty of die-hard fans willing to push back when a consumer issues an online attack, Avery says. “The best defense against people who are speaking badly about you on social media is to have an incredibly loyal relationship with your users, so they are ready and able to defend you.”

It’s OK to be funny—but remember your brand’s purpose

Social media is a place where people appreciate humor—as long as it fits with the brand image, Avery says. Squatty Potty does an excellent job of engaging its audience with amusing and entertaining Facebook videos to sell a product focused on a subject people don’t normally like to talk about. Blendtec captured attention and increased sales with a video showing that its blender was so powerful it could crush a cell phone into a pile of powder.

“It went viral because it was short and it was shocking and funny,” Gupta says. “But it also had an objective and stayed on message: The blender (can) blend anything. That’s what social media should do: You can be funny, but you have to stay on message.”

Be playful, have fun

When brands get playful on social media, payoffs can be huge.

Every few years, a 2008 video recirculates on Facebook that appears to be dramatic footage taken with a handheld camera of a stunt plane losing a wing and spiraling to earth—with the pilot miraculously making a safe landing.

“It gets millions of viewings, and people pass it on. It seems too good to be true,” says John Deighton, Baker Foundation Professor of Business Administration. The video is so dramatic it is likely that many viewers will investigate further. “Some notice that the plane has a logo.”

Sure enough, it turns out that the clip was a digitally produced video promotion for German clothing company KillaThrill—the name on the logo. “Two-thirds of people who see it won’t ever know it’s an ad,” Deighton says. “But the people who see what it’s for and get to the company website are quite likely to buy something. They’ve tracked it down, and now you’ve got this bond, and you’ve engaged with a brand in a self-directed way.”

More recently, Wendy’s has taken a lighter touch on Twitter with customers:

Wendy's on Twitter

Put your customers to work

Brands can make consumers feel empowered by giving them opportunities to share ideas, as Lay’s has done by asking its customers to vote on the chip flavor the brand should create next.

“This is a new trend, and it provides great information, allowing companies to create new products that fit consumer preferences,” John says.

But when an organization invites public input, it should also be prepared to lose its grip on a campaign, as the UK’s National Environment Research Council found out when it created a citizen poll to suggest a title for a ship and ended up seeing the jokey name Boaty McBoatface take the lead in votes.

Encourage endorsements

A consumer merely liking a brand on Facebook isn’t considered all that effective in attracting brand followers, but paying to have branded content displayed in followers’ news feeds does work. Brands should find ways to encourage consumers to recommend companies by sharing why they use their products and services.

“It’s not enough to slap your brand on Facebook and expect things to happen,” John says. “But if you see your friend booked a hotel on Facebook, that kind of endorsement is more likely to be effective than if the person just pressed the like button.”

Understand your customers

Some brands can get away with being political—Ben & Jerry’s uses the political news of the day to further its relationship with consumers. “They’ll launch ice cream flavors tied to political agendas, and it’s believable,” Avery says. “That’s because they’re very focused on their target market and they don’t care if they alienate others.”

Not every brand can get away with political messaging, however. John says a friend who sells artisan maple syrup in Vermont considered an anti-Donald Trump social media campaign during thre presidential election to woo Bernie Sanders supporters. John advised against it. “I said, ‘You’re not a political brand and this feels off-strategy for you,’” John says. The friend followed her advice.

Listen on social and massage your message

Companies can now do quite a bit of listening and data mining on social to get a feel for public sentiment. Nike can track whether people are talking about the company in relation to sweatshops, how expensive its products are, or if they appreciate certain features of its shoes. “This can change your business strategy and how you market,” Gupta says. “The challenge is to find the nugget of insight from this huge amount of data.”

That data can also be used to target customers who matter.

“The benefit of Facebook is that I can use data to identify who might be the right people for the business and do precise targeting of that audience. In TV, I can’t do that,” Gupta says. “When I reach out to my target audience and convey my message, if it’s only to 10,000 people, that might be more effective than reaching 10 million people who mean nothing to me.”

Authenticity wins

Whether a company has garnered millions of Facebook likes or created a hilarious video that has gone viral, marketers are starting to realize that above all, a social media message needs to stay on target—to the intended audience, to the brand’s values, to the social climate--if a company expects to benefit.

Says Gupta: “(Companies) are putting so much money into social media, and they are only just now beginning to learn to stay on message and ask the questions that matter: Does it drive the business, or at a minimum, does it enhance the brand?”

What will we learn about how social media works over the next two decades?

First Published: Oct 03, 2017, 06:39

Subscribe Now