Fixing Indian TV's Audience Measurement Problems

The current spat between NDTV and TAM puts the spotlight on why the television audience measurement system is dangerously flawed. There's a way to sort it out though, provided the entire industry take

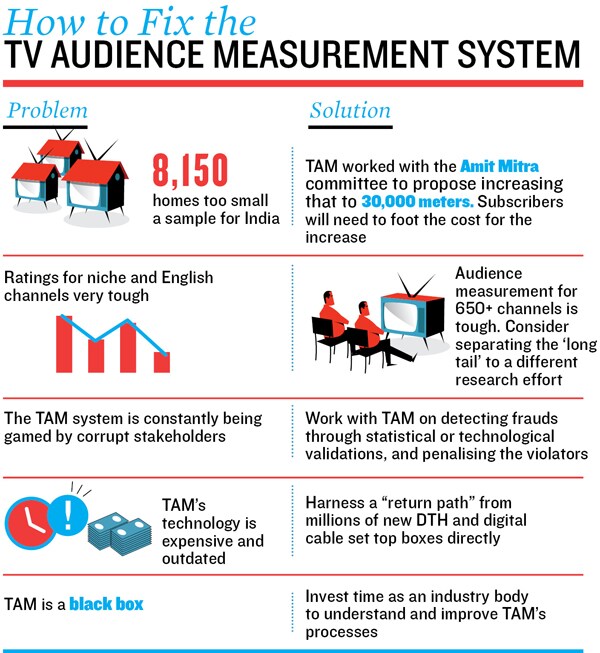

One of the most revealing statements in NDTV’s weighty lawsuit—194 pages targeted at over 30 companies and individuals and between $1 billion and $2 billion in damages—against TV measurement firm TAM and its investors is this: “The primary remedy (of the corrupt activities) was to increase sample size from 8,000 boxes to 30,000 boxes, immediately stopping publication of data until the sample size was increased to appropriate levels.”

“Increasing the sample size to 30,000 would automatically increase their revenue in proportion, so tell me, why would TAM say no to this?” asks Praveen Tripathi, former chairman of the erstwhile Joint Industry Body (JIB) Technical Committee that oversaw TAM and currently CEO of Magic9 Media & Consumer Knowledge, a consumer and media knowledge consulting firm. Tripathi was also the CEO of INTAM, in many ways TAM’s predecessor.

His question exposes the doublespeak that has characterised most of the criticism directed at TAM in recent weeks.

In 2010, the ministry of information and broadcasting, under Union minister Ambika Soni, had constituted a committee chaired by Amit Mitra, the then director-general of FICCI and now the finance minister of West Bengal, to review the existing television rating point (TRP) measurement system. In its report presented in November 2010, the Amit Mitra committee laid down a roadmap for improving the system.

A critical recommendation was increasing the number of Peoplemeters by around 22,000. Funding this increase in TAM’s Peoplemeter homes would entail a one-time capital expenditure of about Rs 330 crore spread over five years, plus an additional operating expenditure of Rs 330 crore a year, according to a senior industry executive. That money will have to come from its current research subscribers.

Most advertisers, save a few large FMCG companies, don’t pay for TAM research in spite of collectively spending Rs 13,000 crore annually on TV ads. They access the data by either getting their media agencies to buy it, or perversely arguing that broadcasters ought to pay for it because it helps them sell ads.

That’s like a pension fund asking private corporations to sponsor research reports about themselves that will then form the basis for its own investments.

Worse, very few have the in-house technical expertise to understand and analyse TAM’s statistical data, much less strategise on it.

Much of the current mess is also tied to the way in which clients choose their media agencies and how their compensation system has evolved. In a majority of cases, the media agency that “bids” the lowest percentage of the advertiser’s annual ad spend as commission—ranging from zero to 2.5 percent—ends up “winning”. At such low margins, they start to eliminate all non-essential costs, like research.

Though they’re forced to subscribe to TAM data by their clients, it’s not really analysed or used in depth. The media agency’s business model relies on making money through unofficial “rebates”, essentially kickbacks from broadcasters as quid pro quo for channelling their client’s ad budgets.

That leaves broadcasters. Even though the top 30 channels garner nearly 80 percent of all viewership, there are another 600-plus, clawing for their share of the Rs 13,000 crore and largely stagnant ad market. Their balance sheets are already stretched and the huge annual “carriage fee” paid to cable operators to ensure their channel’s visibility hasn’t helped either. Given that they already shoulder 70-80 percent of TAM’s research bill and agency “rebates” ranging from 7.5-15 percent, most are in no mood to see their TAM bill go up manifold. With no one, including itself, willing to foot the cost of a nearly four-fold increase in TAM panel size, NDTV lays the blame on TAM’s international owners—Nielsen and Kantar.

“A research agency is not here for charity. It has to be finally funded through subscriber’s contributions,” says Tripathi.

Running Around in Circles

To repeat a cliché, India is arguably the most complex, diverse and geographically large consumer market in the world. For instance, the average viewer spends around 130 minutes per day watching TV. Of this, nearly 80 percent is spent on a leading set of 30 channels. This means that the rest of the channels—anywhere from 150 to 350, depending on the DTH or cable operator—are fighting for a slice of roughly 26 minutes each day.

For instance, the average viewer spends around 130 minutes per day watching TV. Of this, nearly 80 percent is spent on a leading set of 30 channels. This means that the rest of the channels—anywhere from 150 to 350, depending on the DTH or cable operator—are fighting for a slice of roughly 26 minutes each day.

When both the TAM sample sizes and viewership minutes are so insignificant, even minor manipulations in viewing can have a magnified impact on TRP ratings. It is an open secret that the TAM system can be easily gamed by bribing lower-level employees at TAM and households where the meters are placed.

Besides, the Joint Industry Body (JIB) that since 1997 oversaw TAM’s research and frequently questioned its data died an unnatural death around 2004. So, for the last eight years, there has been virtually no industry supervision of TAM. The Broadcast Audience Research Council (BARC), the successor to the JIB, has been a non-starter since 2007 when it was first proposed.

“If people from the industry don’t have time to supervise TAM, they have no right to call it lousy. It’s like a conductor after having fled the orchestra, blaming individual musicians for playing their own tunes,” says Tripathi.

Meanwhile, TAM field staff are often intimidated and threatened by local cable operators (a problem that will become more acute when it goes to semi-urban and rural India) or corrupt channels. Even its CEO, LV Krishnan, regarded as one of the most ethical people in the industry, has received personal threats from powerful people. Much of both the corruption and intimidation can be traced back to the cable operator-local channel-politician nexus.

TAM had even approached the Union government for some kind of official protection for its equipment and staff, to no avail.

“Instead of blaming them, the way for the industry to respond is to knock on LV’s [Krishnan] door, saying here are the resources. Take 10 percent of our manager’s time for next 16 weeks and let’s come up with ideas on how to solve it together,” says Tripathi.

Cleaning Up the Mess

So how do you now solve this mess?

For starters, get BARC off the ground. Model it on the British Broadcaster’s Audience Research Board or BARB. The provider of TV research in the UK, BARB in turn has appointed three different agencies to create the same—Kantar Media (one of TAM India’s parents) for recruiting panel homes and installing meters Ipsos MORI for conducting the survey and RSMB for producing the sample design and conducting quality checks.

Separating ownership of panel meters from research, while taking responsibility for the final data, is a good way for BARC to address many questions around the reliability of TAM’s processes. This is assuming of course that it can progress beyond its five-year standoff between broadcasters and advertisers.

Strengthen TAM’s existing fraud-detection mechanisms and algorithms, while in parallel putting up punitive measures for those who game the system, like disregarding their data for a few months or “naming and shaming” them.

Also, funding the Rs 660-odd crore required to expand TAM’s panel size from 8,150 to 30,000 would appear somewhat less challenging, if BARC were to look at South Africa.

Formed in 1974, the South African Advertising Research Foundation (SAARF) collects a 0.5 percent "levy" on all advertising that takes place, which is then used to fund a comprehensive set of research activities through the year.

Mandating a trivial 1 percent levy (considering that most contracts have hidden "rebates" of 7.5-15 percent anyway) should generate Rs 130 crore annually, no mean sum considering TAM’s current fee income is estimated to be between Rs 40-50 crore.

One could always argue that broadcasters would be wary of being forced to give an additional discount of 1 percent, especially if advertisers refuse to pay the levy.

That’s where the industry would need to come together. And part of it would be to make ad contracts more transparent. Either ban secret "rebates" altogether or force broadcasters to disclose the exact amount they offer as "rebates".

The internet can be a good role model here. For instance, Google and Facebook do not offer advertising rebates anywhere around the world. Google even offers TV ads in the US market run through a real-time and transparent auction system.

Such transparency will shift the focus of media agencies away from volume discounts towards real research and results.

Thanks to advances in technology, it is now possible to improve the quality of TV research, while reducing costs. There are over 37 million DTH subscribers in the country currently, each powered by a relatively modern set top box that is aware of the channel being played. By utilising “return paths” in some boxes and adding them to others using inexpensive plug-in hardware, one could generate viewership data that is orders of magnitude better than today’s. TAM is already understood to be in close conversations with most DTH platforms.

But maybe the most important solution would be for advertisers—the folks who are currently spending Rs 13,000 crore on TV ads and most conspicuous by their relative silence around TAM’s criticism—to sit up and take control.

Disclosure: Forbes India is published by Network18, which also owns CNN-IBN, CNBC-TV18, IBN7, CNBC-Awaaz and other news and entertainment channels.

First Published: Aug 14, 2012, 06:45

Subscribe Now