Women did everything right. Then work got 'greedy'

How America's obsession with long hours has widened the gender gap

Image: Rodrigo Corral/The New York Times[br]

Image: Rodrigo Corral/The New York Times[br]

Daniela Jampel and Matthew Schneid met in college at Cornell, and both later earned law degrees. They both got jobs at big law firms, the kind that reward people who make partner with seven-figure pay packages.

One marriage and 10 years later, she works 21 hours a week as a lawyer for New York City, a job that enables her to spend two days a week at home with their children, ages 5 and 1, and to shuffle her hours if something urgent comes up. He’s a partner at a midsize law firm and works 60-hour weeks — up to 80 if he’s closing a big deal — and is on call nights and weekends. He earns four to six times what she does, depending on the year.

It isn’t the way they’d imagined splitting the breadwinning and the caregiving. But he’s been able to be so financially successful in part because of her flexibility, they said. “I’m here if he needs to work late or go out with clients,” Jampel said. “Snow days are not an issue. I do all the doctor appointments on my days off. Really, the benefit is he doesn’t have to think about it. If he has to work late or on weekends, he’s not like, ‘Oh my gosh, who’s going to watch the children?’ The thought never crosses his mind.”

American women of working age are the most educated ever. Yet it’s the most educated women who face the biggest gender gaps in seniority and pay: At the top of their fields, they represent just 5% of big company chief executives and a quarter of the top 10% of earners in the United States. There are many causes of the gap, like discrimination and a lack of family-friendly policies. But recently, mounting evidence has led economists and sociologists to converge on a major driver — one that ostensibly has nothing to do with gender.

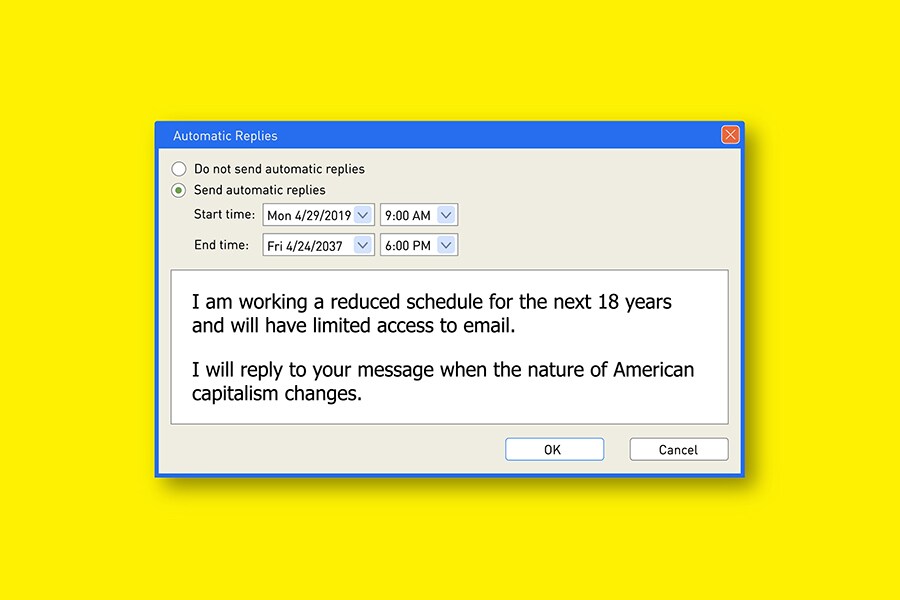

The returns to working long, inflexible hours have greatly increased. This is particularly true in managerial jobs and what social scientists call the greedy professions, like finance, law and consulting — an unintentional side effect of the nation’s embrace of a winner-take-all economy. It’s so powerful, researchers say, that it has canceled the effect of women’s educational gains.

Just as more women earned degrees, the jobs that require those degrees started paying disproportionately more to people with round-the-clock availability. At the same time, more highly educated women began to marry men with similar educations, and to have children. But parents can be on call at work only if someone is on call at home. Usually, that person is the mother.

This is not about educated women opting out of work (they are the least likely to stop working after having children, even if they move to less demanding jobs). It’s about how the nature of work has changed in ways that push couples who have equal career potential to take on unequal roles.

“Because of rising inequality, if you put in the extra hours, if you’re around for the Sunday evening discussion, you’ll get a lot more,” said Claudia Goldin, an economist at Harvard University who is writing a book on the topic. To maximize the family’s income but still keep the children alive, it’s logical for one parent to take an intensive job and the other to take a less demanding one, she said. “It just so happens that in most couples, if there’s a woman and a man, the woman takes the back seat.”

Women don’t step back from work because they have rich husbands, she said. They have rich husbands because they step back from work.

It’s a rarefied problem that many families would love to have — and not all educated couples who face it choose this path. But unpredictable hours also pose challenges for others, including same-sex parents, middle-class families and low earners. Researchers have focused on college-educated women because they’re most prepared to have big careers, yet their careers flatline. Across American life, the people in power making decisions are mostly men.

The same thing is happening in other rich countries. In Japan, despite efforts to encourage more women to work, they are often stuck in limited roles and part-time jobs, largely because men work such long hours, known as “karoshi,” or “death from overwork.” In European countries, with more family-friendly policies, women are likelier to work than they are in the United States — but they’re even less likely to reach senior levels. Daniela Jampel and Matthew Schneid read to their children before bed. They are both lawyers, but he works at least three times as much as she does, and he earns four to six times as much.Image: Gabriela Bhaskar/The New York Times[br]The overwork premium

Daniela Jampel and Matthew Schneid read to their children before bed. They are both lawyers, but he works at least three times as much as she does, and he earns four to six times as much.Image: Gabriela Bhaskar/The New York Times[br]The overwork premium

It’s only in the last two decades that salaried employees have earned more by working long hours. Four decades ago, people who worked at least 50 hours a week were paid 15% less, on an hourly basis, than those who worked traditional full-time schedules. By 2000, though, the wage penalty for overwork became a premium. Today, people who work 50 hours or more earn up to 8% more an hour than similar people working 35 to 49 hours, according to a sociology paper using Current Population Survey data by Youngjoo Cha at Indiana University, Kim Weeden at Cornell University and Mauricio Bucca at the European University Institute.

Overwork is most extreme in managerial jobs and in the greedy professions, a term coined by sociologist Lewis Coser in 1974 to describe institutions that “seek exclusive and undivided loyalty.” (Rose Laub Coser, a sociologist and his wife, also used it to describe the expectations of motherhood). But overwork (or at least time in the office or online, regardless of whether much work is getting done) has become increasingly common in more jobs, whether it’s accounting, information technology or any job in which someone’s manager stays late or sends emails on weekends and expects employees to follow suit.

Technology is one reason for the change, researchers say workers are now more easily reachable and can do more work remotely. Also, business has become more global, so people are working across time zones. A big driver is the widening gap between the highest and lowest earners, and increasingly unstable employment. More jobs requiring advanced degrees are up-or-out — make partner or leave, for example. Even if they aren’t, work has become more competitive, and long hours have become a status symbol.

“The reward to become the winner is a lot higher now than in the past,” Cha said. “You have to stick out among workers, and one way is by your hours.”

For Jampel and Schneid, both 35, two more equal and less time-intensive jobs weren’t an option, they said. For one, they’re hard to find in corporate law: “At the end of the day, these jobs are client service jobs, so if you’re not responding to your clients, someone else might be more responsive to them,” said Schneid, who does commercial real estate law.

Also, they would be leaving money on the table — both now and later, because by putting in long hours now, he’s setting himself up for higher future earnings. If he had a 40-hour-a-week job and she had her current half-time job, they would be working 60 hours a week total — but earning significantly less than he now earns working 60 hours, they said.

“Being willing to work 50% more doesn’t mean you make 50% more, you make like 100% more,” she said. “The trade-off between time and money is not linear. It took a long time to get myself to the point of accepting that.”

There’s no gender gap in the financial rewards for working extra long hours. For the most part, women who work extreme hours get paid as much as men who do. But far fewer women do it, particularly mothers. Twenty percent of fathers now work at least 50 hours a week, and just 6% of mothers do, Cha and Weeden found. There has always been a pay gap between mothers and fathers, but it would be 15% smaller today if the financial returns to long hours hadn’t increased, they found.

“New ways of organizing work reproduce old forms of inequality,” they wrote in another paper.

Men and women with law and business degrees have similar jobs right out of college, other research has found — but a decade later, women earn significantly less. It’s explained by the fact that they work shorter hours and take more breaks. Today, a smaller share of college-educated women in their early 40s are working than a decade ago. Ms. Jampel cooks dinner while Mr. Schneid continues to work after they put their children to bed

Ms. Jampel cooks dinner while Mr. Schneid continues to work after they put their children to bed

Image:Gabriela Bhaskar/The New York Times[br] On call at home

With the rise of college-educated, dual-earner power couples, it was realistic to imagine that two people could both work in jobs at the top of their field and share the duties at home. But at the same time as work became more demanding, family life changed, too.

People are increasingly marrying people with similar educations and career potential — a doctor is likely to be married to another doctor instead of a nurse. Yet the pay gap between husbands and wives is biggest for those with higher education and white-collar jobs. Some parents on elite career paths each continue on them and outsource child care, while others decide not to maximize their family earnings and each take lower-paying, more flexible jobs. But researchers say that because of the changes in work and family, many educated couples are finding that couple equity is out of reach — and many women are left with unused career potential.

“The fundamental problem all along is that someone has to take care of the children,” said Till von Wachter, an economist at the University of California, Los Angeles. “What’s changing here is the assortative mating piece. These women have made all these skills and investments and are not fully reaping those returns.”

It’s affecting more people, because highly educated women are more likely to have children than they recently were. Eighty percent of women in their early 40s with doctorates or professional degrees are mothers, up from 65% two decades ago, according to the Pew Research Center. In 1980, only half of women working in the 10 highest-paying occupations were married, and only a third had a child, found research by Marianne Bertrand, an economist at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. By 2010, they were slightly more likely to be married than other working women, and just as likely to have a child.

Meanwhile, being a parent, particularly a mother, has become more intensive. Working mothers today spend as much time with their children as stay-at-home mothers did in the 1970s. The number of hours that college-educated parents spend with their children has doubled since the early 1980s, and they spend more of that time interacting with them, playing and teaching.

The same challenge affects single parents, same-sex parents and couples in which the father is the primary parent. But in opposite-sex couples, when one career takes priority, it’s generally the man’s.

Men are much more likely to have a spouse who’s on call at home, which enables them to reap the benefits of being on call at work, found a new paper by Jill Yavorsky, a sociologist at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte, and colleagues. Three-quarters of men in the top 1% of earners have an at-home spouse. Just a quarter of women in the top 1% of earners do — and they are likely to be self-employed, suggesting that they have more control over their hours.

A third paper by Cha, using data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation, found that in dual-earner households in which a man worked 60 or more hours, particularly in a professional or managerial job, women were three times as likely to quit. (Men with wives who worked long hours were no more likely to quit.)

Jampel and Schneid had other reasons to split their responsibilities the way they did. She graduated during the Great Recession and was laid off early on. By the time he graduated two years later, he earned more than she did. But gender factored in. Schneid is a hands-on father. He coaches one of his daughter’s sports teams, and tries to come home before the children’s bedtime (he works from home afterward). But Jampel said she always knew she’d do more at home, even if she worked full time: “Women are expected to carry the mental load, and I just took on that responsibility.”

‘Taking the Whole Thing Down’

There are many ideas about how to close the gender gap — things like paid parental leave and anti-bias training. Women could negotiate more men could do more housework. But most are band-aids, Goldin said — they probably help, but they don’t address the deeper problem, and leave individual families to figure out their own compromises.

“It’s this system we put in place in the era of ‘Mad Men’ and we’re stuck with, and we’re sort of hammering away at in small ways rather than taking the whole thing down,” she said.

Certain changes would lighten parents’ demands at home, like universal public preschool, longer school days, free after school care and shorter school breaks. But the ultimate solution, researchers say, is not to make it possible for mothers to work crazy hours, too. It’s to reorganize work so that nobody has to.

The most effective way to do that, Goldin’s research has found, is for employers to give workers more predictable hours and flexibility on where and when work gets done. One way that happens is when it becomes easier for workers to substitute for one another.

Conventional wisdom, especially in the greedy occupations, is that this is impossible — certain people are too valuable and need to be available to clients anytime. But some professions have successfully challenged that notion.

Obstetricians, for instance, used to be on call when patients went into labor. Now it’s much more common for them to work eight-hour shifts in a hospital — and many more women do the job. At an elite global consulting firm, one team gave everyone one weeknight off, no calls or emails allowed — and realized that working late nights might not be necessary after all.

“It’s hard to get people to change because they take so much for granted that this is the way it has to be,” said Leslie Perlow, author of “Sleeping With Your Smartphone: How to Break the 24/7 Habit and Change the Way You Work” and a Harvard Business School dean and professor. “But this is really a system problem. People don’t recognize how being always on is creating this pressure to be always on.”

The change is unlikely to happen, researchers say, unless workers start to demand it. Companies benefit from always-on workers they won’t change just to be humane. They have to risk losing valuable employees if they don’t — including men. When women are the only ones who switch to jobs with predictable hours or take advantage of flexibility, it just hurts their careers more.

There are signs that things could change. Younger men say they want more equal partnerships and more involvement in family life, research shows. Women are outperforming men in school, but employers are losing out on their talents. And people increasingly say they are fed up with working so much.

“It may mean rearranging jobs, but you’d think there’d be a lot of money in it,” said Nicholas Bloom, an economist at Stanford University who studies companies’ management practices. “Firms have enormous incentive to really design jobs so they can access these highly educated people who want to work 40 hours a week and not 80.”

The arrangements that the Schneid-Jampel family settled on are the best they could have hoped for, given the way things are, they said. But he feels overstretched between relentless pressure at work and time away from his family.

“I think I’d be happier in life if I was home more with my children and if I didn’t have the same stress at work,” he said, “but I think this was the best decision for our family.”

Jampel feels angry that the time she spends caregiving isn’t valued the way paid work is. “No one explains this to you when you’re 21, but in retrospect, it was not a smart decision” to go into debt for law school, she said.

She said she feels lucky that she’s found substantive, interesting part-time work. He feels lucky that he found a firm that doesn’t require him to do all his hours at the office. But if they could rewrite their lives? They wish they could have had better options.

First Published: May 07, 2019, 11:34

Subscribe Now