Various versions of English, nay, Inglish

No country, not even England, can appropriate English as its own. Not when the world has decided to adopt different versions of it, either through technological or cultural customisation. In India, it

Words have a way of waking your mind. Funny words, especially rude ones, make children explode, and the child trapped in the adult giggles aloud. Last summer, lulled nearly to sleep by the sun on our outdoor swing, (heavily weighed down by a non-alcoholic beer in my hand and a big baby in my belly), I was smiling at the wonderful words spun by Henry James, who wrote his last novel, The Golden Bowl, not far from where I now live.

Suddenly, I am attacked by an unfamiliar word.

“Bumfuzzle! Bum, Bum…”

Our three-year-old daughter streaks past, splashing into the paddling pool shrieking “bumfuzzle!” I nearly leap, spilling pale stinking bubbles down my big bump. I am lost for words quite, in fact, bumfuzzled, but I don’t know it yet. Befuddled? It sounds onomatopoeic and, appropriately, it means to be confused.

When we listen to words, they often will reveal their meaning to us. But “bumfuzzle” had me flummoxed. Later, as I explained my messy appearance to my husband, he laughed and showed me a television advertisement for British telecom company Three UK’s Singing Dictionary campaign, which had probably got in my daughter’s head. It showed a well-dressed, conservatively-collared and white liveried choir, singing aloud the word “BUMFUZZZZZLE” in earnest. It was brilliant. It woke my mind to the lengths language has travelled in several hundred years.

We lose and gain language daily. We invent text-speak, we make up words. We change usage according to predictive text.

It may not work for those who want to master the Queen’s speak for gravitas. But does she even own it anymore? Gravitas, in fact, may be gained by grasping the new frontiers in language, using ‘wicked’ in its street sense to mean ‘fantastic’. This, of course, would have bumfuzzled poor L Frank Baum, writer of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, who meant wicked in its medieval sense when he whittled on about the wicked witch of the West.

But language isn’t just the preserve of lexicographers or dictionary compilers anymore. Neither is it the realm of linguists and scholars. It belongs to all who use it. Marlon James, the first Jamaica-born recipient of the 2015 Man Booker Prize announced last month, drove home the point about diversity in the language as used globally today. Professor Michael Wood, chair of the judging panel for the 2015 prize, in his introductory speech spoke of this with pride. English is evolving everywhere. Even the most prestigious of literary prizes has dropped its guard, welcoming outside influences to the language.

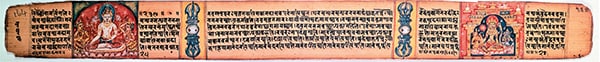

Looking at the spanning branches of the language tree, we see where Sanskrit and English diversify. But they are, in fact, rooted together. When he was an amateur language scholar and a deeply devoted student of India studies, Sir William Jones (co-founder of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, January 1784) hunted for the means to expose the links between these languages when he arrived in Calcutta (now Kolkata) as a Supreme Court judge in 1783. He chanced upon the Ramayana and the Mahabharata and announced to the world that he had ‘discovered’ the equivalent of The Iliad and The Odyssey, which were held by the Romantics and Early Victorians as foreshadowing all literary progress. In the 1780s, Jones upheld the ancient, as yet untranslated, Sanskrit texts as finer in composition and relevance than anything the world had seen (John Keay, India Discovered). Jones went on to teach himself Sanskrit to promote his fortuitous discovery of these yet-unknown, unheard of treasures.As Jones discovered and attempted to point out, father in English, vater in German, pater in Latin and Greek, fadir in Old Norse and pitr in ancient Vedic Sanskrit resonate with each other implicitly. And it is through the strong offices of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, set up by him, that the study of language in India, and its meandering modernity, continued.

In the midst of the geographical discovery phase of world history (1200-1400 CE), it became clear that to embrace other cultures for purposes of trade (or any other intent), language would have to be used.

And so we experience the clash of cultures. In India, in particular, we have had since the 1600s a unique melding of trading terms entering our languages from other countries. Our Hindi word for orange, narangi, comes from naranja, the Spanish equivalent, because oranges travelled to the sub-continent from the Mediterranean. Our unique system of numbers, including the zero, was introduced to the world by the widely travelled Arab traders, using the ancient Sanskritic numbers. The world still calls the European or English written number system Arabic, recently updated to include Hindi, so Arabic-Indic/Hindi.

What is transpiring is an amalgamation of cultures. Today, we rarely look for origins of words, so busy are we making up new ones. In the late Victorian period, a number of scholars concerned themselves with compiling this amalgamation. The Victorian era was in many ways the height for lexicographical projects. Two of the grandest were compiled, interestingly in correspondence with each other: Hobson-Jobson and the New English Dictionary (NED), subsequently recast as the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). This grandest of all dictionaries, which most of the English-speaking world sets its store by, has at its very core a set of words of Indian origin demarcating a culturally relevant linguistic process.

India has recast British culture through her use of language. For example, Satan, the great devil, from shaitan. So today, when the Official Scrabble Words (OSW) finally incorporates several words of Indian origin into the officially allowed words for players to have a better score in their arsenal, we ought to recall that Indian words have crept in, with cultural relevances being noted, into the OED through the via-media of the much lesser known Hobson-Jobson.

Salman Rushdie refers to Hobson-Jobson as ‘the legendary dictionary of British India’, (Imaginary Homelands, 1992, page 81). The Hanklyn-Janklyn (Nigel Hankin, 1997) is the only other such lexicon of Indian-English terminology in existence. It classifies itself as “A Rumble-Tumble Guide to Some Words, Customs and Quiddities”. A more recent paperback edition appeared nearly a decade ago on February 17, 2008, and is certainly worth a dekho or dekko, pronounced deco by most English speakers across Great Britain.

It may seem peculiar to someone who has not lived in London, or spent time in the UK, that not everyone uses the Queen’s English in England, let alone the other subjuncts of the kingdom. Professor Henry Higgins (played by Rex Harrison) sang eloquently about this in the 1950s adaptation of Shaw’s Pygmalion, the wonderfully musical My Fair Lady.

An Englishman’s way of speaking absolutely classifies him.

The moment he talks he makes some other Englishman despise him.

One common language I’m afraid we’ll never get.

Oh, why can’t the English learn to set a good example to people whose English is painful to your ears?

The Scotch and the Irish leave you close to tears.

There even are places where English completely disappears. In America, they haven’t used it for years!

If only Higgins had asked Colonel Hugh Pickering (essayed by Robert Coote), a fellow phoneticist, who in the film has just returned from India, about the state of the English language there. He would have assured Higgins that it is alive and evolving, faring far better than in America. They could have added a whole new verse to the song about Wren & Martin grammar usage. Then the song would have ended differently. Maybe like this:

Now take the case in India, Where we should have no fears.

Why, from Calcutta to Bombay, They’ve been using it for years.

They’ve even invented new words

And multiplied it two thirds. In fact in India English consistently reappears.

The fictional Colonel Pickering discovered in excess of 200 distinct languages, apart from dialects. It is worth mentioning here that a more expansive list, including the 22 ‘scheduled’ languages, stands at 461 spoken languages, including 14 considered extinct across the subcontinent today (www.ethnologue.com ). But no language map acknowledges the predominance of English as a common link. We even write Hindi in English letters so that more of the population will understand it. The letters of the English language go further in the subcontinent, even with non-English readers. In Fry’s Planet Word on BBC, Stephen Fry (right) found that children lose the ability to enunciate certain sounds meaningfully by the age of five

In Fry’s Planet Word on BBC, Stephen Fry (right) found that children lose the ability to enunciate certain sounds meaningfully by the age of five

In a documentary series (Fry’s Planet Word, 2011) on the BBC, Stephen Fry found that children lose the ability to enunciate certain sounds meaningfully by the age of five. If you weren’t born into a Hindi-speaking ethos, to say Bumbai is tough.

So the British administrators, for their own convenience, went about applying anglicised names for most places. Ooty, in the Nilgiri hills of Tamil Nadu, is an apt example. Its tongue-twisting Tamil name is Udhagamandalam the British surveyors called it Ootacamund, which today we still call Ooty lovingly. Mumbai became Bumbai became Bombay, or vice versa. Kolkata became Kulkutta became Calcutta. This process rubbed along, at times with discomfort, but it made places far-flung and out of familiar speech patterns easier on the tongue.

I start to imagine this language as with a life of its own. Appropriately, at this point, my now four-year-old daughter runs past me still shouting “Bumfuzzle! Bum, Bum…”! She knows how it amuses me. I am proud of her confident use of Hindi words in the midst of English sentences. Even if she is cheekily asking, in her fast-becoming-posh-southeast England accent, for a ‘glass of paani please…’

Inglish, it seems, is by no means limited to India.

The author is an academic and filmmaker with a curiosity about how language lives. Her second novel, 100 Percent Perfectly Okay, written in Indian-English, is set for release next year

First Published: Dec 15, 2015, 06:09

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Sep 10, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)