India's Primary Health Care Needs Quick Reform

Primary health care delivery needs to reinvent itself. Only then can India aimfor universal health coverage

Early last year, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh announced the government would work towards providing Universal Health Coverage (UHC) for all. As intents go, it is as noble as it gets. This, because the operative word here is ‘universal’. Much like the Indian Constitution promises every citizen justice, liberty, equality and fraternity, the PM proposed health care be added, as a “fundamental right”, whether you’re above the poverty line or below it.

Soon after the announcement, at a high level ministerial meeting in Delhi almost every minister pledged to work together. In the months that followed, two ambitious programmes were announced: National Urban Health Mission (NUHM) and Free Essential Medicines. When implemented, it would cost the country Rs 22,000 crore and Rs 28,560 crore, respectively. But the agreement had irony written all over it.

On December 27 last year, representatives of various states fought fiercely over how the proposed food security bill ought to be financed. But when it came to the UHC, there seemed near consensus. For various reasons though, the idea didn’t take off.

As things stand now, funding for the National Urban Health Mission and Free Essential Medicines have been deferred. Finance Minister P Chidambaram’s latest proposals mention one of them in passing. “It’s a bit of a disaster… with two years of the Plan over, there’s not much one can do towards the UHC in the remaining three years,” says AK Shiva Kumar, a welfare economist from Harvard and convener of Kolkata Group, and advisor to the Sonia Gandhi-led National Advisory Council (NAC) on universal health financing. Bureaucrats in Delhi are ambivalent too. While slow economic growth may come across as a plausible reason, truth is, nobody seems to be in charge.

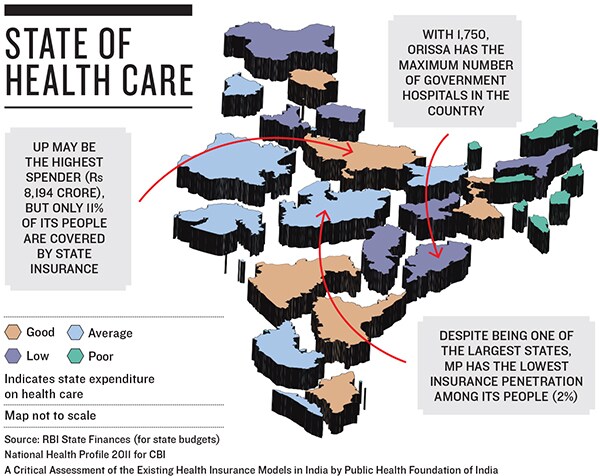

As for the states, while providing health care is their responsibility, by all indications, they aren’t prepared. “Which state has projected its requirements for the medium term or has prepared any plan? There may be many states that don’t even know about the UHC,” says M Govind Rao, director of the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy and a member of the 13th Finance Commission. Instead, he discovered, states are using money from the Centre to cut spending on health care, instead of using these funds to augment it.

On its part, the Central government has always acted unilaterally and rarely consulted states on national health schemes, points out Priya Balasubramaniam, study director of the UHC. The Rural Health Mission, for instance, was delivered in a top-down manner.

Caught in this crossfire are initiatives that could drift so far apart that pulling all of them back into a single framework—the UHC—will be a challenge. Making matters worse is that there is little evidence to indicate that political or administrative will exists to integrate essential (primary), general (secondary) and specialised (tertiary) health care services under one umbrella.

Who bells the cat?

Prathap Reddy, chairman, Apollo Group of Hospitals, has a question. “To what extent can the government absorb health care costs?” The answer, he says, lies in first addressing the basics, or primary health care (PHC). “Clean drinking water alone can help eliminate gastric ailments that afflict 200 million people.” (See package ‘Why We Need to Challenge Old Thinking…’ on page 78.)

The problem here isn’t a lack of funds. In fact, nearly three-fourths of the country’s health budget goes into addressing PHC through the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM). The country spent close to Rs 21,000 crore in 2012-13 alone.

Where it has been used wisely, things have worked. Take Bihar. Infant mortality rates there used to be among the highest in the country. Today, it is on par with the national average. “This mission has shown what a little boost to public health spending can do,” says Amarjeet Sinha, former health secretary, Bihar. But if you leave out states like Bihar, Assam and Rajasthan, most of the others are a black hole.

In a first ever estimate on the quality of primary care in the country, World Bank economist Jishnu Das and his colleagues studied rural Madhya Pradesh and urban Delhi. In 63 percent of the cases they looked at, treatment provided in public clinics was provided by insufficiently trained personnel. To drive the point home, Dr Naresh Trehan, chairman and managing director of Medanta, points to the Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA), or community health workers in the country. “There are 800,000 of them at the village level. But they’re trained badly. We need to ask how can we upskill them? How can we make them our frontline workers who identify early signs of a disease?”

To achieve that, PHC delivery needs to reinvent itself. There are creative solutions on offer. Gautam Sen, chairman of Healthspring, a general practice (GP) chain in Mumbai, has proven that in Radhanagari, Maharashtra. With financial assistance from Hindalco, Dr Sen runs a primary care centre that caters to 150,000 people and costs the company just Rs 12 lakh each year. He trains his own staff.

As against this, the Central government spends on average Rs 3 crore to run a single centre in most states. In Radhanagari, Dr Sen says, the government has everything going: Two rural hospitals and seven primary centres. But these centres have no doctors to man them or medicines to distribute. Unsurprisingly, villagers have given Dr Sen 10 acres of land where he plans to build a fee-for-service hospital.

Nachiket Mor, a former ICICI bank veteran and now a member of the expert group on health care, believes these are the kind of gate keepers every state needs. That, he believes, will ensure 95 percent of patients are taken care of at the primary level. In turn, this will take the stress off insurance schemes, make them viable, and offer them the latitude to focus on high-cost tertiary care.

Misplaced priorities

How many people know of the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY)? The programme has enrolled 120 million people so far. Many state governments have started their own insurance schemes named Arogyasri (prefacing it with ‘Rajiv’ or ‘Vajpayee’, depending upon their political party), Kalaingar, Cheeranjeevi and whatever else in their reckoning will go down well. These schemes are meant to pay for high-end hospitalisation, easy to execute and cultivate vote banks.

But here’s the problem: The insurance claim ratio is said to be rising at 30-50 percent which, some may argue, is a sign of success. But then, so are the costs. In the RSBY, average claims have moved up from Rs 750 per household per annum to between Rs 1,100 to Rs 1,200. Ironically again, the money isn’t going into improving health care, but in purchasing it.

In Andhra Pradesh, where Arogyasri originated and covers 85 percent of the population, a big opportunity was lost by not using this money to improve the public health system, says Dr GN Rao, founder chairman of LV Prasad Eye Institute in Hyderabad.

“Many government-funded schemes are well-intentioned in terms of providing secondary and tertiary care,” says Dr Srinath Reddy, chairman of the expert group. “However, these schemes do not provide continuity of care because they neglect primary care.” If that happens, both Dr Reddy and Nachiket Mor fear schemes like these will induce demand for more expensive health care services, consume larger portions of the budget, and eventually drive health insurance premiums through the roof. This is the problem the US is grappling with.

That is not to say insurance and a UHC plan are mutually exclusive. Before demitting office in February, Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority (IRDA) chairman Hari Narayan strongly advocated expanding RSBY across the country to include people above the poverty line as well.

But if you do that, argues Mor, policy makers will have to integrate primary health care and secondary health care. In doing that, the per capita expenditure will shoot up to Rs 2,000 from the existing Rs 750. That’s the kind of money nobody has.

Show me the money

For every rupee you spend, Rs 0.70 goes in buying drugs. It’s a dragon that raises its head all too often. To slay it, many countries provide essential medicines free. Brazil, for instance, provides diabetes and hypertension drugs free even through private pharmacies.

Taking a leaf out of that book, last year the Central government said it would set aside Rs 28,560 crore over five years to provide essential medicines free and cover 57 percent of the population. But the latest budget barely finds any mention for a provision of this kind. What exists instead is a nominal increase in outlay by Rs 457 crore.

Assuming the idea is implemented ruthlessly and it offers financial protection to a few million people, would the problems with tertiary health care go away? The answers, once again, lie on the ground.

R Poornalingam, former managing director of Tamil Nadu Medical Services Corporation (TNMSC), set up the country’s first technology-driven drug procurement and distribution system for the state. An advisor at the World Bank now, he noticed something rather ridiculous on a recent visit to Jharkhand. “Rs 100 crore worth of drugs were procured. But the health secretary did not know what to do with drugs worth Rs 35 crore. There was no demand.” When he was in Chhattisgarh, he found suction equipment worth Rs 150 crore being dumped in toilets.

In Karnataka, a Comptroller Auditor General (CAG) report published last month showed drugs were procured in excess of what was needed and stored in toilets, kitchens, and ambulance sheds.

Some states like Rajasthan though have reformed their systems and expanded procurement—even for expensive cancer and cardiac drugs—so much so that people from neighbouring states are queuing up, says Samit Sharma, managing director of Rajasthan Medicine Services Corporation.

To implement this on a larger scale, the Centre will have to provide the leadership, says Poornalingam. The states, he is convinced, will not emulate each other. That is why he is a fierce advocate of a Central Procurement Agency for national schemes. To manage this, there are health management technologies available from other parts of the world. By way of an example, Sujay Shetty of consulting firm PwC offers the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence in the UK. Else, most states will remain clueless and go about doing all of the wrong things, he warns.

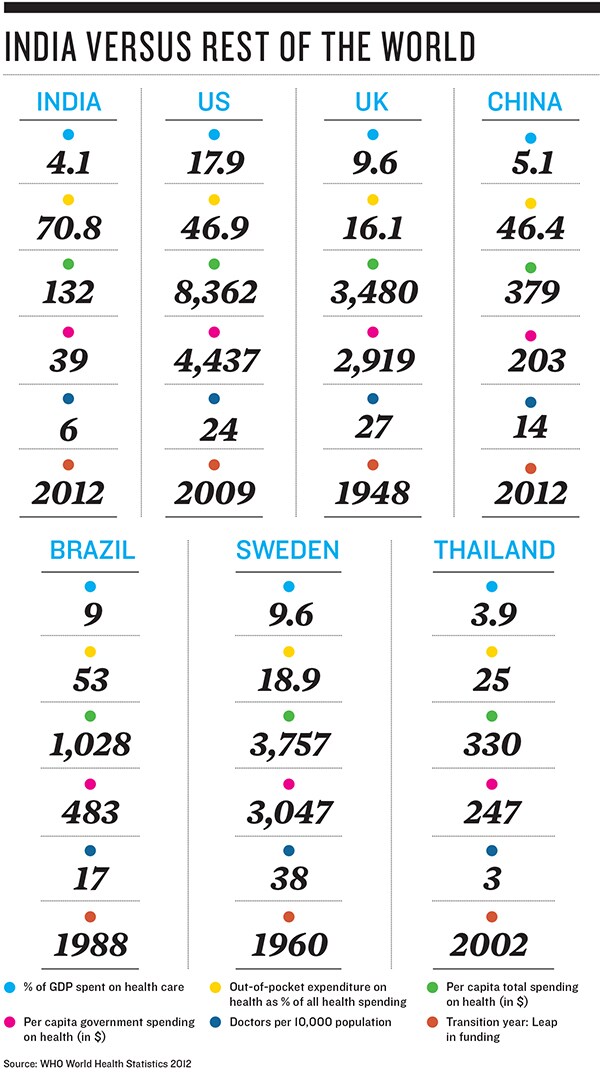

In Tamil Nadu for instance, people have been exposed to so much Amoxicillin, that many of them are now resistant to this antibiotic. In other parts of India as well, similar cases of immunity to antibiotics are mounting. Experts like him fear if free medicines are clubbed with schemes like the NRHM, problems like these are inevitable.What all of this boils down to is that if all three—primary, secondary, and tertiary health care—were bundled into a single package, the math tots up to a per capita expenditure of at least Rs 1,500. All put together, it will consume anywhere between 3.5 to 3.8 percent of India’s gross domestic product (GDP).

India’ GDP is now close to $2 trillion. Three-and-a-half percent of that to provide UHC on all three fronts is a lot of money. And that brings us back to the question Prathap Reddy posed at the outset. Where does this money come from?

By the looks of it, the government doesn’t quite have the spunk in it to raise taxes to fund an UHC programme. And the voters aren’t asking for it. International experience suggests they will when their per capita income touches $5,000. Indians now have a per capita income of $3,851.

“Health care is still not high on the election agenda. But it is getting there. That is why you hear all these noises [about UHC and National Urban Health Mission],” says Naresh Trehan. “The elephant is in the room. Elections are not fought on health care issues. Politicians will not commit this kind of money for at least another decade,” points out Nachiket Mor.

Private providers—from Fortis’ Shivinder Singh to Trehan—seem keen. But consensuses around the basic principles are still elusive. “Many of these meetings I go for turn out to be a verbal duel between government and private sectors. We both want affordability, access, and quality. Nothing can be solved in five years,” says Ashwin Naik, founder and chief executive of Vaatsalya Healthcare, a chain of hospitals in Tier II and III towns. The hope is, once rules are in place, with treatment protocols and rationalisation of cost and fee structure, which a NAC committee will bring out in a month, the needless battle will stop and the conversations towards a solution will begin.

Among politicians, only a few get the idea of universal care. “It will eventually come. I no longer get calls from MLAs for transfers and postings, but for doctors, 108 [ambulance] services, converting primary health care centres in their constituencies into 24/7 service,” says Karnataka health secretary Madan Gopal.

Back in the 1970s, eye care advocacy groups convinced then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi to include eye care in her 20-Point programme. Thanks to that, says Dr GN Rao, anyone with an eye problem today is assured of treatment, whether he can pay or not.

“We need similar commitment to UHC. Maybe a health czar sitting in Delhi should drive it.”

First Published: Mar 19, 2013, 06:04

Subscribe Now