Star won the broadcast and digital rights for the IPL-or did it?

I&B ministry wants Star to share the pie with Doordarshan

Image: Mark Brake / Getty Images

When Star India in September 2017 won the global broadcast and digital rights for the Indian Premier League (IPL) with a whopping $2.55 billion bid, the company assumed it had hit a cricket century.

However, while gaining the world’s richest domestic Twenty20 competition, the Rupert Murdoch-owned company has been under fire from various quarters, including billionaire Subhash Chandra and India’s broadcast ministry. They either want a piece of Star’s pie or for it to lose the rights altogether. At stake is a key chunk of India’s $20 billion media and entertainment business.

Star’s potentially biggest threat comes from the country’s broadcast minister Smriti Irani, a popular TV actor-turned-politician who became a household name through several shows on Star before the company pulled the plug on them.

Irani’s ministry proposed late last year that the IPL, whose viewership has been rising, be declared a “sport of national importance”. Under the law, that would require Star to share the uninterrupted live feed of the IPL with the national TV service Doordarshan or DD. (DD, unlike the channels of private companies like Star that viewers have to pay for, is free.) The idea is that if there’s a sport of national relevance then it should reach as many viewers as possible, and the national broadcaster has the widest reach.

The ministry’s must-share list currently includes the Olympics, Asian Games, all official one-day cricket where India is playing and the men’s and women’s singles Grand Slam finals. The list is reviewed sporadically, and the last time, in January 2017, the IPL was not on it. Live feed apart, the law stipulates that the broadcaster will also have to hand over at least 25 percent of the ad revenue to the government. For cash- and content-starved DD, this would be a quick fix.

The proposed move has rattled business sentiment. Critics say it clashes with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s stance since coming to power in 2014—that he wants to make India an easier country to do business in. “This proposal is almost like a private business turning public [state-owned],” says Girish Menon, partner at consultancy KPMG. “The ability to plan your business gets affected because of government intervention—and how do you compensate an investor for that? It’s inconsistent and unfair to existing rights owners.”

Adds another global-consulting analyst who declined to be named, “This is a private league. It’s people playing cricket against each other in a stadium. How does that become of national importance? And how has it not been of national importance for the past ten years of its existence? You can’t judge national importance just because the viewership has increased.” (Ministry officials did not respond to several requests for comment.)

Last year, Sony Pictures Networks India (which had the broadcast rights for IPL’s initial decade until it lost them to Star in September) raked in a reported $200 million in ad revenue for the 59 matches that were played between April 5 and May 21, roughly $9,000 for a ten-second spot buy (title sponsors paid close to that per second).

Sony beamed the matches across six channels to 411 million people, according to data by the Broadcast Audience Research Council, up by 10 percent from the previous year. KPMG’s Menon says: “Cricket rights are extremely valuable. They ensure subscription revenues as sports channels are priced pretty high and every cable operator will have to offer them, and they bring in massive revenues from advertisers.”

It’s not clear the ministry’s proposal will go through, but if it does, Star could lose out on at least $500 million in subscriptions, a person familiar with the company’s concerns told Forbes Asia. That’s assuming a leakage of just 10 percent of viewers to DD. “Everyone is talking about the loss of ad revenue, but the bigger hit will be to subscription,” this person said. “Because if you can watch it for free on DD, why will anyone pay for a Star Sports channel? The damage this can cause is huge.” Star itself did not offer comment. (Unrelatedly, the company is to be part of an announced sale of Murdoch’s 20th Century Fox assets to Walt Disney Co.)

The pressure is high as the IPL season is around the corner.

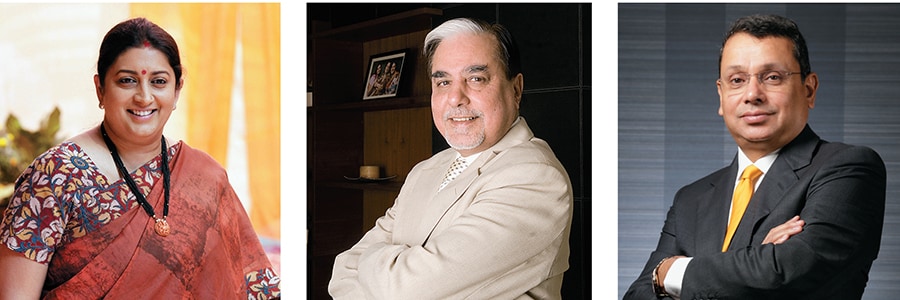

Even before the government bazooka, Star was trying to put out fires ignited by one of its fiercest competitors, Zee Entertainment Enterprises, whose owner Chandra is also a member of India’s upper house of Parliament.  Broadcast minister Smriti Irani (extreme left) and billionaire Subhash Chandra (centre) are at odds with Asia president at 21st Century Fox (which owns Star), Uday Shankar

Broadcast minister Smriti Irani (extreme left) and billionaire Subhash Chandra (centre) are at odds with Asia president at 21st Century Fox (which owns Star), Uday Shankar

Image: Smriti Irani: Raj K Raj / Hindustan Times / via Getty Images Subhash Chandra: Ramesh Pathania / Mint via Getty Images Uday Shankar Joshua Navalkar

Days before the winning bid for the IPL was announced, Chandra’s younger brother Jawahar Goel, who runs Dish TV, the group’s direct-to-home distribution business, wrote to a slew of officials, including broadcast minister Irani, the head of the Board of Control for Cricket in India or the BCCI and the competition watchdog. He warned that were Star to win the telecast rights, it would create an “absolute monopoly” and that “such a situation would not only be anti-competitive but anti-consumers as well”.

Although Dish TV’s parent Zee had not bid to broadcast the IPL, the company has a bitter history with the sport that might explain its efforts to torpedo Star’s bid.

In 2000, NewsCorp (also Murdoch) won the rights to broadcast the cricket World Cup over Zee’s higher bid. In 2005, ESPN Star Sports won the broadcast rights for Test cricket, once again despite Zee’s higher bid. The matter ended in the country’s top court, where Zee lost. In 2006, Zee won the rights to broadcast international tournaments when India played in neutral venues (known as the neutral venue rights).

In 2007, the year before the first IPL season, Zee launched the private India Cricket League (ICL). The idea was similar to the IPL, and the matches were played in the Twenty20 format. Soon after the launch of the ICL, the BCCI cancelled Zee’s contract for the neutral venue rights. (A court case on that drags on.)

The ICL would’ve done the same thing for Zee that IPL did for Sony and that it will now do for Star—provide lucrative sports programming. But the BCCI refused to recognise ICL and reportedly threatened to ban players who joined the ICL. In 2008 BCCI launched the first season of the IPL, which put a nail in ICL’s coffin, and it folded by 2009.

With little hope of getting back into a cricket play, Zee eventually sold its sports broadcast business to Sony in 2017. With Zee no longer having skin in the game, Goel’s letter could be seen as simply creating trouble for its competitor.

On a recent day in his office in the satellite city of Noida, a 7-foot-tall, modern take on the Indian god Krishna in one corner, Goel narrates Zee’s woes and disputes notions of creating trouble for Star for cheap satisfaction. “The duty to regulate is for these people [to whom he sent the letter]. I have raised the issue before them, tabled it, written it. Now it is for them to take the call. If the next stage is for me to go and fight this in a court of law, this letter will help,” he says.

For Star, cricket is vital not just to increase its TV subscribers, but also to deepen its presence in the next frontier for broadcasters—digital—via its streaming app, Hotstar. It has advertising, but the idea is to get paid for premium content there also. “The biggest viewership [after movies] happens around sports. And at this point it doesn’t get more premium than IPL,” says KPMG’s Menon.

IPL, says Ashish Bhasin, South Asia chairman of media firm Dentsu Aegis Network, has transformed cricket from a sport that was watched by men to one that is now watched by families, including women. (Last year 41 percent of the viewers were female.) “IPL is the foremost event in the whole year’s ad calendar,” Bhasin says.

With digital advertising projected to increase by about 31 percent annually to $4.5 billion by 2021, Star was not the only one vying for IPL’s digital streaming rights. Also bidding were Facebook and telecom providers Reliance Jio Infocomm and Airtel. [Reliance is the owner of Network 18, the publisher of Forbes India.]

Irani and Uday Shankar, now the Asia president for Star’s parent Fox, have crossed paths in the past, well before the current feed-sharing controversy. At the time, Irani was acting in a range of soap operas on Star, nearly all of which had been made by producer Ekta Kapoor. It was Shankar who cancelled Kapoor’s shows—and Irani’s platform— citing poor ratings. This time around Irani wields more power.

For now, Shankar is doing the rounds of the capital, meeting officials at DD in an attempt to find alternatives to fill its bare hours.

First Published: Mar 20, 2018, 15:04

Subscribe Now