ACE: Riding high with India's infrastructure story

Action Construction Equipment has been a key beneficiary of the country's rapid infrastructure buildout

By 1995, Vijay Agarwal had spent over a decade working for Escorts. By his own admission, he felt “stifled" within the company. Escorts had not gone anywhere for a while and its employees were just doing the same thing day in and out. Agarwal wanted an exit ramp and worked on getting out quickly.

On a small plot on Delhi"s outskirts, Agarwal, who had studied at the prestigious Faculty of Management Studies at Delhi University, pooled in ₹15 lakh from his savings and got to work doing what he knew best—making cranes and looking for customers. He named his company Action Construction Equipment (ACE) after an earlier name didn’t pass muster with the registration authorities. He also learnt first-hand about the challenges of running a business.

Cranes were leased by operators who then rented them out on a daily or monthly basis. They’d only buy from a new company if they were able to finance them and make money while renting them out. The return on investment had to work in their favour. This meant Agarwal had to work not just on making cranes but also on getting them financed. He tied up with SREI and Magma Fincorp to get his customers financing. Initially, business was slow, but as customers saw the value proposition, he started getting his first orders.

The first crane rolled out in March 1996 and the business had a slow start in 1997 with sales of 25 cranes. Still, Agarwal says it was a better product at a cheaper price and it managed to get his former employers riled up. They did everything to shut him down, including suing him for product infringements, in lower courts in places far away from Delhi—Ranchi, Jamshedpur and Kolkata. It took several years, but ACE eventually prevailed. Agarwal says he never wavered in his belief that he could make a product that was better than that of his Indian and multinational rivals.

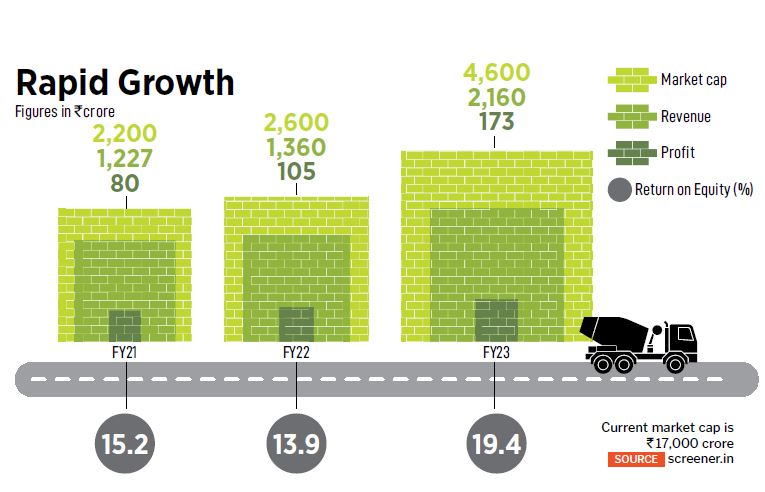

Almost three decades on, it is clear that the 76-year-old founder has passed this test with flying colours and is likely to be a key beneficiary of increased spending on infrastructure and manufacturing. ACE is now a ₹17,000-crore company (by market capitalisation) and a market leader in pick-and-carry cranes and tower cranes in India. It also makes construction and agricultural equipment. With growth taking off in the last three years, it plans to get aggressive on exports that make up 9 percent of its ₹2,700 crore revenue. The business is debt-free and generates enough cash for expansion without leveraging. “Our base case is that the business should be three times as large in the next five years," says Sorab Agarwal, executive director at ACE.

To understand the vast sums being spent on roads, bridges and tunnels across the country, one needn’t step out of Mumbai. Across its western shoreline, the outline of a vast new project is taking place. Its 29.2 km long, eight-lane coastal road, when built, is expected to be used by 130,000 vehicles a day. Across its length and breadth, excavators dig, boring machines work on tunnelling and road contractors lay concrete.

Projects like these have been a boon for ACE as has infrastructure spending, which was increased by 11 percent in the interim Budget 2024 to ₹11.11 lakh crore. There is also the increased activity on factory floors where ACE supplied forklifts.

The company’s history provides an insight into the ebbs and flows of India’s investment cycle. In its initial years, ACE was focussed on getting orders and establishing itself as a brand. Agarwal was clear that quality would make or break the company. To this end, he visited industrial fairs in Italy and Germany to get clues on the design of products overseas and come back to India with the intention to reverse engineer. The efforts were successful if viewed from the prism of the cases that Escorts filed against the company. When ACE started making backhoe loaders, a staple of multinational JCB, it too sued the company for infringement. ACE won those cases as well.

In 2003, a little under a decade after setting shop, ACE received a large order from Reliance Industries (owner of Network18, the publisher of Forbes India) when it was setting up its Jamnagar refinery. RIL needed a large number of cranes and its original suppliers’ order books were full. It turned to ACE and gave it a 50-crane order. It helped take the brand national. Suddenly contractors nationwide knew about the company.

That was also the time of India’s infrastructure build-out under the Vajpayee government and projects like the Golden Quadrilateral highway network propelled demand. “The company had a good run during this period and our revenue growth between 2002 and 2008 was 68 percent a year," says Sorab. In 2006, ACE tapped the public markets as Agarwal believed customers had more confidence in a listed entity.

It was at the peak of the first infrastructure cycle that the company expanded capacity three times in 2010 only to see growth stall. The next decade saw it utilise capacity only 35 to 45 percent. What this produced was a huge drag on profitability due to high fixed costs, and between 2013 and 2016, ACE reported a profit number in single digits.

The company used this time to fortify its product segments and ride out the down cycle. Already a leader in cranes, it expanded into construction equipment—backhoe loaders, rollers, forklifts for factories, and later into tractors and harvesters. A service network was strengthened and crane rentals were introduced.

As a result, when government capex picked up in 2016, ACE started seeing the first glimmers of change. In the year ended March 2017, ACE saw sales rise to ₹751 crore and profit to ₹14 crore. And in the year ended March 2018, sales were at ₹1,087 crore and profit at ₹54 crore. Clearly operating leverage was starting to kick in and the market started to notice.

Since then, sales are up a little under three times to ₹2,700 crore in the year ended December 2023, but profitability is up five times to ₹277 crore. In addition, the company is now using 85 percent of its expanded capacity with plans for one more round of expansion. Its order book stands at ₹6,000 crore.

The result of increased profitability is that ACE’s return on equity has moved to 29 percent. This makes the business hugely efficient and has resulted in the problem of what to do with the cash generated. There is capacity expansion that the company can spend on, there are acquisitions, which it is said to be exploring, and it could set up a finance company like other auto companies to finance the cranes it makes for customers, or it could return the cash to shareholders. This is a decision the Agarwals are still grappling with.

Over the last 12 months, ACE’s stock price has skyrocketed and with it, the family’s wealth. The stock is up by 269 percent in the last year, taking its market cap to ₹17,000 crore. It trades at a price-to-earnings multiple of 64. This has prompted the question as to whether it is pricing in too much of future growth. “I would disagree with this as the company still has several growth avenues it can tap into," says an analyst at a firm that has invested in ACE. He declined to be quoted citing company policy. Despite the increased valuation, his company is staying invested in ACE.

There is the export opportunity that brings in about 9 percent of revenue. That is ripe for growth. The company could use acquisitions to grow. It could also manufacture white label products for overseas clients. And an expansion in Ebitda margins is also on the cards as more operating leverage kicks in. Currently, margins are at 15.9 percent and Sorab sees scope for them to expand by 80 to 100 bps for every ₹500-600 crore of revenue. If revenues jump three to four times in the next five years, profitability should move up five times. That would bring valuations to a more manageable 16 to 18 times earnings.

Lastly, there is the risk of infrastructure spending slowing down once again as it did in the early part of the last decade. But having seen off that period, the Agarwals would be prepared to handle that. This time with plenty of cash on their books to ride out a downcycle.

First Published: Apr 25, 2024, 13:02

Subscribe Now