Fitness Chain Talwalkars' Competition is the Couch

When yours is the first name in Indian "gymming"

India is young, and it has gotten richer and fatter. This combination is swelling the revenues at the country’s largest listed gym operator—Talwalkars Better Value Fitness. The $28 million (revenue) Mumbai company makes its debut on the Best Under A Billion list this year. Revenues have more than tripled from 2008 and profits nearly quadrupled.

“Fitness has become a clinical necessity,” says Prashant Sudhakar Talwalkar, the 51-year-old chief executive officer and managing director, who spearheads gym expansions across the country. “Unhealthy lifestyles have given people a scare. Doctors are starting to prescribe exercise for everything from diabetes to high blood pressure.”

Talwalkars has expanded from 63 gyms in fiscal 2010 to 144 this year, and its membership has risen from 59,000 to over 1,33,000 for the same period. One “addicted” member is Chitra Narayanan, who hits the Talwalkars gym in the upscale Chennai neighbourhood of Alwarpet five times a week. Her sedentary job in IT ties her to the computer, so the 45-minute workout is important.

“There’s lots of positive energy when you walk into the gym,” says the 44-year-old mother of two. “It’s clean and nice.” She’s been “gymming” for six years and tried two other neighbourhood spots before settling on Talwalkars.

“They are very systematic,” she says. “They give you a card which tells you what you have to do each day. And there are floor trainers and physiotherapists who help you out.”

With a presence in 75 cities and 19 states, Talwalkars is pervasive enough to claim a national franchise, save for parts of eastern India. It owns 101 of the 144 branded sites. Even though the Indian economy is exhibiting signs of a slowdown, the company says it has not seen any significant impact on the business. In the current fiscal year it plans to add 20 to 30 fitness centres of different sorts.

Just in the past year it invested $15 million in capital expenditure, including opening new gyms, upgrading equipment and retrofitting existing fitness centres to accommodate Zumba (Latin dancing) and a new weight-loss programme, Reduce. These services are aimed at boosting net margins, which have already climbed from 12.6 percent in 2009 to 20 percent in fiscal 2013.

Much of the fitness industry has focussed elsewhere in Asia, but India’s demographics are enough to merit another look. Nearly 40 percent of India’s population will be in the 20-to-44 age group by the end of 2016, and many have increasing disposable income.

The fitness market is also nascent. Only 0.05 percent of urban Indians have a health club membership—compared with 3.11 percent in Asia-Pacific and 17.5 percent in the US.

The Talwalkars believe they have an edge in the business because of their long-standing presence in the Indian market. The legacy started with Vishnu Ramakrishna Talwalkar—Prashant’s paternal grandfather. Vishnu, who grew up in the village of Ashta in Maharashtra, got into wrestling because his village was near the stronghold of the erstwhile Maratha warriors.

He moved to Mumbai in the 1930s and started a training centre for wrestlers. In 1962, Prashant’s paternal uncle—Madhukar, who is now 79 years old and is chairman of the company—opened one of India’s first gyms, in Mumbai’s Bandra area.

Even though he completed a textile engineering degree from the prestigious VJTI and joined a mill as a spinning supervisor, Madhukar’s passions were bodybuilding and running gyms. So he veered from the cloth mill to the treadmill.

When Madhukar set up the first Talwalkars gym he was heartened by the demand. “People would travel 10 to 20 miles to come to the gym,” he says, and in the India of the 1960s that was really saying something.

But it was hard for the Talwalkars to meet the demand. “The initial growth was slow for the family business because financing was difficult,” says Prashant, who joined the business in 1982 after getting a degree in biology from the University of Mumbai.

The Talwalkars took the idea of a gym to everyone from celebrities to regular consumers who were interested in weight loss and fitness training. They built up their credibility because the family was personally involved in fitness. Madhukar, for instance, was the founder president of the Greater Bombay Body Builders Association. He still does weight training for one hour every day.

Prashant, for his part, grew up opposite a Talwalkars family gym. He started hanging out there when he was 7 or 8. He trained in judo when he was 15 and began bodybuilding in his early 20s. He still works out at least an hour daily. “I eat the same bread and butter that I sell,” says Prashant.

In 2003 Prashant joined hands with Madhukar and Girish, Madhukar’s son, to jump-start the expansion. They roped in three professionals to set up the company as it exists today. It listed on the stock exchange in 2010. (Prashant, Madhukar and Girish each own about 11 percent, and the non-family promoters each own about 7 percent.)

Talwalkars, which is perceived as a mid-tier brand, is now expanding at both ends of the spectrum. In smaller towns and cities it has started a no-frills, fully franchised chain called HiFi. At 2,500 to 2,800 square feet the HiFi gyms are half the size of regular fitness centres. Memberships cost 40 percent less than the full-service gyms.

Meanwhile, at the premium end, Talwalkars is rolling out a sports club. It raised $8 million (through a qualified institutional placement) in November and has tied up with David Lloyd Leisure, an upmarket health club operator in Europe.

But Prashant is the first to admit that it’s not easy to woo the masses. “I sell punishment—who likes to go out and exercise?” he asks. “My biggest competition is not the gym next door but the couch.”

Hence some of the special attractions. It has joined with Miami’s Zumba Fitness to offer Latin dancing—for $60 a month—both at its clubs and outside. The company has already trained more than 150 Zumba professionals and is looking to have 100 Zumba centres by the end of this fiscal year—up from the current 29.

It has also rolled out a weight-loss programme called Reduce, at $100 per month. This allows a person on a diet to eat regular meals in addition to special foods provided by the company.

“We have solutions for everyone,” says Prashant. “If you don’t like coming to the gym frequently we have something called NuForm, where you come only for 20 minutes once a week.”

He claims that NuForm studios help in weight loss through what he calls electro-muscle stimulation. At $600 to $700 per year, it’s targeted at the affluent consumer in tier-one cities.

As he broadens the offerings, Prashant’s focus is on retaining customers who walk in the door. In an industry where client churn is a rule of thumb, the company says it retains three out of four customers.

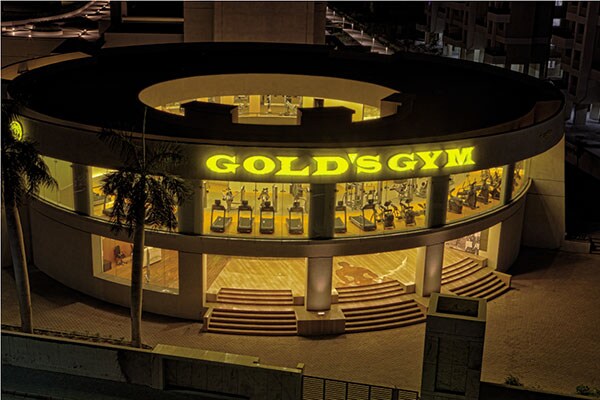

Although the market is highly fragmented and dominated by mom-and-pop players, Talwalkars faces its biggest competition from Gold’s Gym of the US. Through 10 years of franchising it has set up 92 gyms in India—its largest foreign presence. And it’s looking to grow to 150 by the end of 2014.

“India has lots of operational and infrastructural challenges,” says John Holsinger, Asia-Pacific director at the IHRSA trade group. “Gym operators have to deal with everything from the high cost of real estate to the availability of rentals in the right locations to getting the right qualified trainers. Sometimes it’s even difficult to get proper water facilities for the gym showers.”

Nonetheless, “we’ve seen explosive development in India over the past decade,” says Tim Hicks, director of franchising at Gold’s. “We have become the preferred gym of many Bollywood celebrities. We are very bullish on growth in India because of the low gym penetration.”

Gold’s Gym has visiting doctors who provide consultation to members on diabetes, cholesterol and hypertension. Trainers customise the workout programmes for these clients.

Meanwhile, Portugal’s Vivafit, signing on three franchisees to cover the southern, northern and eastern parts of India, has carved out a niche by catering only to women.

First Published: Sep 02, 2013, 06:30

Subscribe Now