America's War Over Uranium Fracking

Deep in the heart of the Texas oil and gas boom, a tiny Canadian company has found a novel way to dredge up fuel for nuclear reactors. And it's prompted the most unusual battle in America's war over f

No tour of Uranium Energy Corp’s processing plant in Hobson, Texas, is complete until CEO Amir Adnani pries the top off a big black steel drum and invites you to peer inside. There, ï¬lled nearly to the brim, is an orange-yellow powder that UEC mined out of the South Texas countryside.

It’s uranium oxide, U3O8, otherwise known as yellowcake. This is the stuff that atomic bombs and nuclear reactor fuel are made from. The 55-gallon drum weighs about 1,000 pounds and fetches about $50,000 at market. But when Adnani looks in, he says, he sees more than just money. He sees America’s future.

“The US is more reliant upon foreign sources of uranium than on foreign sources of oil,” says Adnani, who himself was born in Iran and looks out of place in South Texas with his sneakers and Prada vest.

America’s 104 nuclear power plants generate a vital 20 percent of the nation’s electricity. Back in the early 1980s, the US was the biggest uranium miner in the world, producing 43 million pounds a year—enough for nuclear utilities to source all the fuel they needed domestically. But today, domestic production is down to 4 million pounds per year.

Perhaps worrisome, the country’s biggest supplier is cutting it off. For the past 20 years, America bought 20 million pounds a year from Russia, courtesy of dismantled nuclear weapons. But in 2013, the $8 billion Megatons to Megawatts Program comes to an end. Growing production from Kazakhstan (39 million pounds per year), Canada (18 million) and Australia (12 million) will ï¬ll the gap. But China, with 15 nuclear reactors, 26 in the works and 100 more planned, will increasingly compete for these ï¬nite supplies.

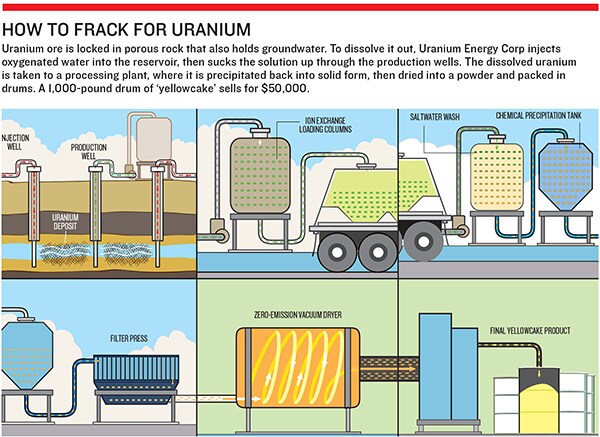

Adnani insists that he can close the yellowcake gap through a technology that is similar to the hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, that has created the South Texas energy boom. Fracking for uranium isn’t vastly different from fracking for natural gas. UEC bores under ranchland into layers of highly porous rock that not only contain uranium ore but also hold precious groundwater. Then it injects oxygenated water down into the sand to dissolve out the uranium. The resulting solution is slurped out with pumps, then processed and dried at the company’s Hobson plant.

Standing next to a half-dozen full drums of UEC’s yellowcake, we’re not wearing any protective gear, save a hard hat. We don’t need to. The uranium emits primarily alpha radiation, easily stopped by our skin. That doesn’t mean yellowcake is safe. Inhaling or swallowing it—in drinking water, for instance—can cause kidney and liver damage or cancer.

That’s why Adnani’s plan has prompted concern in a region other- wise nonchalant about environmental impacts on health and comfortable with the risk-reward ratio that comes with fracking. This part of Texas is in the core of the Eagle Ford shale, currently the most proï¬table oil and gas ï¬eld in the US. The people around here understand that the fracking of this shale, the injection of billions of gallons of sand-and-chemical-laden water, takes place 2 miles beneath the ground. They know that steel pipe cased in concrete, when engineered correctly, is not going to leak chemicals into their water.

UEC’s process doesn’t take place 2 miles down. Rather, it’s dissolving uranium from just 400 feet to 800 feet down—not only from the same depths as groundwater but from the very same layers of porous rock that hold it. “By design it’s much worse than fracking,” says Houston attorney Jim Blackburn, who is suing UEC on behalf of residents near the company’s new project in Goliad, Texas. “This is intentional contamination of a water aquifer liberating not only uranium but other elements that were bound up with the sand. We know this process will contaminate groundwater that’s the whole point of it.”

UEC argues that it is doing the environment a favour. “We’re taking out a radioactive source from the aquifer that won’t be there for future generations,” says Harry Anthony, UEC’s chief operating officer. Adnani adds: “The water is already polluted. Uranium is so close to the water table such that by-products like radium and radon are already in the water. We’re pumping water out of the polluted aquifers and reinjecting less radioactive water.”

Such analyses haven’t molliï¬ed critics. But they’ve proven enough for this unknown company to move full steam ahead. “The Eagle Ford,” smiles Adnani, “will be the site of a uranium boom.”

Adnani’s putative uranium boom is 45 million years in the making. Back then, volcanoes dotted West Texas and New Mexico, blanketing the countryside in a thick layer of ash that contained uranium and other elements. As uranium is easily dissolved by water, most of it washed out into the Gulf of Mexico over the millennia. But enough got stuck along the way—converted into solid ore when it came in contact with natural gas bubbling up from below—to produce one of the largest uranium deposits in the US.

Enter UEC, which already has one mine in operation, a second under construction and a handful more in the works, making it the most notable uranium producer in South Texas. As companies go, it’s still a pip-squeak. Founded in 2005 in Vancouver, its roots are more in marketing than mining. Before UEC, Adnani, just 34, was founder of Blender Media, an investor relations ï¬rm catering to speculative Vancouver mining companies.

Adnani’s co-founder was his father-in-law, Alan Lindsay, 61, who, in the words of Citron Research analyst Andrew Left, “has left behind nothing but companies that have promised high hopes and left investors with empty pockets”. That would include defunct or bulletin-board ï¬rms like Strategic American Oil, Phyto-medical, TapImmune and MIV Therapeutics. Adnani says that as non-executive chairman of UEC, Lindsay has no day-to-day role with the company. And besides, he says, when Left critiqued UEC a couple of years ago, “we hadn’t produced a pound of uranium. Since then we have executed on everything that Citron said we wouldn’t be able to do”.

UEC is listed on the American Stock Exchange and the Frankfurt Stock Exchange. BlackRock, Oppen- heimer Funds and the closed-end Geiger Fund all hold large chunks, and the company boasts a market capital- isation of $250 million, despite a net loss of $25 million in the past year on yellowcake sales of $13.7 million. Over ï¬ve years, it’s run through more than $100 million, though money from follow-on stock offerings have kept it debt free, with $17 million in reserve. Shares peaked at $6.70 in the months before Fukushima. They’re down to $2.45 now.

UEC inherits a chequered legacy. From the 1950s through the early 1980s, big oil and chemical companies like Union Carbide, Exxon, Chevron, Conoco and even US Steel mined uranium in South Texas. Not only did they ï¬nd a lot of the stuff while hunting for oil and gas, but the federal government, amid the Cold War, even required that they also run tests in every oil and gas well to check for the presence of uranium. The oil companies sold their yellowcake to the government for the production of nuclear weapons and reactor fuel. “Back then, every company was down here,” recalls Anthony, who was a young engineer for Union Carbide. “This was the stomping ground.”

But in the process, they made a mess, gouging out muddy pit mines and building tailings ponds to hold toxic sludge left over from processing ore with acid. A uranium mine in Karnes County was designated a Superfund site it remains polluted, as does the nearby Falls City uranium mill site, where, the Department of Energy says, “contaminants of potential concern are cadmium, cobalt, fluoride, iron, nickel, sulphate and uranium”.

In 1987, dozens of local ranchers began raising questions about the Panna Maria uranium processing mill and dumping grounds that Chevron operated near UEC’s plant in Hobson. Chevron later sold its uranium operations to defence contractor General Atomics, which cleaned up the site. Even so, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission reports that groundwater “remains an outstanding issue”.

UEC’s flagship site, Palangana, has had its share of trouble. Palangana’s uranium hoard was discovered in the 1950s. In 1958, Union Carbide took the ï¬rst whack at developing an underground mine there but abandoned efforts because of high levels of hydrogen sulphide gas. Union Carbide tried again in 1967, using what were brand new in situ recovery techniques and drilling thousands of holes. But instead of using oxygenated water to dissolve the uranium, the company injected ammonia, which reacted poorly to clay in the earth. Recovery rates were disappointing in 1980, Union Carbide sold Palangana to Chevron.

Chevron ï¬gured there was enough uranium left at Palangana to justify an open pit mine, but when uranium prices fell in the 1980s, it shelved the idea and in 1991 sold Palangana to General Atomics, which spent years trying to clean up groundwater before ï¬nally getting the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to allow it to leave slightly higher levels of pollutants than were there before mining. In 2009, UEC acquired Palangana and the Hobson plant from Everest Exploration and its partner, Uranium One, for $1 million and 2.7 million shares of stock, then worth $10 million. It has since invested more than $10 million to clean up another nearby Everest site and to build out Palangana for a new generation of uranium fracking.

So, after a history of mining messes can Texas ranchers now trust UEC in its Goliad project? UEC’s Anthony says there’s nothing to worry about. “I live a mile away from two uranium mines, and I drink the water out of those aquifers,” he says.

But Goliad sceptics have been ï¬ghting UEC’s plans for ï¬ve years. At Goliad, the uranium ore is located just 400 feet deep within the same rock as a groundwater reservoir that ranchers tap for drinking water, both for themselves and their livestock. Water, not oil, is the region’s long-term liquid gold. “We are running out of water I don’t want mine ruined,” said one rancher who asked not to be named. “When you’re out of water, you’re out of everything.”

She has reason to be skittish. A 2009 study of Texas in situ mines by the US Geological Survey determined that the groundwater around uranium deposits is naturally high in junk like arsenic, cadmium, lead, selenium, radium and, of course, uranium. Though levels of some pollutants ended up lower after mining and remediation eforts, the USGS found no instance in which there wasn’t more selenium and uranium in the water than before mining.

An investigation of 76 in situ mining sites by geoscientist Bruce Darling done on behalf of locals in Goliad County concluded that producers’ inability to sufficiently reduce concentrations of uranium (and other pollutants) “calls into question the operators’ understanding of the geochemistry of the hydro-geologic systems that they are exploiting”. A study of in situ leaching for the Natural Resources Defense Council by University of Colorado hydrogeologist Roseanna Neupauer found that “contaminants will remain in the aquifer after all efforts at restoration and will migrate through the aquifer into the future”.

The Texas Railroad Commission, which regulates mining in the state, gave UEC the permit to do exploratory drilling at Goliad. Then in 2007, UEC was investigated and sued for failing to properly plug exploration wells, allegedly leading to groundwater pollution. A federal judge found reason to believe UEC had acted improperly, but he had no choice but to dismiss Goliad County’s suit to block further drilling because his court lacked jurisdiction. In 2008, Goliad County urged the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, another regulatory agency, to turn down UEC’s production drilling permits. That request was denied.

Harry Anthony insists that technology breakthroughs make older failures largely irrelevant. He adds that the sections of the aquifers UEC will be mining contain only non-potable water to begin with and that the ring of monitor wells it will install around the site will detect any movement of dissolved uranium beyond the production wells. Because the vacuum pressure of UEC’s pumps suck solution up the production wells, “the groundwater flows towards our wells. So it sweeps up anything that shouldn’t be allowed to get away. It’s a simple process, just tedious to do it right.”In December, to help placate any sceptics, Adnani signed up Spencer Abraham, former Secretary of Energy in the George W Bush administration to head UEC’s advisory board. Natu- rally, Abraham is not worried. “The United States has the world’s most stringent mining regulatory standards ï¬rmly in place,” says Abraham in an email exchange. “Uranium mining activities, including those undertaken by Uranium Energy Corp, are being performed in line with the highest recognised safety standards.”

And to put a bit of money where its mouth is, UEC has posted $5 million in surety bonds that will go towards eventual reclamation efforts. Says Anthony: “There will be no degradation to the water of the state of Texas.”

The stakes are sizeable. The Hobson plant has the capacity for one million pounds of ore a year, ï¬ve times as much as it does now. With the Goliad project and a handful of other prospects, UEC aims to get to 3 million pounds a year before the end of the decade.

That kind of output dovetails with Adnani’s nuclear rhetoric. “Even after Fukushima, there is a nuclear building boom worldwide,” says Adnani. “And even without new reactors coming online, demand will outstrip supply.” That’s especially true in the US, which, despite the stain caused by Fukushima, is slowly inching toward a nuclear renaissance. The Tennessee Valley Authority is building a new reactor at its Watts Bar site. Scana is building two in South Carolina, while Georgia Power, a division of Southern Co, is also building two at its Vogtle power station. These will be completed around 2016 at a cost of some $30 billion.

Where Adnani’s rhetoric falls short is the need for domestic uranium. America’s nuclear utilities aren’t worried about being able to source it, says Jonathan Hinze, analyst with Ux Consultants, which studies market trends for miners, power utilities and institutional investors. Reactors get refuelled only once a year, so supplies don’t need to come from nearby. Besides, Hinze says, uranium buyers and sellers have planned for the end of the Megatons to Megawatts Program for a long time. “Even if prices tripled from where they are today it would not impact the bottom line for utilities because fuel is just a small part of their operating cost,” says Hinze. And at higher prices, Canada, Kazakhstan and Australia have a lot more uranium to go after. “The US is not blessed with the same resources.”

That’s why for Blackburn, and the people he represents, the idea of a tiny company gambling a region’s groundwater on a market that may never appear seems nothing short of insane. “There’s no source of water here other than groundwater,” says Blackburn. “How can you mine inside a drinking water aquifer?”

And yet it is happening. Last month, UEC received the last permit it needed: An aquifer exemption from the Environmental Protection Agency. Construction and drilling at Goliad has begun—and UEC has leased more than 20,000 acres in the area. The company plans to be producing uranium there by the end of this year.

First Published: Mar 05, 2013, 06:49

Subscribe Now