Billionaire Investor Carl Icahn's Tale of Aggression

Freed from investors and flush with cash, Carl Icahn is targeting companies by the dozen. The bigger, the better (just ask Michael Dell)

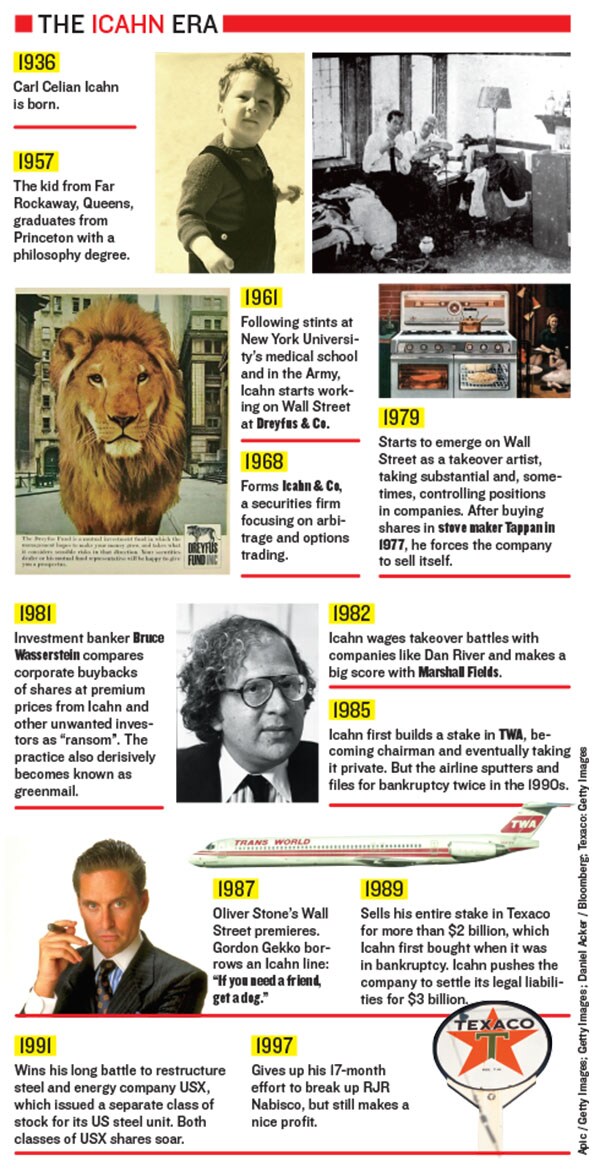

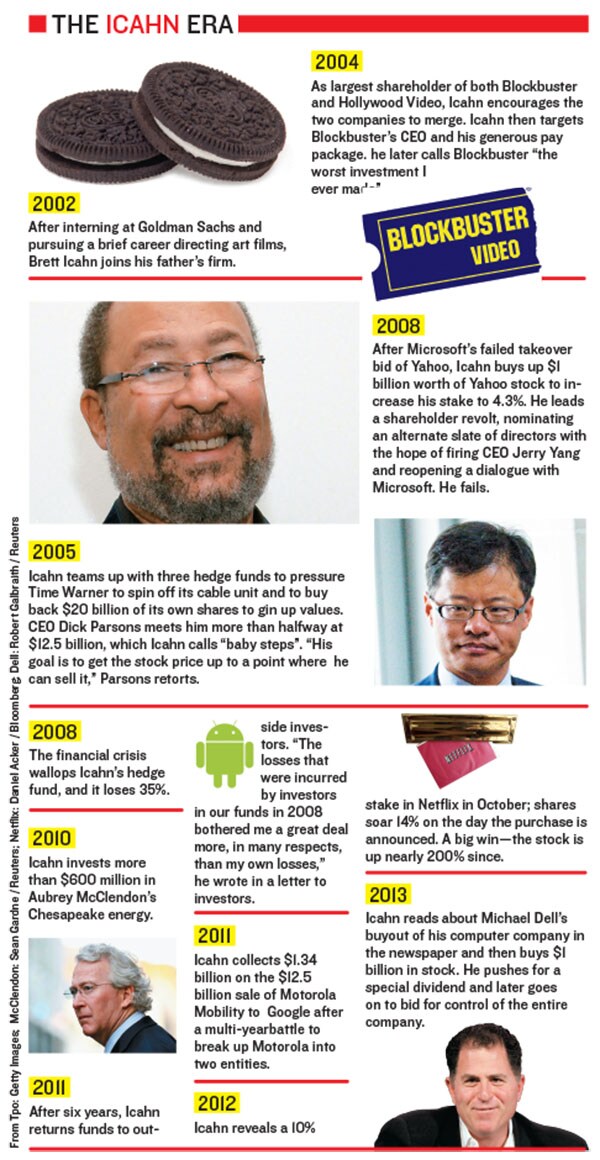

Carl Icahn’s offices carry a distinct museum quality. Three decades of scalps, resulting from some of the most famous hostile takeovers, proxy fights and board assaults in American financial history, cover every cranny of his wood-lined corridors. There are model airplanes from TWA—the takeover that cemented his name among major league dealmakers—and toy trains from ACF Industries, which has served as his cash machine for decades. Lucite tombstones recount conquests involving many of the great companies of the 20th century, from MGM to Motorola, Texaco to Nabisco.

Yet Icahn’s backward-looking perch, near the top of Manhattan’s old-school GM Building, has never been more relevant, as forty something billionaires like Michael Dell and Bill Ackman are learning to their chagrin. In the last 15 months, the 77-year-old has taken positions in and then launched campaigns against 14 companies, a burst that has made him, at an age when he would have long been expected to fade away, the most disruptive individual in business, with a hand in almost every major corporate story in America.

One moment he’s launching a full-blown bid to snatch Dell from its eponymous founder. The next, he’s needling deepwater driller Transocean to pay out a gusher of a dividend. When there’s good news at Netflix, money managers shake their heads at Icahn’s timely investment. And if you stand in his way? His fingerprints were all over the resignation of Chesapeake Energy’s notorious Aubrey McClendon. Meanwhile, his live CNBC brawl with Ackman, who’s on the other side of his position in controversial vitamin company Herbalife, lit up trading floors around the world.

All of which leaves Icahn decidedly … relaxed. His face gives it away: He now sports a scholarly white beard, a byproduct of a recent jaunt to Miami. And his demeanour backs it up: Icahn sold his 177-foot yacht because he got bored spending time on it the investor has discovered that, for him, happiness means pursuing his activism actively.

“What else am I going to do?” Icahn asks rhetorically. “Sit at boring dinner parties?” He says this with a wave of the hand, leaning back in his chair. He’s a few days away from making an unsolicited bid for Dell, recently valued at $25 billion, offering to put up a $5 billion equity commitment funded almost completely out of his own pocket. Yet he’s as nonchalant as if he were mulling whether to help a buddy open a Dairy Queen franchise. Clad in a blue blazer with gold buttons, he calmly sips on a straw that delivers Coke from a crystal cup. “We’re at the top our game,” he says. “There’s never been a better time to do what we do.”

To be frank, though, what he does has changed. He used to make runs at companies via junk bonds and other tools of leverage. Then he figured out how to use other people’s money via a hedge fund structure. Now, though, it’s all Carl—with a net worth that Forbes estimates at $20 billion (which makes him the richest Wall Streeter, edging out George Soros). He doesn’t need anyone’s help or approval anymore. And that now makes him very, very dangerous.

“He loves winning, and he loves money—but it’s just a scorecard to show he’s recognised value and won,” says finance billionaire Leon Black, Icahn’s investment banker at Drexel Burnham Lambert in the 1980s before co-founding private equity giant Apollo Global Management. “He is smart and unrelenting, he doesn’t care what other people think and even though he is not always right, I would never bet against him.”

While Icahn’s re-emergence has taken Wall Street by surprise, it’s actually the result of five years of careful planning. Icahn had spent the 2000s making hundreds of millions of dollars the new-fashioned way: Creating a hedge fund structure, so that he could invest his own money alongside people willing to give him 2.5% of their investment, plus 25% of their profits, for the privilege. By 2007, he was managing as much as $5 billion in outside capital from endowments, pension funds and even a Middle Eastern country. It worked wonderfully until his funds lost more than 35% of their value during the economic meltdown. Suddenly, like most fund managers, he faced disappointed investors and let cash-strapped partners redeem their funds.

Instead of scratching back his assets under management, Icahn cut himself loose from the burden of limited partners entirely. He returned the remaining $1.76 billion of outside capital in his hedge fund in 2011. “I never had a problem with my investors,” says Icahn. “But in the end, there were too many conflicts when you wanted to buy a hundred percent of a company.” Rather than be a fee-earning fund manager, he would reboot as a lone wolf, armed with a jumble of personal investment pools commingled with the funds of his publicly traded vehicle, Icahn Enterprises LP. (The public company, of which he owns over 90%, holds $24 billion in assets, including majority stakes in eight companies, such as auto parts maker Federal-Mogul.)

Over the past four years, Icahn’s investment funds have outperformed the S&P 500 Index, averaging returns of more than 25% a year, a feat few hedge fund managers can claim. He’s off to another good start this year—with his investment funds up 12% through March 13. More impressive, Icahn claims his portfolio has largely been hedged in the last few years—his stock holdings offset by large short positions of the S&P 500 Index. At the same time, Icahn Enterprises has outperformed the US stock market over the same period. As a result, Icahn, who was worth perhaps $9 billion at the bottom of the market, has quickly doubled up.

That brings us to today. With no one to answer to except himself, Icahn is unleashed. He has never had so much cash. Nor have the balance sheets of corporate America. This confluence translates into Icahn’s recent fox-in-the-henhouse antics, as he’s now perfectly positioned to wield his fear-inducing brand of activist investing—shaking up companies by snatching up their publicly traded stock, grabbing board seats and demanding they do something with their cash.

“He has the guts to do things in size and make big bets, and, frankly, he has more money now than ever,” says Keith Meister, a former Icahn lieutenant who now runs his own $2 billion-plus hedge fund. “Activists have become cults of personality, and there is no one bigger and better than Carl in that world.”

Icahn says he respects the new breed of activist investors like Meister, Daniel Loeb and Barry Rosenstein. (“Good guys,” he calls them.) But what separates him is that they run money that can be recalled by their investors. Icahn, by virtue of his post-meltdown revamp, wages proxy battles and issues tender offers with so-called permanent capital—money under his complete control. And given how large that permanent war chest is, he can target companies previously thought unassailable. “Right now,” says Icahn, waving around an aluminum ruler like a cavalry saber, “without selling anything, we can write a cheque for about $10 billion.” With that kind of ammo, Icahn can take on a cash-rich company with a market cap of as much as $50 billion.

That puts Dell, the world’s third-largest personal-computer maker, in his sweet spot. In February, Michael Dell seemed to have an unimpeded way to regain control of the company he had founded in his college dorm room, working with private equity firm Silver Lake on a $24.4 billion deal to take Dell private for $13.65 per share, a 25% premium over its recent trading price.

Icahn read about it in the newspaper, and he swiftly took a $1 billion position in the stock, figuring that if Dell was putting so much money in, it must be really cheap.

By early March, Icahn had concluded that Michael Dell’s bid did not reflect the company’s stated 15% internal rate of return on its $13.7 billion of infrastructure technology acquisitions. So he implored shareholders to force the company to scrap the deal and instead pay $9 per share in dividends using its own cash and new debt.

By the middle of the month, Icahn was pondering a more forceful tactic, mindful of the fact that the company’s founder had already established a floor. And towards the end of the month, he notified the special committee of Dell’s board of directors that he was interested in buying control of the company. A bidding war between him, Michael Dell and the Blackstone Group private equity firm is expected to play out over the next weeks. Given Icahn’s big bet, he almost certainly wins even if he loses.

This is a game Icahn has mastered—and loves. Forbes interviewed Icahn approximately a dozen times for this story as the Dell saga unfolded. At first, he was coy about his plans for Dell. As the month rolled on, the lecturer emerged: “Michael may have messed himself up,” says Icahn. “He put himself in a position where he may lose his company, since normally it would have been very hard to take his company away, because he owns 15%.” And in the days leading up to his formal buyout offer, you could feel Icahn brimming, already developing plans for the possibility of a Dell without Michael Dell.

Although it seems like he’s everywhere, Icahn rarely leaves his billionaire bunker in the GM Building to do business. There are few plane rides to shareholder meetings or lawyers’ offices. He can make the big changes to companies from Manhattan and insists he doesn’t need to micromanage. “That’s like watching a doctor operate and telling him he’s doing it wrong,” says Icahn. His ideas often come from what he observes in broad daylight, and if he’s interested in something, the world comes to him—or else he just picks up the phone. As we learned in Charlie’s Angels, the man who’s just a voice at the end of a line can nonetheless wield great power.

Even when he appears on television, such as for the Ackman battle royale, Icahn phones in, and the network flashes a years-old stock photo as he speaks. The Forbes cover shoot marks the first time in some six years that Icahn has sat for a portrait, and it’s the first time the public has seen his new hirsute look.

It took a half-century for the pendulum to swing fully in this direction. For the first part of his career, Icahn was the one traveling for meetings. The only child of a synagogue cantor and his teacher wife, Icahn worked his way from the rough neighbourhood of Far Rockaway, Queens, to Princeton (“I think they wanted to do an experiment,” he says) and then, after dropping out of med school, jumped from the Army to Wall Street, where his uncle got him a job in the early 1960s as an options broker. That led to risk arbitrage and some small-time buyouts. He was perfectly positioned by the 1980s to make serious money and headlines as a junk-bond-fuelled hostile takeover artist.

Today, Carl Icahn’s visceral response to the word “raider” is almost comical. He has fully absorbed the semantics surrounding the concept of an “activist”, leading the abused shareholders against lazy or corpulent management, in the manner of Les Miserables. In March, legendary securities lawyer Marty Lipton, 81, inventor of the poison pill defence tactic, fired off a memo about activist investors like Icahn, questioning if they are responsible for significant parts of America’s unemployment and meagre GDP growth. “In what can only be considered a form of extortion,” Lipton wrote, “activist hedge funds are preying on American corporations.” Icahn’s retort: “I respect Marty, but he’s dead wrong.”

The activist roots certainly lie in the raider days. There’s no getting around the groundbreaking, and head-breaking, TWA takeover, and his prominent role at Michael Milken’s annual Predator’s Ball.

But whereas Milken and Ivan Boesky did jail time, and as Victor Posner and Saul Steinberg passed on and the likes of Meshulam Riklis and Samuel Belzberg faded away, Icahn was able to adapt, even after various governments and regulators cracked down on the junk bond era’s most successful tactic, greenmail (when companies bought back shares at a premium to halt a takeover).

Icahn now describes his business philosophy as Graham & Dodd investing with a kick and is prone to compare himself with the greatest Graham & Dodd practitioner ever, Warren Buffett. Since 2000, Icahn Enterprises has had a total return of 840%. Berkshire Hathaway? 250%. Yet the markets value Buffett’s involvement at a premium, while you can buy Icahn enterprises at a discount to net asset value. That’s because, despite Icahn’s comparison, there’s little in common between the two, other than a desire to shake up the world at an age when most of their peers stay sharp with crossword puzzles. Buffett looks for market inefficiencies involving great companies, which he buys with an intended holding period of “forever”. Icahn will occasionally hold on to companies, but his time horizon is far more erratic. His deal prism runs through the chip on his shoulder and his thirst for the kill, two traits that hold whether you’re a raider or an activist.

For instance, Icahn does not even need to be prompted about Ackman. “Ackman would not have lasted long on the streets of Far Rockaway,” Icahn volunteers. “One thing that makes Bill Ackman the opposite of me is that to be a true winner you have to learn to win gracefully. Ackman will never be able to do this.”

Ackman’s big transgression is a measly $9 million that the 46-year-old hedge fund manager won from Icahn during a seven-year legal battle over something called Hallwood Realty. “I’m a big boy I’ve been up against the best of them, and sometimes they win and I congratulate them and I’m still friends with them,” says Icahn. “But this guy goes and gets articles written about how he beat Carl Icahn, and in an extremely nasty way.”

And so Icahn has spent a lot of this year repaying the nasty. The CNBC slugfest, where Icahn called Ackman a “crybaby in the schoolyard” and a “sanctimonious” liar, was simply a public spanking. The private pain started in December, when Ackman began promoting his $1 billion short position in Herbalife—and driving down the vitamin maker’s stock price.

Icahn gobbled up the cheaper shares to the tune of a $600 million position. That pushed the stock up, squeezing Ackman. He put representatives on the company’s board. And while Icahn says he’s in the stock to make money, he also concedes that torturing Ackman makes the play more enjoyable. (Ackman declined to be interviewed for this article.) “He is stuck in that short—20 million shares short won’t be easy to cover,” says Icahn. When you have no one to answer to, vendetta as investment strategy is as legitimate as anything.

Icahn’s noisy battles get the headlines, but he has quietly become perhaps the biggest beneficiary of America’s hydraulic fracturing revolution, which has unlocked huge oil and gas reserves.

For decades, Icahn has owned a massive fleet of oil-carrying railcars that, if lined up, he claims, you could walk on from Manhattan to Ohio without ever touching the ground. He also owns two railcar producers, ACF Industries and the Nasdaq-listed American Railcar Industries. Demand and lease prices for these cars have surged as the Midwest fracking boom has yielded an ocean of oil. Shares of ARII have jumped 75% since last March as producers scramble for tank cars to ship fuel across America.

Railcars have been shipping cash flow to Icahn’s exploits for years. He bought ACF in 1984 for $469 million and immediately sold off three divisions for $360 million and fired most of the 180 people employed in its New York headquarters (he says neither he nor hired consultants could figure out what they were doing). He would later use ACF money to arrange financing for many of his takeover attempts, including his $4.2 billion tender for 45% of Phillips Petroleum, when he faced off against T Boone Pickens.

But his newfound oil riches can be traced to CVR Energy, arguably the best deal Icahn has ever made. He first took a position in the oil refining company in January 2012, and by the summer he owned 82% of its shares and had replaced its board. Icahn has made $2 billion as its stock doubled with more and more oil flowing to its refineries. Part of this was luck: He failed to sell the company just as the stock began to take off. But part was unmistakably Icahn: He pushed CVR management to IPO some refining assets into a master limited partnership, betting correctly that it would be attractive for yield-starved investors—shares are up 35% since.

Then there is natural gas giant Chesapeake Energy, perhaps the most visible fracking beneficiary. While building Chesapeake, McClendon ran a secretive commodities hedge fund on the side, used minority stakes he took in Chesapeake’s wells as collateral for loans and made madcap corporate investments that added to a massive debt load. Forbes called him “America’s Most Reckless Billionaire” on its cover. Yet nothing, it seemed, could dislodge McClendon from his spot atop Chesapeake—until Icahn came along.

Icahn first invested in Chesapeake in 2010 and demanded that the company unload assets to reduce debt. McClendon complied, selling a couple of fields for some $6 billion and causing the stock to spike. But when Icahn looked McClendon in the eye and asked to put a representative on Chesapeake’s board, he refused. “We said to ourselves, the selling is over, he is never going to sell again,” says Icahn. And so Icahn did, instead: “We sold everything and made $500 million.”

Icahn rebuilt a position in the stock a year later. Swarmed by allegations of insider dealings and in need of support, McClendon this time welcomed one of Icahn’s chief lieutenants, Vincent Intrieri, on the board. By this January, McClendon had announced his retirement, citing “philosophical differences that exist between the board and me”. The stock has since risen. McClendon declined to comment, and Icahn will only say that “I respect what Aubrey has done, but he is not a cost-cutting kind of guy”. This time around, Forbes estimates, Icahn has made another quarter-billion dollars on Chesapeake.

If many ageing executives retire to spend quality time with their families, the Icahns are doing the opposite. With dad not slowing down, the kids are working at the firm and spending more time with him. Son Brett, 33, has been with Icahn for 11 years and now scouts deals for Pop as co-manager of the Sargon portfolio (he and another rising star working for Icahn, David Schechter, brought forward the Netflix investment). Daughter Michelle, 30, worked as a schoolteacher and will start at the firm soon.

They join a nonbureaucratic shop of 20 investment professionals and lawyers. There are no stuffy investment committee meetings. Instead, there are late nights with Icahn building convictions by drilling down on two or three core issues, and lots of phone calls. Icahn starts dialling the moment he wakes up, often delaying his trip to the office until midmorning. “You have to be transparent and accessible those are two very important things with Carl,” says Greg Brown, chief of Motorola Solutions, who got calls from Icahn waking him up in China, even interrupting his attempt to get away for his wedding anniversary, in the years Icahn was invested in his company. “And performance: If you aren’t moving the needle, you are in trouble.”

Reed Hastings, the CEO of Netflix, is learning to accept Icahn since he took a 10% stake in the company last fall. Icahn’s purchase prompted the company to adopt a so-called poison pill to prevent Icahn from buying more shares. “It’s like a chess opening. He does that move, and we do the pill,” says Hastings. “I was worried about him when we didn’t know him, but I now must say that I enjoy his company.” Responds Icahn: “We like Reed Hastings. I told him when a guy makes me 800 million bucks, I don’t punch him in the mouth.”

Nonetheless, an entire industry of bankers and lawyers, “mercenaries like Goldman Sachs”, as Icahn puts it, has sprung up to protect CEOs and corporate boards from Icahn’s stinging jabs. Given the balance sheets out there, they’re going to be busy. “All this cash is dammed up at these companies,” says Icahn. “We are the catalyst to enable them to do something with it.”

Rest assured, Icahn will be taking notes about who’s helping him break the dams and who isn’t. Netflix chief Hastings earned a reprieve after he turned around company results and the stock shot up. By contrast, when he took control of CVR Energy in May 2012, Icahn’s team noticed that Goldman had racked up an $18.5 million fee trying to fend them off. They instructed the company not to pay it. Such are the consequences when you’re on the wrong side of a guy mad enough to fight on principle—and rich enough to win.

ENTREPRENEURS CLINIC

ENTREPRENEURS CLINIC

Last year, Brett Icahn, 33, was handed up to $3 billion to invest for Icahn Capital. But he’s had to prove himself in the 11 years he has worked for his dad. (Daughter Michelle will join this spring.) What’s the best way to bring your kids into your business? Carl Icahn off ers his advice:

START EARLY. Over the years, Brett and I would take long walks every weekend. He was very responsive, always interested. He has a real good mind—and he learned by osmosis. Brett saw me working all the time. Some of my cynicism about the business and Wall Street—he inherited that. He’d listen and learn a lot he has a good talent for it. He took courses in accounting so he’d understand balance sheets. People in the offi ce taught him a lot, too. We’d look at diferent stuff and dig into it. He picked it up very well. He’s not one of those spoilt rich kids.

TREAT THEM LIKE NORMAL EMPLOYEES. This isn’t nepotism. You say, “Hey, look, you’re working here like everybody else: You start at the bottom and you get no perks and you have to understand that.” You’ve got to be almost tougher with them than anybody else. You don’t want others to think he’s got an advantage. Brett was always sensitive to that. Sometimes I only had the top two guys in the fi rm at a meeting, and I’d say, “Hey, Brett, come in here, you might learn something.” And he’d say, “Look dad, unless you bring in the other three guys I work with, I shouldn’t go in.”

TEST THEIR METTLE. When Brett and his partner, David Schechter, started the Sargon portfolio, they said, “Give us $300 million,” and I said, okay, I had the right to veto anything they did. They gave up their salaries to take a small percentage of the profi ts. There was a hurdle rate. This way it was their baby. The choices they made were a little bit diff erent from what I would’ve done—they were more in growth areas, in technology—but they did great with it, basically doubling the money. And in the new $3 billion investment portfolio, they’re up $720 million since they started last August.

First Published: Apr 17, 2013, 06:35

Subscribe Now