The Success Story of Shriram Transport Finance

R Thyagarajan's Shriram Transport Finance has kept investors and shareholders happy, several times over. He spells out the small secrets of his huge success

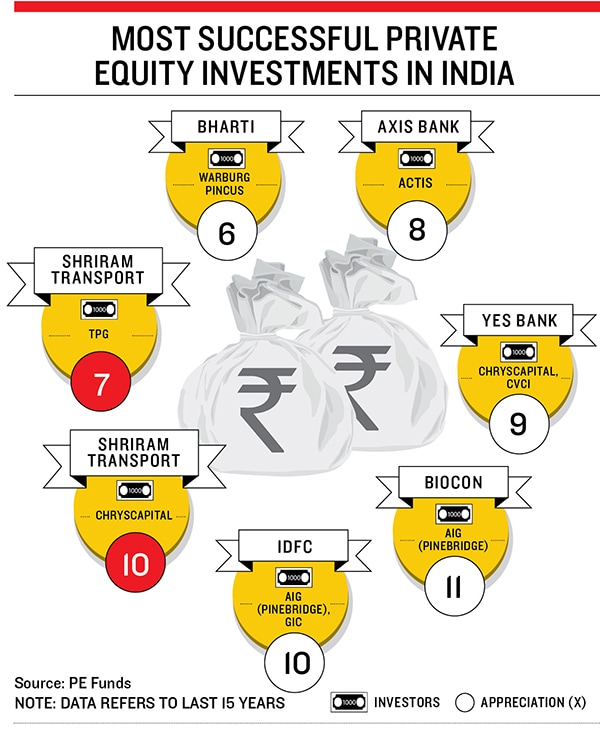

Entrepreneurs create wealth, for themselves and for those who invest money or sweat in their labours. The man who has been held up as icon for wealth creation in liberalised India is Sunil Mittal: Bharti became a world-class organisation in just about 15 years, and the firm that invested in it, Warburg Pincus, made close to six times the invested amount and a profit of almost $1 billion.

Though no other company has delivered such a large amount of profits, there are at least five other companies that have delivered huge returns for investors (see graphic). However, there is one firm that is special even within this small club: Shriram Transport Finance has delivered large returns for not one but multiple investors ChrysCapital made 10 times its investment a few years ago, and TPG made seven times its investment a few weeks ago when it sold its stake in the company.

Consider this: Over the past decade, Shriram Transport’s share price has gone up a mind-boggling 70 times, while Bharti Airtel’s has gone up about 25 times. Sure, the two businesses are very different. But if Bharti’s is tricky with regulatory risks, Shriram’s—which started off with financing the small truck owner—is no less treacherous.

Ashish Dhawan, earlier with ChrysCapital and now with Central Square Foundation, believes the secret behind Shriram’s success is the formidable R Thyagarajan. He built the company through internal accruals and debt over 20 years before accepting any private equity. By then, his processes were rock-solid.

Dhawan points to two key things Thyagarajan did to make this risky business work: “Shriram’s field officers know their customers and their needs really well. Thyagarajan also put in a system where the person who acquired a customer was the one who also collected the money from him.”

These are important things, but even more crucial is Thyagarajan’s approach to business itself, which is a mix of the earth and the pragmatic. This is what the 70-year-old had to say about his approach. Not having a cellphone is a beginning.

No cellphone

A doctor needs a cellphone because his patients may need urgent attention. There are professions in which a customer benefits if he can reach you urgently. I am not in that sort of a business. I am of no use to anyone in an emergency. I also don’t like to carry anything too heavy on me. Before I get down to work, I take off my watch. I don’t carry a purse, just some 10-rupee notes or 50-rupee notes.

Trust people

I cannot distrust people. I don’t start with suspicions. This goes for private equity investors or partners. In 1990, when Ashok Leyland and Tata Motors took 15 percent stakes in the company some people said, “Oh, they are big players and they will swallow us.” I did not think so. When we made people branch managers, we gave them total freedom to decide on the quantum of money to lend and the risk mitigation steps. I shared my opinion on what I thought, but the decision was theirs. We have 700 to 800 branch managers, and only one or two didn’t work out. Most people are quite sensible. Till date, my trust has never been betrayed.

High performers get more responsibility

High performers get more responsibility

In any group of 20 to 30 people there will be three or four who will perform better than others. I measure performance objectively. I am a statistician by training and keep subjectivity to a minimum. I ask myself why I consider someone a better performer than others. Once you have identified those people you give them more responsibility.

Your way or my way

When someone who runs a particular business disagrees with me I ask them to run it. I don’t interfere. In one of my early hire-purchase business, there was this person in charge who would take a lot of risks. I decided to bring in an MD from a bank to make sure the business did not take too much risk. The person in charge resisted and said, “You are trying to clip my wings”. I backed off. The business did very well for at least four to five more years.

Profit is only a yardstick

It is never the end goal. The customer always comes first. Profit is simply a way of finding out how well we are serving the community. If you serve the community well you make a higher profit.

Walk the walk

For instance, when we do a fixed deposit mobilisation, the branch manager will not just fix a target for others he will first take a target for himself. So, we never ask our colleagues to do things that we ourselves could not do. When we started our business, it was customary to repossess [take back the vehicle if the loan wasn’t repaid] through an outside agency. We did it ourselves. We would explain to the customer that he wasn’t managing his property well, and that if we took back the vehicle we could minimise his loss.

Private equity works

We have had almost three, four or five private equity firms that have invested in us. We found them to be pretty good. Their direct contribution was good, but more important was they did not try to contribute! One person from TPG who was there in Shriram City Union Finance said after three months, “I don’t see a role for myself here. You are doing your job well. I don’t want to be a nuisance here.” We want private equity partners to make money for their investors. Our business needs capital. If they make money they will support our future ventures too.

Understand risk, not fear it

Risk is a part of business. When I look at the business, I see the possibilities along with the risk. When you see a face you don’t just see the nose. You have to see it in totality. I am aware of risk. Sometimes you don’t know the risk and only when you get into the business you come to know its extent. I am okay with that because I always provide for that unknown in some measure so that I don’t drown.

First Published: Apr 18, 2013, 06:30

Subscribe Now