Samsonite Goes Beyond Metros With Project Pappu

That's the code name for Ramesh Tainwala's plan to sell Samsonite suitcases to small towns. Along the way, he's creating an entirely new business model, thanks to the global partner's policy of local

Deep in Samsonite’s product development centre in Nashik, Maharashtra, the outline of a vast new project is taking shape. It’s a project that has the potential to change the fortunes of the company. If successful, it would significantly accelerate growth in India and could be replicated in other developing markets.

Here’s what Samsonite is up to: The company, which has so far aimed at attracting the urban affluent user, will now also open a second front. It plans to woo the rural and mass market consumer with the help of a cheaper product. Code named Project Pappu, it aims to create a set of luggage options that cost as low as $50 (Rs 2,750). These would sell in places like the neighbourhood furniture store and clothing stores—not the usual places where people buy luggage.

Leading the charge is Ramesh Tainwala, who has a 40 percent stake in the company’s business in India, the Middle East and Africa. He’s also an executive director on the board.

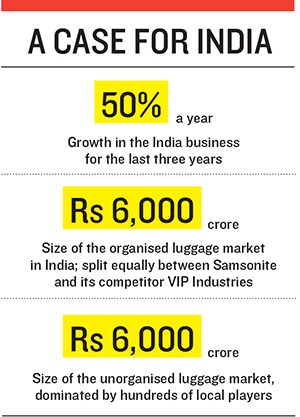

It’s a bold bet, for now Samsonite will be competing with local players that are far more nimble. But Tainwala is confident he’s made his company agile enough to compete with the hundreds of small luggage companies in India.

Tainwala certainly has the credentials to pull it off. In his 15-year-long association with Samsonite, he’s brought the India business to a point where it is the company’s third largest business globally. This financial year it is on track to clock Rs 3,300 crore in revenue. Besides, in 2004, he revamped the sluggish China business in six months. Back then, India, a smaller market, outpaced China. Now China is the company’s second largest market.

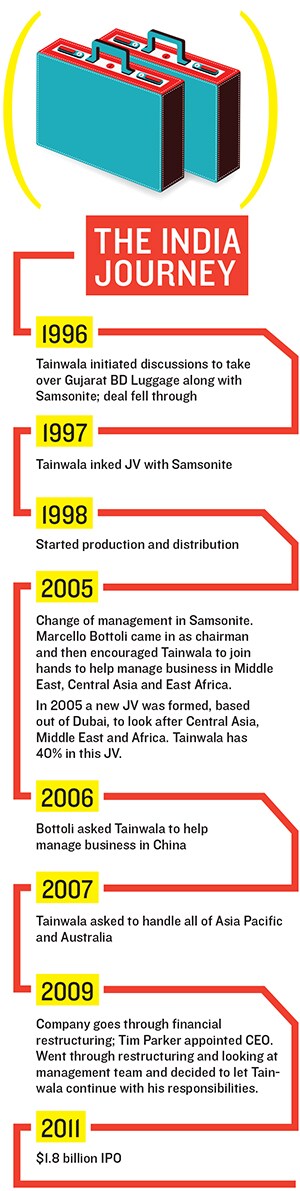

The confidence that the global parent has reposed in him has come after long years of struggle for the two joint venture partners. It’s something not many survive. Some part ways in some cases one partner buys the other out. Either way, there is a lot of heartburn as the business reorients itself post-partnership.

Tainwala concedes that he’s had his fair share of disappointments. “For the first seven years in India, our revenue was less than the salaries we paid,” he says. But things changed quickly. Case in point: Global headquarters wouldn’t let him sell black as it believed Indians considered it an inauspicious colour. Now black accounts for over half of India sales.

So how did Tainwala establish that relationship of trust with a company that has seen three CEO changes in the past decade? How did he manage to rise to the top of a company that went through financial difficulties in 2009 and yet successfully listed in 2011?  Building Trust

Building Trust

In 1997 when Tainwala teamed up with Samsonite, he had just a rudimentary understanding of the luggage market. A graduate from Birla Institute of Technology and Science, Pilani, he had been rejected for a job with VIP Industries and had gone to work setting up his own business. One of the companies, Tainwala Chemicals, supplied the plastic sheets that were moulded into suitcases to VIP Industries. When Samsonite came calling in India, he tied up with them.

Like all partnership agreements, the partners had their rights and responsibilities clearly explained. It was assumed that if they stuck to the script everything would work smoothly.

But Tainwala, who operates from a spotless desk in his Mumbai office, was in a bind. As he explains in his folksy style, he’d invested a tidy sum in the facility to make suitcases in Nashik. But the plastic sheet facility was in Silvassa, 4 hours away. The sheets, being hydroscopic in nature, absorbed moisture and were unusable by the time they reached Nashik. Since Tainwala owned both, the ball was in his court. If he asked for financial help to move the factory closer to Nashik, the matter would have gone all the way to the headquarters, leading to a three-month delay.

So Tainwala took matters into his hands. He moved the factory to Nashik at considerable cost and the matter was resolved.

In 2000, it was Samsonite’s turn to reciprocate. The Nashik facility only produced for orders in the Indian market. Those orders were not sufficient to keep the plant running the entire month. As a result, due to the periodic shut downs, quality suffered.

Luke Mansfield, the then CEO of Samsonite, decided that the Nashik plant would supply to Germany. While there was a lot of opposition from German sales staff and the landed cost of the luggage (the total cost including shipping) was twice as high as the Belgium manufacturing plant’s, the company knew that it had to do this in order to support the Indian business. Again, as Tainwala explains, they didn’t have to do it but they did it and once again showed, “that we don’t think like partners and stick to what is laid out in the agreement. We just do what’s best for the business and the rest follows.”  Fixing the China Business

Fixing the China Business

A few years later in 2004, Samsonite changed hands and Marcello Bottoli, a former Louis Vuitton CEO, took over. One of his key concerns was to figure why the Chinese business had not been performing.

As millions of Chinese travelled for the first time, the luggage industry in China was doubling every year. But in Samsonite’s scheme of things, the business at $30 million (Rs 150 crore) was chicken feed.

What confounded Bottoli was that the Indian and Chinese joint ventures had been signed at the same time in 1997. India, a smaller market, had outpaced China. Bottoli knew that something radical had to be done, outside of the existing company structure, to fix this. He reached out to Tainwala, who agreed to work as an advisor for six months.

First, Tainwala found that just like in India, which had VIP and Aristocrat, there were strong competitors, like Crown, in China. But instead of putting people who understood the ground realities, Samsonite had an over managed business where 10 expats who knew nothing about the market took decisions.

“At times it seems as if the locals had to take permission to even visit the toilet,” he says. Clearly out of sync with what was needed, they took wrong decisions on pricing, positioning and strategy. While local competitors took two months to bring out a new product, Samsonite took six. “Even product codes had to be approved from Denver, Colorado, where the company was founded a century ago,” says Tainwala.

Over the next six months he visited stores across China, asking only two questions: What sells and what doesn’t? Next came a ban on expats visiting China without Tainwala’s permission. In order to reduce the time it takes to get permissions, Tainwala got an ‘underground’ testing lab set up.

Here luggage designs and specifications could be approved within weeks. Their time to market dropped to two months. New colours were experimented with. Styles changed. Sales picked up and China is now the company’s second largest market.

A Local Push

While Asia had turned around thanks to Tainwala, the company had floundered in Europe and America. Bottoli who came from Louis Vuitton had tried to sell the brand as a luxury product, driving consumers away. By 2009, the company was in a financial mess and Tim Parker, a well respected manager who had turned around Clarks Shoes, was brought in.

Among the first points Tainwala made to Parker was that local units need to be given autonomy to decide on products and sales. At the same time the company commissioned Boston Consulting Group for a SWOT analysis. Their conclusion: In trying to be all things to all people the company had products that couldn’t succeed in any market.

At the end of the conversation, Parker says, “I began to question the need for a centralised headquarter.” He dismantled the company’s corporate office and gave each region independent charge.

Here’s how it works: From being a company operating out of London, Samsonite has adopted a federal structure. Each region is free to decide on what products they need and how they want to sell them. Samsonite’s regions operate independently with quality being the only function that has been kept centralised.

Take design. The company now has eight global design centres where designers work on products that are then put on the company intranet. Managers in each country choose what would work for them and order accordingly. In Asia that translates into small handles, as Asians have small hands. In the Middle East that translates into bigger ‘boxier’ bags that are one-and-a-half times the size of the average Samsonite bag. This has also helped the company cut down on its lead times. Now products can move from design to markets in under three months.

Parker says that working in such a federal structure has been extremely liberating for his managers. In effect, he says, costs have increased marginally as people are always travelling. “The way the model works is that we give an incredible amount of responsibility to our people. If they have an issue they raise their hand. Short of that we just don’t interfere,” says Parker.

The New Plan in India

Back in India, with the company growing at over 50 percent a year for the last three years, Tainwala knew the time was ripe for him to try out a concept that had the potential to accelerate growth further. And now, in the new Samsonite, he could experiment and sell it any way he liked as long as it met the quality test.

In 2011 Tainwala came up with a whole new business model that re-looks at cost, design and distribution.

Project Pappu has the company working on products for consumers in smaller towns—those too intimidated to enter large stores. Tainwala explains that as of now luggage is made using either blow technology or wrap around technology. The new range will be made using something completely different, he says, declining to elaborate.

The first bags, which are expected to roll out this summer, will target customers in smaller towns and cities. You won’t find these bags in downtown Mumbai but you’ll find them in Bhiwandi and Virar on the edge of the city, says Tainwala. A new distribution model will be put in place. The bags will also be stocked at stores that sell household appliances and corner shops selling bed sheets and pillows.

As suitcases are not a fast moving category, high margins are used to incentivise dealers. Margins as high as 50 percent are not unheard of in the trade and Samsonite’s margins are no different. Now with luggage selling for as little as Rs 2,750 and addressing a larger mass of consumers, the company has seen that it can cut margins to as low as 15-18 percent.

The model, however, does have its share of sceptics. Jagdeep Kapoor of Samsika Consultants says the plan doesn’t make the bags aspirational enough. Then there are those who say Tainwala still won’t be able to match the cost structure of the unorganised sector. And there’s a third lot that points that the needs of low-income buyers are radically different and price plays a much larger role, often the only role, in their decisions.

Tainwala, who spends 20 days a month visiting his stores, believes he knows enough about the consumer for his plan to succeed. For instance, he’ll make sure employees selling these bags don’t talk down to customers. This learning came a few years ago when he discovered that whenever the store manager had his weekly off, sales would shoot up as the other employees in the store did a better job of convincing customers to buy. Their trick: Speak to the customer in his own language. He’s spent time studying reams and reams of data to show there is a market for his new products.

The whole company is watching. It’s Samsonite India’s boldest experiment yet and if it succeeds, the plan is to emulate it in other Asian markets.

For Tainwala, who has been through a time when he had to go to the global headquarters for even changing the colour of the bags he sold, this freedom has come like a breath of fresh air. Under the old regime he would never have been able to experiment, he says.

First Published: Apr 18, 2013, 06:06

Subscribe Now