Can India's $12 billion R&D fund kickstart a revolution?

Experts say what matters most is how the money is spent to build collaborative ecosystems and thriving innovation

A few years ago, Aditya Sharma, the head of process solutions for German multinational Merck Life Sciences, was on a visit to Hyderabad, home to some of the country’s largest pharmaceutical companies.

He happened to visit an incubator, a facility that provides support to early-stage startups, helping them develop their business model prototypes and prepare them for growth. “It was one of the plug-and-play labs," Sharma tells Forbes India.

It is often at these incubators that many of the world’s most renowned startups and billion-dollar companies have been founded, including Airbnb and Dropbox.

Inevitably, that means they also serve as a hub for research and development (R&D), both from a commercial and strategic point of view for a country. Sharma, however, was in for a surprise in Hyderabad. “Some of them [startups] told me that they are not even able to afford the rent, and some had already moved out," he says.

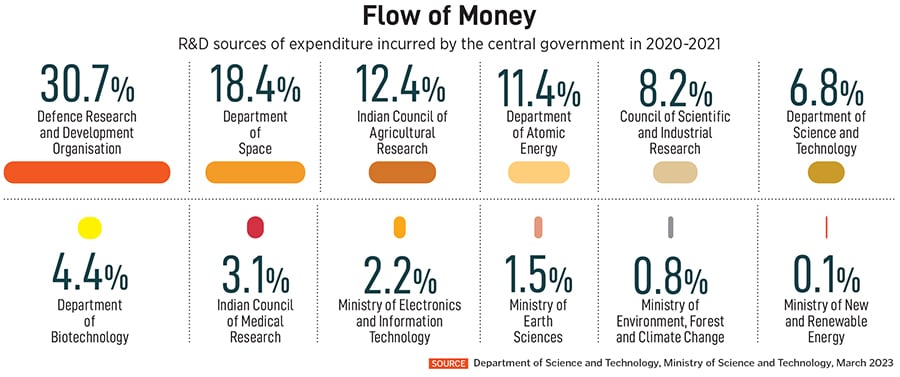

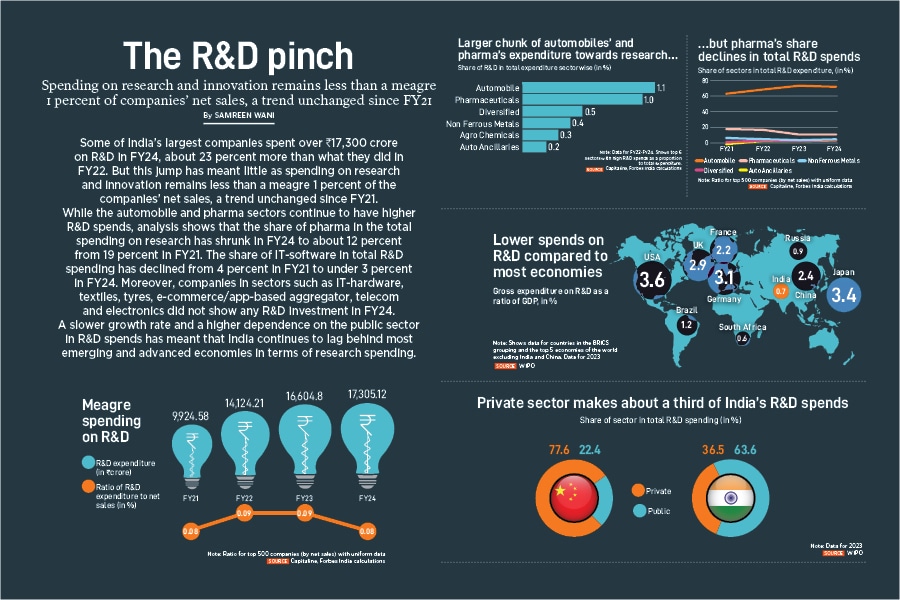

In many ways, that’s also the dark side of India’s R&D story, one where entrepreneurs and scientists often find themselves in despair, having to wind down their work for lack of funds after making early progress. India’s R&D expenditure as a percentage of GDP remains paltry, ranging between 0.6 percent and 0.7 percent, much lower than countries such as China, the US and Israel. Israel, a global startup hub, spends 5.4 percent of its GDP on R&D, while the US, the world’s largest economy, spends 3.5 percent of its GDP.

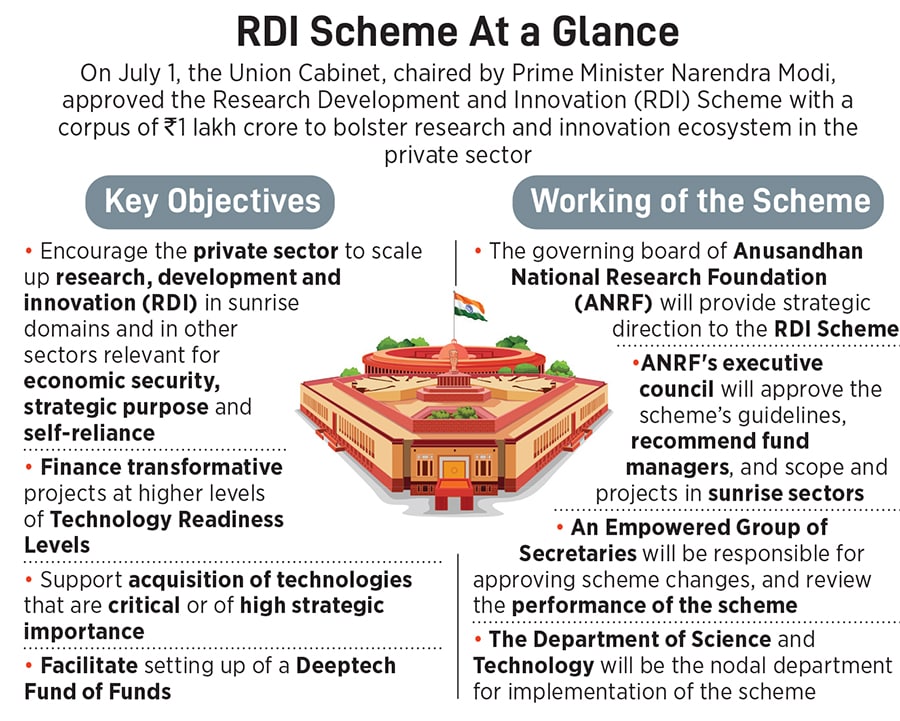

Acknowledging this reality, the Narendra Modi government is attempting a shakeup with a new policy with a staggering corpus of ₹1 lakh crore ($12 billion) to bolster the movement from research to products. The new scheme looks to provide financing or refinancing with long tenors at low or nil interest rates to spur private sector investment in R&D.

“The scheme has been designed to overcome the constraints and challenges in funding of the private sector and seeks to provide growth and risk capital to sunrise and strategic sectors to facilitate innovation, promote adoption of technology and enhance competitiveness," the government said at the time of its launch.

That means, sectors such as energy, deeptech (quantum, robotics, space), agriculture, health, education, biotechnology, pharma, digital economy and strategic technologies, which are critical from a geopolitical point of view, could now find it easier to access funds that have long remained a constraint. The new scheme will also finance transformative projects at higher levels of technology readiness in addition to helping acquire technologies that are critical or of high strategic importance.

India’s Department of Science and Technology will serve as the nodal department, and the scheme will have a two-tiered funding mechanism. At the first level, there will be a special purpose fund (SPF) that will function as the custodian of funds. From there, it will be disbursed to a variety of second-level fund managers, who will disburse the funds in the form of long-term loans at low or nil interest rates. Financing in the form of equity may also be done, especially in the case of startups.

“This landmark investment aligns with our long held belief that only through intensified innovation and private-public partnership can India achieve global leadership," says Anish Shah, CEO of the $25 billion Mahindra Group, which has filed 346 patents in FY25 alone in its automotive business. “Increasing R&D spend is critical to boost scale, encourage risk taking and elevate India’s competitiveness on the world stage."

The government’s urgency to focus on research, development and innovation (RDI) also comes at a time when geopolitical tensions have begun to peak, disrupting supply chains and trade. A case in point is the rare earth magnets, a crucial component in electric vehicle manufacturing, on which China has a near monopoly. A few years ago, a global semiconductor chip shortage had disrupted manufacturing across sectors such as automobiles, computers and household appliances.

“There is huge urgency for a scheme like this," says Amitabh Kant, former CEO of Niti Aayog, the government’s premier think tank. “If you don’t innovate, you lose out to countries like China on various areas of growth. The private sector has not been spending money, and this will catalyse growth."

“At an industry level, this kind of patient capital—long tenor, low-interest funding—can unlock transformative potential across sunrise sectors like clean energy, semiconductors and AI [artificial intelligence]," says Kishor Patil, co-founder, CEO and MD of Pune-based KPIT Technologies. “I’ve long been a proponent of deeptech investments, and this scheme directly addresses the capital gap that often holds back high-TRL [technology readiness level] projects from reaching commercial scale."

While India’s gross expenditure on R&D (GERD) has been consistently increasing over the years—it has more than doubled from ₹60,196.75 crore in 2010-2011 to ₹127,380.96 crore in 2020-2021—its GERD as a percentage of GDP remained at 0.66 percent and 0.64 percent during 2019-20 and 2020-21, respectively. That’s a far cry from India’s oft-compared neighbour China, which spends more than three times that of India at 2.4 percent, according to World Intellectual Property Organisations (WIPO) data.

China had in 2008 launched a scheme to kickstart its R&D investments, through the Thousand Talents Plan (TTP), which included research autonomy, leadership posts, lab funding and generous salaries, as a move to reverse brain drain. However, the difference is that India’s RDI scheme doesn’t aim to bring the diaspora back. Instead, it’s about unlocking domestic capital to fuel innovation within.

Second, China took the top-down route—centrally planned, state-led, with clear political intent—while India’s RDI model leans on the market with a simple logic that if the government funds more R&D, private players will be willing to take bigger risks in sectors such as health tech, semiconductors and green energy, where outcomes are uncertain, and timelines are long.

While China’s TTP worked in some ways by bringing back thousands of high-calibre researchers, making Beijing a serious contender in global tech, it also raised alarms, especially in the US. Some scientists were accused of hiding funding ties to China. That led to investigations, job losses and even criminal charges. By 2022, under pressure both at home and abroad, Beijing quietly retired the original TTP.

The RDI scheme, however, focuses on the growth of R&D initiatives in the private sector, which includes startups and budding companies that are converting into unicorns, providing employment and contributing significantly to the economy’s growth.

“There is a lot of dependency of this scheme on the education institution, towards innovation and entrepreneurship," says V Kamakoti, director of IIT-Madras. “In my opinion, this scheme will become extremely successful. We, as education institutions [government and private universities], understand that there is a fund, and now our job is to pull the startups up."

Today, despite all the growing chorus around the lack of R&D funding, there is also an increasing list of companies that are rewriting the traditional approach to R&D. For instance, Noida-headquartered Addverb Technologies, which has created a 25-plus family of robots, ploughs back more than 25 times the national average into their R&D activities. “The single and most important reason that has contributed to our success and will continue to be is our R&D," says Sangeet Kumar, co-founder and CEO of the robotics company.

With two centres for R&D, in Noida in Uttar Pradesh and Fremont in the US, 25 percent of the company’s revenue (₹600 crore in 2024) is dedicated towards R&D, and 25 percent of their 1,000-plus team works in the domain. Since its launch in 2016, Addverb Technologies has sold 3,000-plus robots across 27 countries.

On July 2, multinational technology company Zoho Corporation launched its AI and robotics R&D centre in Kottarakkara, Kerala. It will be dedicated to enhancing its R&D projects in various fields, starting with AI and robotics. “Our goal remains the same—to develop these capabilities in India and make the country self-reliant in terms of critical technology," says Shailesh Davey, CEO and co-founder. Addverb and Zoho maybe among the few Indian private companies that have consistently invested in R&D, defying a broader trend.

“The Indian private sector has historically been risk-averse in science-led innovation," says professor V Ramgopal Rao, vice chancellor, Birla Institute of Technology & Science (BITS), Pilani. “Many firms find it more viable to import proven technologies than invest in uncertain R&D journeys."

Yet, the landscape, as with the likes of Zoho and Addverb, is undergoing a steady shift. At Addverb, while most of their R&D efforts are funded internally, collaboration with universities abroad as well as in India—such as IIT-Delhi and IIT-Kanpur that receive grants from the government—is also an important aspect.

These premier institutes are building India’s startups, and collaboration with them is crucial not just for research but also for nurturing talent. From Deepinder Goyal of Zomato (IIT-Delhi) and Bhavish Aggarwal of Ola Electric (IIT-Bombay) to Asish Mohapatra of OfBusiness (IIT-Kharagpur), some of these notable founders trace their roots to these institutions.

The reason, as Kamakoti, puts it, is that there is a lot of implicit connection between R&D output with academia. Additionally, Kumar of Addverb believes R&D has come a long way in Indian universities in the past five years, especially in fields such as robotics, drones, space and AI.

There is good reason for that. First, as professors gain the freedom to start their own companies, it helps them understand the needs of the industry and consumers, and invest in R&D accordingly. Second, young professors with PhD degrees from abroad are making valuable contributions. “They are not writing papers that do not have a significant use in the industry anymore. They are looking at real-life problems. There has been a great mindset change," adds Kumar.

Then there are also the growing grants from the government. “I wouldn’t say it’s a great amount compared to the western world, but a significant one from what it was five years ago," Kumar adds.

“As a director, I’m going to tell my students to spend time on entrepreneurship," says Kamakoti. “The next question they will ask is, ‘What is the guarantee that they’ll get funding?’ RDI can give that guarantee. Since the government backs it, eventually it will motivate more people to enter the private sector."

A longstanding trouble has been the lack of industry-academia partnership that often affects the R&D capabilities of the country. “Industry doesn’t always trust academia to deliver on time or at scale. And academia doesn’t always understand what industry needs," says Rao of BITS. “We need intermediaries—translational centres, innovation hubs and startup incubators—that can bridge this trust gap and de-risk the journey for both sides."

“If we talk about the kind of research publications or outputs, India figures in the top three to five countries in the world, especially in the last decade," says Ashutosh Dutt Sharma, CEO of IHFC-Technology Innovation Hub of IIT-Delhi. “However, when it comes to translating the research into something meaningful for society, typically measured by the Innovation Index, we don’t figure even in the top 30 in the world, and that’s a wide gap."

“To truly benefit from the RDI scheme, we must embed research orientation at the undergraduate level with cross-disciplinary projects and real-world problem-solving," says Surajit Das, professor, department of life science, National Institute of Technology-Rourkela. “In India, limited research exposure hinders this growth. To retain top talent, we must offer world-class lab facilities, timely research fellowships, and clearer pathways for academic careers. Encouraging international collaboration, improving mentorship, and redefining research as a viable, rewarding profession will help reduce brain drain and boost indigenous innovation."

Zoho Co-Founders Sridhar Vembu (third from left) and Shailesh Davey (fourth from left) alongwith leadership team at their new R&D campus in Kottarakkara, KeralaImage: Courtesy Zoho

Zoho Co-Founders Sridhar Vembu (third from left) and Shailesh Davey (fourth from left) alongwith leadership team at their new R&D campus in Kottarakkara, KeralaImage: Courtesy Zoho

“This is a timely and bold step, but how the money is spent will matter more than how much is announced," says Rao of BITS.

He says, for it to be effective, the fund must be accessible to startups, MSMEs and academia-led consortia—not just large corporates. Two, the disbursal should be milestone-based and linked to real outcomes such as IPs filed, pilots run and products deployed. It should allow for blended financing—mixing grants, equity and loans. “And most importantly, it must be professionally managed, insulated from bureaucratic delays," says Rao.

“If done right, this fund can become India’s equivalent of the SBIR [Small Business Innovation Research] programme in the US or the TIPS model in Israel, platforms that empowered entire generations of tech ventures," he adds. The SBIR programme provides funding to small businesses for R&D with the potential for commercialisation and spends nearly $2.5 billion a year.

Davey of Zoho Corp feels that for effective translation, identifying areas of critical national importance in terms of capability should be the first step, followed by publishing those areas and inviting Indian companies to participate. The third step should be to benchmark and rank participating companies against their global peers in those respective domains.

“Based on those rankings, R&D grants or loans should be awarded. This process should be transparent. Companies that don’t want to subject themselves to that ranking should not be eligible for the grants," says Davey. However, the bottom line is India needs to invest much more in R&D in the private sector, according to Davey.

“For some critical sectors, the government’s support is needed. Companies that demonstrate a long-term R&D vision and roadmap, and combine it with the ability to execute, stand to benefit the most [from the recently announced fund]," he says.

While the process of disbursal and execution are still in the works, and will be parameters that will decide its success, Kumar of Addverb says the announcement is a welcome move. “Those kinds of investments have still not happened, and this fund will be a game changer, especially for robotics," he says. “And we are in the right position as a nation for the kind of talent we have in software, hardware, AI and our ability to manufacture at scale."

The funds could also lead to the scaling up in the sunrise sector, including energy storage, smart grids, developments in material sciences and so on. “The fund is an interesting development, for it brings together private industry and government in the hope of leveraging each’s strength and expanding R&D scope across key sectors," says Urvi Desai, co-founder of EkoGalaxy, a platform for climate education and wellbeing. “But one needs to question whether critical gaps will be addressed. For example, strong disbursement plans are key to the fund being operational and successful. We will have to wait and see how the guidelines of the scheme are structured and how funds are released," says Shreyas Sridharan, founder, EkoGalaxy.

Faculty head of The Energy Consortium at IIT-Madras, Satyanarayanan Seshadri, says the biggest challenge following the allotment of funds is the time between the announcement and the actual receipt. “You may receive the grant letter, say, six months after you submit the proposal, but there is no real, clear, predictable timeline on when you will actually receive the money," he says. “For a company or a startup that operates on a quarterly basis, it may not work."

The second problem he anticipates is allowing a bit of freedom on procurement policies, because rather than letting companies and entities to focus on research, they have to invest their energies on procurement policies. “You can have sufficient guardrails, but also need freedom to get the best stuff done," he says.

For R&D to succeed in India, three things are critical. Professor Rao of BITS says, first, it is important to draw out mission-driven R&D programmes with clearly defined outcomes like the space or atomic energy sectors in the past. “You can’t leave deeptech entirely to market forces," he says.

Second, having a robust network of translational research centres that sit between academia and industry. “These should focus on design, prototyping and validation, not just publications."

And third, focusing on talent mobility. “We must allow people to move seamlessly between academia, startups and industry. The current silos are outdated. Incentivising joint PhDs, adjunct roles and startup sabbaticals can go a long way in making our ecosystem agile and collaborative."

The foundation may be laid now. But it all comes down to how it will be built up from here now to build India into an R&D powerhouse.

First Published: Aug 04, 2025, 11:24

Subscribe Now