John Grayken: Shadow banker

Secretive John Grayken debuts on the Forbes Billionaires List with the second-biggest fortune in private equity, $6.3 billion. In an era that demonises predatory banking, he's a ruthless, selfish, unp

Practitioners of “distressed investing” are a special Wall Street breed: Bottom-fishers with steel constitutions and a penchant for rushing into fire sales. Like short-sellers, they are often despised because they prey on the weak—companies and individuals who made bad bets or got in over their heads. “Distressed investor” is a sanitised version of less flattering terms from bygone Wall Street eras: Vultures, grave dancers, robber barons.

Among the robber barons of the new millennium, few are as secretive—or as loathed or as successful—as John Grayken of Lone Star Funds. The 59-year-old debuts on the Forbes Billionaires list with a net worth of $6.3 billion, making him the second-wealthiest private equity manager in the world, behind Blackstone’s Stephen Schwarzman. Lone Star has amassed assets of $64 billion, and since its inception in 1995 its 15 funds have logged average annual net returns of 20 percent, without a single year in the red. Schwarzman’s Blackstone, which has assets of $336 billion, has comparable average annual returns of 17 percent.

However, unlike Schwarzman, who employs a small army of professionals to help him and his firm burnish their image through various benevolent causes, Grayken appears to care little about getting good press. You won’t find any libraries or schools or hospitals with his name on them. He hasn’t signed Warren Buffett’s Giving Pledge. And he’s anything but a patriot: In an effort to avoid taxes, he renounced his US citizenship in 1999. You’ll find him on our list as a citizen of Ireland.

Since the Great Recession Grayken has made a specialty of buying up distressed and delinquent home mortgages from government agencies and banks worldwide. He’s also picked up a major payday lender, a Spanish home builder and an Irish hotel chain. Regulators hassle him, and the homeowners whose mortgages he owns or services despise his tactics. In fact, he has become accustomed to taking shots from detractors and has been the subject of protests from New York to Berlin to Seoul. Last year New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman reportedly opened an investigation into Grayken’s heavy-handed mortgage-servicing tactics, including aggressive foreclosures, which have unleashed widespread outcries from homeowners, housing advocates and trade unions.

“There are real questions about the human costs of Lone Star Funds’ business practices,” says Elliott Mallen, a research analyst for Unite Here, a union representing 270,000 hotel and industrial workers.

It’s even doubtful Grayken, who refused to comment for this story, is well liked within his own firm. According to pension fund documents, he is the sole owner of Lone Star and its affiliated asset management firm, Hudson Advisors. Unlike other major private equity firms, which generously share equity among partners, Grayken has a tight grip on his firm’s ownership. While his top employees have become multimillionaire-rich, a number of key lieutenants have departed as Grayken has apparently never valued anyone enough to offer significant ownership in his operation.

The one group that loves Grayken: Pension fund managers, who consider him an alpha god and who happily overlook his sins. “Over the decades John has had phenomenal returns and executed a very disciplined investment strategy—he is in a league of his own,” says Nori Gerardo Lietz, a Harvard Business School professor who ran one of the largest firms that advise pension funds on their private equity investments. “Many of the other real estate and private equity players are really jealous of John Grayken.”

The Oregon Public Employees Retirement System has invested $2.2 billion in many of Lone Star’s funds. In 2013, for example, it committed $180 million in Lone Star Fund VIII and has already posted annualised net returns of 29 percent. A $4.6 billion fund Grayken raised in 2010 has returned 52 percent per year to Oregon pensioners.

With regulators all over the world forcing big banks to deleverage and retreat from various risky businesses, hedge funds and private equity firms like Lone Star have stepped in and are making a killing buying assets from banks on the cheap. Distressed specialists like Grayken, Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital and Leon Black of Apollo Group have become a new powerful class of “shadow” bankers. Among them the most shadowy is John Grayken.

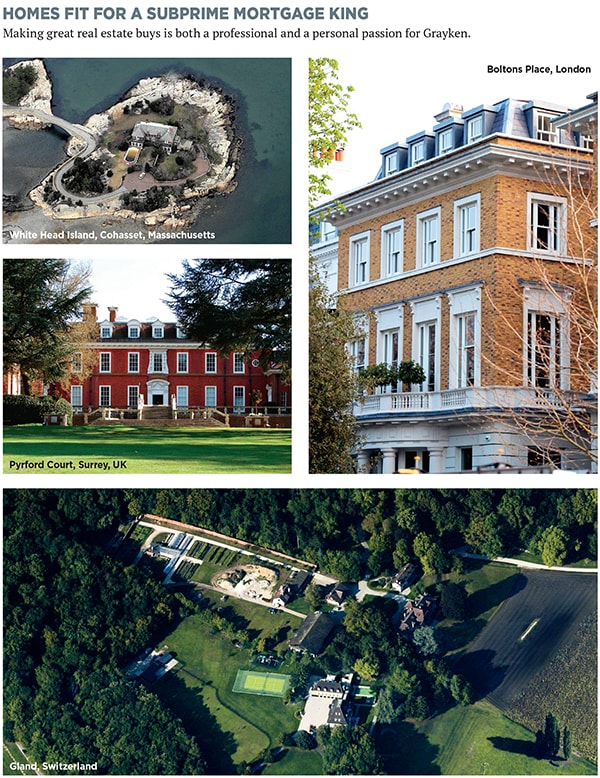

Last year the British tabloids wondered who had purchased one of the UK’s most expensive homes in London’s Chelsea district. The nine-bedroom, nine-bathroom, 17,500-square-foot brick mansion with a glass elevator, basement pool, cinema and Japanese water garden was purchased for $70 million by a Bermuda company. Evidence of the mysterious buyer can be found in a Massachusetts state court, where the home is listed as Grayken’s address in a probate filing. Grayken is also the owner of a 15-bedroom manor house on 20 acres outside of London that was featured in The Omen, a 1976 horror film starring Gregory Peck. Corporate records also show Grayken owning a massive Swiss estate overlooking Lake Geneva.

Though Grayken’s firm is headquartered in Dallas, he lives in London because he can’t spend much more than 120 days a year in the US without having to pay the US taxman. People who know him say he likes to summer close to his family in Cohasset, Massachusetts, the Boston suburb where he was raised. In Cohasset, the small, private White Head Island, which dances in the Atlantic Ocean, cut off from the mainland by a small bridge, belongs to a Bermuda company controlled by Grayken, which purchased it for $16.5 million in two transactions in 2004 and 2007.

Grayken grew up in a less rarefied section of Cohasset, where he excelled at school and on the ice rink. He studied economics at the University of Pennsylvania, where he was a defenseman for the hockey team. In a nifty bit of foreshadowing, he broke the team record for penalty minutes. After Penn he got his MBA from Harvard Business School in 1982 and then landed in investment banking at Morgan Stanley.

Grayken wanted to be a real estate developer and eventually found a job working for Texas billionaire Robert Bass on an office-tower deal in Nashville. The project wasn’t a huge success, but the Tennessee experience cemented Grayken’s relationship with Bass and introduced him to his first wife, a Nashville native.

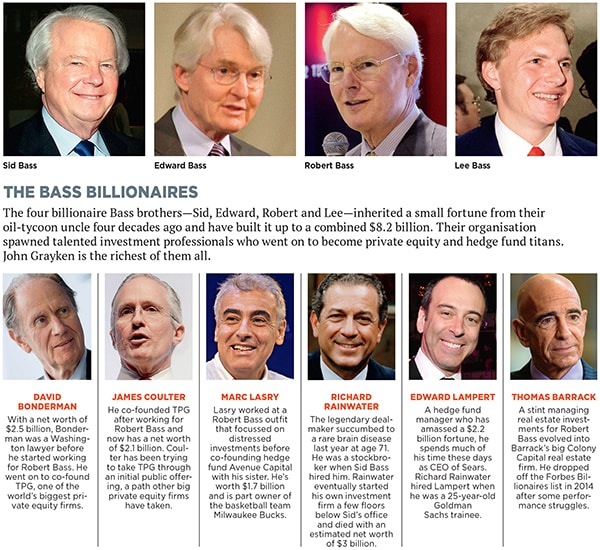

At the time the billionaire Bass brother had been successfully investing his inherited fortune with the help of a talented group of future Wall Street titans that included David Bonderman and Thomas Barrack. These were the days after the junk-bond-fueled S&L crisis, when the government-sanctioned Resolution Trust Corp was liquidating hundreds of failed institutions.

In 1988 one of the largest, American Savings Bank of Stockton, California, caught the eye of Bass, who bought the thrift and with the help of Barrack began selling its assets at a big profit. At Bass’s direction Grayken was dispatched to southern California to join the team and work with Barrack at a Bass affiliate that would become Colony Capital.

Barrack and Grayken did not get along, say people who know both men. Next, Bass put Grayken in charge of a $130 million partnership called Brazos (named after a Texas river where the Bass family is based) that worked with the FDIC to purchase 1,300 “bad bank” assets. Grayken quickly flipped them, making tens of millions of dollars in profits. Bass then backed Grayken in a bigger bad-loan fund, which Grayken transformed into about $160 million in profits. Most of the benefits, however, went to Bass.

When Grayken and Bass couldn’t agree on how to share the profits for the next fund, the duo parted ways in 1996. Grayken stayed in Dallas, raised some $400 million and called his new operation Lone Star Funds. His specialty was buying nonperforming mortgage loans, but he started to originate some mortgages and directly purchase real estate. Starting with Canada, Grayken also ventured into international markets.

Early on he made several strategic decisions that would define his success and differentiate him from competitors. Unlike Colony, Apollo and other opportunity funds that grew out of the S&L crisis and expanded into other areas, Grayken stayed focussed on distressed assets linked to real estate, like delinquent mortgages. When the US economy was doing well, he would set his sights on countries where tough times meant easier pickings. By 1998 Lone Star was in Japan, where ravaged banks preferred selling troubled loans at sharp discounts privately, in order to save face, rather than hold embarrassing public auctions for potentially higher prices. By the end of the 1990s Grayken had moved into troubled European nations like Germany and France.Grayken also developed a reputation as a flipper. The life cycle of his funds is short—investment periods of about three years or less. The assets come in, are worked out and sold. Buying and holding à la Buffett is for suckers, according Grayken’s philosophy. At Lone Star there are no pretenses about longer-term investing or any sentimental attachments to assets, even in cases where more profit can be squeezed out over a few more months or years. Leaving meat on the bone for others is fine. For Grayken the key part of any transaction has always been a cheap purchase price, not any magic that happens afterward. Others can find ways to spruce up assets if they like. “We do our profit on the buy” is how Lone Star’s president, André Collin, described the strategy in a February 2016 meeting. “We do some of the value-add stuff from time to time if it’s there and part of the plan, but if I have an opportunity to sell and I get a good price for my investor, I sell.”

Quick turnarounds work wonders in goosing the all-important internal rates of returns on Lone Star’s funds. Shorter holding periods mean more distributions to investors, who reward Grayken by investing in his next fund. The fees Grayken charges are rich. A typical Lone Star arrangement calls for a fee of between 0.6 and 1 percent of assets under management. Lone Star then keeps 50 percent of all profits once the fund’s return hits 8 percent and until it reaches 20 percent. Beyond 20 percent Lone Star reaps between 20 percent and 25 percent of the profits.

“Grayken, to his credit, has a masterful way of simplifying the process of both buying and selling assets,” says David Hood, who helped found Lone Star and worked there for six years. “He has always bought in volume to create liquidity when it wasn’t otherwise there, and he doesn’t mince words. Just like a hockey player, he is ready to take the gloves off.”

One key aspect of Lone Star’s superior returns: Grayken’s Dallas-based asset management and due diligence arm, Hudson Advisors. Teams at Hudson are responsible for performing full financial analyses and reviews of investment opportunities after Lone Star’s managers have identified them. After a deal closes, Hudson works out and services the loans. It also steps in with legal and accounting help. Hudson now has 865 people, offices around the world and only one client: Lone Star. In the subprime-mortgage business having good data on pools is critical in pricing assets, so Hudson acts as Grayken’s valuable database, giving Lone Star an “edge”. It’s also a backdoor way for Grayken to personally extract extra profits from Lone Star’s hefty asset base. He owns 100 percent of it and charges Lone Star Funds an average annual management fee of 0.55 percent of assets.

While pension managers eagerly await distribution checks from Grayken, tenants and owners of the real estate he sets his sights on dread their new landlord. After he bought the discounted mortgages of 10 apartment buildings in the Washington Heights section of Manhattan from Anglo Irish Bank following the financial crisis, residents flew bedsheets out their windows that said, “Speculators Beware”. When Lone Star started doing deals in Japan, it was locally referred to as part of the hagetaka, or bald hawks. In South Korea Lone Star is known as meoktwi, eat-and-run capital. The German press called Lone Star “the Executioner from Texas” after the firm bought a boatload of nonperforming loans that resulted in homeowner foreclosure proceedings.

Things got hot enough in Germany that Grayken conducted a rare interview with a German publication to explain his side of the story. “No matter where we are active, we adhere to applicable laws,” he said. “Lone Star has no interest to propel someone into insolvency. We prefer when people meet their payment obligations. If not we will take appropriate action.” After the interview Grayken spent $775 million in 2012 to buy TLG Immobilien, an East German owner of 800 buildings held by the government. Within three years Grayken flipped the property for a profit. German politicians argued that taxpayers had been “cheated”.

Germany’s disdain for Grayken is nothing compared with the reputation he has forged in South Korea. In the aftermath of the late-1990s Asian financial crisis, Lone Star bought a controlling share of Korea Exchange Bank (KEB) in 2003 for $1.8 billion. By 2007 Lone Star had received multiple offers for its KEB stake, one as high as $6.4 billion. The deal produced outrage in Seoul, where the perception was that the most painful parts of the Asian financial crisis were the fault of foreign interests. There were legal and regulatory investigations into whether the stock prices of KEB and a separate credit card operation were manipulated downward to enable their discounted purchase. The Korean government blocked the sale, and Lone Star’s man in Korea, Paul Yoo, was convicted of manipulating the stock of the credit card unit and sentenced to three years in jail. To make matters worse, another Lone Star employee in Korea was caught embezzling $11 million from the private equity firm.

Grayken denied any wrongdoing and argued that the Korean government’s actions were arbitrary and discriminatory and ignored Lone Star’s role in rescuing a big bank. Remarkably, Grayken persevered in Korea and ultimately was able to sell his KEB ownership to Hana Financial in 2012, booking a reported $4 billion profit. This, of course, wasn’t enough for Grayken, who is now pursuing arbitration to recover billions more in profits he believes he would have gotten in the original deal.

And if you thought banks behaving badly in America were a thing of the past, Grayken’s Texas mortgage company, Caliber Home Loans, has become infamous for its tactics as a servicer of subprime loans, some dating back to before the financial crisis. Caliber is one of the largest and fastest-growing mortgage companies in the nation, managing more than 325,000 mortgages and worth some $70 billion. A good number of Caliber’s mortgages were purchased by Lone Star Funds at a deep discount—70 cents on the dollar—during auctions held by wards of the state Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and the Department of Housing & Urban Development.

In a stroke of brilliant financial maneuvering Lone Star bundled some of the mortgages into bonds and sold them to investors, immediately booking large profits. At the same time Caliber offered “temporary” loan modifications to distressed borrowers that consisted of five-year interest-only payment plans but failed to offer the homeowners any permanent relief through principal reduction. At the end of the five years these loans would revert back to the original payment terms, with all the deferred payments added in.

“Lone Star has bought these loans at a discount from the government—in effect, they got principal reduction. But they are not passing this benefit on to homeowners or communities,” says Lisa Donner, executive director of Americans for Financial Reform.

Technically speaking, the federal government does not require Grayken’s operation to offer principal reduction, but there has been a roar of voices claiming that Lone Star is abusing the situation. In February the National Housing Resource Center released a survey of nonprofit housing counselors that showed Caliber was the nation’s lowest-rated big servicer and among those doing the “worst job of complying with the servicing rules”. A labour union is accusing Caliber of building a new Countrywide Financial, given that its CEO and top executives are refugees from that hotbed of housing-crisis instigators.

In September the New York Times reported that many of the delinquent mortgages Loan Star bought have ended in foreclosure. Its editorial board went on to accuse Lone Star of relying on the “foreclosure and resale of the homes to make money”. New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman reportedly opened an investigation. Lone Star and Caliber declined to comment.

None of this has slowed Grayken, who has gobbled up $120 billion in assets since the financial crisis, including Home Properties, an apartment REIT in Rochester, New York, for $7.6 billion in October. His latest Lone Star fund is now raising $5 billion trained on real estate in Europe, where banks are still rapidly deleveraging. Grayken has personally invested $250 million in the fund, his 16th, adding to the $1.3 billion he already has invested in Lone Star’s other funds.

His pension clients, including the Employees’ Retirement System of Rhode Island, the New York State Teachers’ Retirement System and Dallas’ Fire & Police Pension System, have yet to make a peep about Grayken’s sleazy subprime mortgage operation. If they have any concern about their American-born Irish golden goose, it’s over Lone Star’s succession and Grayken’s health.

Over the years a parade of talented partners, almost anyone Grayken has ever worked with closely, have left the firm because they either felt shortchanged financially or had disagreements with Grayken. His longtime number two, Ellis Short, who helped found Lone Star, left in 2007. Short did well enough at Lone Star to buy Sunderland, an English Premier League soccer team. The divorce case of another former exec, Randy Work, revealed that he had accumulated a $225 million fortune.

Still, their riches pale in comparison with those of Grayken, who rules with an iron fist and has little tolerance for mistakes. “He felt in many cases that the people beneath him were interchangeable,” says one former top Lone Star manager. (Grayken has also had turnover in his personal life. He divorced his first wife shortly after becoming a tax refugee, changed his mind, got her to take him back within a month of the final divorce decree and then got redivorced six months after that. He eventually married his secretary in London, and the couple have four children.)

Grayken recently flew to South Dakota to visit with a pension client and allay succession fears. As a South Dakota Investment Council member recently put it, “I am concerned about what happens when John passes away. It might just all end.”

But until that happens, the pension funds are happy to deposit more retirement money in the Irish billionaire’s shadow bank. Shortly after the meeting, South Dakota agreed to invest $300 million in Lone Star’s newest investment fund.

First Published: Mar 29, 2016, 07:33

Subscribe Now