K-Pop's big hit gets hit big

The company behind K-pop Sensation BTS is trying to keep Covid-19 from stopping the music

Big Hit excels in its social media strategy, which changed the way all K-Pop bands are marketed. Much of the credit for this strategy goes to Big Hit’s co-CEO Yoon Suk-jun

Big Hit excels in its social media strategy, which changed the way all K-Pop bands are marketed. Much of the credit for this strategy goes to Big Hit’s co-CEO Yoon Suk-jun

Image: Jeon Min Kyu / Forbes Korea[br] This year was meant to be stellar for Seoul-based Big Hit Entertainment. Last year was its best ever, with record sales and profits and an IPO in the works. Then came Covid-19, and with it, the biggest challenge yet to face the company’s founder Bang Si-hyuk.

Big Hit’s rise is almost entirely due to the mega-success of its K-pop group BTS. In 2019, the seven-member act scored three No. 1 albums on the US Billboard 200—the first band to achieve that feat in a quarter of a century. Last July, BTS became Asia’s highest earning band before taxes on the Forbes Celebrity 100 (and the third-highest worldwide). The band’s eight-month Love Yourself World Tour, which ended in October, reportedly pulled in over $196 million.

But now the future of live events—a major revenue driver—is in limbo. As Forbes Asia went to print, all Big Hit concerts were being rescheduled, according to a company spokesperson, and the firm had also stopped selling tickets on its site. Those tickets already sold for Big Hit’s April concerts in South Korea have been refunded the spokesperson says Big Hit is looking to secure new dates and venues.

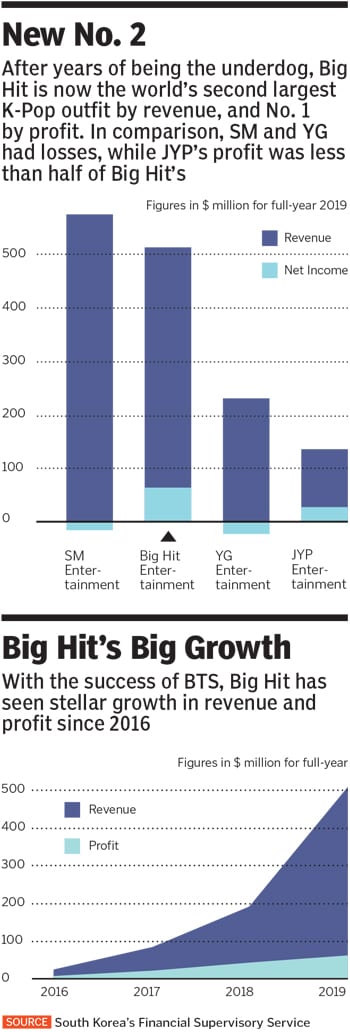

“Big Hit’s business will see a huge impact due to the virus,” says analyst Yoo Sung-man of Hyundai Motor Securities. Last year, Big Hit earned $63 million on a record $507 million in revenue, up more than 160 percent since 2018. But Yoo has slashed his earlier forecast of $616 million revenue this year to a mere $277 million. A spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment on Yoo’s downgrade.

The lack of live events now makes the firm’s digital strategy especially critical. But here is where Big Hit excels—its social media strategy changed the way all K-pop bands, commonly known as idol groups, are marketed, and what arguably turned BTS into a global phenomenon. Much of the credit goes to Big Hit’s 42-year-old co-CEO Yoon Suk-jun, known as Lenzo, who gave a rare interview to Forbes Asia in Seoul prior to the pandemic (Bang and the BTS members declined to be interviewed for this story).Yoon launched BTS’ social media strategy well before the band’s official debut in 2013. The company drew fans to the seven members by opening up their lives on sites such as Twitter and YouTube. Candid videos capturing ordinary moments—rehearsing at the studio, celebrating birthdays, exercising and eating dinner—went on to garner hundreds of millions of views. “BTS were influencers before celebrities knew they had to be influencers,” says Forbes contributor Tamar Herman, who covers international music and who has written a book on BTS, slated for release in August.

An early BTS clip from 2013 shows the band’s leader, who goes by the stage name RM, in a studio at midnight. He says to the camera: “To be honest, I’m cold, I’m hungry and I’m sleepy—I just want to go home.” Videos like these made BTS more relatable to fans. “K-pop fans are multilayered. It’s not that they simply like the music or lyrics. It’s as if they’re dating the artistes,” says Yoon. “We focussed on creating strong content, such as the clips we uploaded on YouTube. Now everyone’s doing it but Big Hit did this seven years ago. We were the pioneers.”

*****

Bang Si-hyuk, nicknamed Hitman, started Big Hit Entertainment in 2005 after working as a composer for JYP Entertainment, one of Korea’s top three music agencies. After a rocky start, Big Hit enjoyed early success with 8Eight, a vocal group trio, and 2AM, a four-member boy band it co-managed with JYP. In 2010, Bang signed BTS’ first member RM, then a 15-year old rapper in Korea’s underground hip-hop scene. Yoon, who became co-CEO with Bang last year, also joined Big Hit in 2010.

Three years later, BTS debuted with its lead single, ‘No More Dream’, a hip-hop number about following your dreams. While the group started to gain popularity, its earlier years weren’t without stumbles. The group’s initial hip-hop image—with Afros, bling and bandanas—didn’t grab mainstream America the way they had hoped. “Some thought they were trying too hard,” says Colette Bennett, a BTS fan and ecommerce editor at US-based site Daily Dot.Big Hit founder Bang Si-hyuk[br]As the group polished its image, songs became catchier and explored issues such as school bullying, mental health, and even politics—a departure from K-pop’s more common themes of love and dancing. “They show so much of themselves to us,” says long-time fan Jiye Kim, 26, a Korean-Australian in Sydney. The group’s social media clout is testament to Yoon’s early insight: BTS’ Twitter account boasts 19 million followers its Instagram 24 million followers. BTS’ YouTube channel has 28 million subscribers, with its most popular music video, ‘DNA’, having been viewed 960 million times. In 2017, BTS won Billboard’s Top Social Artist award, which is based on a vote among fans. The following year BTS made the Forbes 30 Under 30 Asia list.

But Bang, 47, who is also co-CEO, is now grappling with Big Hit’s biggest weakness. “Nearly all of its income is coming from BTS,” says Hyungyong Kim, an equity analyst at Seoul-based eBest Securities. While the “big three” K-pop agencies field dozens of acts, Big Hit has just four.

The firm faces another hurdle: BTS’ oldest member Kim Seok-jin, 27, is due to start South Korea’s mandatory 18-month military service next year. When that happens, Bang and Yoon may launch some members into solo acts—a common practice for agencies that have faced similar transitions. There are some workarounds. “Content can be released while members are in the army, as long as it was clearly produced prior to enlisting,” says Herman. However, all seven members renewed their contract with Big Hit for another seven years late last year. Big Hit’s rise is almost entirely due to the mega-success of K-Pop group BTS

Big Hit’s rise is almost entirely due to the mega-success of K-Pop group BTS

Image: Jose Perez / Bauer-Griffin / GC Images[br]Yoon says BTS’ success is sustainable. “I don’t think artistes lose their market value because of age. Look at U2, they’re old but did they lose value?” he asks. “When the [BTS] artistes reach their 30s, I believe they’ll be able to send a different kind of message that’s relevant to those years. When they reach their 50s, it will be different and so on.”

That said, Bang and Yoon have already started diversifying and expanded the firm’s roster to include a new five-member boy band, Tomorrow X Together. The band is enjoying some early success, landing multiple entries on Billboard’s World Albums chart. In June, Big Hit acquired Seoul-based Source Music, including its six-member girl group GFriend. It has also embarked on a joint venture with CJ E&M—the backers behind the Oscar-winning film Parasite—which aims to field a new K-pop boy band this year.

To find new revenue streams, Big Hit created a tech division that last June launched an app, Weverse, for its global fan base. “The Weverse app presents a lot of opportunities,” says Forbes contributor and Billboard columnist Jeff Benjamin, who covers the K-pop industry. The app, which has 7 million users, sells branded merchandise and monetises concerts and long-form videos. In the community section, artistes can communicate directly with fans. Bang has also been quoted as saying Big Hit can mine Weverse user data for insight. “We created Weverse to maximise communication with fans,” says Yoon.

Still, it’s unclear when BTS and other acts will be able to resume live events—which typically account for 40 percent of a K-pop agency’s revenue (Big Hit says it’s “difficult” to say how much concert tours bring in). One bright spot is China, a major live-event market, which is slowly returning to normal life—at least for now. Then there’s the IPO. Big Hit had reportedly secured underwriters that included JPMorgan in February, and at one point was valued as high as 5 trillion Korean won ($4.1 billion)—which may have made Bang, who owns 45 percent of Big Hit, a billionaire. But with the pandemic and one-seventh of Big Hit’s biggest asset slated for military service, the IPO’s outlook is murky.

Yet Big Hit has beaten the odds against much larger and established rivals. From 2016 to 2019, its sales grew more than 1,500 percent to $507 million, while net income jumped eightfold over the same period. Yoon says Big Hit’s success comes from putting the fans at the centre of its business model. “Good songs are important, but what fans really care about is communicating with their artistes,” he says. “Our fans are everything—I want to emphasise that. We are constantly asking. ‘How can we improve ourselves?’”

First Published: Aug 05, 2020, 11:31

Subscribe Now