Trusts in the age of Trump: Time to re-engineer your estate plan

The federal tax overhaul in the US is spawning new ideas

Image: Viktoe Koen for Forbes

Image: Viktoe Koen for Forbes

The federal tax overhaul just doubled the amount of wealth you can pass to heirs estate-tax-free—without using any trusts or planning gimmicks. Yet rather than looking for a new specialty, top trust lawyers are positively giddy about the opportunities created by the law US President Donald Trump signed three days before Christmas.

The letter of the law allows slightly more than $11 million per person to be passed to kids or other non-charitable heirs free of federal gift or estate tax. But by employing aggressive techniques, New Jersey estate lawyer Martin Shenkman figures, a couple could use their combined $22 million tax exemption to transfer more than a quarter-billion of assets into an irrevocable dynasty trust, where that wealth can continue to grow and pass, estate-tax-free, to an unlimited number of future generations. “This is phenomenal. The numbers are beyond comprehension,” says Shenkman. Is this legally risky? Less so than it used to be. In October, Trump’s Treasury withdrew proposed Obama-era regulations cracking down on certain of these aggressive techniques, which, when done right, have been upheld by the courts.

Adding to the planners’ excitement: The new tax law, with its complexity, hasty drafting and last-minute giveaways, creates new opportunities to use trusts and gifting to reduce income taxes, too.

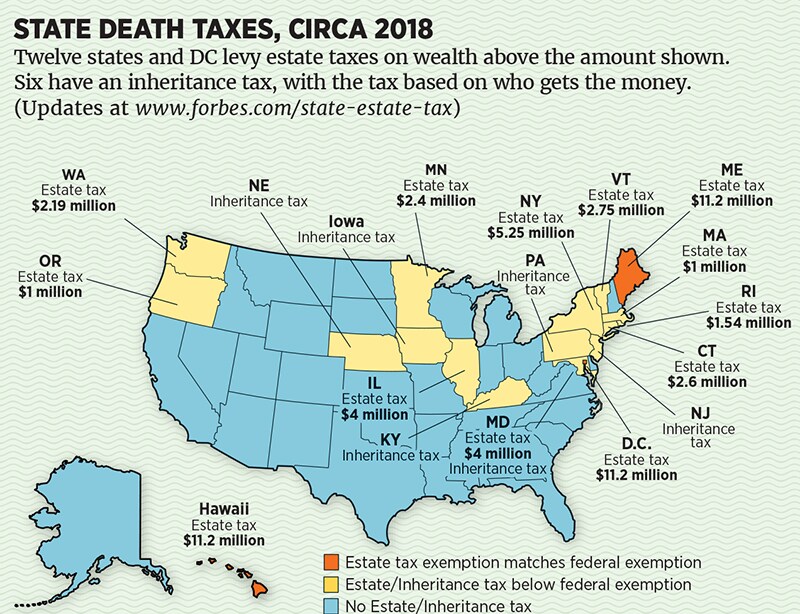

Plus, there’s all the less-cutting-edge—but, if it’s your family, high-priority—legal work the tax changes will generate. Affluent folks should have old trust plans reviewed for booby traps as soon as possible, because they may need to redo or scrap them. Ditto those living in 15 states that impose estate and/or inheritance taxes at much lower levels of wealth than the feds.

One all-too-common trap: A will that establishes a trust linked to an outdated federal and/or state exemption amount. Say a New Yorker has assets in his own name of $11 million. His current will, the one he had drawn up in 2011, when the federal estate-tax exemption was raised to $5 million, leaves the “exemption amount” in a trust for his kids from his first marriage and the rest to his current wife. But if he drops dead now, the kids’ trust would get everything and his wife zip. And since New York exempts only $5.25 million from its own estate tax, accidentally leaving the full $11 million to the kids will incur a $1,226,800 state estate-tax bill. (Amounts left to a citizen spouse are exempt from both federal and state estate taxes.)

“The good news is that these unintended consequences can be fixed,” says Donald Hamburg, a New York City estate lawyer. Infographic: Peter and Maria Hoey for Forbes

Infographic: Peter and Maria Hoey for Forbes

The fix can be as simple as amending your will. In some cases—particularly if there are no second marriages, minor heirs or state estate taxes to worry about—the best fix will be to do away with trusts altogether. That’s because of the “portability” of exemptions between spouses introduced in 2011. Before that change, the wills of affluent couples typically created what’s known as a “credit shelter” or “bypass” trust. When the first spouse (assume it’s the husband) died, an amount equal to his estate-tax exemption went into a trust for his wife and kids. She would have access to trust income and, if need be, principal. But his exemption wouldn’t go to waste. And when she later died, the trust assets wouldn’t be part of her estate. Now, with portability, any unused portion of the husband’s exemption passes to his widow, so long as the executor of the husband’s estate files a tax return electing portability.Why not create a trust anyway? One big reason: Avoiding capital gains tax. When someone dies, the assets in his or her estate get a step-up in basis to their current value, meaning heirs can sell immediately without owing capital gains tax.

But with a bigger $11 million exemption to play with, the lawyers are concocting new techniques that avoid capital gains tax but require trusts. Consider the “mother-in-law trust”: You give your mother-in-law or other older relative a general power of appointment over an irrevocable trust for your spouse and descendants and fund that trust with low-basis assets. When your mother-in-law dies, the assets in the trust get a step-up. True, the trust is now includable in your mother-in-law’s estate. But since she wasn’t rich enough to use her whole $11 million exemption, you’ve expropriated the excess for a good cause: Avoiding capital gains tax.

But why stop with capital gains? Trust lawyers are now busy concocting ways to exploit the law’s new tax break for “qualified business income” (QBI). While there are various restrictions on claiming the break at higher income levels, the provision allows singles with total income of less than $157,500 (and couples below $315,000) to avoid income taxes on 20 percent of their profits from a sole proprietorship, from farming, or from a passthrough, such as a partnership or S corporation. At the last minute, tax writers gave the 20 percent exclusion to trusts with income of less than $157,500 too.

Here’s the ploy cooked up by Las Vegas estate lawyer Steve Oshins. One of his clients is starting a marketing business and figures to earn about $1.6 million a year from it. Oshins suggested he set up eight separate non-grantor trusts for his three kids and five grandkids and give each trust 10 percent of the new business. After the entrepreneur takes a reasonable salary for himself, each trust should be left with about $150,000 a year in passthrough profit. Each of the eight trusts can shield 20 percent of that—or $30,000—from federal income tax, avoiding tax on a total of $240,000. Note that the businessman likely wouldn’t be able to shelter any income if he reported it all on his own tax return, since above the income cutoff, certain service professionals can’t claim the QBI break at all. Expected federal income tax savings from this Rube Goldberg contraption? Nearly $89,000 a year.

And then there are the machinations of legendary trust lawyer Jonathan Blattmachr, now at Peak Trust Co, which sets up Nevada and Alaska trusts for asset protection and tax purposes. He’s scheming to use trusts to get around the new law’s $10,000 cap on deductions for state and local taxes (which, like the doubled estate exemption, technically expires at the end of 2025). Blattmachr figures that by putting his $1.8 million Garden City, New York, home into an LLC, and then putting the LLC shares plus an additional $130,000 of marketable securities into four non-grantor Alaska trusts, he can effectively get a full deduction for the $40,000 in annual property taxes on his home. “Congress can’t contemplate what creative estate planners will come up with,” says a delighted Oshins.

First Published: Mar 21, 2018, 15:27

Subscribe Now