For these wonder kids, the sky is not the limit

The young minds behind KalamSat, the smallest satellite ever built, are not bound by the earth's orbit

(L-R) Sitting: Rifath Shaarook, Srimathy Kesan (mentor) Standing: Gobinath, Yagna Sai, Mohammed Abdul Kashif and Tanishq Dwivedi. Their idea for KalamSat came over a bite of gulab jaamun

Image: P Ravikumar for Forbes India

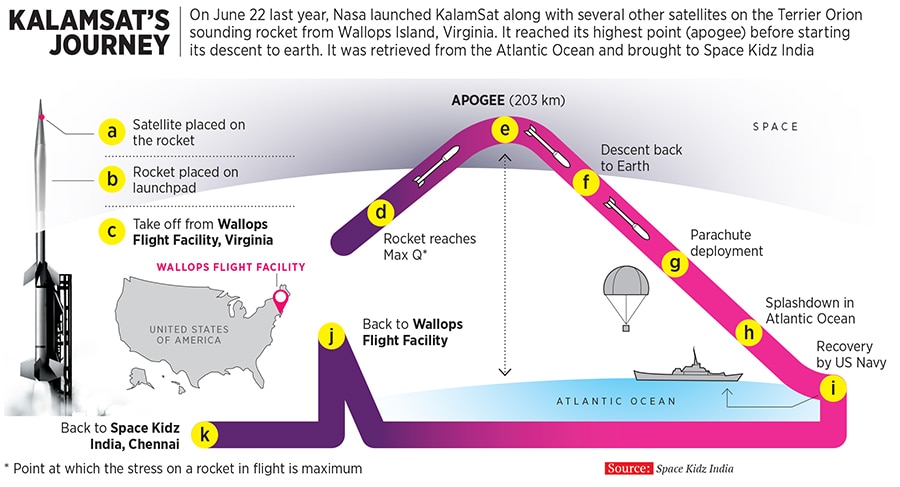

On June 22, 2017, when US space agency Nasa’s Terrier Orion launched into space from Virginia, the rocket carried with it the world’s smallest and lightest satellite: KalamSat. Named after former president the late APJ Abdul Kalam, the 3.8-centimetre, cube-sized satellite weighing 64 grams was built by a seven-member team from Chennai-based Space Kidz India (SKI).

SmallSats and CubeSats are gaining popularity all over the world as they open up space exploration to institutions beyond well-funded government agencies and cash-rich private companies. “KalamSat will lead to more economical satellite launches because once the weight is reduced, the amount you need to pay to the rocket [for the satellite’s launch] will drastically decrease. Smaller satellites are also more eco-friendly,” says Rifath Shaarook, 19, the lead scientist at SKI, who is currently pursuing his undergraduate degree in physics.

Mentored by founder Srimathy Kesan, 43, SKI’s members—Tanishq Dwivedi (flight engineer, 21), Vinay Bharadwaj (structural engineer, 21), Yagna Sai (lead technologist, 21), Mohammed Abdul Kashif (lead engineer, 21) and Gobinath (biologist, 22)—are college students, like Rifath.

“They want to do something unique in life. They are extremely dedicated, with a never-give-up attitude,” says Srimathy about the youngsters, some of whom she handpicked as schoolchildren, and nurtured them to form her core team.

For Rifath and his friends who breathe and eat space research, the eureka moment to build KalamSat came over a bite of gulab jaamun at Srimathy’s home. While the team was confident about overcoming technological challenges, launching the satellite in space would still have been daunting for the bootstrapped firm, with costs breaching $50,000-80,000. Infographics: Sameer Pawar

Infographics: Sameer Pawar

The universe conspired soon as they won a contest by Cubes in Space, a US-based education programme that provides winners an opportunity to design experiments within a 4-centimetre cube, to be launched into space on a Nasa rocket. Team SKI grabbed the opportunity with both hands.

While SmallSat launches are routine, Rifath believes SKI’s pioneering effort is the use of 3D-printed reinforced carbon fibre polymer cube, and packing into it 10 different sensors, a Geiger Müller radiation detection counter, onboard computer, power system, and seeds for agricultural research, in which SKI is involved.

The innovation has reduced the cost of satellite production, which is usually ₹2-10 crore. “With KalamSat, we made a satellite for ₹4-5 lakh. This will give university students and smaller countries access to space so that they can practically engage in research,” Rifath says. That is also the reason why SKI has kept its technology open source, without patenting it. “We want it to motivate students of the future generations,” adds Rifath.

Altruism and adventure aside, space is serious business. A Bank of America Merrill Lynch report released last year predicts the size of the space industry to grow to at least $2.7 trillion in 30 years.

And SKI has already set its sights higher. “In the future, we want to have an ultimate facility in India, where any student from around the world can come and stay and research. I believe in products, and not in projects. When a project converts into products, only then can it help humankind,” says Rifath.

Entrepreneur Harsh Mariwala, who has showcased Aerobotics7’s Harshwardhan Zala and the scientists at SKI through his not-for-profit Marico Innovation Foundation, is impressed with the youngsters’ perseverance and conviction. “Considering they have access to limited resources and mentorship, it is commendable how they have managed to go beyond the development/prototype stage to prove the mettle of their innovation. These young innovators have successfully demonstrated proof of concept,” he says.

The sky, or rather space, is the limit for such impressionable minds.

First Published: Apr 27, 2018, 12:26

Subscribe Now