Strings of santoor: From legend to legacy

The santoor resonates in dual tones, blending percussion with strings, composing melodies that range from folk to classical

Under a starlit sky, in a quiet reverberation at Woods at Sasan in Gir, a retreat surrounded by a 16-acre mango orchard, it was not the rustle of mango leaves nor the breeze"s soft hum, but the santoor"s sacred strain, from mango wood, that strummed. In a mesmerising display of musical prowess, 29-year-old Shahrukh Kawa, hailing from the venerable Sikar gharana, held the audience spellbound as he deftly manoeuvred his fingers across the instrument, unleashing a cascade of classical melodies that transported me on a three-hour journey of sonic bliss.

Shahrukh and his cousin Zubair Kawa on the tabla seamlessly interspersed intricate rhythms and soulful melodies, evoking memories of the legendary jugalbandi between Pandit Shivkumar Sharma and Zakir Hussain. With each resonating note of his classical rendition, the essence of tradition was resurrected that transported me on a nostalgic trip, a memory frozen in time.

Shahrukh Kawa is one of the youngest Santoor players from the Sikar Gharana in Rajasthan. Image: Shahrukh Kawa

Witnessing Kawa’s mastery of the santoor from the soulful Raag Pratiksha to Raag Basant ignited my curiosity about its history. The santoor may seem like a modern instrument, but it boasts an ancient lineage. The word ‘santoor’ itself is Farsi for ‘hundred strings’ but unlike its cousins the sitar and sarangi, the santoor relies on neither plucking nor bowing for sound. Instead, it uses mallets, similar to a piano, for a unique approach to sound generation.

There is also, Kawa points out, in the playing of the santoor, a deeply personal essence, characterised by improvisational techniques such as alap. “Variations in tone are achieved by striking the strings closer or farther from the bridges on each side, as well as adjusting the grip on the mallets. Much of the performance is open to the musician"s interpretation," he says.

The journey of the santoor, from the picturesque snow valleys of Kashmir to the national stage is another tale steeped in substance, at the heart of which lies a one-man odyssey. That of Pandit Shivkumar Sharma, who is credited with the introduction of the santoor to the Indian musical landscape.

“The santoor"s legacy spans merely seven decades," says Padmashri recipient Pandit Satish Vyas, an esteemed senior disciple of Pandit Sharma. “The instrument remained relatively obscure throughout the 1960s and 1970s until a young Pandit Shivkumar Sharma, breathed new life into it." Though his father, a scion of the Banaras gharana, introduced him to music, it was during his job posting in Jammu that Sharma developed a passion for the santoor. In 1955, the 17-year-old ventured to Bombay to participate in the prestigious "Kal Ke Kalakar Sammelan" organised by Sur Singar Samsad. Taking the stage with the unfamiliar santoor alongside a tabla, he surprised everyone by winning both first prizes.

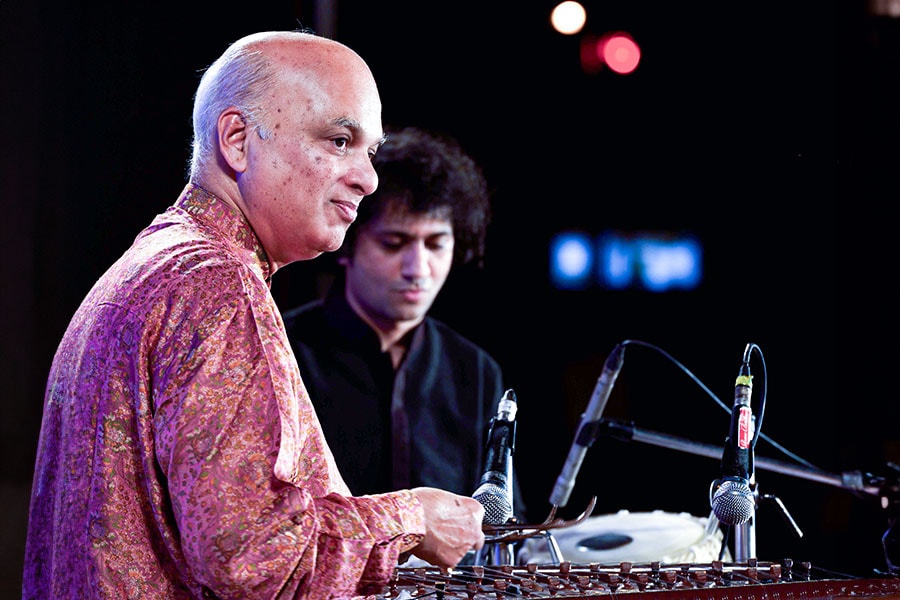

Pandit Satish Vyas, honored with the Padma Shri and Tansen Samman, is one of India"s most renowned Santoor players. Image: Anshuman Poyrekar/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

During the event, Sharma met Pandit Jasraj, a budding musician who was dating Madhura, daughter of filmmaker V Shantaram. Impressed by Sharma"s santoor performance, Madhura informed her father, leading to Sharma"s invitation to Bombay a year later for Vasant Desai"s film Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baje. The film"s soundtrack, featuring the santoor prominently, brought the instrument into Indian cinema"s spotlight and public consciousness.

But there was still resistance from fellow musicians about the place of the santoor in Indian classical music. “When Pandit Sharma returned to Jammu, he diligently modified the instrument, ensuring its compatibility with the nuances of Indian classical music. He proceeded to develop his own baj (style)," says Pandit Vyas.

The santoor is traditionally associated with the sacchetto style in classical music and conveying the emotional essence of the raga, known as raag bhaav, is paramount. “Pandit Sharma developed a technique to accentuate and evoke the emotive depth of classical music during alap and other improvisational passages," says Vyas.

Pandit Vyas underscores the rigorous practice required for mastering ragas on the santoor, emphasising its percussive nature and the necessity of coordinating both hands for ascending and descending notes. Each raga demands dedicated practice to ensure precision and adherence to its scientific structure. “Take, for example, the revered Raga Yaman, where even slight deviations in the sequence of notes can alter its essence." He also elucidates on the complexity of ‘Vakra Ragas’, which require additional practice due to their intricate patterns.

Pandit Shivkumar Sharma, he says, was particularly known for his command over dhuns, including the lively Pahadi dhuns, influenced by his upbringing in Jammu. He also highlights Pandit Sharma"s proficiency in playing thumris, traditionally sung by vocalists, which when rendered instrumentally, are referred to as dhuns.

On the other hand, Gokhale reveals his affinity for ragas like Yaman, Ahir Bhairav, Bimpalasi, Jhinjhoti, Madhuvanti, and Rageshwari. He says, “Another raga closely associated with this instrument is Kirwani, a timeless favourite among maestros like Pandit Satish Vyas." He also highlights the enchanting fusion that occurs when South Indian ragas like Hansadhwani and Basant Mukhari are adapted to the santoor in the Hindustani style, creating a magnetic blend of Carnatic and Hindustani flavours. Kirwani itself, he notes, originally hails from the Carnatic tradition but has garnered immense popularity within the Hindustani repertoire.

Traditionally, the Kashmiri santoor comprised a blend of three kinds of wood: Pine (white spruce or white cedar), walnut, and rosewood. Though solid oak wood is traditional, Kashmir plywood was also used for soundboards, though this practice has waned with the decline of Srinagar"s significance in santoor production. Subsequently, from a folk instrument known as Sufiyana Mausiqi in Kashmir, which predominantly used copper and bronze wires, the santoor has transitioned to its integration into Indian classical music.

"Various kinds of wood like walnut, sheesham, and pine are used in santoor making, but walnut is highly prized," says Shantanu Gokhale (32), the youngest disciple of Pandit Shivkumar Sharma, from Pune. He adds that the shift to cast steel strings, sourced predominantly from Germany, despite being termed “piano wire", are prone to rust as cast steel isn"t stainless. It also requires meticulous care. “Even a single scratch can compromise its integrity. To ensure longevity, practitioners should protect the santoor from moisture and extreme temperatures, maintaining a stable, sheltered environment," says Kawa.

Due to the premium quality wood and the inclusion of 100 steel wires, santoor prices tend to be on the higher end, rendering it less accessible to many. Gokhale says a professional-grade sheesham santoor typically costs around 1.5 lakh, while entry-level options are available at about Rs 50,000. Prominent santoor manufacturers include Hari Bhau Vishwanath in Bombay, as well as others in Delhi and Calcutta.

There have been other changes in the santoor’s journey, being meticulously calibrated to enhance tonal quality and emotional resonance. While Pandit Sharma’s modified santoor was quite different from the 100-string Vana, Pandit Vyas also points to his own instrument—an 84-string santoor from Srinagar, received as a gift in 1976, with intricate modifications made by the legendary musician himself, such as the 29 bridges and specific string configurations.

"While many are taking up the santoor these days, not everyone pursues it professionally, and proper technique can only be acquired under the tutelage of a guru," adds Gokhale. But he is optimistic. "Contrary to perceptions, the allure of the santoor is far from fading. In comparison to instruments like the sitar, sarod, or tabla, which have enjoyed prominence for centuries, the santoor’s journey is relatively recent. Despite this, it has firmly established its presence alongside these classical stalwarts in Indian classical conferences over the past 70 years." He persists, "Initially, there was only one santoor player, but over seven decades, the tradition has seen the emergence of five generations of santoor players."

Shantanu Gokhale, Santoor maestro says the santoor is not just an instrument for us, it"s a living entity that communicates with us. Image: Shantanu Gokhale

Gokhale illustrates this progression with the example of Rahul Sharma (son of Pandit Shivkumar Sharma), who has not only expanded the santoor’s repertoire into other musical genres but has also elevated the instrument to international acclaim. He highlights the continuation of this lineage with the mention of his son, Abhinav Sharma, who at the age of 10 has already begun his musical journey under the tutelage of his father. Pandit Vyas concurs: “We are witnessing the golden era of the santoor."

Gokhale also highlights the santoor’s warm reception among audiences, noting its popularity among his generation, even within classical music circles. He underscores the instrument"s persona, particularly its natural elements reminiscent of soothing waterfalls, which deeply resonates with audiences, fostering a profound bond. Gokhale expresses confidence in the santoor"s future, arguing that its emotional essence cannot be replicated by artificial intelligence (AI). While acknowledging AI’s role in contemporary electronic music, he maintains that the intimacy and authenticity of Indian classical music, especially in live performances, remain irreplaceable.

An exquisite illustration of Indian classical music is the rarity of Megh Malhar, a raga famed for its alleged ability to evoke rain. The raga, it would seem, lends itself beautifully to the santoor. Recently, a glamorous manifestation of Megh Malhar unfolded through a billboard erected by the renowned brand Taj Mahal Tea in Vijayawada, a project in which Gokhale has contributed his musical talents, resulting in an advertisement that has secured a place in the Guinness World Records. Named Megh Santoor, the billboard displays the instrument being played with wooden hammers amidst rain showers, echoing the serene melody of Megh Malhar. Kawa too recounts an experience during a performance of the Megh Malhar raga at an event when, to his surprise, rain began to pour just 30 minutes into the rendition, despite previously clear skies above.

The enchanting melodies of ragas like Megh Malhar flow effortlessly from the santoor, but a dwindling number of professional players casts a shadow over the instrument"s future. Nevertheless, Gokhale is undaunted. “The santoor is not just an instrument for us, it"s a living entity that communicates with us."

First Published: May 18, 2024, 10:38

Subscribe Now