Dasra has changed the face of giving in India

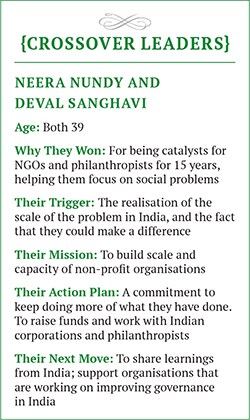

Deval Sanghavi and Neera Nundy ditched lucrative jobs in the US to steer philanthropic initiatives in India in the right direction

Philanthropy isn’t new to Lynne and Peter Smitham. Neither are quality management practices.

Peter, chairman of private equity firm Actis, leads the board of The Atlantic Philanthropies, a foundation that has made grants of over $6.5 billion, drawing from an endowment made by US billionaire Chuck Feeney. Lynne is a management development consultant.

So, they didn’t want any half measures while supporting a constituency close to their hearts: Adolescent girls in India, a largely neglected group vulnerable to early marriage, violence and unemployment. The group accounts for nearly 11 percent of the Indian population, yet remains invisible.

In 2010, the Smithams commissioned a study to map women’s empowerment among poor communities in eight backward states. The report aimed to identify states/regions most in need of support. The study identified Bihar, Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh, where organisations working in these areas received little support. The Smithams had set up the Kiawah Trust to fund projects focussed on girls in India and sub-Saharan Africa (but they wanted to ensure they had the right local partners).

During a two-week trip to India in early 2012, the Smithams were hosted by Deval Sanghavi and Neera Nundy, a young couple who stood out for their approach to solving social problems. The two were founders of Dasra, an NGO they had started with the hope of changing the face of giving in India. “In the two weeks we spent with them from morning to night, we travelled to projects on dusty roads and in smelly slums. We met with their people and started to understand how they worked,’’ recalls Peter. “They were not just raising funds for other NGOs, but more significantly, they were helping them think strategically and scale up.”

SHOWING THE WAY

In many ways, Deval and Neera spoke the same language as the Smithams. The couple had started their careers in investment banking in the US. In 1999, Deval quit his job at Morgan Stanley when he realised his true calling: Working with the underprivileged in India. Neera, who has a degree from Harvard Business School, joined him in 2003.

When they set up Dasra, it was more like a philanthropy fund. Over the years, the founders have played a pivotal role in incubating and scaling up organisations. Impressed by their approach, the Smithams urged them to create a separate unit within Dasra—focussed on adolescent girls—which they would fund. It was set up in 2012 and, in March 2013, it grew to become a full-fledged five-year initiative called the Dasra Girl Alliance.

Soon, Deval got USAID (US Agency for International Development) to join the alliance. This was the first time the US government agency had funded a private initiative. In March 2014, the project got another boost when the Piramal Foundation, the philanthropic arm of the Piramal group, committed funds to it. Having built up scale, they will now direct a funding of Rs 150 crore to empower adolescent girls, mothers and children. The target is to change the lives of one million girls by 2018.

Deval and Neera’s work has been on two fronts: Handholding NGOs to achieve scale and sustainability, and working with philanthropists to help them understand a problem and solve it. “When we started off, our focus was more on the impact of our work,” says Deval. “Over time, we realised we had to create a mechanism to get funders involved. The Dasra Giving Circles were born when we were able to get small groups of high networth individuals together. Each circle has 10 members. To find a seat at the table, a member has to commit to giving Rs 10 lakh a year, for at least three years. It is like a peer group helping out with a particular social problem.”

The Giving Circles have expanded around the world, and have 85 members. Each Giving Circle supports a cause. For instance, Sneha, a Mumbai NGO working towards improving the health of women and children in slums, is supported by women from Philadelphia, US, who are part of one circle.New Philanthropy Capital, a UK-based philanthropy consulting services entity, voted the programme as one of the top 10 innovations in global philanthropy.

In addition to funding, givers also provide guidance and access to their networks. For instance, in 2010, a Giving Circle began supporting Mumbai-based NGO Muktangan, which works with urban children in poor communities, through a teacher training programme. Muktangan focuses on working with community women with a high level of awareness about local culture and the needs of its children.

Over a decade, Muktangan has trained and empowered hundreds of women. Many started out as trainees and moved on to become faculty members in schools. Now, the teachers contribute as much as 40 percent of their household incomes, thus gaining a higher socio-economic status within the community.

The 10 givers from this particular circle contributed Rs 30 lakh each, continued to engage with Muktangan by hosting events and forming partnerships, and had raised Rs 9.5 crore more by March 2014. They now hope to increase funding to Rs 26 crore by March 2015. “We may have given birth to Muktangan, but it is thanks to Dasra that it has come of age and become ready to face the educational world,” says Sunil Mehta, founder of Muktangan.

SPREADING WINGS

Much of Dasra’s growth has come in the last five years. The NGO employs 80 people and has committed Rs 220 crore to social organisations since it was founded. “We had to lay off a few people in the early stages—just after the dotcom bust, when our funding from abroad dried up. We have been very cautious about hiring since then,’’ says Neera. In 2011, Omidyar Networks, the philanthropy investment fund of eBay founder Pierre Omidyar, made a $2-million grant to Dasra, giving them the room to hire talent and develop capabilities.

The NGO’s nine-member board has played no small role in helping them grow. “The NGO arena is getting specialised and Dasra’s USP is its knowledge base,” says board member Amit Mukherjee, a Mumbai-based investment banker. “Neera has built up a strong research team. A lot of the fund-raising is built around the reports this team brings out.” Every report turns the spotlight on one issue. It defines the scale of the problem and opportunities for change, and lists organisations that should be funded.

One such beneficiary is the Aangan Trust, an NGO working to build protective institutions for vulnerable children. Aangan was founded by former advertising professional Suparna Gupta in 2002. “Though we have come into their portfolio only this year, Deval and Neera have been helping us at various stages of our evolution,’’ says Gupta. “When we began work in [government-run] rescue homes, they helped me believe that we could be sustainable. Later on, the big challenge was when we were expanding all over India. Scaling up systematically is very important and we needed help on several fronts, including writing a business plan in a way that educates the funder. We worked on this and were showcased in their reports.”

NGOs need a lot of handholding at critical points in their evolution. Several are never able to make the transition and continue to remain small. “To be able to scale up, the founders have to invest time and money in building up capability,’’ says Amit Chandra, managing director of Bain Capital and Forbes India’s 2013 winner of the NextGen Leader in Philanthropy award. “Dasra has been providing high-quality management training to NGOs,’’ he says.

One of Deval and Neera’s strong points is their great international network, Chandra says. They showcase NGOs to foreign funders through Philanthropy Forum, an annual event that brings together NGOs, heads of foundations, corporate CEOs and others. The Forum broke new ground in November by holding a one-day session in New York, which focussed on Indian philanthropy.

Chandra is working with Dasra to find ways to get leaders of NGOs that he supports to a programme at the Harvard Business School. The first such batch of six went to Boston in July, to attend the highly subsidised, residential programme, which HBS is running for 20 years. “Everyone’s expectations from the non-profit world are increasing rapidly, but little investment is being made in the people who will actually do it. People are still focussed on operations. The scaling up from Rs 2 crore to Rs 20 crore is not happening and we would like to see much more of that,” says Deval.

RETURN TO BASICS

In 2014, Dasra published seven research reports. In the past, these were available only to funders. But they can now be accessed on their website. “A key inflexion point was when we opened up our reports to the public,’’ says Deval. In many ways, he and Neera have leveraged the reports to educate philanthropists.

A report that got much attention this year was titled Power of Play—Sport for Development in India. It features social organisations that are using sport as a tool to improve learning and foster gender equality. Delhi-based NGO Naz Foundation was chosen for a programme that seeks to empower underprivileged girls in the 12 to 20 age group, using the team sport of netball. Dasra has supported Naz Foundation to draw up a three-year business plan that will allow the programme to expand its reach from 9,000 girls (over the last six years) to 30,000 over the next three years. Naz will also roll out a partner training model that allows them to scale up across the country.

Outlining plans for Dasra’s future, Deval says the NGO will go into more depth on different social issues. The next report (and Giving Circle) will focus on NGOs working to improve governance. “We are looking at the root of the problem. The idea is to focus on work in three areas: Improved accountability [of elected representatives], to promote free, independent media and to improve justice [legislative and regulatory design],” he says.

The idea sparked off after conversations with philanthropist Rohini Nilekani, who is passionate about working in this arena.

Corporate CSR guidelines, which require profit-making companies to invest 2 percent of their net profit to do social good, have opened up a world of funding for NGOs. Some estimates say up to Rs 20,000 crore could flow in every year. But those working in the sector say absorbing even half of this amount could be a huge challenge. Through their work in Dasra, Deval and Neera are working to ensure that this capacity grows.

First Published: Dec 31, 2014, 06:08

Subscribe Now