Modern Black Friday workforce: Postal clerk, influencer, robot

Today's retail industry is powered by a variety of staff employees, gig workers and artificial intelligence, reflecting a change in what shoppers want—lower prices and more convenience

Wall-e, a Bossa Nova robot, docking at it’s charging station at a Walmart in Phillipsburg, N.J., Nov. 14, 2019. Designed by the robotics company Bossa Nova, Wall-E is one of 350 robots at Walmart stores across the country with a purpose to free up employees to interact with customers or focus on other initiatives. (Daniel Dorsa/The New York Times)[br]A postal employee who processes one Amazon return after another. A part-time stockroom clerk who works spotty hours for minimum wage and no health benefits. A social media influencer who pitches products to her 83,000 Instagram followers. A robot that scans the shelves at Walmart.

Wall-e, a Bossa Nova robot, docking at it’s charging station at a Walmart in Phillipsburg, N.J., Nov. 14, 2019. Designed by the robotics company Bossa Nova, Wall-E is one of 350 robots at Walmart stores across the country with a purpose to free up employees to interact with customers or focus on other initiatives. (Daniel Dorsa/The New York Times)[br]A postal employee who processes one Amazon return after another. A part-time stockroom clerk who works spotty hours for minimum wage and no health benefits. A social media influencer who pitches products to her 83,000 Instagram followers. A robot that scans the shelves at Walmart.

Meet America’s retail workforce in 2019. Nearly 5 million people are employed in traditional retail jobs. Many still work in stores, selling stuff, but the reality is that today’s retail industry is powered by a variety of staff employees, gig workers and artificial intelligence.

The changes reflect shifts in what shoppers want — lower prices and more convenience. Shopping, even in stores, now involves technology that is altering the way we interact with sales staff. Here are six stories of modern-day retail work.

The Luggage Salesman: Sterling Lewis — Macy’s, Manhattan

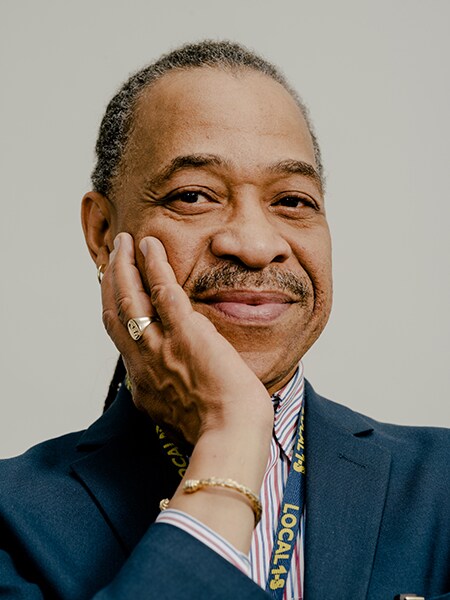

There are not many retail workers left like Sterling Lewis. He started at Macy’s 37 years ago, and he’s still selling luggage in the Herald Square store.

Retailing was not the career Lewis expected to pursue when he moved to Brooklyn from Trinidad at 13. He attended college briefly but dropped out when his son was born and he needed a job. He went to work in the Macy’s stockroom, racking up overtime to support his family. “You do what you have to do,” he said. Sterling Lewis, who works at Macy"s in Manhattan, in New York, Nov. 20, 2019. There are not many retail workers left like Lewis, who started at Macy’s 37 years ago and is still selling luggage in the Herald Square store. (Daniel Dorsa/The New York Times)[br]Today, Lewis earns about $70,000 a year, which includes wages and 2% commissions on each item he sells.

Sterling Lewis, who works at Macy"s in Manhattan, in New York, Nov. 20, 2019. There are not many retail workers left like Lewis, who started at Macy’s 37 years ago and is still selling luggage in the Herald Square store. (Daniel Dorsa/The New York Times)[br]Today, Lewis earns about $70,000 a year, which includes wages and 2% commissions on each item he sells.

Lewis wears a gold hoop earring in each ear and a blue lanyard around his neck to show off his membership in the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, which he credits with providing him and his colleagues with financial security.

Would he ever encourage his 3-year-old grandson to work in a store one day? “Hell no,” Lewis said. “You can’t grow in retail anymore.”

The Robot: Wall-E — Walmart, Phillipsburg, New Jersey

Wall-E starts the day at 4 a.m., rolling through the aisles, scanning the shelves and looking for “outs” — any item that needs restocking.

The robot has a long white neck, bright spotlights and 15 cameras that snap thousands of photos, which are transmitted directly to its colleagues’ hand-held devices, telling them exactly which shelves need restocking.

Designed by robotics company Bossa Nova, Wall-E is one of 350 robots at Walmart stores across the country. Their purpose is to free up employees to interact with customers or focus on other initiatives like Walmart’s push to deliver groceries to customers ordering online. This month, the store in Phillipsburg hired 22 employees, and it is looking to hire 25 more.

Employees have embraced the robot, said Tom McGowan, the store manager, because it performs a tedious task no one likes — cataloging out-of-stock items. (Walmart allows store employees to name each robot. Wall-E wears a name badge like every other worker.)

Customers have different reactions: A few children have tried to ride the robots, while many adults ignore the devices and keep shopping. Some ask whether robots are taking jobs away from humans.

“I tell them, ‘No, I actually have openings,’ ” McGowan said. “ ‘Would you like to apply?’ ”

The Stockroom Worker: Nevin Muni — T.J. Maxx, Queens

For Nevin Muni, life as a part-time worker in a stockroom in Astoria can be unpredictable.

Most weeks, Muni is scheduled to work either 12 or 16 hours, but she is often asked to come in on her days off. Muni, who earns the local minimum wage of $15 an hour, never turns down work. “I have to make ends meet,” she said. “Whatever job I find, I take.”

She has no health insurance but manages to be resourceful. She recently had a cavity filled by dental students at New York University.

Muni moved to New York eight years ago and recently joined the Retail Action Project, a worker group and job training program affiliated with the retail employees union. She has degrees in media economics and human resources management from a university in Turkey. But those skills are not needed in the cramped, windowless stockroom on the third floor of T.J. Maxx, behind the men’s underwear rack and the bin of Christmas-themed pillows.

The Postal Employee: Eric Wilson — post office, Greenwich, Connecticut

Eric Wilson has watched the internet upend how Americans shop and communicate from a unique vantage point: the service window of the post office, where he has worked for more than 30 years.

When Wilson, 58, started in the business, his job revolved around processing letters, cards and flat parcels. But those have fallen off in the age of email and text messages, he said. Now his window is bustling with a specific type of package: returns of online purchases, which have become an enormous part of his days.

“We get hundreds and hundreds of those, especially this time of year,” Wilson, a father of two, said in a telephone interview as he drove to his home in Stamford, Connecticut.

The change is a side effect of the boom in online shopping, which results in far more returns than purchases made at brick-and-mortar stores. It has been a boon for post offices and employees like Wilson.

“At one time, they thought the internet was actually going to kill the Postal Service, but it’s been very helpful because of the way people order packages online now,” he said.

The Influencer: Melea Johnson — Utah

While Melea Johnson doesn’t technically work in retailing, she’s one of the many social media mavens who have become central to the industry by making product pitches to her roughly 83,000 Instagram followers and 355,000 YouTube subscribers. Melea Johnson, who has roughly 83,000 Instagram followers and 355,000 YouTube subscribers, at her home in Utah, Nov. 23, 2019. Throughout November — which Johnson, 37, calls “Black Friday month” — she estimates that she will participate in about 20 sponsored campaigns, in which brands pay her for certain promotional posts. (Daniel Dorsa/The New York Times)[br]Throughout November — which Johnson, 37, calls “Black Friday month” — she estimates that she will participate in about 20 sponsored campaigns, in which brands pay her for certain promotional posts. She also earns commissions from retailers like Best Buy and Target when her followers click on a link she provides and buy an item.

Melea Johnson, who has roughly 83,000 Instagram followers and 355,000 YouTube subscribers, at her home in Utah, Nov. 23, 2019. Throughout November — which Johnson, 37, calls “Black Friday month” — she estimates that she will participate in about 20 sponsored campaigns, in which brands pay her for certain promotional posts. (Daniel Dorsa/The New York Times)[br]Throughout November — which Johnson, 37, calls “Black Friday month” — she estimates that she will participate in about 20 sponsored campaigns, in which brands pay her for certain promotional posts. She also earns commissions from retailers like Best Buy and Target when her followers click on a link she provides and buy an item.

“At this point, what I’ve created has turned into a media and marketing company,” said Johnson, who lives outside Salt Lake City. “I’ve talked to multiple brands who said they don’t spend as much money on TV ads and have put it all into marketing with influencers or online marketing because they just get a bigger return.”

“The people who follow me or watch my stories feel like we’re best friends,” she said. When she recommends a great deal or product they love, “it builds another layer of trust.”

The Quasi-Fulfillment Worker: Sherika McGibbon — Zara, Manhattan

When Sherika McGibbon started working at Zara six years ago, customers seemed to have far more patience.

“Today many people are in a hurry,” McGibbon said. “They don’t take time to touch and feel the material. They just want to buy it and leave.” Sherika McGibbon, who has worked at Zara for six years, in New York, Nov. 24, 2019. “Today many people are in a hurry,” McGibbon said. “They don’t take time to touch and feel the material. They just want to buy it and leave.” (Daniel Dorsa/The New York Times)[br]McGibbon, who has worked all over the retail industry, including at the Gap and the now-defunct Daffy’s, attributes the change to online shopping, which prioritizes convenience over the experience.

Sherika McGibbon, who has worked at Zara for six years, in New York, Nov. 24, 2019. “Today many people are in a hurry,” McGibbon said. “They don’t take time to touch and feel the material. They just want to buy it and leave.” (Daniel Dorsa/The New York Times)[br]McGibbon, who has worked all over the retail industry, including at the Gap and the now-defunct Daffy’s, attributes the change to online shopping, which prioritizes convenience over the experience.

E-commerce has also altered McGibbon’s daily routine and turned her Zara near Union Square into a miniature fulfillment center. McGibbon, who earns about $16 an hour, spends the first part of the morning on the sales floor interacting with customers. After lunch, she reports to the stockroom and packs FedEx boxes until her shift ends at 5 p.m. The delivery service picks up online orders twice a day.

McGibbon, 31, usually packs about 50 such orders a day. During the Black Friday weekend, her store expects to ship 2,000 orders.

A single mother raising a 12-year-old son, McGibbon said she still enjoys the challenge of helping customers put together an outfit. As a hobby, she advises friends and family how to dress. “Stylin’ by Sherika,” she calls her consultancy. She would like to turn it into a business someday.

First Published: Nov 29, 2019, 14:03

Subscribe Now