The curious case of India's inflation

Several entwined factors contribute to keeping inflation high, and an untimely RBI rate cut could jeopardise the fight against it

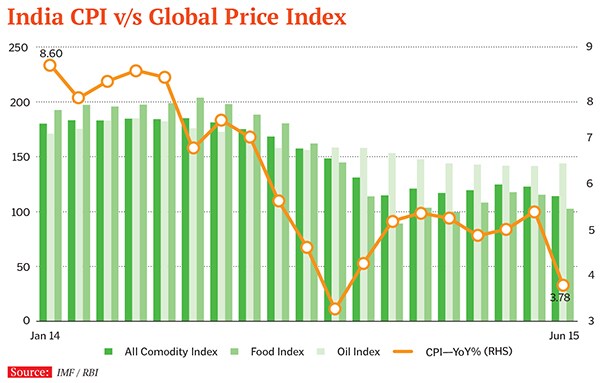

Policymaking at the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has been driven by twin targets—fiscal health and consumer inflation. Even as concerns over the former have receded, the latter has once again been cited as an issue in the third bi-monthly monetary policy statement of August 4, 2015. The RBI has reiterated that rate cuts will commence only when consumer inflation—as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI)—is expected to remain below 6 percent with some degree of confidence. While most experts were prepared for status quo, they are now bracing for the RBI to delay its benevolence to 2016. As if on cue, data released just eight days after the announcement showed that CPI had declined to a new low of 3.78 percent, far below expectations. It again revived flagging sentiment for rate cuts. Is the inflation malaise finally behind us and can we look forward to some magnanimity?

The story so far

The clamour for further rate cuts had been building on the back of falling inflation, fed by globally tumbling prices of oil and commodities. Additionally, as shown in a recent Crisil report, the capacity utilisation in 10 of the top 12 industries in India is at a five-year low, suggesting ample spare capacity in the system. This, combined with improving government finances (again, mostly on the back of lower oil prices, which have reduced the fuel subsidy burden by 70 percent since FY13) prompted the RBI to reduce policy rates by 75 basis points so far in 2015.

Yet, some real concerns persist. While the annual CPI data does show a moderating trend in inflation, the monthly data (especially for year-to-date 2015) is not as one-sided despite further falls in commodity prices: Even as global prices declined 6 percent up to June, prices in India continue to inch higher.  Factors leading to inflation

Factors leading to inflation

Food prices are to blame to some extent: High protein and nutritious items like pulses and milk continue to see high rates of inflation (22 percent and 7 percent, respectively, in June) with rising consumption. So, while food prices have been declining everywhere else, why are they rising at such a fast clip in India? Former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh had famously said high food inflation was the result of people eating better a reasonable response from an economist accustomed to cold facts, but a politically naïve statement in a country where a third of the population starves.

Inflation, however, is not only a function of the growing consumption of more nutritious food items like pulses, meat, fish and eggs (versus cereals), but also of the sorry state of harvesting, transportation and distribution.

Farm output has been growing consistently year-on-year: From 208 million tonnes (mnt) in FY06 to an estimated 265 mnt in FY14, a 3 percent annual growth, compared to a 1.2 percent population growth rate. Hence, food production is clearly not the issue.The issue is wastage.

Between poor farm productivity, bad roads, lack of supply chains and pitiable storage conditions, produce worth Rs 50,000 crore—40 percent of the total—is wasted in the country every year. This is according to a 2013 Parliament statement by then Minister of Agriculture Sharad Pawar. Given the inflation, this figure would have grown by now.

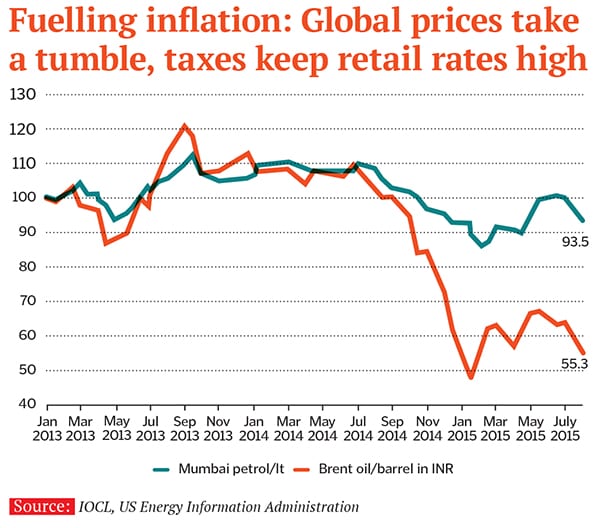

The other major factor is fuel prices, which has a direct and indirect feed into retail inflation. Despite the precipitous slide in global crude oil prices—down 56 percent from beginning of 2013 in US dollar terms, and 45 percent in rupee terms—the retail price of fuel has not come down proportionately.

The cost of petrol before customs duty, excise, state taxes, VAT and cess is just over 50 percent of the pump price. There has been an increase of Rs 7.75 per litre in excise duties between November 2014 and January 2015 levies have gone up in some states and oil manufacturing companies have had a chance to repair their balance sheets through higher margins.

Case in point: BPCL and HPCL have seen huge run-ups in their stock prices (65 percent and 141 percent, respectively) since mid-2014 when local and international prices started diverging. This may be a case of the adage ‘inflation is taxation without legislation’ coming true.

A good question would be: Is local inflation causing oil prices to not fall in tandem with global prices, or is a higher local fuel price itself causing the inflation? A classic chicken-and-egg situation.

Services inflation, too, remains high, mainly due to the health care and education sectors. Low capacity utilisations notwithstanding, multiple supply side constraints contribute to this inflation and, unlike food or fuel prices, there isn’t much chance of it going down.

Consider the various factors of production:

Besides this, the Indian Meteorological Department continues to believe (despite its poor forecasting track record) that a late El Niño will cause the second half of south-west monsoon to be worse than the first. Also, bear in mind that July 2013 and 2014 saw high inflation (9.64 percent and 7.39 percent, respectively), so the base effect has kicked in and brought the headline number—that takes into account all types of inflation—down this month. Put together, these factors have the potential to cause an inflation flare-up.

In any case, one can argue over the real value of rate cuts: a) the relevance of the RBI repo rate for industry, which, after all, is just the rate at which RBI provides bridge-funding to banks b) the futility of rate cuts in a benign demand environment and c) the poor rate of transmission into bank lending rates

These arguments are for another day for now, one would expect RBI to tread the clichéd path of ‘cautious optimism’.

(The writer is an independent consultant and research analyst. Twitter: @cynical_ujval)

First Published: Sep 04, 2015, 06:43

Subscribe Now