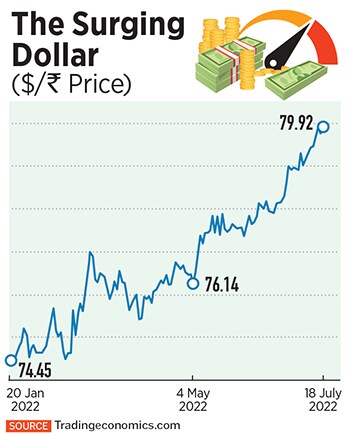

In recent days, sentiment towards the rupee has weakened after it briefly hit a lifetime low against the dollar, at 80 levels, intraday last week. In 2022, the rupee has depreciated around 7.5 percent against the dollar–but it is still less than some Asian currencies such as Thai baht, Korean won and Taiwan dollar. On July 18, the rupee was trading 0.18 percent up against the dollar, at 79.93.

But the constantly fluctuating rupee has meant that importers such as robotics maker CynLr—whose sophisticated components towards robotics are imported—need to be nimble in their financial decisions.

“Whenever we have cash in rupees, but our expenses are global, often in dollars, the immediate thing that we noticed is that our purchasing power is dropping," says Gokul NA and Nikhil Ramaswamy, co-founders of Vyuti Systems, a hi-tech engineering startup in Bengaluru that makes sophisticated computer vision based guidance systems for industrial robotic arms—better known by their brand CynLr.

About 90 percent of the cost of CynLr’s most sophisticated components is pegged to imports, Gokul says. The rest, which are more mechanical in nature, are sourced locally. Imaging sensors, camera components, servo motors, encoders, and robotic arms are all manufactured overseas. “Optics come from France, cameras come from Germany, and a few components from Canada, and all of these international vendors, we pay them in dollars," Ramaswamy tells Forbes India.

Gokul says that the company was hit by a cost of Rs63 lakh in just a week, in terms of materials it could source for its systems, when the rupee depreciated by Rs2 against the dollar. “And there is no means by which we could conserve and lock the price."

He explains that this has affected all their financial decision-making. “Without any anticipation, it’s too volatile, out of our control and it’s very hard for us to balance our costs. I couldn’t have stocked, and this is triggering a huge change in how we can stock things, or the stocking strategy that we can have," Gokul says. “There’s also this apprehension that there will be price increases over the next four years."

The rupee depreciation not only impacts costs, but it is also taxed on the rupee value of its sales, and impacts the market size.

CynLr, for instance, isn’t always selling all its products in the US to try and recover its costs back in dollars. It is also selling to customers locally in India. To them, there’ll be a price increase, and therefore, its market size goes down.

“Now I’m rushing to all my vendors and I’m forced to do bulk orders, but as a startup we are not volume buyers, especially MSMEs, whereas big businesses can leverage their bulk," says Gokul.

![]()

Cells That Matter

Besides AI and robotics, in the electric vehicles (EV) sector, the lithium-ion cells that go into making battery packs are one of the most important components that are fully imported into India, with no local manufacturing. “The same is for microprocessors and other semiconductor components that go into the vehicles, says Amitabh Saran, co-founder and CEO of Altigreen Propulsion Labs, an award-winning electric vehicle startup in Bengaluru that caters to the commercial segment.

“Other than cells, there’s 93 percent domestic value add in our products," Saran says. Cells and microprocessors are among the main components for which Altigreen relies on imports.

As much as 40 percent of an EV can be the battery, and as much as 70 percent of the cost of the battery can be the cells. Then there can be hundreds of semiconductor chips that need to go into EVs, he explains. That means fluctuation in the dollar “will swing it" materially, Saran says.

The government’s incentives under the FAME scheme (Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid & Electric Vehicles) requires indigenisation, which means components have to be sourced in india, Saran explains. But it doesn"t yet stipulate the original source.

Therefore a vendor could have say a motor imported, slightly modify it — changing the external housing, for example — and sell it on as ‘Indian" to an OEM. Going forward the Government of India is planning to mandate that upto 3 levels or tiers of manufacturing has to be in India.

"This will be a game changer whenever it is implemented," Saran says. According to him, these measures are welcome because the industry needs to build these expertise in-house.

In other manufacturing segments too, any kind of integrated circuit will be an imported one. “Considering that IoT (Internet of Things) is going through the roof, even your washing machines will have these semiconductors," Saran points out. Unlike the auto sector, the white goods sector isn’t yet feeling the heat of the supply disruption because currently they use only one or two chips in any given product.

With cars on the other hand, for example, a conventional internal combustion engine-based vehicle that costs upwards of Rs10 lakh will likely have multiple electronics control units or ECUs. And the more sophisticated these get, the more likely that they are imported, Saran says. “So there will be an impact, there’s no doubt about it."

![]() RBI in Battle Suit

RBI in Battle Suit

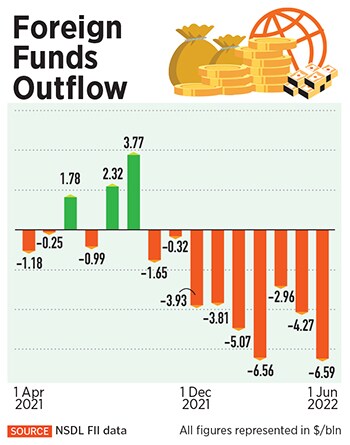

Sustained foreign fund outflows from India have weakened the rupee in recent weeks. Foreign funds have sold Indian equities in excess of Rs2.34 lakh crore in 2022 alone, marking it as possibly the sharpest ever for India (see fund outflows chart). The unrelenting geo-political crisis due to the Russia-Ukraine war, high crude oil prices and monetary policy tightening by several central banks to battle inflation, have all kept the demand for dollars high.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has been doing the protective act by selling dollars periodically.

The RBI has in recent weeks cautiously intervened to support the rupee, particularly as it briefly touched the 80 mark against the dollar. The central bank has not been able to arrest the decline in the rupee because of the dollar that is strengthening rather than the rupee weakening due to a specific reason.

It must also be noted that the rupee has appreciated against the euro, the yen and the pound in the past twelve months. Also, other currencies have depreciated more to the dollar, than the rupee. This can be seen as the dollar index has gained against the euro, British pound, Swiss franc, Canadian dollar and Swedish krona.

Dealers have also been quick to point out that—unlike previous times, such as the 2013’s ‘taper tantrum’ when the rupee depreciated 15 percent—this time the fall has been, so far, less acute and also orderly. The RBI’s observations and commentary relating to the rupee fall have been also restrained, and it has not moved into a panic mode yet.

India, like other emerging markets, was already hit as funds have been pulling out money from equities to take back to their home markets and invest in bonds, eyeing better returns in US 10-year bonds. This trend is likely to continue for some more time, due to high US interest rates and Indian equities not really pulling back from its recent lows, depreciating by around 14 percent from its October 2021 intraday highs of 62,245 levels, despite strong domestic investor buying on each decline.

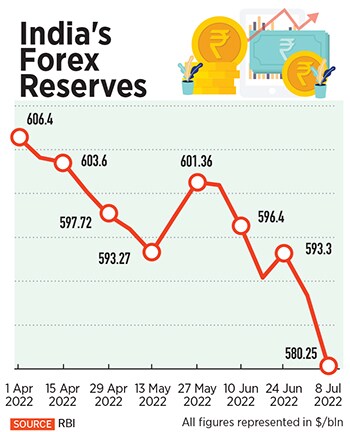

![]() The falling rupee has meant that India’s foreign exchange reserves have also been falling in recent weeks (see forex reserves chart), to $580.2 billion as on July 8, against $606.4 levels at the start of the financial year on April 1, according to RBI data. Economists say this is due to the fall in the foreign currency asset (FCA) levels.

The falling rupee has meant that India’s foreign exchange reserves have also been falling in recent weeks (see forex reserves chart), to $580.2 billion as on July 8, against $606.4 levels at the start of the financial year on April 1, according to RBI data. Economists say this is due to the fall in the foreign currency asset (FCA) levels.

The RBI has a very sensible policy towards the rupee: It is not there to defend a particular level but only to take care of volatility.

"The RBI is already in its battle suit. The wheels are in motion as policymakers have introduced measures aimed at encouraging capital inflows and curbing imports. The RBI is maintaining a fine balance: By letting the currency float, but also intervening judiciously when it deems the rupee is excessively volatile," Aurodeep Nandi, India economist and vice president, Nomura tells Forbes India.

Nomura forecasts the rupee to touch the 82 levels by the September-ended quarter and 81 levels by Q3FY23.

Reducing Dollar Dependence

Even the recent move by the RBI to allow international trade settlement in rupees is seen as a move by the central bank to reduce India’s dependence on US dollars while executing trade. Over the longer term, as India trades in rupees internationally, it will curb the outflow of the dollar.

![]() “The latest RBI action will help in our trade with Russia, but one must understand that payment in rupees is not accepted by other regions such as UK, USA or the EU. This step helps make forex payments to Russia in rupees, which will help curb the outflow of the dollar," says Indo Count Industries’ CEO and Executive Director KK Lalpuria.

“The latest RBI action will help in our trade with Russia, but one must understand that payment in rupees is not accepted by other regions such as UK, USA or the EU. This step helps make forex payments to Russia in rupees, which will help curb the outflow of the dollar," says Indo Count Industries’ CEO and Executive Director KK Lalpuria.

Indo Count, a major home textile manufacturing company, exports to over 50 countries across five continents, majority of it to the United States.

India’ imports from Russia have jumped up 621 percent to $3.18 billion in April-May this year, according to data from the Department of Commerce. Russia formed 10 percent of India’s total crude oil imports.

Watching the psychological 80 mark and then the 85 mark to the dollar are important, but economists and trade experts will also watch how India’s trade deficit moves in coming months. Nandi of Nomura will be watching the current account deficit trend closely. "In June, India"s merchandise trade deficit rose to a record high ($26.18 billion), as export growth slowed but import growth remaining sticky and broad-based," he says.

Nomura estimates the current account deficit to widen to 3.3 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for FY23, compared to 1.2 percent of GDP for FY22. "This is where concerns on financing start to build in," Nandi says. Rising imports and widening trade deficits can risk hurting the country"s currency further in an environment of weak capital inflows.

For an export house like Indo Count, Lalpuria says the depreciation of the rupee would bring “momentary" benefit. This is because other currencies across Asia have also depreciated by nearly the same percentage, to the US dollar. “It brings us to a level-playing field and for some time it gives us the advantage of a depreciated rupee, because our quotations are in dollars and the realisations improve," Lalpuria adds.

![]()

Indo Count has hedged about 60-65 percent of its order book. Lalpuria says that fears of a recession in the US had grown “to some extent" in the current financial year, but inventory levels are getting reduced as the holiday season comes around in coming quarters. “Logistics are improving and so is demand. We may see an uptick in demand in Q3FY23."

The coming weeks, and possibly months, will test the decision-making abilities for companies like CynLr, Altigreen and Indo Count Industries. With the geo-political tensions yet to ease, all the attention will be on the US Federal Reserve to see when it might do a U-turn and start to cut interest rates on fears of a recession looming in the United States.

RBI in Battle Suit

RBI in Battle Suit The falling rupee has meant that India’s foreign exchange reserves have also been falling in recent weeks (see forex reserves chart), to $580.2 billion as on July 8, against $606.4 levels at the start of the financial year on April 1, according to RBI data. Economists say this is due to the fall in the foreign currency asset (FCA) levels.

The falling rupee has meant that India’s foreign exchange reserves have also been falling in recent weeks (see forex reserves chart), to $580.2 billion as on July 8, against $606.4 levels at the start of the financial year on April 1, according to RBI data. Economists say this is due to the fall in the foreign currency asset (FCA) levels. “The latest RBI action will help in our trade with Russia, but one must understand that payment in rupees is not accepted by other regions such as UK, USA or the EU. This step helps make forex payments to Russia in rupees, which will help curb the outflow of the dollar," says Indo Count Industries’ CEO and Executive Director KK Lalpuria.

“The latest RBI action will help in our trade with Russia, but one must understand that payment in rupees is not accepted by other regions such as UK, USA or the EU. This step helps make forex payments to Russia in rupees, which will help curb the outflow of the dollar," says Indo Count Industries’ CEO and Executive Director KK Lalpuria.