How climate change can impact GDP and jobs

Rising temperature, climate change risks, plastic pollution and high carbon emission not only impact lives and jobs, but also commodity prices, especially food. Is India prepared to commit more invest

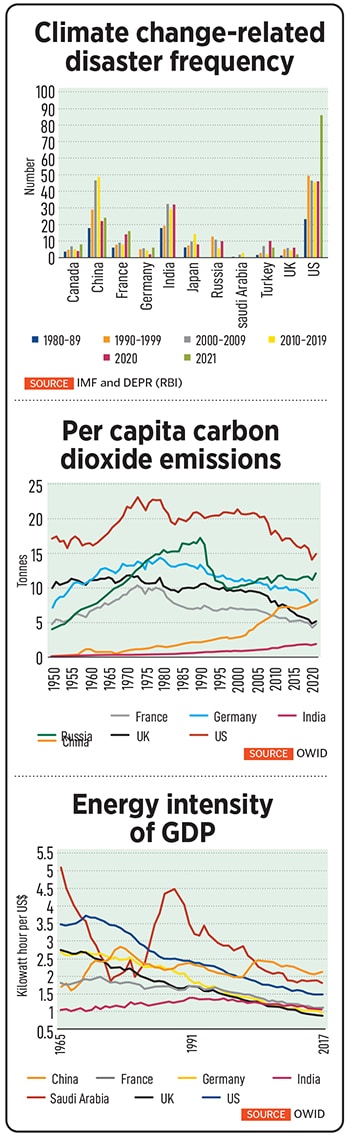

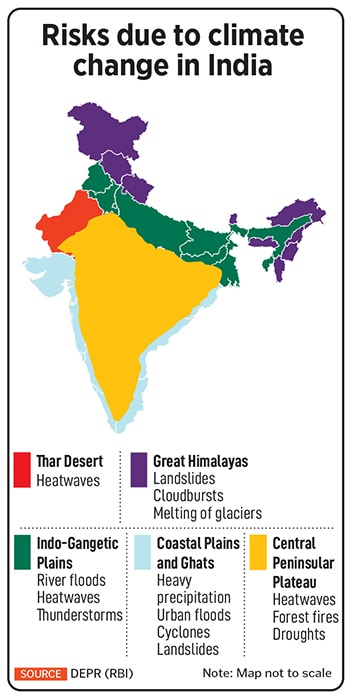

With change in climate threatening sustainability of life, livelihood and the ecosystem, economists and policymakers worldwide are sharpening their focus on mitigating such risks. However, it is a rather steep task, as India is among the top 10 economies in terms of vulnerability to climate risk events and is already suffering the adverse impact of climate change.

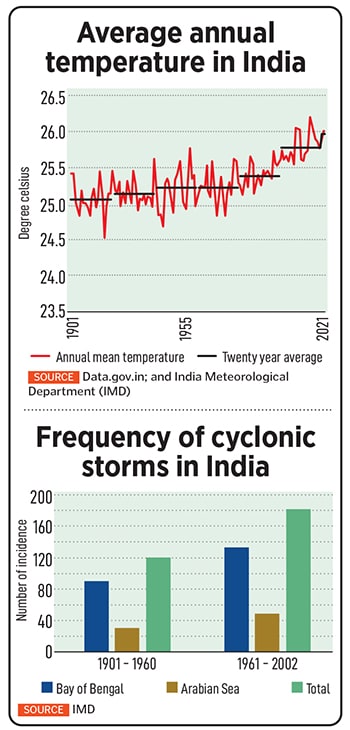

As India continues to face climate-related crisis like extreme heat temperature, scanty monsoon, floods and rising sea levels, the impact on overall macro and social environment is likely to be immense. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) estimates up to 4.5 percent of India’s GDP could be at risk by 2030, due to lost labour hours from extreme heat and humidity.

Climate change due to rising temperature and changing patterns of monsoon rainfall in India could cost the Indian economy 2.8 percent of its GDP and depress the living standards of nearly half of its population by 2050, RBI’s Department of Economic and Policy Research (DEPR) says in its latest report on Currency & Finance 2022-23. India may lose anywhere around 3 to 10 percent of its GDP annually by 2100 due to climate change in the absence of adequate mitigation policies.

The warning signs look scary. Indian agriculture (along with construction activity) as well as industry are particularly vulnerable to labour productivity losses caused by heat-related stresses. India may account for 34 million of the projected 80 million global job losses from heat stress associated productivity decline by 2030, according to World Bank estimates.

Statistics show India’s growing risk with dangers of rising global warming, higher carbon emission and plastic pollution. In 2019 alone, India lost nearly $69 billion due to climate-related events, which is in sharp contrast to $79.5 billion lost over 1998-2017. Floods in India during 2019 affected nearly 14 states causing displacement of around 1.8 million people and 1,800 deaths. Overall, around 12 million people were impacted by the intense rainfall during the monsoon season in 2019 with the economic loss estimated to be around $10 billion.

Statistics show India’s growing risk with dangers of rising global warming, higher carbon emission and plastic pollution. In 2019 alone, India lost nearly $69 billion due to climate-related events, which is in sharp contrast to $79.5 billion lost over 1998-2017. Floods in India during 2019 affected nearly 14 states causing displacement of around 1.8 million people and 1,800 deaths. Overall, around 12 million people were impacted by the intense rainfall during the monsoon season in 2019 with the economic loss estimated to be around $10 billion.

However, climate change is not an Indian phenomenon alone. According to the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO), the period 2015-22 is the warmest on record. Despite the cooling effects of La Nina into its third year, 2022 was the eighth consecutive year in which annual global temperature reached at least 1 degree Celsius above pre-Industrial Revolution levels, fuelled by ever-rising greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations and accumulated heat.

India faced its hottest February in 2023 since record-keeping began in 1901, according to India Meteorological Department (IMD) data. In March, large parts of the country experienced hailstorms and torrents of unseasonal rain, leading to apprehensions of extensive damage to standing crops.

“Preserving food and energy security amidst extreme climatic events while obtaining access to technology and critical raw materials required for successful green transition will, therefore, remain a key policy challenge for India," says Shaktikanta Das, governor, RBI.

With various policy approaches, like incentivising green financing, introducing green bonds and creating a market for carbon credits, the RBI and the financial sector regulators have increasingly focussed on risks to financial stability from climate change.

However, estimates suggest that annual green financing requirement could be about 2.5 percent of the GDP to address the infrastructure gap caused by climate events, which could increase if faster carbon emission reducing goal has to be pursued than what is committed under the NDC.

Nationally determined contributions or NDCs are at the heart of the Paris Agreement, embodying efforts by each country to reduce national emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change.

In line with the target of net zero carbon emissions by 2070, India’s NDC aims at raising the share of renewable energy and reducing the carbon emissions intensity of GDP by 2030. India presented its Long-Term Low Emission Development Strategy at the COP27, covering plans for the expansion of green hydrogen production, electrolyser manufacturing capacity and increased use of biofuels.

“The real challenge for India will be in arranging new investment, estimated to be in the range of $7.2 trillion (baseline scenario) to $12.1 trillion (accelerated scenario) till 2050," the RBI’s DEPR says.

India has seen a hike in food inflation as significant temporal rise, scanty and unseasonal rainfalls have caused crop damages leading to higher food inflation and its volatility.

Perishable vegetables like tomato, onion and potato (TOP) are more exposed to extreme weather events, such as cyclones and unseasonal rainfall during the post-monsoon period. Economists’ estimates show that usually it is the combination of TOP prices that move in tandem and price volatility in these three key items impact food inflation.

Perishable vegetables like tomato, onion and potato (TOP) are more exposed to extreme weather events, such as cyclones and unseasonal rainfall during the post-monsoon period. Economists’ estimates show that usually it is the combination of TOP prices that move in tandem and price volatility in these three key items impact food inflation.

Scanty rainfall has already had its impact on TOP prices so far in India. Prices of tomato jumped 233 percent from Rs33 per kg in June to Rs110 per kg in July. Compared to last July, tomato prices rose by 200 percent. As per the department of consumer affairs data, the average retail price of tomato in June was at Rs32.6 per kg, whereas wholesale price was at Rs24.9 per kg. Similarly, prices of potato and onion, which are key in Indian cooking, also surged 16 percent and 9 percent, respectively, in July from a month earlier. Chilli cost 69 percent more in July while cumin prices also rose by 16 percent.

However, these are not exceptional rise in TOP prices. Inflation in onion prices shot up to 327 percent in December 2019 led by unseasonal rains potato prices by 107 percent in November 2020 due to unseasonal rains and tomato prices by 158 percent in June 2022 due to heatwave and cyclone.

According to economists at Nomura, the rise in commodity prices, especially in food prices, is worldwide and mostly driven by supply issues and not demand. A supply-driven surge in commodity prices can have more serious stagflationary consequences, for not only does it add to retail inflation but also weakens growth, as, in the absence of strengthening demand, dearer food and energy erodes household purchasing power and corporate profits, explains Nomura.

“The single-most important factor has been extreme heatwaves around the world—the average global temperature made July the hottest month on record—that is hampering agricultural production. Meteorologists are warning of a severe El Nià±o event, as central and eastern Pacific sea surface temperatures are exceeding El Nià±o thresholds, and their international climate model forecasts indicate further warming is likely until at least the end of the year," says Nomura.

India is a net exporter of food, but it remains vulnerable to spillover effects from higher global food prices and is exposed to rising oil prices, since it imports more than 80 percent of its crude oil needs.

Indian companies are gearing up to face climate risks but are not there yet. According to Deloitte India’s ESG preparedness survey, merely 27 percent Indian organisations feel adequately equipped to meet their environmental social corporate governance (ESG) strategy and compliance requirements as it reveals a significant gap in preparedness and action.

The survey conducted by Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu India LLP (Deloitte India) was rolled out to 150 organisations (with over 70 percent of them listed in Indian stock exchange) to assess their readiness for ESG requirements (policies, regulations, disclosures, and compliances) and evaluate their ESG strategies and efforts. Over 70 percent of these organisations are also listed on the Indian stock exchanges.

The survey conducted by Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu India LLP (Deloitte India) was rolled out to 150 organisations (with over 70 percent of them listed in Indian stock exchange) to assess their readiness for ESG requirements (policies, regulations, disclosures, and compliances) and evaluate their ESG strategies and efforts. Over 70 percent of these organisations are also listed on the Indian stock exchanges.

“Organisations are grappling with evolving expectations on ESG compliance and disclosure from investors, boards, governments, and consumers. They need to account for emerging global regulations on sustainable finance, climate disclosures, biodiversity, and social and governance dimensions, including gender diversity and living wages, within a couple of years," says Viral Thakker, partner and sustainability leader, Deloitte India.

From a sector-specific perspective, consumer industry was found to lag, with only 7 percent organisations indicating robust preparedness for ESG requirements. Nearly 80 percent organisations in the energy, resources, and industrials (ER&I), financial services, and life sciences and health care industries (LSHC) were categorised as either well-prepared or moderately prepared to meet ESG requirements.

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the world utilises approximately 450 million metric tonnes of plastic a year, approximately 57 kg per person. Each year, more than 350 million metric tonnes of plastic become plastic waste, of which approximately 80 million metric tonnes become mismanaged plastic waste, also termed plastic pollution.

“This plastic pollution is estimated to come at a significant social and environmental cost—at least $300 billion per annum, and, according to certain estimates, as high as 41,500 billion per annum," says Credit Suisse research institute.

It adds that, over the past 60 years, the plastic usage intensity of GDP has dominated both the growth in population and GDP per capita. For every dollar of GDP added to the global economy, the data suggest that an increasing amount of plastic was required. With the highest population, both India and China account for a significant portion of mismanaged plastic waste. “Of the current 80 million metric tonnes of annual mismanaged plastic waste, almost 90 percent originates from non-OECD countries, with China and India contributing 22 percent and 11 percent to the global total, respectively," says Credit Suisse research institute.

It believes the negotiations for a global plastics treaty initiated by the United Nations Environment Assembly have the potential to be the most significant sustainability-focussed multilateral proposal since the Paris Agreement in 2015.

First Published: Aug 22, 2023, 13:34

Subscribe Now